The story of Idris Ackamoor and The Pyramids is the stuff of deep jazz legend. Formed in 1972 by students of the avant-jazz genius Cecil Taylor, The Pyramids were among the first jazz groups to travel extensively throughout Africa, playing with Dagomba drum circles in Ghana, living with the Massai in Kenya, and visiting the rock-hewn churches of Lalibela, Ethiopia. These experiences fed into their performances, which combined funky, freewheeling Afro-jazz with dance and ritual. After returning to the US, The Pyramids recorded three private press and became fixtures of the vibrant San Francisco music scene, before disbanding in 1977.

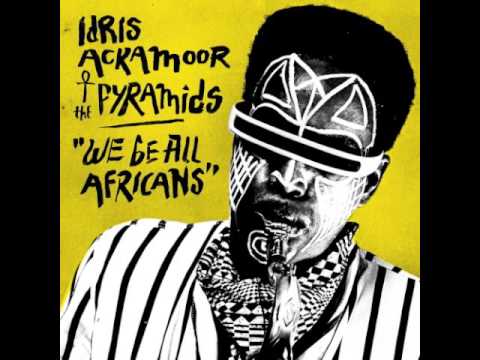

Over the years, The Pyramids’ albums became collectors’ items, and with the advent of the internet, their legend only grew. This renewed interest led to the reissue of their albums and the reactivation of the project. For the past decade, Ackamoor has toured and recorded with various incarnations of The Pyramids, featuring a rotating cast of original members and new additions. Their comeback album Otherwordly dropped in 2012, followed by 2016’s ebullient We Be All Africans on the always on point Strut Records.

Born Bruce Baker in 1951, Ackamoor grew up in the South Side of Chicago. He fell in love with music at an early age, taking lessons in saxophone, clarinet, piano, violin and trumpet. At High School, he gravitated towards sports. ‘I was really attracted to basketball,’ he tells me over Skype, ‘[But] you couldn’t be in the band and the basketball team at the same time because the band played for the basketball games. So for four years I just played basketball and did what most teenagers do, you know, go to parties, chase girls, study.’

He went to college on a basketball scholarship, but during his first semester, he had an epiphany that music was his true calling. Ackamoor subsequently transferred to Antioch College, a liberal arts institution in Young Springs, Ohio, with an experimental work-study programme and separate black dormitory. In the meantime, he took lessons with his ‘saxophone guru’ Clifford King, who had played in big bands in the ’30s and was ‘the teacher of choice for many of the great Chicago saxophonists.’

Talking to Ackamoor over Skype during some time in Knoxville, Tennessee, where he has been on tour with his music-theatre company, Cultural Odyssey, we covered his education under free jazz pianist and poet Cecil Taylor, the formation and re-emergence of The Pyramids and what fans can expect from live shows by the current incarnation of the group.

At Antioch you studied under Cecil Taylor. What were the most important lessons he taught you?

Idris Ackamoor: My major was music and I was beginning to form my own group. Cecil came about maybe a year and a half later. I was a member of his Interstellar Black Music Ensemble which was made up of about 25-30 musicians. Many of them were students, and he had other musicians who were following him around from his previous college. So I was a member of the alto section and some of the other members were Jemeel Moondoc, Bobby Zenkel – a fabulous saxophonist from Philadelphia who was also a member of my section – and of course Margaux [Simmons], one of the original Pyramids, was part of the flute section. Kimathi [Asante – Pyramids bassist] was part of the bass section, so we all were members of Cecil’s ensemble and we were studying some of the most incredible things.

I’ll never forget when Cecil gave audition. It wasn’t about music – there would be sympathy exercises. He didn’t worry unnecessarily about how fantastic a musician you were, he wanted to know how well you would take his directions. One of the other things that I learned from Cecil, I was so surprised, when Cecil would give us the pieces, there was no music paper, no musical notes. Cecil had you write in the letters. He would say ‘okay, go C to G then B flat’ and he would just write the letters instead of notation.

Is that an approach you’ve used in your own music?

IA: Well, I have, but not particularly. I still write my music down with notes because the influence that Cecil had extended beyond the written page. It had more to do with the qualities and the concept of improvisation and spontaneity and intensity. That was one of Cecil’s trademarks, the amazing intensity of his solo, of his improvisation. The concept, they would say, was you were playing out. Basically you were playing an intense music that had no meter, it had no rhythm, it was out. It was like John Coltrane’s Cosmic Music. But it was also very in because Cecil could be very, very intense, while at the same time he could be very beautiful, very lyrical. He went through complete extremities with his music. It was the time of the Black Power movement and there was a lot of anger, but a lot of people confused the music with being angry. The music wasn’t angry, the music was cosmic. Even though Cecil was very much trained in the European tradition, he was very much an African-American who was influenced by America, and consequently his concept of improvisation had a lot to do with possession by music. If you look at the ritual music in Africa, in the diaspora in Haiti, the idea of possession and creating a feeling of possession, that’s what Cecil was doing. If you saw him playing it was almost like he was being possessed. But the same time he was totally in control.

So the Pyramids emerged out of that context?

IA: Antioch had an education abroad programme. I wrote a proposal for me and Margaux to go to Europe and form a jazz band, work in Europe for a period of time, which ended up being about three months, and then go to Africa and study and tour and live there for the rest of the year. And so myself, Margaux and Kima left Antioch in the summer of ’72 and we arrived in Besançon, France. We met a drummer called Donald Robinson in Paris, but we decided we weren’t going to stay in Paris, because Paris at the time was a little, I wouldn’t say it was overpopulated, but there were a lot of jazz musicians there: Frank Wright was there, Muhammed Ali, Dave Burrell. We decided to go straight to Amsterdam in the Fall. We began to work as a trio: Margaux on flute, Kimathi on electric bass, myself on alto. Donald joined us a few weeks later and we began to work at all these government sponsored concert halls with names like the Kosmosis, the Octopus, and we also played at the Paradiso, which is still there. We did radio shows, we just played a lot as The Pyramids, and at that time we were coming straight out of the Cecil Taylor theory so we were very, very avant-garde. We played music to make fire, we played to make music burst out of our bodies. A poet wrote that about one of our shows in Amsterdam.

Africa was the ultimate destination, but were you already influenced by its music?

IA: The African influence was still to come. The biggest influence was Cecil Taylor, and a little bit of our own upbringing, the funk. It was really very original music. We still had rhythm because our eyes were still on Africa, but we hadn’t gone there yet. We arrived in Africa in December ’72 and we took up residence in Ghana. Donald, he thought he was going to be able to drive all the way to Africa, in a van, get on a boat, but it broke down just outside Amsterdam. Myself, Margaux and Kimathi travelled to Malaga, Spain, and we flew to Tangier, and we stayed in Morocco for several weeks and then we travelled to Rabat, Casablanca, and then we flew from there to Dakar, Senegal [where we stayed] for about a week. We finally ended up at Accra, Ghana and that’s where we started to live.

I understand you were going to the clubs in Accra, seeing people like Hugh Masakela?

IA: Hugh Masakela was playing with Hedzoleh Soundz. We would sometimes visit one or two of the clubs, but we were mostly taking in the music that was all around us. I mean, you could go to the marketplace and they’d be playing in the marketplace, and there would be griots playing music on the streets, so we were really taking in the traditional music of the culture of Ghana. Myself and Margaux, we took a life-changing three-week trip by van up to northern Ghana where we were getting completely away from the city, we were getting into what they called the bush, the forest, savannah. We stopped very briefly in Kumasi, which is the capital of the Ashanti kingdom, and then we went to Tamale. It was the home of the Dagomba people. We stayed there for quite a few days and that’s where we met the king prayer drummers of the Dagomba people and we began to play with them. Every day they would play in the village square and they invited us to join them. It was like a big drum circle, maybe 15 drummers playing talking drums and bass drums. We played with them in these ritual performances.

From Tamale we then took the van up to Bolgatanga. Bolgatanga was the home of the Fra Fra people and it was very interesting because there’s a 45 out right now by us with a guest star, Guy One. It’s called ‘Tinoge Ya Ta’a Ba.’ Guy One is one of the most famous Fra Fra musicians, and he plays a two-string fiddle [kologo]. But 45 years ago, before Guy One was even born, I was playing with his father, his grandfathers, the drummers, they were the Fra Fra people.

Where did you go after Ghana?

IA: We went over Uganda, then we lived in Kenya for another two months and we studied with the Massai and the Kikuyu musicians. Then we went to Ethiopia. All the time I was there I was recording African music. So while I was in Ethiopia I recorded the musicians in Lalibela. And Lalibela was the place where they had churches carved out of solid rock, King Lalibela in the 12th century. And then we came back to Young Springs, Ohio, where I graduated.

You collected a lot of instruments on your travels, but chose to play them in your own way. Was that an attempt to avoid being appropriative?

IA: We really wanted to explore in our own way. We never assumed, okay, we’re going back to Africa and we’re Africans. Africa was our ancestral home, but it wasn’t our home. Our home was where we were in America. We were proponents of a unique musical style created by African-Americans. Even today I have African instruments that I continue to play on many of my albums, and right now I love my mbira, the thumb piano from Zimbabwe, but I play them very differently from the master musician who plays mbira. So I would never assume that I was trying to play these instruments and copy how they did it in Africa, I never wanted to do that. I wanted to do it in my own original way.

So you brought these experiences back and started recording as The Pyramids.

IA: Lalibela was our first album. We were among the first wave of musicians to produce our own albums. Cecil [Taylor] was already starting to produce his own recordings; he was disenchanted with the traditional record labels. At the same time we began to produce our own albums as well. Lalibela was the first of three self-produced albums, so I always say we were DIY, before DIY came around. We recorded Lalibela on a four track, we mastered it with a friend we had in Yellow Springs, we went down to Cincinatti and we pressed up about 500 copies of the album. Then we began to distribute them. We sold them at our concerts, we sold them to friends, we sold them to family, we were selling them out of the trunks of our cars. We made enough money to order another 500 and then we did the same thing with the second album, King Of Kings.

Not too long after that, I had a brother living in San Francisco, so we decided we were going to go out to San Francisco. We recorded the third record, Birth Speed Merging, there. New members of The Pyramids joined the band, including Heshima Mark Williams [double bass], Kenneth Nash, a very well known conga player, Augusta Lee Collins [drums]. And then Kimathi came back as the second bass player.

What kind of influences were you soaking up in San Francisco?

IA: We were soaking up the music that was happening out there. Sly & The Family Stone was coming through there a lot. There was all kinds of rock music, but also Sun Ra was coming through all the time, Art Ensemble Of Chicago were coming through, so there was a lot of music happening. At the time, a lot of musicians began to play solo concerts. That was unheard of in jazz up until that time. There was this small club [in Berkeley] called Mapenzi and it specialised in solo and duet performance, like Roscoe Mitchell would come and so do a solo show, Joseph Jarman would do a solo show, Roland Young, and I did a duet with Roland Young. So it was a period for experimentation.

1977 was when the band played our last show, at the UC Berkeley Jazz Festival. We were going through our own growing pains. We were young, like 25 years old. I’d just been married – I had my daughter out there – but I went through my divorce with Margaux, everybody wanted to go our own different directions, so that was the last show. I continued to live in San Francisco, Margaux got her PhD in music in UC San Diego. I began to branch out and play the more traditional jazz. And in 1977 that’s when I founded Cultural Odyssey, the organisation that has been my foundation up to this very day.

How did the reactivation of the Pyramids come about?

IA: I was already producing my own CDs: Portraits in 1998, Centurion in 2000 and then Homage To Cuba in 2004. But around that time in 2004, there was all this additional energy happening around the internet, with people contacting me about the music of The Pyramids. I decided to do a reunion concert in 2007. [We did] the very first European tour of the reunited Pyramids in 2010, and then in 2011 we recorded at Faust studios our first album since reuniting.

When you reactivated The Pyramids, was there a conscious plan for what you were going to do or was it more spontaneous?

IA: The first tour was a combination of revisiting some of that music we made in the ‘70s and adding my new music to the repertoire. So when we recorded the album it was mostly new music. None of the music had been recorded before, so we didn’t do any of the music we had done on the previous three albums. It was pretty much all new music. But there have been a lot of changes. Sometimes the best laid plans still can go astray.

There was a somewhat parting of the ways whereby Margaux and Donald decided they would not tour. I think it had mostly to do with business decisions and the practical nature of how we were going to finance a band coming to Europe. Also, we’re all older and some of us have health issues. So we recorded Otherwordly as a quintet. Myself, Kimathi Asante, Kenneth Nash, Bradie Spellers and Kash Killion who was a new addition as a bass player. Kash had played a lot with Sun Ra, so he brought that otherworldly contingent to the band. The Pyramids now has been together longer in this new version than the original. It’s been through a series of incarnations. It’s been wonderful because it’s created whole new musical influences from the different band members who have come in and out of the band.

You’ve said that We Be All Africans is partly inspired by Fela Kuti – not so much in the music, but in terms of its message. Can you tell us more?

IA: I think this is the most contemporary version of my music. We’ve always been a socially conscious band – I call it art as social activism – and when you look at the music of Fela, when you look at the music of Bob Marley, these are musicians that refused to not say something about the times they were living in. So with the uprising that was happening in Ferguson with the killing of Michael Brown by police, and a whole line of subsequent police murders of young black African-Americans, as well as this whole immigration crisis and people wanting to build walls: Fortress Europe and everything that’s happening with Trump. The fact is that we are all human beings. Many anthropologists and archaeologists think that man began in Africa. So We Be All Africans implies that we are all one human family, we are all descended from one common ancestor. A human ancestor. Not a black ancestor, not a white ancestor. So why are police shooting on young black men, why are we preventing Africans and Syrians [from entering Europe]? We have to be much more understanding.

What can we expect from the live show?

IA: I consider this tour to be an extension of the We Be All Africans album that is really still quite fresh. But we will also have completely new music that I am preparing for an upcoming follow-up album. Bradie [Speller] will be there, an original member, Sandy [Pointdexter], the violinist, and we have three other very interesting newer members. It’s the same band as a wonderful BBC live broadcast [we did] for Late Junction.

Will there be any theatre or dance elements?

IA: Well, I’ll be tap dancing that’s for sure. I’m doing the black American tap dancing which is a very different kind of style. But yeah, we’re going to be doing our whole ritualistic, ceremonial performance. It will be very much in the tradition of The Pyramids’ live ritual.

There’s a whole new wave of musicians inspired by the spiritual jazz of The Pyramids and their peers. Are you excited by this development?

IA: I am thrilled. I am so excited. And what’s even more exciting is that I feel the Pyramids are part of it. It’s wonderful to be in the same company. We did a West Coast tour with Floating Points, who was maybe not even born when The Pyramids was founded. But him embracing our music is an honour and vice versa, I feel wonderful embracing his music. To be a part of this new movement of spiritual jazz, of Kamasi Washington and Flying Lotus, everything that’s going on, it just shows that music is really not as segregated as it once was, where it was all in these separate pockets. We have more in common than we have difference.

Idris Ackamoor & The Pyramids play as part of Dekmantel Festival’s opening concerts in Amsterdam on August 3. You can get tickets here