Just a couple of weeks before Modern Life Is Rubbish was released on 10th May 1993, British Prime Minister John Major delivered a speech. It was St. George’s Day, and his address was intended to rally the Conservative Group For Europe. In it, he extolled the virtues of economic cooperation with the continent, but insisted that this didn’t have to come at the expense of British identity. "Fifty years from now Britain will still be the country of long shadows on county grounds, warm beer, invincible green suburbs, dog lovers and pools fillers and – as George Orwell said – ‘old maids bicycling to Holy Communion through the morning mist’… Britain will survive unamendable in all essentials." It’s curious, isn’t it, that a speech by a Conservative prime minister now in 2018 strikes a not dissimilar tone to a record by a leading indie pop group of the time. New Labour’s Cool Britannia was never as far from Major’s vision of England as its architects might have liked to think, just as Modern Life Is Rubbish set the tone for the jingoism of Britpop.

Back in the days when there was coin around in the indie music industry, bands were able to do interesting things in a quest to keep faltering careers alive. Blur’s Starshaped documentary, made in the years between debut album Leisure and Modern Life Is Rubbish is one such artefact. It’s a frequently charming work, capturing the trials and tribulations of a moderate sized indie band stuck in a van doing the rounds of gigs, festivals and John Peel. Graham Coxon gets hammered and says rather less than charming things about PJ Harvey’s songs being about her "monthlies". Alex James demurely drinks tea from a cup and saucer on the back seat while looking indecently pretty. A Doc Marten boot wearing Damon is all wide-eyed and Tiggerish. Dave is Dave. Starshaped captures Blur at a curious time. Leisure had been a commercial success that sold 200,000 copies in just four months but had failed to do the expected and crack America. The ‘Popscene’ single had flopped and it seemed as if everyone had moved on from Blur’s curiously opportunistic mixture of baggy and shoegaze. Meanwhile, in a flap of terylene shirts, slapped arses and dramatic songs about suburban shagging, Suede had rudely flounced onto the scene to steal Blur’s thunder.

I had expected this feature to be a revisiting of a fondly-remembered album that I had always considered to be Blur’s best. It was a surprise, then, to hit play for the first time in a long while and find myself more than a little irritated. To my adult ears, knowing what Blur and the 1990s would become, there’s something grasping about this record. Nobody is immune to nostalgia and I can listen to it and mouth along with the words. I still know them off by heart. Hearing it I am instantly transported back to my parents living room in the summer of my GCSEs, flicking between this and and Radiohead’s The Bends, not really working, watching the light come through the windows and feeling fucking thankful that the first hellish five years of secondary school were finally over. Do I want to go back there? Of course not. It is the past, the me that was present then is dead. Who wants to live in their childish memory?

It seems many do. As Albarn sang on the rather beautifully languid ‘Blue Jeans’, “I don’t really want to change a thing / I want to stay this way / forever”. The 1990s was arguably the most backward looking decade in history perhaps because, as we were told, history was over. This malaise has stuck with us. My generation, the weird hinterland between Generation X and the Millennials, still keep far lesser bands than Blur celebrated and fed. If you fancy a truly terrible day out this summer, why not head to the Cool Britannia Fest at Knebworth, featuring something called Britpop Classical. Modern Life Is Rubbish, as the opening salvo in Blur’s Britpop trilogy, is steeped in this nostalgia. There was a double meaning to the choice of title – as Damon Albarn told NME at the time of its release, he believed that there was nothing new to say: "Modern life is the rubbish of the past. We all live on the rubbish: it dictates our thoughts. And because it’s all built up over such a long time, there’s no necessity for originality anymore. There are so many old things to splice together in infinite permutations that there is absolutely no need to create anything new." How depressing. In this, he and Modern Life Is Rubbish set the template for Britpop.

Cosy artifice and complacency was part of the DNA even on this, Blur’s most consistent and enjoyable album. Now there’s a paradox. I had thought it was an innocent record made before Damon Albarn learned the art of sniffing the wind to jump on whatever cultural shift was about to hit the mainstream, such as when years later as Britpop imploded later he announced that Blur suddenly "got America" and they started sounding like Pavement. But then you go back over the music press archive and realise that even then, he had that knack. In 1993 Albarn recalled how he’d gone to the band’s record label Food and said "’in six months time, you’re going to be signing bands who sound English, because that’s what everyone wants’. They were very skeptical, but we persevered. And it seems to have worked". He was displaying these calculating, magpie tendencies as far back as 1991: "When we started, the Blur experience was always quite kitsch… it was more of a head thing, an idea that we can do this because we are cleverer than everyone," he said, "but now I’ve realised there were a lot of people who were very clever before me, and they produced good music as well. Blur have always been a concept, they’ll never be anything else, but all the best things are concepts." There’s a weary cynicism to this, an approach that curiously sits with so much of 90s culture, from the YBAs to that football programme with the two blokes on a sofa. Where’s the guts, the soul? What was it in the water that made so many artists born in the late 60s and their fans of the late 70s so complacent? He added that his ambition was that the band become "a Thing… the Thing is very important in my vocabulary". How very New Labour, that nothing matters except the quest for power, prestige, prominence. As Damon sings on ‘Colin Zeal’, "he’s pleased with himself / so pleased with himself". Quite.

In interviews from the time, Damon claimed that he hadn’t listened to music for years. In March 1992 he told Stuart Maconie that his new girlfriend (presumably Justine Frischmann) had a huge record collection that he started to plough his way through. "I began to see all these little coincidences where we were linked with bands that we worshipped," he said, "and I began to realise that, fuck, we are something. We are part of a heritage of British bands. We are somebody." Or rather, in mining that heritage Blur became somebody made up of bits and pieces of that heritage – The Small Faces, The Kinks, XTC, Julian Cope, The Cardiacs, or on ‘Coping’ the same sort of early Wire pastiche that’d later be perfected with brutal efficiency by Frischmann’s Elastica.

Despite all this, I am not trying to say that Modern Life Is Rubbish is a bad album. Much of the songwriting is great and it doesn’t suffer from the risible kneesupmuvvabraaahn numbers that blight the inconsistent Parklife and Great Escape. There’s a sense of a band working out exactly what it wants to be, which is always a fairly thrilling thing to listen to. ‘Chemical World’, ‘Colin Zeal’, ‘Miss America’ – all of these melodies stand the test of time, which is why they’ve stuck with me. But listening now, however familiar and hummable they are, there’s something amiss, it grates, infuriates.

Partly this is because the sonics are all over the place. There’s a distinctive sound to this record, but oftentimes it’s a very soupy one. If the artists that the album is referencing were known for a lightness of touch, Modern Life blends them to a bit of a soup supporting Albarn’s affected Estuarine vocals. I wonder if with a lighter production and less of a blatant desperation to stamp their place on what was coalescing as Britpop this would be a record that I could enjoy with adult ears and not just the memory of my former self. These are really wonderful songs yet mostly now sound curiously flat. What was it Damon Albarn said in March 1992, a year before Modern Life Is Rubbish was released? Ah yes: "Not that there’s anything wrong with being bland. I’m into that."

The best bits? The aforementioned ‘Blue Jeans’, the summery insouciance of ‘Starshaped’, the heady ‘Oily Water’ or ‘Pressure On Julian’. That song sounds drunk, swirling and giddy after too many in the sun, Albarn’s lyrics their most vivid on the record, a nightmarish vision "Swimming in yellow pissy water / Sand getting in between their ears / No blood in head in this bloody weather / Irate people with yellow tonges".

But it’s in the lyrics that the problem lies. It’s just so hard to inhabit the lives in these songs, the "unconscious man" in ‘Starshaped’ who "has a couple at the weekend / keeps up the cameraderie" and washes "with new soap behind the collar / Keeps a clean mental state". Or on Sunday the bloke who "gathers the family round the table to eat enough to sleep". Colin Zeal’ is a far more interesting character portrayal than the cartoons that came later, but across Modern Life you can hear the Blur Blokes starting to develop. They’re always more Martin Amis than the darker, more complex figures of, say, Patrick Hamilton.

New bars of soap, sugary tea, bingo, peeping toms, an old soldier in the park who "fought for us in two world wars, and the England he knew is now no more": Modern Life Is Rubbish has a vision of nationhood a hair’s breadth from that John Major speech. While the pea enthusiast PM had his long shadows on the village green, Albarn on that US tour had missed "queuing up in shops… people saying goodnight on the BBC… really simple things," he told the NME in 1993. The result? "I missed everything about England so I started writing songs which created an English atmosphere". The album has its roots in rose-tinted views of home, the musical equivalent of some expat Brit ordering copies of the Guardian to be read days after their street date as he sups sadly on a can of Boddingtons, buttering toast for Marmite posted over in a care package from his auntie. From the hokey Englishness that they began to explore on Modern Life Is Rubbish there’s a direct line to the muddled Albion thinking of The Libertines. They share the same ‘umpty dumpty coconut shy jollity – you might ride Blur’s daft end of the pier organ interludes to The Libertines’ boutique Margate hotel and their ‘Tiddeley Om Pom Pom Tour’. I know how powerful this instinct is because I felt it myself. A decade ago I spent a summer in the middle of the United States and, in the booze drought, freeways and grim malls of Denver Colorado was surprised to find myself enjoying the parochial sounds of Tthe Libertines and revisiting largely-forgotten Blur records on my Minidisc player. It ended as soon as the 747 touched the tarmac of Heathrow, but I’ve subsequently found it interesting how a simplistic fondness for the homeland was triggered by the nostalgia that comes with absence.

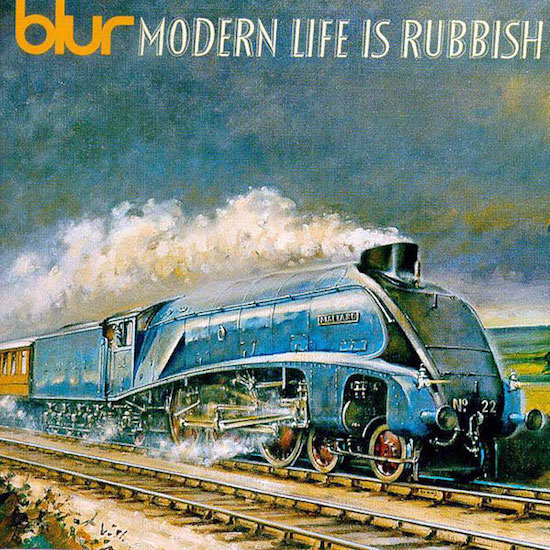

The less-than-subtle evocations of Englishness didn’t just come in Albarn’s auditioning-for-Dad’s-Army lyricism ("it’s been a hell of a do" and so on) but in the cover artwork and the pictures of Spitfires on the inner sleeve. Now, I find the Class A4 locomotive, designed for the LNER by Sir Nigel Gresley in 1935 to be one of the most perfect meetings of form and function in design history, that sleek and streamlined shape, the way that the lines of the locomotive arc up over the wheels like the crest of the wave or curve of a bird’s wing. Engine number 4468, The Mallard, still holds the world speed record for steam locomotives. There she is on the cover, blasting up the mainline with smoke streaming back from her funnel. The Spitfire too is a design classic. Yet their use on this record contains no ambiguity, no questioning but a statement, a deliberate tug on nostalgic sensibilities that, to modern eyes, belongs on a Nigel Farage’s lavatory wall, not a pop record. Blur weren’t to know that at the time, of course, and neither did John Major know that his European dream would end up being destroyed by a man who used just the same nostalgic evocations as in his 1993 speech. English identity is a Pandora’s box that once unleashed has a dangerous power. In pop and politics alike, the retromania of the 90s was part of the first stirrings of the little Englander mentality that has poisoned our cultural life since.

If you are going to explore identity, it has to be done with care and a critique. Much of the problem Modern Life Is Rubbish is that however pleasant sounding these English vignettes are, there’s very little grit to them. Albarn’s characters never seem to explore our nation’s sickness and faults. At the same time as Blur put this out, Suede and Pulp were writing music that dealt with class and the sticky underside of British working and lower middle class life. Blur sang of the comforts of “sugary tea” on ‘For Tomorrow’. Suede were shitting paracetamol on escalators, a band driven by lust, love and ambiguity who were about to work with Derek Jarman. Pulp were embracing electronic music, imagining the concrete of Sheffield quaking with hot summer carnality, on the way to becoming a band who saw sex as a weapon in class war. For all Oasis’ Beatles and potatoes classicism, their lyrical energies were all about aspiration and a better life, even if it was to be built on white powdery foundations. There’s precious little of that here, and Blur’s cynicism enabled them to end up going down the easy route of cliché and chips that was Parklife, taking Britpop in its dreary, Cool Britannia direction. As Jarvis Cocker had it in the greatest pop single of the era, "everybody hates a tourist / especially when they think it’s all such a laugh". There was nothing in the Modern Life template that the beery heteroboys who would come to ruin British guitar music in the 90s would find threatening. As Stephen Dalton wrote in a March 1992 Vox article: "Blur’s blandness is far more interesting: the sort designed to last, spiky on the outside but sensible within." But who wants that? Unfortunately, people clearly did.

In the sleeve to the record, ‘Sunday Sunday’ came with a subtitle borrowed from the neologism "legislated nostalgia", coined by Douglas Copeland in his 1991 novel Generation X and defined as "to force a body of people to have memories they do not actually possess." It’s a telling line that illuminates the impact that the 1990s have had since, and one that is only now, with younger generations who’ve grown up with everything all at once, are starting to undermine. In that, Blur now sound curiously anachronistic. Perhaps a desire to put clear water between themselves and what must have been a bizarre old time is what has inspired Graham Coxon to release excellent solo records in his own right. Damon Albarn has subsequently put a good fist of pushing himself in more experimental directions, even if the results have not been to my taste. Let us not waste a further thought on Mr James, cheesemonger to Clarkson.

As it was, Modern Life Is Rubbish set the template for the rest of Blur’s Britpop 90s. Setting fire to the subtlety that still existed across this album, they mastered cartoonish pop songs that crushed the charts. In doing so, their records became frustratingly inconsistent – indeed, for a while Blur were one of those bands you can’t trust because their best songs are the ballads. The rowdy songs are just flatter rehashes of the better rowdy songs on Modern Life. On Parklife the wonders of ‘To The End’, ‘This Is A Low’ and ‘Badhead’ are let down by the risible and cartoonish ‘Tracy Jacks’, ‘Bank Holiday’ and, of course, the title track. The Great Escape fares even worse, an entire record of Britpop over-indulgence carried by the sublime ‘The Universal’ and ‘Best Days’. Indeed, it’s interesting to listen to Modern Life and notice that Blur essentially wrote the same track three times – as ‘Sunday Sunday’, ‘Parklife’ and ‘Country House’, all of them cheery pop stompers populated characters as two dimensional as the songs themselves. Their mid-90s were defined by a split-personality that would see increasing rifts between the always more esoterically-inclined Coxon and the rest of the group. Modern Life Is Rubbish and its callow mining of cynicism and nostalgia makes it the most of its time, the ‘most 90s’ record of Britpop. It ended up making them a lot of money, sure, but it’s also curious sound of four bright-eyed pretty boys with some fair musical chops about to become charmless men, writing the soundtrack of an increasingly charmless land.