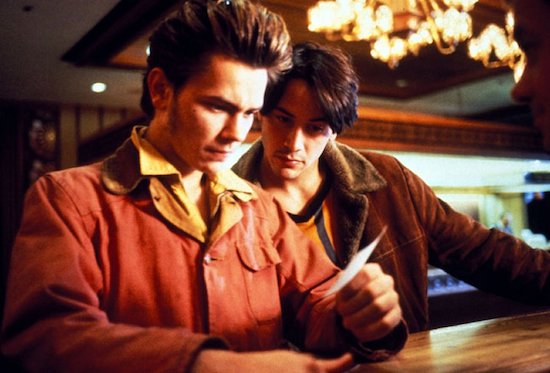

I became aware of My Own Private Idaho, the year of Phoenix’ death, two years after the film’s release. Secretly reading my sister’s Just Seventeen magazines, I was enamoured by the film’s poster boys, River Phoenix and Keanu Reeves, sprawled all over its pages on a regular basis. It was specifically an obituary feature on Phoenix which highlighted all his roles and predictably the gay-themed My Own Private Idaho caught my eye, the budding gay boy that I was just hitting puberty.

Not long after, I managed to get my hands on a pirated VHS version and of course was majorly aroused by the pivotal sex scene, a three-way between Mike (Phoenix), Scott (Reeves) and Hans (Udo Kier), a cabaret artist who hires the boys for the night, where director Gus van Sant presents it in moments of stasis. I had so longed for some flash of genitalia – or at least some gyrating movement – to make the scene look less staged.

Unbeknownst to early teens me, the film was the flag bearer of a series of independent gay-themed films in a movement called ‘New Queer Cinema’, a term coined by journalist B. Ruby Rich in a 1992 article in Sight and Sound. These films were predominantly released from the mid to late 80s through to the early 90s and were seen to draw from the postmodernist and poststructuralist academic theories of the 1980s, presenting human identity and sexuality as socially constructed, more fluid and interchangeable. It was also widely understood that the genre may have echoed the current accelerated cultural and political evolution of gay identity brought on by the challenges of the AIDS crisis.

The genre featured a series of well-known films and upcoming directors including Tom Kalin’s gay murder mystery Swoon; the monumental Jennie Livingston documentary Paris is Burning, chronicling New York’s ball culture and fringe communities; Todd Haynes with his gay debut Poison; Greg Araki’s HIV road movie comedy The Living End; and the already established experimental English filmmaker Derek Jarman with his film Edward II. Their films were radical, seeking to challenge assumptions about identity, gender, class, family, and society – whether it be heterosexual or homosexual.

Made on a budget of two-and-a-half million dollars (having grossed 6,400,000 since), My Own Private Idaho had a lo-fi yet stylised quality that was to become Van Sant’s trademark, but also the staple of the genre. The aesthetics and attitude, covered a range of imperfect cinema from low budget hand-held cameras to sophisticated black and white composition, usually with small casts and minimal locations, narratively highlighting the lives of LGBTQ+ protagonists living on the fringe of society, such as the kids and hustlers living on the squalor streets of Portland, where My Own Private Idaho is set.

Phoenix received great praise for his role and rightly so. Full of promise and charisma, his dishevelled, drug-addicted-yet-loveable lost soul was a truly exceptional and natural performance. The role was a personal statement, which mirrored some elements of his own personal struggles at the time. Reeves on the other hand, gives his soon-to-be-signature wooden performance. His stilted dialogue delivery proved comedic at points but somehow worked with the film’s theatrical undercurrent.

Like many of New Queer Cinema attributes, the film intermingles narrative with political and artistic expression. Shakespearian rhyming stanzas fuse with grungy Pacific Northwest hustler vibes; scenes where medieval style gangs of thieves secretly gather to plot their next attack is contrasted with documentary-style interviews of gay prostitutes in Seattle cafes, chatting about turning tricks. The film is interjected with montages of visual metaphors, old wooden houses crashing down from the sky, salmon fishing upstream, even those quasi-stop-motion sex scenes which I found so tantalizingly frustrating were stylized in the look of a porn magazine photo shoot. Then, in other scenes, the cover boys of such magazines, laid out on a newsstand, come to life and speak directly to the camera.

Sexuality is presented as a chaotic and subversive force, which is alienating and likely to be repressed by the dominant heterosexual power structures. Mike makes his living out of hustling, which casts a shadow over his sexuality; he sleeps with both men and women. Van Sant never fully discloses but one assumes Mike is gay from the more obvious moments, such as revealing his love to Scott or becoming jealous at Scott’s new girlfriend. However, he does spend a lot of the film high or collapsing (he suffers from narcolepsy) or paralysed by his convulsions, giving an unclear picture of his sexual leanings.

Within Scott there is also ambiguity. In the moment when Mike discloses his love to him, Scott rejects him, declaring that he only sleeps with men for money. It’s hard to believe that Scott resorts to hustling as the eldest son of a very affluent family. Is hustling the only way he can rebel against the overbearing patriarchy of his home? Could it be that there was already some degree of homosexual desire within him? It would explain his daddy obsession with the Dickens styled character Bob Pigeon (William Richert), a sort of middle-aged mentor to the gang of Portland street kids and hustlers.

The genre was overall short-lived as gay-themed films started to slowly creep into conventional Hollywood consciousness. It was only a year later that I was old enough to see the Tom Hanks starring, heteronormative AIDs drama Philadelphia, made on a budget thirteen times bigger than My Own Private Idaho. Other major releases throughout the decade soon followed: the Wachowskis’ Bound, The Opposite of Sex, Boys Don’t Cry, to name a few.

In comparison to recent gay filmic outputs, one could say that My Own Private Idaho, holds itself back. Remaining just as effervescent and poignant to this day, its perhaps a little tame compared to the abundance of full-frontal nudity and the current era of Grindr hard-on selfies. On the flip side, the film and the New Queer Cinema movement were ahead of their time by presenting more sexually fluid representations which modern day cinema is just now catching up on.

My Own Private Idaho is released on DVD/ Blu-ray this month