Swell Maps, Eric’s, 1978

It may seem an indulgence to dedicate a whole book to the bricks and mortar of a music venue. But the 2i’s coffee bar, The Cavern, CBGB’s, Studio 54, The Marquee, The Roxy, Haçienda et al are as intrinsic to the weave of rock and pop history as the artists and DJs who played there. Does Liverpool’s fabled punk-era haunt merit inclusion in such company? And does it require such a monumental literary undertaking (500 densely packed A4 pages)? If reading it is intimidating, Lord only knows how author Jaki Florek negotiated the task of compiling it. But the extraordinary length does allow her to thoroughly chronicle the musical forces at play in Liverpool from the mid-70s onwards, with Eric’s at the centre of a rapidly expanding and colourfully populated universe.

Liverpool Eric’s . . . is essentially a folk history, an eyewitness account in which first-hand testimony is collated without undue contextual weighting. And while that’s the one obvious critical qualm, the sprawl of opinion and fact is also the joy of the enterprise. Before we get anywhere near the core of the story there are backward glances to Merseybeat and that even more fabled Liverpudlian amphitheatre, The Cavern (similarly sited in Matthew Street). The narrative feel is that of a scrapbook, taking detours into pertinent historical interviews (amid new ones) alongside diary entries from key players. And the illustration, which includes a treasure trove of fresh photographic discoveries, is wonderfully evocative of time and place.

It’s amusing to note (not least because I’m simultaneously reading John Robb’s oral history of t’other place, Manchester) just how deeply entrenched the connections and rivalries are between the north-west’s two major municipalities. And how contested their abundant claims to primacy remain. You have to love the fact that Liverpool’s most important contemporary music venue was given a name so prosaically Anglo-Saxon, familiar and downbeat. Manchester’s Haçienda boasted a name that reeked of European classicism (the wholly superfluous addition of a cedilla notwithstanding). A little grain of truth about the aesthetic separation between the cities lies in there somewhere.

Both books sample one of the few extant interviews with Roger Eagle, arguably the most pivotal non-artist enabler in the post-Beatles musical trajectories of both cities. Eagle’s contribution gets thorough but proportionate recognition here. He was fundamental in turning both cities into hubs for black R&B and soul, notably as DJ at famed Mancunian venue The Twisted Wheel. Galvanising others into action with missionary zeal, he acquired the finest imports and familiarised the respective populaces with the great American R&B songbook. Later he would promote rock bands at The Liverpool Stadium, a fleapit nominally housing boxing and wrestling events, alongside first lieutenant Doreen Allen, who would follow him to Eric’s. He is credited with being the first prophet of Northern Soul but, as revealed here, was ambivalent about its regimentation of style. When punk arrived, his enthusiasm was rekindled and he waded in knee deep, a train of apostles in his wake. Among the interviewees are Eagle’s co-conspirators Pete Fulwell and Ken Testi, who helped found Eric’s. Another is Geoff Davies, who had a vinyl habit to rival Eagle’s, and whose Probe Records became the epicentre for Liverpool’s music community from the 70s onwards, later birthing the city’s pre-eminent post-punk/indie record label.

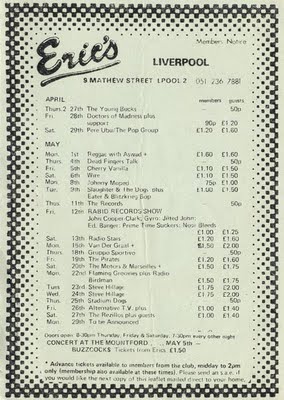

A typically impressive gig list

It’s only by chapter seven that the focus narrows to Eric’s the club and the first gig it hosted (The Stranglers 1-10-76). They were “nice lads” despite the PA flaking out. The Runaways were booked sans contract in the hope they wouldn’t pull out when they discovered this deliberate oversight (Eagle didn’t fancy putting his hand in his pocket to help with the promotion). The Pistols were “horrible” and “broke lots and lots of glasses”. £5 in takings, £30 in damages. The cream of the punk generation graced the venue. The Clash gig when Pete Wylie bumped into Julian Cope – and said meet my friend Mr McCulloch – boasts a mythology akin to the Pistols’ first Lesser Free Trade Hall show. But Eric’s was never ‘just’ a punk club – Eagle continued to book a Wednesday night jazz session as well as reggae acts. Paying customers were thin on the ground for both but Eagle was never unduly swayed by monetary concerns.

Yet he knew how youth movements worked and observed that if you “get the gays and the hairdressers, the rest will follow”. Which is where Jayne Casey, receptionist at A Cut Above The Rest, enters the fray. Liverpool punk’s It Girl is to her adopted city what Linder is to Manchester – a natural creative who managed to balance being the definition of cool with pretty much universal affection. On her coat-tails came Pete Burns, Holly Johnson and others. A door policy that encouraged this clientele’s self-expressive instincts procured a very singular cast of regulars, with none of the undertones of violence and threat that attended gigs at London’s Roxy (though the gents toilets are reported as being even more repulsive).

The cast ultimately incorporated the proponents of a new stripe of Merseybeat entirely. Ian McCulloch (whom Doreen would have to walk to the bus because he wouldn’t wear his glasses in public and couldn’t make out the route numbers), Julian Cope and Pete Wylie were all part of the Eric’s generation. There is a monster interview with the latter (the authors’ admission that she had to compress 115 pages of transcription and notes into a mere 16 pages gives indication of Wylie’s renowned loquacity). There’s also a comprehensive history of Zoo Records, whose stature mirrored Factory until Bill Drummond ran out of money, and launched the careers of the Bunnymen and Teardrop Explodes (Wylie’s Wah! came to light on Fulwell’s Inevitable imprint). And Drummond himself, of course.

The story concludes with a chapter on the closure of the venue due to police pressure. Richard Butler of The Psychedelic Furs, the last group to grace the stage, nonchalantly recalls being planted with drugs as uniformed killjoys arrived mob-handed. Marches and press campaigns were unable to persuade the civic authorities that they were losing a vital piece of Liverpool’s culture.

Yes, there’s too much here that isn’t subject-specific and could have been lost in the edit. But that’s the sole criticism. A phenomenal undertaking.