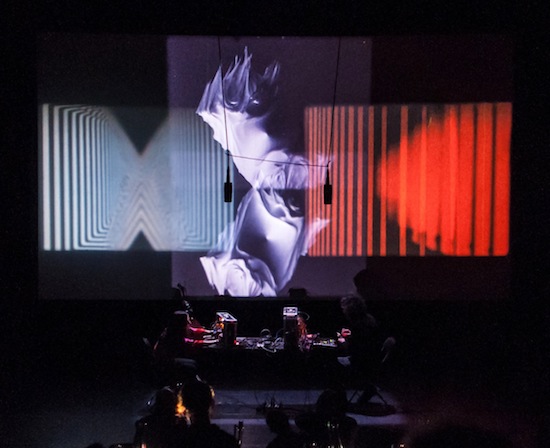

Live photograph by James Welburn

On a black canvas streaks of light travel as if they are reflections cast by movements beyond the field of vision. They smoothly divide, diffract and distort, forming purposefully surging patterns that invoke cyclically morphing objects in solid, liquid and vaporous phases. The occult choreography is highly repetitive, yet hides its seams, underscored by a thick, low end synth worm rhythmically writhing in electrical discharge. The combined effect unfurls to envelop its audience. Oh, and there’s red, lots of red.

Such first impressions of Rose Kallal’s audio-visual art confuses one’s sensibilities, coming across like both an extra-terrestrial intelligence reaching out and a hypnotic ritual heading within to mine the psyche. Although wary of drawing firm inferences from such an abstract display it was unsurprising to learn that science fiction and astrology were within the New York-based artist’s sphere of influences, as we discussed her unique, visionary work before her performance at London’s Café Oto in April.

Rose Kallal: I grew up in the seventies, so I’ll always love science fiction. I think when I was ten years old Soylent Green [the 1973 post-apocalyptic thriller] was my favourite film. I love dystopian science fiction, its vision of the future – the dream, this yearning for some better time.

Some of your films remind me of the ‘star gate’ sequence towards the end of 2001: A Space Odyssey. Back then, they had to actually create the light and patterns, whereas today’s CGI makes everything slick and smooth.

RK: Yeah, I like materiality a lot. I prefer analog – older processes are just more tangible than purely digital stuff. I mix different mediums, different technologies, and I think film acts as a filter where it unifies the different elements and makes it one. But, obviously, it’s interesting looking at early, older technologies, early computer animation and stuff like that.

That fits with your mix of technologies [16mm film, analogue video synthesis/feedback and computer animation with modular synth soundtracks]. What came first, working with images or sound?

RK: I went to art school in the eighties. I got in [to OCAD University, Toronto] with painting, but then took film, video and photography. I then did one year of art school in New York in the late eighties – they didn’t have film equipment, so I focussed on still photography. I wanted to stay in New York at that time, but had some immigration issues, ’cause I’m Canadian, so I had to be back in Toronto. I was exhibiting photo-based work at that point, [although] I never really thought of myself as a photographer. I was always interested in the relationship between the macroscopic and microscopic. One exhibition I did was triptychs; the relationship of the images [when] knitted together, the changing of their context, how images work together, interested me back then.

But when you’re exhibiting you maybe have an exhibition once every year and I wanted something more immediate, so I started learning and playing music. I started [with] guitar and drums and then I bought my first synth in the mid-nineties. I was in bands and it was very improvisational – I’m not innately a song writer or anything like that, so I naturally started getting into soundtracks.

In the late nineties I started shooting film again – I joined a film co-op – that was when I first merged my sound work with my visual work. I made a short film [Flow] and for the soundtrack I used Wurlitzer piano, synth and guitar – it sounded fairly electronic. [That was] the context in which I wanted to make music and merge my visual work and the sound work.

I moved back to New York in 2002 and connected with the art world there – I’ve never really pursued the film world, it’s more the music world or art world. I was DJing at Gavin Brown’s Passerby [the much-loved bar that was connected to Brown’s gallery in Manhattan]; he had this performance space in the back room and I started doing live performance there. I think 2006 was the first time [I performed] with my current format of [projected] film loops with live sound. There’s a real magic with projected film. Some of my short films were shot on film and transferred to video, but I always thought they lost something; and it’s harder to do multiple video screens [whereas] I [like to] do stuff with four projectors.

Your work with multiple projectors presumably creates some unpredictable elements where they overlap, and with analogue synths there’s also the same…

RK: …unpredictability – yeah. I’m also interested in nonlinear systems, like the loop or even video feedback, and elemental processes.

I view consciousness, or reality, as very cyclical in nature and it relates to astrology. I use repetitive motifs, they’re run at different speeds or different lengths, so you get these magical moments where you’ve got a symmetrical pattern that goes out of phase.

Has your focus on film loops with live sound meant you’ve migrated from art spaces to gig venues?

RK: I like both. I had an exhibition two years ago and I show with a gallery in New York, so I do really like installation, but I really enjoy performance compared to the art world. I think what I do is very experiential, so I like the focus [with live performance] where people sit for half an hour and experience something, as opposed to galleries where you can go in and out, you can be distracted.

When I did my exhibition two summers ago, for the opening I had reel-to-reels and four film loops and tape loops hanging from the ceiling and, because there weren’t any gallery monitors, I had eight twelve-inch speakers, a five foot Sunn PA kind of thing [laughs] and people said it had the feel of a live performance. It’s a cool space – I do like basement -type spaces [laughs], I like the subterranean, I think it relates to subconscious…

Specific imagery crops up again and again in your films, like light, liquid and vapours – what makes you return to specific images?

RK: I think they’re elemental. My video feedback has this watery, fluid quality. I’m always searching for new ways to express these elemental things.

On the sound side there are also consistent motifs coming across – the predominant low end synth textures you use that morph around – are you aiming for a physicality of sound?

Definitely. I think it’s my interest in the experiential quality of the sound. I’ve been playing modular synths since 2009. Robert Aiki Lowe, he’s a good friend of mine, he was very influential, and when I saw Keith Fullerton play that was pivotal, his sound was amazing.

‘Emerald Vision’ Multiple 16mm film loop installation by Rose Kallal. Modular synth soundtrack by Rose Kallal with Mark Pilkington.

I’d heard you were a practiced astrologer.

RK: Mm no – I’ve been interested in it, and I follow it, but I don’t do it. I’ll do it for friends, but I don’t normally give people readings. A good friend of mine since the late eighties, she’s a proper astrologer, so it’s through her that I bought an ephemeris [astronomical almanac] and followed my chart. It’s more of a personal thing: just your close acquaintances; you catalogue it over maybe twenty years – what happens in a person’s life when Saturn’s in conjunction with their ascendant – you begin to see the cycle. To me it’s just like the weather, it’s not so much predictive, it’s natural cycles. Looking back over many years there are cycles of expansion and contraction and you kind of flow with it a bit more, it’s like “it’s winter time now and that’s alright, it’s not supposed to be spring” you know?

How does it influence your sound and visuals?

RK: It’s just, again, my interest in the cyclical, how I view things in a more cyclical way, I think you’re innately attracted to these things.

You can experience more of Rose Kallal’s visual and sound art here