Igor Stravinsky was still in his 20s when a dream of a girl dancing herself to death in a pagan ritual inspired him to come up with the thunderous, revolutionary Rite Of Spring. An avant garde ballet scored for a vast orchestra, it premiered in Paris in 1913, famously caused a scandal and made the Russian composer world-famous – a celebrity as we know one now, stopped in the street, mobbed, adored.

His career was already going spectacularly well. Just four years earlier, he had been plucked from obscurity by a visionary impresario called Sergei Diaghilev, who thought he heard a spark of genius in Fireworks, an immature Stravinsky piece that he’d seen performed in Saint Petersburg in 1909. With the killer instinct of a great A&R man, he first offered the unproven musician orchestration work with his new, Paris-based company, the Ballet Russes, then – after other, better-known composers turned him down – he gambled and gave Stravinsky a full commission for the 1910 season, The Firebird.

The Firebird – a ballet based on Russian fairytales and the first Diaghilev productions to have an all-original score – was a success that blindsided the music cognoscenti in Paris, including Debussy and Ravel, who said in a letter to a friend, “This goes further than Rimsky-Korsakov – come quickly.” Overnight, his life changed forever. Young, dandyish and diminutive at just 5’3”, he suddenly found himself in the company of Paris’s music stars and, within days, he’d met the city’s literary gods, including Marcel Proust, André Gide and Jean Cocteau.

The early burst of Stravinsky’s success happened in a crescendo of Diaghilev-commissioned Ballet Russes, starting with The Firebird, building with 1911’s Petrushka, and climaxing with The Rite Of Spring. Then war broke. He spent it with his wife and young family in neutral Switzerland trying out new, smaller-scale ideas, settled in Paris afterwards, and eventually ended up in America, where he died in 1971, aged 88.

Throughout his career, Stravinsky worked prolifically and with the luxury of having every note he composed performed and recorded. But here’s the strange thing: he’s often referred to as the most-significant classical composer of the 20th century, yet he didn’t really have another hit after The Rite Of Spring, and even by 1935 he knew that he was losing his crowd. “At the beginning of my career as a composer I was a good deal spoilt by the public,” he wrote. “But I have a very distinct feeling that in the course of the last 15 years my written work has estranged me from the great mass of my listeners… Liking the music of Firebird, Petrushka, The Rite Of Spring and The Wedding, and being accustomed to the language of those works, they are astonished to hear me speaking in another idiom. They cannot and will not follow me in the progress of my musical thought. What moves and delights me leaves them indifferent, and what still continues to interest them holds no further attraction for me.”

Who was he, and why is he so respected if his audience deserted him after what amounts to a three-album eruption of glory before the First World War? Despite his fame and the fact that there’s so much of him out there – music, books, and his every move was covered by the press – he’s a tricky one to decode. The New York Times’s classical music critic from 1950 to 1980, Harold C. Schonberg, called him a “chameleon”, and a recent biography by Jonathan Cross had him down as a kind of Russian matryoshka doll or, as Churchill said about Russia, “a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma”. These descriptions would have delighted Stravinsky, who thrived on being unpredictable (and talked about), but first, let’s get down and dirty with The Rite Of Spring, one of the greatest pieces of music ever penned.

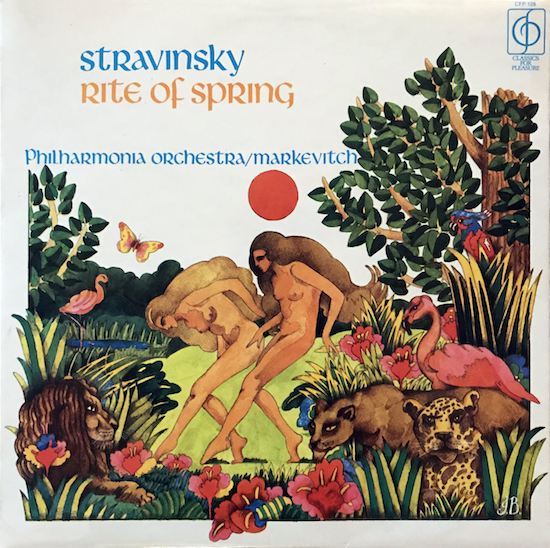

A quick measure of any recording of The Rite Of Spring is how hard the orchestra hits ‘Augurs Of Spring’ – the huge, repeated crunch of dissonance that starts the action proper after the ballet’s eerie introduction. To Stravinsky, the beginning of spring was a moment of high drama – the great thaw when the thick Russian ice groaned and cracked – and in the version I’ve chosen for this column (Igor Markevitch conducting the Philharmonia in 1959, which was reissued in the 70s on a budget label with the cover above), that violent chord sounds like a barking dog, ferocious and bracingly alive. Surely, you’d guess, it’s that point in the score – just under four minutes in – which sparked the riot that’s supposed to have taken place when Pierre Monteux conducted the premiere in Paris on May 29, 1913. But, according to reports, titters and boos were heard straight off the bat, with the curtain down, as the introductory wail of a strangled, high-pitched bassoon filled the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées. French composer Camille Saint-Saëns is meant to have scoffed, “If that’s a bassoon, I’m a baboon!” In a nearby box, Debussy is supposed to have said: “It’s terrifying! I don’t understand!”

How much of this is true? We don’t know. There was a commotion for sure; perhaps someone got punched; Stravinsky – according to himself – left his seat and headed backstage in a panic; and Diaghilev is thought to have demanded that the house lights be flicked on and off to try and pacify the crowd (the reverse happened). Ever the canny impresario, he might also have encouraged unrest by hyping up the ballet in a press release beforehand (he promised “a new thrill” that would “doubtless inspire heated discussion”) and possibly even giving out free tickets to radicals and progressive aesthetes, presumably hoping they would take on any philistines hissing in horror at Stravinsky’s music or the Vaslav Nijinsky-choreographed anarchic, free-form dance.

But it helps to keep some perspective here: this was a ballet, not a Black Flag gig, everyone would have been in formal dress and if the riot, as some believe, was fought on a fault line between modernists and traditionalists, the modernists clearly won – Stravinsky, Nijinsky and the dancers are known to have taken many bows, and there was little or no trouble at future shows.

The Rite Of Spring is divided into two parts – ‘The Adoration Of The Earth’ and ‘The Sacrifice’ – and the plot, if you could call it that, is intentionally basic and impressionistic: a pagan ceremony celebrating spring takes place over a number of choreographed episodes, culminating in a girl being chosen from a group to die in a closing, exhausting, freak-out of a sacrificial dance. And although, as Alex Ross points out in his book The Rest Is Noise, ethnic folk music is weaved into the genetic code of a score that reassembles a multitude of different sounds, rhythms and textures in cubistic montages and collages, “The notion of a female sacrifice was Stravinsky’s special contribution… He was giving voice not to ancient instincts but to the bloodthirstiness of the contemporary West. At the turn of the century, purportedly civilised cities societies were singling out scapegoats on whom the ills of modernity could be blamed… Against this backdrop, the urban noises in Stravinsky’s score – sounds like pistons pumping, whistles screeching, crowds stamping – suggest a sophisticated city undergoing an atavistic regression.”

Because The Rite Of Spring is so brutal, it’s tempting to think of Stravinsky as a punk rock character, and in some senses he was. Almost single-handedly he re-set music, killing off 19th century Romanticism with a modernist, discordant sound, and he also crossed over to become an enduring popular-culture icon. There can’t be many post hardcore bands, like Guy Picciotto and Brendan Canty’s pre-Fugazi group Rites of Spring, named after classical works, nor many films made about a classical composer’s presumed philandering, like 2009’s Coco Chanel & Igor Stravinsky. But he didn’t start his revolution in some unordered, spasm of youthful energy – he plotted his insurgency note by note with a logic and precision that bordered on the psychopathic. Then, within moments of becoming an enfant terrible, he made a dramatic change, deciding that the music of the future should learn from the lessons of the distant past. In short, after the war, he became a neoclassicist, and that career curveball, even today, seems no less expected than The Rite Of Spring itself.

Stravinsky wasn’t a child prodigy. He was born in 1882 in a suburb of Saint Petersburg to a father who was a well-known opera singer and a mother who was an amateur pianist and also sang. He was surrounded by music as a kid and loved it, but he didn’t show much natural talent on his chosen instrument – the piano – nor was he encouraged by his strict parents, who insisted he study law. Distracted and unhappy, he didn’t start composing until he was 19, and he was still a law student at the University of Saint Petersburg when he became friends with Vladimir Rimsky-Korsakov, son of

Nikolai, a key member of what was dubbed The Mighty Handful or New Russian School.

Stravinsky’s stern, cold father died in 1902, freeing him to pursue a career in music. The same year, he stayed with the Rimsky-Korsakovs in Germany, persuaded Nikolai to give him lessons and it became the only formal training he received. He was devastated when he learned of his teacher’s death in 1908 and hardly a fully-formed composer by the time. His pieces up to then were promising but ordinary and you could argue that The Firebird is his first fully realised work.

How did he do that? How did he go from a zero to a hero in a single commissioned score? Perhaps that’s as good a definition of genius of any, but I think it also helps to know something of how he worked.

Whether by circumstance or design, and probably both, when Stravinsky was in Switzerland during the war he moved on from composing grand, nationalistic works for large orchestras and focussed on a number of pieces that were simmered down and smaller in scale but no less bold. One was called The Soldier’s Tale. It’s quirky and jazzy, and includes text by the Swiss writer C. F. Ramuz, who had this to say about Stravinsky’s work table: “His writing desk resembles a surgeon’s instrument case. Bottles of different coloured inks in their ordered hierarchy each had a separate part to play in the ordering of his art. Near at hand were india-rubbers of various kinds and shapes, and all sorts of glittering steel implements: rulers, eraser, pen-knives, and a roulette instrument for drawing staves, invented by Stravinsky himself. One was reminded of the definition of St. Thomas: beauty is the splendour of order.”

Ramuz added that his scores were “magnificent” and that he was “in all matters and in every sense of the word a calligrapher”, and these details provide real clues to Stravinsky’s art and mind. His music could be fierce, like The Rite Of Spring, or spiky, like his brilliant Violin Concerto from 1931, but it’s united in its supreme sense of organisation and craft. And it’s really no wonder that the piece he used to mark the beginning of his neoclassical period – a 1920 ballet called Pulcinella, for which his friend Pablo Picasso designed the costumes and sets – was hugely influenced by the greatest past master of musical precision and logic, J. S. Bach.

In The Rest Is Noise, Alex Ross identifies another piece from 1920, Symphonies Of Wind Instruments, as the moment when Stravinsky scrubbed off his own history. With irony, it was dedicated to Debussy, who had died in 1918 and was something of a rival before the war. His mystical, hallucinogenic take on the avant-garde competed for attention in Paris with Stravinsky’s forceful and physical collages of sound, but they admired each other and Debussy was prone to offering his younger colleague advice. “Cher Stravinsky, you are a great artist!” he wrote to him in 1915. “Be, with all your energy, a great Russian artist! It is a good thing to be from one’s country, to be attracted to the earth like the humblest peasant!”

Stravinsky responded cheekily, basing Symphonies Of Wind Instruments on a Russian Orthodox funeral service, whose, as Ross writes, “solemn chant may signify that the composer is ritualistically burying his old self alongside the body of Debussy. A string of catastrophic events – the demise of tsarist Russia, the onset of the Russian Revolution, the early death of his beloved brother Gury – meant that by 1918 the world of Stravinsky’s childhood had been effectively erased.”

And therein lies another clue to why Stravinsky remains such a slippery fish in the history of music. When he left Russia for Switzerland, he left for good – returning only in 1962 for a visit – and he wasn’t even buried in the country of his birth, asking instead to be laid to rest in Venice, not far from the tomb of the man who gave him his break, Sergei Diaghilev. He became a French citizen in 1934 and an American in 1945, and he loved casting himself as something of an international man of mystery, a true 20th-century cosmopolitan, adept at getting by in whatever city he chose and writing music that was geographically hard to place. He savoured the respect he earned in all countries, and in all corners of the music world. When Charlie Parker came to Paris in 1949, he famously improvised the first notes of The Rite Of Spring into his solo on ‘Salt Peanuts’, and in New York two years later, Parker incorporated a motif from The Firebird into ‘Koko’, which apparently caused Stravinsky to spill his scotch in joy.

There was one more stage in Stravinsky’s extraordinary career. Part of Debussy’s fear when Stravinsky was metamorphosing into a neoclassical composer was that he was “leaning dangerously towards the Schoenberg side” – the side of atonal, twelve-tone music pioneered not just by Schoenberg but Alban Berg and Anton Webern. Their revolution in music, which became known as serialism, ran parallel to Stravinsky’s experiments in the neoclassical style, and grenades were thrown over the fence, including by Schoenberg, who wrote a satire about Stravinsky in 1926 and set it to music. It begins, “But who’s this beating the drum? / It’s little Modernsky / He’s had his hair cut in an old-fashioned queue / And it looks quite nice.”

Stravinsky himself could be acerbic about other composers – especially in a series of interview books that he published with the writer and conductor Robert Craft later in his life – but his opposition to serialism cooled as he grew older and he dramatically wrote a number of twelve-tone pieces in the 1950s and 1960s, stunning the music world. He was accused of jumping on the bandwagon, but, as New York Times critic Harold C. Schonberg wrote in 1970, “Threni and other works still had the old Stravinsky sound… Stravinsky merely did with serialism what he had done with any other form of style that passed his way: put in through the Stravinsky filter.”

Still, if Stravinsky had lost, as he said, “the great mass of my listeners” by 1935, changing to serialism in the 1950s was hardly going to win them back. And because he could be pig-headed and controlling, more mainstream projects – like scoring Hollywood films – always fell through (although The Rite was used in Disney’s Fantasia in 1940). Instead, he left an enormous body of work created entirely on his own terms – uncompromising and uncompromised – and by 1961 it dawned on him that perhaps the classical music-buying public wasn’t his core audience. “My music is best understood by children and animals,” he said, and maybe he wasn’t joking.

In the same essay – published a year before Stravinsky died – Harold C. Schonberg mused on Stravinsky’s then-position in music, and how he might be remembered, concluding: “Much of the pleasure in listening to his music comes from sharing the mental processes of a superbly organised mind – a mind with a good deal of perkiness, to be sure: a fascinating mind; a witty and aphoristic mind; but above all, an organised mind. In his music there is no padding, no inflated or uneasy ‘developments’… He can all but hypnotise a music lover who has a high degree of sophistication; but the sophisticates are, after all, a minority of the musical public. It may be that Stravinsky, the ‘world’s greatest living composer’, will end up living more for what he did to music rather than what his music did to the majority of his listeners.”

There may be some truth to that, but – for now – Stravinsky seems no less a presence in the lives of music fans than he was when he was still alive, and no less of an enigma. In 1989, a ding-dong broke out between two Stravinsky scholars about a sentence he’d written in a 1933 letter to a publisher: “I am surprised to have received no proposals from Germany for next season, since my negative attitude toward communism and Judaism – not to put it in stronger terms – is a matter of common knowledge.” One expert (Robert Craft, Stravinsky’s collaborator on his interview books) believed he was being flippant; the other (a musicologist from the University of California, Richard Taruskin) suggested that “anti-Semitism, for him, was no object”.

In the 1930s, he also expressed admiration for Mussolini, but these freak comments or stains in his story – depending on how you look at them – barely trouble his legacy. Stravinsky is still lauded and he still makes news. In 2015, a long-lost piece – Funeral Song, written in memory of his teacher, Rimsky-Korsakov – was found in a pile of old manuscripts in Saint Petersburg. A Guardian report on the discovery was shared more than 60,000 times – a staggering figure for a news item from the world of classical music. Stravinsky lives, like an eternal personification of springtime – seemingly forever budding, forever fresh, forever sharp.