At first glance, the choice to make a courtroom mystery seems an unusual one for Kore-eda Hirokazu, who is best known for his subtle, entrancing family dramas and intensely affecting examinations of memory, family, loss and grief. But it doesn’t take long for his new film, The Third Murder, to prove that legal drama, in these exquisitely skilled hands, can be a perfect setting for further meditation on the thread of connected themes that wind through Kore-eda’s work from the beginning. If you’re familiar with his films, watching The Third Murder is like settling in to a familiar mood that’s very particular and rare in its poignant sweetness. It’s perhaps not the best introduction to Kore-eda’s work, though, as it feels a little colder, a little more distant than his very best films.

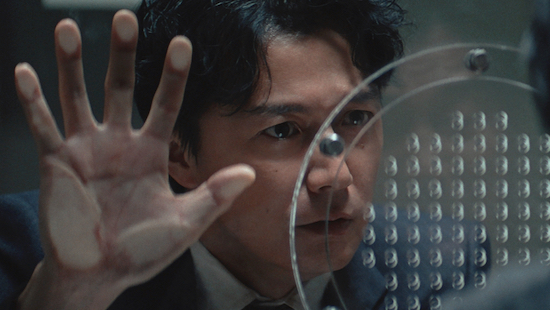

The Third Murder is a mystery story of sorts. Shigemori (Masaharu Fukuyama) is a lawyer assigned to defend Misumi (Kōji Yakusho), who’s been charged with murder for the second time in his life. Misumi has confessed to the crime, but Shigemori’s father was involved in the first case, and the son finds himself getting drawn into the question of Misumi’s guilt or innocence this time despite himself. Did he beat his boss to death and set his body on fire? More importantly, why did the murder happen?

The film offers the kind of contemplation on guilt and forgiveness that you might expect from a thoughtful legal drama. There are moments of restrained, but harsh shock; when discussing the ethics of the case with colleagues, Shigemori declares that "These days, victims think they can get away with anything." He’s used to having to deal with victims’ justifiable outrage, listening stoically as the widow asks if he really expects her to forgive Misumi. As lawyers, they have to side with the defendant, but do they have to empathise with him, understand him or forgive him?

Similarly, truth is positioned as separate from legal necessity. Discussing possible motives for the murder, a younger lawyer asks, "Which is the truth?" Shigemori answers, "Whichever is advantageous for the client, of course." He knows that the "truth" is unknowable. He’s not allowed to just get away with this, of course. The prosecutor accuses him of being "the kind of lawyer that gets in the way of criminals facing their guilt." Truth is real for her, even while the defence lawyers find things to laugh about. And the question of whether there is a truth that is knowable, an essential truth, is raised and left open.

Shigemori is suitable for this drama, because he’s not only cynical. He has ethical principles, as he shows when he tells his daughter she should bury a pet fish and lectures her on the importance of a proper grave. His view of the accusation begins to change when he finds out Misumi gave his pet canary a proper burial too. And this is our way into the themes of the story. Shigemori, Misumi and his victim all have daughters, and the stories of these three relationships intertwine and their subtle parallels and differences form the essential structures of this film.

Thoughts about parenthood, childhood, memory and nostalgia are constantly arising, and these bring to mind Kore-eda’s 1998 masterpiece, After Life. The newly dead must select a memory from life that will be recreated and filmed for them to take with them into the afterlife. It’s a meditation on the nature of storytelling, of how we recreate reality when we remember it, how retellings and re-enactments are just shadows of something that’s no longer accessible. The truth of the murder is only alive in memory, now, and Shigemori must learn a way to understand it that doesn’t fit in with the language of the law. Later, a scene where Shigimoro imagines himself as part of someone else’s happy memory, projecting himself into the scene as if he were directing it underlines this resonance.

Kore-eda usually centres his dramas on family and home, sibling and parental relationships, and The Third Murder is no exception. There’s a discernible pattern running through his work, a particular slant on what family relationships are, and it’s characterised by space and absence, tragedy and loss. Kore-eda’s contemplation of family takes him again and again to relationships fractured by circumstance, crime, or by death, and this in turn leads to examinations of loss, grief and mourning, then to remembrance and the nature of memory more generally, and back to the part memory plays in family relationships. It’s an elegant circle of deep thematic resonance, and as most of Kore-eda’s films occupy space in some part of this territory, each one adds to and deepens our understanding of the others

Kore-eda is sometimes compared to the celebrated, influential Japanese auteur Ozu Yasujirō, and it’s not hard to discern why, in context. Ozu is known for the subtlety and delicacy of his portrayals of family relationships and domestic drama, and for his technological and stylistic innovations, whose influence we can see in the work of directors like Kore-eda and other stars of contemporary East Asian cinema.

For example, as his style developed, Ozu moved his camera less and less, and placed it lower and lower. His way was to place the camera, and then allow the action to unfold in front of it. His style of cutting, too, was influential. Matter-of fact transitions, often using still images that are tangential to the narrative, work to remind the viewer that they’re watching a film, rather than aiming to keep the drama going. Such moments of stillness allow us time to sit with the images, rather than insist on rushing us along to the next plot point.

In his essay "Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema", David Bordwell describes these transitional images as "’intermediate spaces’, those pieces of space that not only come between two scenes but also lie between two sites of dramatic activity." He reminds us that Nol Burch considers that "the transitional passages achieve this goal by their stillness, their prolonged duration, and their lack of a compositional centre," and that Burch says "They demand to be scanned like paintings." Furthermore, these ellipses speak in the language of film to tell us about the gaps and absences in the relationships the films’ narratives describe. Each underlines the other.

Another comparison might be the way manga artists often create silence in between images, intervals marked by the absence of action.

These descriptions sound quite compellingly as if they could be about Kore-eda’s work too – and he does have a particular way of using spaces in narrative to allow the viewer time to reflect. He too will place the camera somewhere that allows us to watch something take place, unfold slowly, and leave room for the attention both to focus and to drift, something that deepens and enhances the experience of viewing.

But Tsai Ming-liang, Edward Yang and Hou Hsiao-hsien. to name just a few of the better-known contemporary East Asian filmmakers, also use stillness and space in comparable ways. Perhaps this is more of a development in cinematic style than something that can any longer distinguish just one auteur’s work. Indeed, in an interview with Peter Bradshaw in 2015, an interview with Peter Bradshaw) Kore-eda mentions that he takes comparisons with Ozu as compliments, but sees his work as "more like Mikio Naruse [the Japanese director of sombre working-class dramas] – and Ken Loach." This suggests that the social realist aspects of his work are important to him, and perhaps overlooked in favour of the poetic, but if trying to pin down what’s unique about Kore-eda’s work in particular, it’s perhaps most rewarding to use this as a prompt to look at how the two interact in the context of the themes he returns to over and over.

The key to understanding this is in that rich thematic territory Kore-eda occupies. Families – especially sibling and parental relationships – and what separation and loss means for those families, are at the centre of much of his work. He has focused on crime and its effect on victims before. 2001’s Distance is about the survivors of a cult that committed mass suicide after sabotaging a city water supply. The story of Nobody Knows (2004) is based on a real case of a mother who simply abandoned her children in an apartment and left them to fend for themselves for months. Kore-Eda’s film takes this incredibly sad story and somehow makes something wonderfully uplifting in its affect, but it’s vital for its success that in all its sweetness and lovely, subtle portraits of the complexities of sibling relationships, the film never loses sight of the horrifying reality of the story.

Since the beginning, too, the realities of grief and memory have haunted Kore-eda’s work. His first film, Maborosi (1995) is a sad, gorgeous meditation on loss. Without Memory (1996) is a documentary about a man who is left unable to form new memories after a brain injury, and how this has affected his family life. It’s beautiful. After Life, Distance (2001) and 2008’s Still Walking return to the theme of commemoration and remembrance of those who took their own lives. And then more recently, Kore-eda has focused more on how loss opens up gaps in familial relationships. The wistful I Wish (2011) is about two brothers living in different cities and the way they keep their bond alive. Like Father Like Son (2013) takes the theme further, with what seems like a difficult story about children swapped at birth blossoming into something wonderful. Our Little Sister (2015) does the same thing with a warm, poignant story of sisters adopting a younger half-sibling.

It’s true though that The Third Murder is a colder, sadder film than most of Kore-eda’s work. The characters are kept more at a distance, as if the courtroom and prison settings have drained some of the life from the story. The film’s look is also chillier and darker than that of previous films, and it’s a good thing that Ludovico Einaudi’s soundtrack is characteristically lovely, and works beautifully with Kore-eda’s images.

It remains a deeply satisfying film to watch, though, especially in its thematic resonance. For example, the snowy train trip the lawyers take up to Hokkaido reminds us of the importance of travel in these stories – the monorail in Nobody Knows symbolises an unattainable freedom, but the train journeys taken by the brothers in I Wish and little Suzu in Our Little Sister bring people closer. It’s things like this that bring us further into Kore-eda’s world. And when the mystery of the title – which is the third murder? – begins to resolve itself, the film’s solemnity and detachment resolve, too, into something profoundly heartbreaking.

The Third Murder is at cinemas now