An entirely self-taught pianist and composer, Dmitry Evgrafov has been self-releasing his music since he was 17.

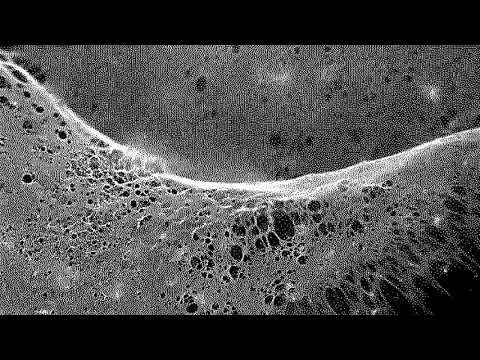

He signed with FatCat’s 130701 imprint in 2015, releasing an album titled Collage and last year an EP called The Quiet Observation. Now he’s set to follow those first releases for 130701 with a second album for the label, titled Comprehension of Light. Premiering above is a video for ‘Tamas’ from the album, with monochrome animated visuals set to the track’s sweeping arrangements and woodwind sounds.

The album was recorded during a focused period of writing for Evgrafov which took place between late 2016 and early 2017. His previous releases were stitched together from unrelated works that had not been produced with an album or EP concept in mind, but Comprehension of Light saw Evgrafov writing with a concept and set intention in mind.

The album is due out tomorrow and can be pre-ordered here. We spoke to Evgrafov about the record ahead of its release, and you can read the results of that conversation just below.

You’re a self-taught pianist. Do you feel that has allowed you to experiment more as a producer and composer without the limitations of learning traditional techniques?

Dmitry Evgrafov: It is a very seducing thing to think that way. The romantic image of a naive dilettante is charming, undoubtedly, but I hardly believe that any of the highly productive professional composers ever said something like ‘I wish I did not know anything about orchestration rules!’. In my case being self-taught brings more challenges than advantages, I always have to invent certain work-arounds in my working process. Everyone thinks that these patches and oddities are part of my ‘unique style’, but in reality I’m merely reinventing the wheel over and over again.

This new release was written with a specific concept in mind, whereas your other releases were put together from different sketches and commissions. Why did you decide to approach this record with a concept?

DE: To my shame, only recently I discovered the joy of reading good literature and I was stunned by how efficient and clear the information and artistic view is transferred through text in comparison with music. In that sense, music is the most abstract form of art, especially instrumental music – nothing is concrete and univocal in it, it can be interpreted freely in any way. Obviously, it is a double-edged sword, and in my case it was a limitation.

On this album I needed to depict a very precise and clear statement, needed to bring a voice to what I do and what is important to me. Because of that I worked really hard on the emotional carriage of each track, on the track titling, on the artwork and supporting text, on the music video. All of that was working towards the single goal of transferring the process of comprehension of light.

You cite a "long and difficult personal journey from darkness to light" standing behind this release – how did you bring that to life in the music itself?

DE: As I said, it required some conceptual, stylistic and artistic limitations. Other than that, I used some strong musical and psychoacoustic tools to develop either the sense of frustration, the feeling of fulfilment or something in between. For example, on the intro track I took some choir samples and played them back in a pine forest while standing about 30 meters deep into the woods. The resulting muffled, ‘lost’ choral voices instantly evoke the feeling of something long forgotten, a bleak memory of pure past and origins.

Another example is on ‘Wandering’: this is a string quartet piece which, despite being fairly tonal and harmonic, rambles through all 12 tonalities, one by one, occasionally lingering in some, yet never finding rest in any, which in the end results in a very uneasy and suspended feeling.

A lot of the record has a grand, cinematic sound. Have you been influenced by the work of many other composers who create music of this kind, specifically in the world of film soundtracks?

DE: Generally I do not listen to the film soundtracks and to be honest I express a certain amount of depreciation towards the generic ‘cinematic music’ that can be heard in almost all movies. Film music has a very strong functional purpose and can be a powerful emotional tool in conjunction with the picture/story, but you just cannot ignore how bleak most soundtracks sound when listened out of context.

There are few exceptions of course, wonderful wonderful exceptions: recently Jóhann Jóhannsson’s Arrival; most scores by Williams and Morricone; very few compositions from Hans Zimmer’s scores and some other composers. They have such depth and detail that there is no way of hearing them all in the theatre. That said, somehow I have an innate ability to make so-called ‘cinematic’ music. So I am trying to marry these two worlds: the world of subtle details and nuances and and the world of overwhelming orchestration and vivid musical colours.

You worked with a number of other musicians on this record, which is a break from your mostly solo work before. Why exactly did you take that decision? Did the scale of the project naturally involve opening it up to more people?

DE: There were a few places in which I felt myself not good enough, for example in lush ambient stuff, so I asked Abul Mogard (who is an ambient music genius) to co-write one composition with me. Also, there is a guy called William "Memotone" Yates whom I met online. I heard some very mournful and atonal pieces on his SoundCloud page, so I just asked him to add some dissonant-yet-beautiful clarinet and cello parts for my tracks, because I do not have enough patience and knowledge to make such music.