“If I make another album, it will be to prove that I am the best, writing in words of fire in what is a minor art form. I don’t want to go down in posterity. What has posterity ever done for me? Fuck posterity.”

When Serge Gainsbourg performed the chanson ‘New York USA’ in 1964 he might as well have been singing about the moon. “J’ai vu New York,” he sang, apparently suspended from a high-rise made possible by blue screen in a French TV studio. “Oh! c’est haut, c’est haut, New York…” In reality he would’ve had no first hand experience of the city with the impressions he did have built up from books, newspapers, cinema and TV. Pictures from the moon wouldn’t enter our living rooms until 1969 of course, though dark, desiccated and crepuscular, the lunar surroundings would have appeared less alien than an aerial view of the extravagant Lower Manhattan Financial District in the mid-60s. The first office skyscraper at La Défense, la tour Nobel, didn’t appear in the burgeoning Parisian financial hub until 1966.

Like many stars of his generation, Serge was a little bit obsessed with America: the glitz, the brashness, the cadillacs, the pop art, the movies and the rock & roll. His contemporaries Johnny Hallyday, Eddy Mitchell and the lesser known Ronnie Bird made decent livings performing knocked off R&B and R&R songs from across the Atlantic translated into French and passed off as their own, which is perhaps why Halliday picked up the nickname “the French Elvis” and the less catchy “the biggest rock star you’ve never heard of” (the latter epithet assumes you’re not from one of the 29 countries that recognises French as a spoken language).

Gainsbourg wrote his own songs and songs for everyone around him too. He was a one-man Tin Pan Alley for the yéyé generation and he was prone to experiment with the sounds around him and curious about the sonic praxes of other territories too. ‘New York USA’ features on Gainsbourg Percussions, an album inspired by the African musicians Babatunde Olatunji and Miriam Makeba back when appropriating music from Africa was virtually unheard of. In true colonialist style, Serge forgot to credit Olatunji and Makeba, but that has been rectified on more recent pressings.

Two decades later the world had opened up. Discovering the cultures of other territories was no longer the preserve of explorers and the very rich. Passenger flights on Concorde, which had been in service for nearly a decade, could get you from Paris to New York in three and a half hours (though you’d need loadsamoney to enjoy that particular mode of supersonic aviation). In 1984, Serge took off for the new world in search of new sounds. His fascination with the States in the 60s could now be turned into something of significance, and yet more fortuitously his musical weaknesses at the time were disco, funk and hip hop.

1984’s Love On The Beat was considered a return to form after the lacklustre performance of his 1981 album Mauvaises Nouvelles Des étoiles which only sold around 100,000 copies. It was a reggae sequel of sorts which saw Sly Dunbar and Robbie Shakespeare return after the great success of the original Aux Armes Et Caetera, but what had seemed like a shot in the arm was already passé two years later. The 1979 freggae chef d’oeuvre had surprised many by becoming Gainsbourg’s biggest selling album in France, and it still is. It’s probably now safe to say Mauvaises Nouvelles Des étoiles will never garner the sort of critical and cultural reevaluation Histoire De Melody Nelson did (which believe it or not, had sold just over 70,000 copies by 1983). Serge must have felt some trepidation then when he decided to reuse the core of the team that made Love On The Beat for You’re Under Arrest.

Back came producer Philippe Lerichomme, who’d sat in the control room for the previous four Gainsbourg albums dating back to L’Homme à Tête De Chou in 1976. Billy Rush, the New Jersey guitarist, co-produced the two “American” albums alongside Lerichomme. A Springsteen acolyte who’d written with Muddy Waters and Bo Diddley, Rush earned his stripes working on Serge’s daughter Charlotte’s 1986 debut solo record Charlotte For Ever. Gainsbourg fans who’ve never been able to fully embrace the singer’s 80s direction often lay the blame at Rush’s door.

In his book A View From The Exterior, Alan Clayson points out that Gainsbourg’s last album is a consolidation of his penultimate one. There’s some truth in that, but what You’re Under Arrest attempts that Serge hadn’t properly tried before is hip hop, or at least – and let’s be clear here – a facsimile of how hip hop sounded in 1987 to the ears of a 58-year-old Frenchman. Backing singer Curtis King Jr gamely steps up to the mic to deliver what sounds like a cypher but is more likely the product of Serge’s poor command of the English language: “You’re under arrest / Cos you’re the best / Slippety slam bah-boom bam…” These are words thrown together that make little sense delivered by a session singer not known for his flow. Perhaps the most obvious thing to point out here is that you don’t ordinarily get collared by the old bill for being “the best” – it’s the stuff of nursery rhymes from the ‘Rapper’s Delight’ school of Learian nonsense. There are also some stuttering “G-G-G-G Gainsbourg”s thrown in, which sound as though they’re performed in one take by King Jr rather than by a sampler or a scratched record, which was how it was supposed to be done at the time.

That all said, there’s something gratifyingly quaint about what many see as a misstep – a snapshot of the naivety the explosion of a new musical genre into the mainstream caused. Serge certainly had enough confidence in his own talents to believe he could subsume any musical ideas old or new and bring them into his own creative domain, and he almost pulls it off. Anyone scoffing clearly has a short memory too. It’s often said that his first proper foray into hip hop was thankfully his last, but whoever says that surely falls into a trap Serge fell into himself, in believing that authentic rapping has to be performed by an African-American. As an in demand backing singer who worked with everyone from David Bowie to Celine Dion, Curtis King Jr was unable to do the promo in France because of other commitments back in the US, so a sinewy, dreadlocked dancer was hired to mime the words as he pirouetted around a flabby and visibly ailing Gainsbourg, a juxtaposition as preposterous as it was awkward. So herein lies the rub: perhaps the title track was the chanteur’s first (and last) attempt at counterfeiting a commodified version of New York hip hop, but Serge had actually been rapping for years.

His inimitable gallicized sprechgesang had become his most recognisable leitmotif, always with a burning Gitanes in hand. Notable early examples include 1967’s speaky ‘Bonnie & Clyde’ duologue with Brigitte Bardot, the 1968 single ‘Requiem Pour Un Con’ (or requiem for a dick), an impish eulogy set over an abrasive backbeat, or the growly discontent of ‘Initials B.B.’ from the same year, which was a very public statement about the heartbreak one feels when Brigitte Bardot dumps you and goes back to her playboy husband. What’s more, ‘Bonnie & Clyde’ featured a tape loop with a disembodied woman’s voice acting as part of the percussion, while the main hook of ‘Initials B.B.’ was stolen directly from Dvořák’s New World Symphony. Serge would think like a hip hop producer, purloining from the classical greats – and in particular Chopin – throughout his career. Electral love hot potato ‘Lemon Incest’ took the Polish composer’s ‘Tristesse’ and transposed it over a disco beat; ‘Jane B’ bastardised Prelude 28 and laid it over a cool jazz rock shuffle. And as previously mentioned, sampling African musicians and trying to pass it off as your own oeuvre arguably demonstrates a hip hop sensibility. So to suggest the title track from You’re Under Arrest was the first stab at urban music from an ageing French lothario would be wide of the mark; it was more the valediction of a career in experimentation by a proto-hip hop master.

The title track is also notable for a laboured pun on the Bronx, where Serge pays tribute to Bronski Beat, who’d covered ‘Comment Te Dire Adieu’ as ‘It Hurts To Say Goodbye’, a song originally written for and made famous by Françoise Hardy in 1967. Gainsbourg was late to the cause of gay rights, dabbling on the previous record with the chanson ‘Kiss Me Hardy’, which involves him ‘coming out’ of a painting by Francis Bacon to make love to another man. Was this in solidarity with homosexuals or just another attempt to shock his audience, or a bit of both? With Serge there are always layers to unpeel.

You’re Under Arrest doesn’t have that many champions but it has one in Dev Hynes, Lightspeed Champion, who incidentally stars alongside Charlotte Gainsbourg in her new video for ‘Deadly Valentine’. He told NME: “Gainsbourg always adapted to the times; here he went deeper into dance and tight ‘80s funk type grooves with his songs. On top of this, he had refined his songwriting to its most articulate – the lyrics were surreal and very tongue in cheek, more so than usual. Then the melodies were all so precise; he recorded his last two records using amazing session musicians, interestingly enough, which seems to be the reason most people are not a fan of his later work. The word sterile gets tossed about frequently.”

Sterility was probably necessary to offset the dirty needles in the concept narrative. Partly inspired by his live in lover, Bambou, Serge decided to wage his own war on drugs. You’re Under Arrest is set in New York and revisits the familiar Lolita motif, where the protagonist pursues misadventure with a black teenage girl called Samantha – who he later gives the heave-ho on ‘Baille Baille Samantha’ because he’s an old grump and she’s hooked on smack (“Je suis à cran, tu es accroc”). The line between avuncular protector and papa sucre is more than blurred with the invitation to ‘Suck Baby Suck’ (perhaps this is the “tongue in cheek” Hynes is talking about), all whilst listening to a CD of “Chuck Berry Chuck” or watching any Tex Avery cartoon the girl desires as he owns the video box set. Written with the sweetest of melodies, older listeners would no doubt be reminded of ‘Les Sucettes’, a song about lollipops with a risqué double meaning that poor France Gall had to have explained to her when she was already riding high in the French charts in 1966. Serge no doubt felt the need to up the ante with each release in order to shock, and whenever he unleashed the “Would you like to see some puppies?” routine he usually elicited the response he craved.

Gainsbourg no doubt found funny the stink he caused writing lyrics about abusing minors, but perhaps the biggest shock came with the ballad ‘Aux Enfants De La Chance’, a moralistic plea to children everywhere not to take drugs. As somebody literally on his last legs from alcoholism and copious cigarettes (there was talk of his lower legs being amputated before he died of a heart attack), it would be fair to suggest a degree of hypocrisy, though with children of his own, including the then one-year-old Lulu, his concerns were probably genuine. Songs about just saying no to drugs were in wide circulation in the late 80s, and the journalist Jody Rosen remembered living in Paris and always hearing ‘Aux Enfants De La Chance’ playing whenever he went into his local tabac. “Des shoot et du shit…” sang Serge with his familiar brand of franglais, and “touchez pas à la poussière d’ange” (don’t touch angel dust). Another franglais pun comes on the slick and funky ‘Five Easy Pisseuses’ – a play on the title of the Bob Rafelson movie that won Jack Nicholson an Oscar, with the “pisseuses” likely a slang term for young, inexperienced girls, though Sylvie Simmons in A Fist Full Of Gitanes suggests it means “a weak-bladdered female”. ‘Five Easy Pisseuses’, with its slow building chorus and gospel singing towards the conclusion, is a terrific song worthy of Serge’s swansong, even if, like on ‘Suck Baby Suck’, the words are a bit hard to stomach.

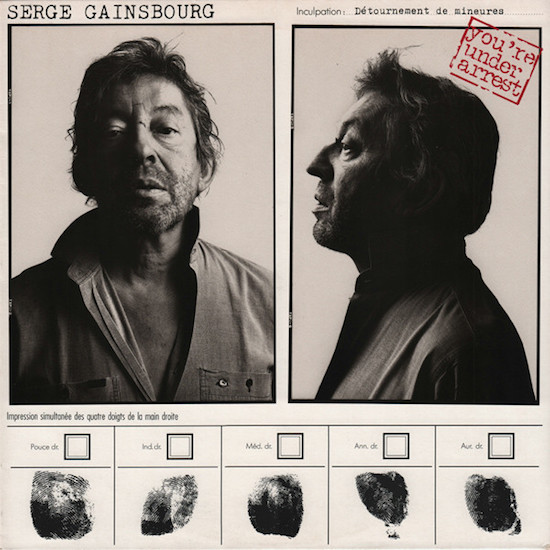

Perhaps the biggest contrast between Love On The Beat and You’re Under Arrest is the cover art, which is illustrative of how quickly the singer went downhill in the space of three years. Gainsbourg might have been a hopeless dipsomaniac bit in 1984 he still had the last vestiges of a vanity streak. He’d been photographed blowing smoke rings done up in drag by his friend, the brilliant US-born French photographer William Klein. In order to decrease the poches sous les yeux, which in Gainsbourg’s case were more like valises, he’d forgone alcohol for nearly a fortnight ahead of the shoot in the hope that he would appear more glamorous. He had no such worries for You’re Under Arrest featuring portrait and profile mugshots of a dishevelled scallywag with cuts to his nose and forehead, and denim prison garb worn open at the neck. Suffering from acute neuralgia and living in the groggy hinterland where hangovers and benders become one and the same, Gainsbourg managed to maintain staggering productivity for a man not so much in his autumn years as one being sized up with a tape measure on Boxing Day. As well as his own records during the period, he also produced and wrote them for others, from French film star Isabelle Adjani’s very good Pull Marine in 1983, to Vanessa Paradis’ 1990 second album Variations Sur Le Même T’aime, which has its moments – though the only thing worse than overwrought 80s production is overwrought 90s production (which it suffers from). As a final statement to the world, You’re Under Arrest is a far better, nihilistic summing-up of a brilliant and controversial career. What use is posterity to a dying man? Fuck posterity.

Finally we should mention Serge’s cover of ‘Gloomy Sunday’ – known as the Hungarian suicide song because so many listeners are supposed to have taken their lives after hearing it (there are no statistics). Covers over the years include Billie Holiday, Sinead O’Connor, Lydia Lunch, The Associates, Anton LaVey and Diamanda Galas to name but a few, and the urban myths that surround it are numerous. Whether Serge knew this would be his final album is doubtful, even if deep down he suspected it, but nevertheless a cover of Rezső Seress’ 1933 psalm to seppuku feels rather like the full stop of a career that was in many ways one long and beautifully handwritten suicide note with many more laughs along the way than was strictly appropriate. Serge died four years after making You’re Under Arrest of a heart attack in March 1991, a month before his 62nd birthday. Were he still alive today, he could have written the requiem for the American Dream.