Many a music critic will be tell you, often at quite tedious length, about the joys of a band’s early EPs, why Sunny Sundae Smile is in fact better than Loveless, how the Buzzcocks never bettered Spiral Scratch, or why Fleet Foxes really should have called it a day after Sun Giant. When it comes to a new band, sometimes they might even stick around until the debut album before moving on to the next eager-eyed band of Telecaster-wielding cannon-fodder.

For this feature we wondered: what of the later years? The days of fading relevance, ill-advised reinventions and public apathy. The long-term fortunes of the artists we’ve listed here are varied. Some became something of a laughing stock, some retreated from commercial relevance into the realm of "cult", others simply plodded along and played the hits, sneaking the odd new track in to a setlist if a crowd seemed particularly polite.

We’re not saying, of course, that they’re necessarily these artists’ best albums. It would be foolish to claim that The Fall really bettered Hex Enduction Hour with 2015’s Sub Lingual Tablet, but what unites them all is that our writers think they’re brilliant. We asked them to pick a record that had been critically shunned or for the most part forgotten about – no Blackstar, for example – and while they didn’t have to be the writer’s absolute favourite, we wanted something for which they had a deeply held affection for. We also decided not to count artists who, in our opinion at least, have grown only better and more acclaimed with age – Scott Walker, Kate Bush, Tom Waits et al.

Patrick Clarke

If there’s some later work that you prefer, a critical fiasco you’re eager to defend or just a record that everyone ignored, please let us know in the comments below.

AC/DC – Black Ice (2008)

(Columbia)

Granted, AC/DC’s 15th album was hardly going to break any boundaries, but the supposed old adage that the band simply made a career out of churning out the same sound for close to five decades is one of rock’s most tedious, and untrue, cliches.

Although before Black Ice appeared after an eight-year hiatus in 2008 the band had seemed to have faded well into the greatest hits arena circuit, their comeback record stands among the very finest of a now 42-year discography.

What really sets Black Ice apart is its songwriting, the way Angus and Malcolm Young weave their guitars to make the most of the space lent by Phil Rudd and Cliff Williams’ driving, yet perfectly un-flashy rhythm section. Each song on Black Ice feels free, dynamic and unburdened in a way they hadn’t sounded in decades, yet never veers towards indulgence. While Brian Johnson’s vocal, while a little worn with age, is as indomitable as ever.

AC/DC’s Black Ice tour was my first proper gig. In the years since I’ve seen plenty of bands who feel obliged to slot their new material amongst the classics. With AC/DC there was no obligation; when the title track followed the classic ‘Thunderstruck’, there was no drop in the atmosphere, no polite headbangs as the crowd waited for another classic. As far as we were concerned, this already was one.

Patrick Clarke

Alice In Chains – Black Gives Way To Blue (2009)

(Capitol)

Many diehard Alice In Chains fans will tell you that by reforming the group with new singer William Duvall, guitarist Jerry Cantrell might as well have teabagged Layne Staley’s grave. But from its inception the band had been Cantrell’s vision: he wrote nearly all of the band’s music, most of the lyrics and contributed his essential backing vocals to nearly every song. He even sang lead for most of 1995’s Alice In Chains while Staley fought the crippling heroin addiction that eventually claimed his life.

On Black Gives Way To Blue, released seven years after that tragedy, Cantrell never seeks to turn the page on the band’s harrowing past and songs like ‘Your Decision’ and the haunting title track (oddly featuring Elton John) heart-wrenchingly convey black grief at the loss of a friend. It’s not all darkness though, full pelt rockers like ‘Check My Brain’ and ‘A Looking In View’ are the first opportunities for the band to truly wig out since 1992’s Dirt. There’s a lightness of touch to the return which makes it easier to stomach. Mike Inez and Shaun Kinney’s returning rhythm section is tightly screwed in place and Cantrell wisely transitions to frontman, leaving an unobtrusive Duvall to fill the guitar and vocal gaps.

Josh Gray

The Beach Boys – Keepin’ the Summer Alive (1980)

(Brother/Caribou)

There’s a potential irony to this album’s title track, with its "Try’na keep the summer aliiive" refrain. We’re here at the arse-end of the Beach Boys’ career, and yet here they are: cousins, friends and brothers; depicted in a snowglobe, playing together just as they would at Knebworth the same year.

But this snowglobe contains sand, sea and surf while outside has grown cold and icy. It echoes their 1971 album, ‘Surf’s Up’, itself a strangely defeatist declaration of a title. There’s a bit of generic late-70s surf-pop to hack through before you get to the good stuff. That said, ‘Livin’ With a Heartache’ is notable as a solo single sung by Carl Wilson with few backing harmonies.

By side B we’re firing on all cylinders, with four Brian Wilson numbers and Bruce Johnston’s lovely closer, ‘Endless Harmony’. Some of the stronger songs were written years prior, but ‘Goin’ On’ with its powerful Queen-like harmonies, is a proper, heartfelt belter. After a spree of patchy (to be kind) albums through the late 70s, Keepin’ the Summer Alive does what it says on the tin, however ephemerally. The last truly essential Beach Boys album.

Charlie Frame

Frank Black & The Catholics – Show Me Your Tears (2003)

(Cooking Vinyl)

Because of its timing, this album was overshadowed by Pixies to an even greater extent than every other Frank Black & The Catholics record. It was promoted amid rumours that they were on the cusp of reforming, as indeed they did; the announcement arriving shortly after Show Me Your Tears’ release. Unlike Black’s first and most famous band who fizzled out with Trompe Le Monde, The Catholics went out on a high. The album’s subsequent tracks are more laidback than the sleazy stomp of opener ‘Nadine’ but there isn’t a bad apple among them as The Catholics rattle through their own oddball variations on alt-country, honky tonk and classic rock, while their habit of recording straight to two-track provides a live, urgent feel to even its most downbeat numbers. Whereas Pixies peddled exotic tales of incest, prostitutes, space aliens and dead primates, here Black’s lyrics were informed by the collapse of his marriage and recurring themes include fleeing, drinking and plunging into oblivion. It’s not all doom and gloom thanks to the jaunty pedal steel on ‘Goodbye Lorraine’, for instance, and the moments when Black speaks of liberation: "It’s a beautiful day / No, it’s horrible day / And for the first time in my life I just don’t care".JR Moores

Can – Saw Delight (1977)

(Harvest/Virgin)

Released just five years after Ege Bamyasi, some might protest that Saw Delight isn’t exactly ‘late period’ work. But for many fans, Can’s imperial phase ends with the departure of Damo Suzuki in 1973, and after that, their music becomes less boundary-pushing/worthy of investigation. However, this is a serious error, and certainly one I’ve made in the past. By integrating funk, disco and ‘world’ influences into their avant rock template, and pioneering the use of ‘found sounds’, post-Damo Can are arguably even more ahead of the curve than their earlier incarnation.

There’s a significant change of personnel on Saw Delight: bassist Rosko Gee and percussionist Rebop Kwaku Baah (both formerly with Traffic) join the band, while Holger Czukay adopts a proto-sampling role, experimenting with tapes and shortwave radio broadcasts. Here’s an excellent clip of them performing the album’s opening track ‘Don’t Say No’, which lifts the riff from ‘Moonshake’ but takes it somewhere both funkier and stranger, with Czukay in full-on mad professor mode. ‘Call Me’ is aqueous and ecstatic in equal measure, all driving low-end and bright splinters of guitar, while ‘Fly By Night’ is charmingly skewed Euro pop that’s decidedly Bowie-ish. But it’s the futuristic Afro-jazz of ‘Animal Waves’ that’s the mesmeric centrepiece: spacey ambient synth washes give way to Michael Karoli’s gypsy violin weaving like a drunken spirit in the night, before Baah and Jaki Liebezeit commence an extended congas vs snares duel over Gee’s convulsive bassline. It arcs, dips and rises, and when Czukay drops the cut-up voices of Arabic and Indian folk singers into the mix, it strongly anticipates Eno & Byrne’s My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts.

Joe Banks

Captain Beefheart And The Magic Band – Bluejeans & Moonbeams (1974)

"The camel wore a nightie … in the party of special things to do …" As opening lines go, it’s a killer, but it wasn’t enough to prevent Captain Beefheart from describing his ninth album – recorded, after the Magic Band’s departure that spring, with what was soon nicknamed the ‘Tragic Band’ – as "horrible and vulgar". Indeed, for fans of his knotty experimentalism, its smooth accessibility was deeply unsatisfying, even unsettling. Shorn of this context, however, Bluejeans… offers gloriously laidback grooves saturated with an unabashed sentimentality. Even its weakest tracks – the harmonica-drenched, proto-Supertramp stomp of ‘Captain’s Holiday’, the Laurel Canyon, country-rock of ‘Twist Ah Luck’ – would still draw gasps were they lovingly, anonymously, reissued by, say, Light In The Attic.

But Bluejeans…‘s peaks are breath-taking, and despite Van Vliet’s affectionate, melancholy rasp, it’s the polished work of his derided session musicians that towers highest: the title track’s guitar and keyboard solos, the surreal limp of opener ‘Party Of Special Things To Do’, the Tom Waitsian cover of J.J. Cale’s ‘Same Old Blues’, ‘Observatory Crest”s extended instrumental. The highlight is ‘Further Than We’ve Gone”s bluesy guitar solo, whose passion escalates, over a descending series of piano chords, towards Van Vliet’s prophetic declaration: "Further than we’ve gone/ The stars sing a song/ Together/ That only lovers can hear". Plenty felt Bluejeans… went numerous steps too far, and the Captain later, famously, advised listeners to return their copy, along with its immediate predecessor, Unconditionally Guaranteed, to record stores. I, though – like, apparently, Kate Bush – treasure mine. Trout Mask Replica meanwhile gathers dust.

Wyndham Wallace

I’ve been listening to LPs by the Bad Seeds pretty much on the week of release since the first one, From Her To Eternity in 1984. However, out of all of them I listened to 2013’s Push The Sky Away more than any of the others. In fact, once in my possession it was barely off the turntable for several months. Now, there is a chance this says more about the disagreeable age and phase of life I now find myself in rather than the outstanding quality of the album but it’s my job to try and convince you I have some kind of authoritative and objective sense about these things, so here goes…

I have come to think of Push The Sky Away as Nick Cave’s most fully realised album. (A close second would be Grinderman. The first album by the project that rejuvenated and galvanised Cave was typified by the generation and then discharge of a great amount of energy, clearing the psychic decks in order for Push The Sky Away to work.) Only an idiot would deny the swaggering magnificence of the Bad Seeds’ initial bloody trio of LPs. But after switching the rancorous junkyard blitz of The Birthday Party for a new direction, initially the Bad Seeds sounded like a mythical animal constructed of broken orchestra instruments, dragging itself painfully along the road to Hell. Despite flashes of utter brilliance in ‘Tupelo’, ‘The Singer’ and ‘Saint Huck’, they remained a band trying on new clothes for size. After it turned out these new clothes fitted just fine, there were plenty of other brilliant albums along the way (Tender Prey, Murder Ballads, Let Love In) but none quite hit it like the first album they completed without Mick Harvey.

Some might say it has no real all-time great single and I would agree. But it is probably because there is no barnstorming ‘Red Right Hand’, no ‘Dig, Lazarus, Dig!!!’, no ‘Get Ready For Love’, that the album works so well. Every piece fits perfectly into the whole without one specific song clamouring for attention. And yet, ‘Jubilee Street’ is one of Cave’s best songs to date. It opens in a disarmingly minimalist fashion, just to swell to grand psychedelic proportions as Cave’s vision takes flight like one of Thomas De Quincy’s fever dreams: “I got a foetus… on a leash! I am alone now. I am beyond recriminations. The curtains are shut, the furniture is gone. I’m transforming. I’m vibrating. I’m glowing. I’m flying… look at me now.” All as Jean-Claude Vannier and a million screeching bats taking flight at sunset bring us to the glorious conclusion.

He knows how good he’s gotten as a writer, so he can have fun at the expense of his own image and what his fans expect from him. ‘Jubilee Street’ is followed immediately by ‘Mermaids’ which appalled some with it’s opening lines of “She was a catch. We were a match. I was the match that fired up her snatch…” But then how should a 2017 reworking of ‘The Love Song Of J. Alfred Prufrock’ begin? Cave has developed his own version of classic style, so naturally everything reads as easy as hell, like these words just flowed from him in one sitting, jotted down on the back of a beer mat. But mastery of a classic style means no one needs to consider how hard won these lyrics actually were. The proof isn’t always in the pudding but I would suggest in this case there is a very good reason why Nick Cave And The Bad Seeds are bigger now than they ever have been in the past. Check those chart placings, check the size of those arenas – it’s clear to me that after 37 years they’re still travelling on an upwards trajectory.

John Doran

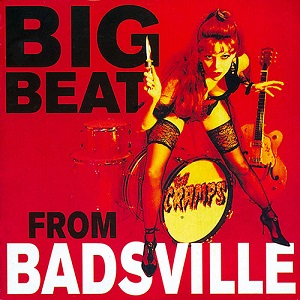

The Cramps – Big Beat From Badsville (1998)

(Epitaph)

There’s a school of thought that subscribes to the theory that The Cramps, those high priests of deviant psychobilly, went off the boil the moment they decided to change one of their twin guitars for a bass. True, their material varies in quality from that point onwards but only really after the later departure of drummer Nick Knox, the band’s under-rated secret weapon.

So it was that the limp one-two of 1991’s Look Ma, No Head! and its follow-up, Flame Job, three years later, suggested that the band would be, from that point on, best sampled live. Yet 1997’s Big Beat From Badsville was a swing back in the direction of the gloriously demented Stay Sick! and claimed a vital goal deep in the second half of the band’s career.

Admittedly, The Cramps’ reduction to single entendres grate a little here (see ‘Wet Nightmare’ or ‘It Thing Hard-On’ for evidence), but it’s hard to argue against full-tilt rockers such as ‘Cramp Stomp’ and ‘Devil Behind That Bush’ when they’re played with such conviction. Or even resist a knowing smirk on their paean to S&M, ‘Queen Of Pain’, when Lux ascertains that "those marks will be hard to explain."

Add in Lux and Ivy’s muscular production with an album made up of fourteen original songs and no covers, Big Beat From Badsville proves that The Cramps’ healthy obsession with kinky sex, drugs, and rock’n’roll could still yield hedonistic results late in the day. Which is usually the best time for all of that anyway.

Julian Marszalek

Dinosaur Jr. – I Bet On Sky (2012)

(PIAS)

I Bet On Sky was the third album released since the seemingly unlikely reunion of acrimonious Dinosaur members J Mascis, Lou Barlow and Murph and matched the three album output of the late 80s/early 90s original line-up. If 2007’s Beyond proved they could still play together and that J could abide Lou and his writing input and the 2009 album Farm augmented a repertoire they could happily profit from live, I Bet On Sky was the first time that potential clouds had cleared and a confident future could be predicted. J’s languid drawl and mangled guitar is still front and centre, but the sound is much more expansive, with clear space between it and a much more sympathetic mix for Lou’s bass and clarity for Murph’s drumming that even verges on liberated and joyous, with cowbells and cajons on ‘I Know It So Well’.

The album kicks off with a barnstormer, as is seemingly Dinosaur Jr. tradition. Like the ubiquitous ‘Freak Scene’ on Bug or the Mascis-only era classic ‘The Wagon’ on Green Mind, ‘Don’t Pretend You Didn’t Know’ captures in a moonshine bottle the very essence of the band, except for me it transcends that spirit with a rare and plaintive yet soaring piano line. Purists need not worry though as there is still plenty of majestic shredding on ‘Watch The Corners’ and if to prove the growing confidence of a band happy with itself J even sounds like he might allow himself to be chipper on ‘Almost Fare’ and he is almost fair with Lou as he’s allowed him a couple of trademark forays. ‘Rude’ is the equal of Sebadoh pop nugget ‘Ocean’ and ‘Recognition’ is reminiscent of the best of Barlow’s Bubble & Scrape introspections.

It turns out that Dinosaur Jr. is now happily divided and as J admits with the titular lyric "I bet on sky" in the driving Deep Wound nodding, cumulonimbus busting ‘Pierce The Morning Rain’, there’s room for some blue-sky thinking with a reformed line-up you’d have confidently bet against.

Nick Hutchings

Einstürzende Neubauten – Lament (2014)

(Sire)

Einstürzende Neubauten are a band dogged by clichés of drills, thrills and sneering remarks about angry Germans. The ignorant are fools, of course, for this is a group who’ve taken their jet compressors and plastic piping percussion on an eloquent, graceful wander through the autumn light. These tools became the very stuff of Lament and its accompanying live show, for example with beats appearing and then vanishing from rhythms to symbolise countries coming in and out of the conflict. Blixa Bargeld’s lyricism here is among his finest work, based on intensive research among archives and books but also of wax cylinder recordings of old soldier’s songs from the time. While Lament was originally conceived for a commission to perform at Diksmuide on the pockmarked battlefields of WWI’s Western Front, the subsequent tour took on its life of its own, becoming a fitting commemoration for the lives lost.

Luke Turner

The Fall – Sub Lingual Tablet (2015)

(Cherry Red)

The best albums by The Fall inhabit their own strange eco system. Sub Lingual Tablet certainly does, referencing the oddness and banality of the digital life. ‘Pledge!’ is centered around the peculiar, biblical tone the word has taken in recent years, invading life at all corners (‘and the workers ask Nellie for money. She says ‘And Pledge! Pledge! Pledge!’). Elsewhere ‘Facebook Troll’ and ‘Quit iPhone’ hold mirrors to grotesque self obsession. ‘Venice with the Girls’ is straggling dynamism, a screwed ear worm. Musically, it’s hard circular grooves: banging, tight, any thought of ponderous jangle banished in favor of a disciplined and unrelenting rhythmic bent. Smith’s ferocious speed ravaged gurgle is pushed perversely high in the mix. An intake of breath becomes a stab; phlegmy cough a percussive device. Savage and vital.

Harry Sword

Front 242 – 05:22:09:12 Off (1993)

(Epic/Red Rhino)

‘I got into this one first’ is the universally accepted excuse for liking the uncool album the most. But when it’s an uncool album released in 1993 by a seminal industrial act who’d been at the peak of their powers in the late 80s people still try to tell you you’ve got it wrong.

My entry point into Front 242 was their dual 1993 albums 06:21:03:11 Up Evil and 05:22:09:12 Off. The albums – on repeat – corresponded with my first real boyfriend and are irretrievably knotted up in a heady tangle of awakening. Off, particularly, grabbed hold and never let go – not because it’s the better of the two (it’s not) but because of three key songs and its sense of femininity and sexuality.

I grew to love orthodox 242 classics such as Front By Front and Official Version. And if I’d been a fan in the 80s, I can see that the band’s departure from minimalism and incorporationof emotive vocals and techno and even trance tropes might’ve been disappointing.

But I loved the screams and sinister story of ‘Serial Killers Don’t Kill Their Girlfriend’ as well as its ambient outro. The build and release on ‘Junkdrome’ united my raver and industrial friends in a froth of dancing – and still gives me goosebumps. Most of all, though, it was Kristin Lee Kowalski’s sultry hisses on ‘Crushed (Obscene) ‘, backed by that monstrous rubbery drum. "This heavy heart that I carry / Still holds the weight of you. "

Kate Hennessy

Emmylou Harris – Stumble Into Grace (2003)

(Nonesuch)

The popular view has it that Emmylou Harris’s middle-aged renaissance had its apex with 1995’s Wrecking Ball and to a lesser extent 2001’s Red Dirt Girl. Stumble Into Grace (2003), which does retain the effortlessly sensual mood of those records, is better than both. Its eclectic sonic quirks moved her firmly toward a sophisticated kind of pop and away from any variation on country while, more crucially, there is a sombre sexuality in this record that makes these songs, all of which express her particular brand of vulnerable intimacy, compelling in their melancholy.

Harris, of course, discovered songwriting late in life, with this album almost entirely dominated by her own compositions – most notably the dream-pop finesse of the beautifully unhurried opener ‘Here I Am’, and ‘O Evangeline’, which bears the heavy influence of the McGarrigle sisters, who collaborated with Harris on three other tracks here.

Stumble Into Grace dwarfs anything from her 1970s heyday for both profundity and even passion. Harris should be remembered for her output between 1995 and 2005 more than Pieces of the Sky, Blue Kentucky Girl or anything to do with Gram Parsons.

Barnaby Smith

Heart – Jupiter’s Darling (2004)

(Eagle)

Heart have never and will never best their 1976 debut Dreamboat Annie, a record that took the already formidable hard rock/folk template of Led Zeppelin 3 and pushed it to new heights of ingenuity. But the Wilson sisters, never critically adored by the sexist 70’s music press, still rarely seem to command the respect due such an influential act who continue to create and evolve nearly 40 years later.

Admittedly they lost their way for a while in the 80s with power ballad-packed dross like Heart and Bad Animals, and I’m sure even the band would agree that every copy of A Lovermongers’ Christmas should be tracked down and destroyed. But late Heart largely means great Heart. The grunge movement that briefly elevated their hometown of Seattle to musical capital of the world reignited Nancy Wilson’s passion for guitars, and their very much requited love for Alice In Chains invigorated their output for the next 20 years. Old collaborator Layne Staley’s influence on Ann Wilson’s impassioned vocals is evident on ‘Enough’ while Jerry Cantrell himself contributes a steady guitar chug to ‘Fallen Ones’. ‘Oldest Story In The World’ also invented the template for every Alter Bridge chorus ever, demonstrating Heart’s undimmed ability to inspire.

Josh Gray

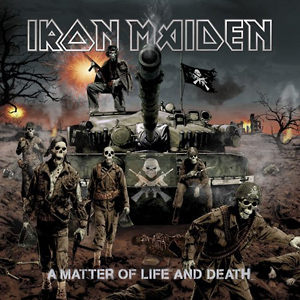

Iron Maiden – A Matter Of Life And Death (2006)

(EMI)

A strange thing about late-period (i.e. post-2000) Maiden. It’s simultaneously bigger and more preposterously grandiose than any of their 1980’s ‘classic’ material – but also rawer and heavier. A Matter Of Life And Death is the greatest of the late period records (to this writers’ ears, their greatest record full stop) for a number of reasons. Firstly, it finds Maiden at their most progressive – soaring epics like ‘Brighter Than a Thousand Sons’ would suit the war room at Valhalla- but bolstered by an untethered maniacal force. A loose concept album (the concept? ‘War’: all the songs are about ‘War’) Dickinson soars ever upwards, living every word of ludicrous derring do, turning puce with the maniacal energy required to belt out these strapping paeans to horror, adventure, wasted youth. Mostly using the first takes, on hearing it back Steve Harris refused even to have it mastered – a situation unheard of, when talking about a band of Maiden’s size. The result? A galloping charge into bloody glory, a display of peerless technical force only without any of the sheen. True combat rock.

Harry Sword

The Jesus And Mary Chain – Munki (1997)

(Sub Pop)

With all the column inches and radio play garnered by Damage And Joy, the Reid brothers’ first album in 19 years, it’s amazing to think of the air of indifference that greeted their sixth – and what was to be their then-final – album, Munki. Indeed, if any one album displays the vagaries of the music business and fashion tastes, then this record is it.

Seemingly dropped like an unwanted fart during the hangover of the Britpop years, the band’s label, Warner’s, wafted the album away and released The Jesus And Mary Chain from their contract. Despite being rescued by Alan McGee and returning to their Creation Records roots, Munki was still ignored, probably thanks to the Reids being mad with each other rather than being mad for it.

A shame because the passing of time has come to reveal Munki as the album to follow Psychocandy in their back catalogue’s pecking order. A sprawling double album recorded under circumstances that could be politely described as "tense" – Jim and William recorded their songs separately from each other – Munki is a surprisingly coherent yet diverse work that encompasses their entire career while still sounding fresh. Feedback, electronics, ballads and more are all present and correct and in closing number ‘I Hate Rock’n’Roll’ you have their single most extreme and bonkers track ever. What’s not to like?

Julian Marszalek

Killing Joke – Killing Joke (2003)

(Zuma)

Releasing a second self-titled album 25 years after the first says a lot about rebirth, reinvention, self-realisation – about becoming what you were always meant to be. While there’s plenty to love in the ten albums that preceded this one, KJ2003 is where everything came together in one furious package. The production job by Gang of Four’s Andy Gill is a major reason why. Taking elements of KJ’s early lo-fi post-punk sound, their ’80s sheen, early ’90s dirty extremities and their dabblings in industrial, Gill arrives at an almost cartoonishly bellicose new aesthetic for KJ – vast, immediate, ferocious, spacious and thoroughly bloody metal. The songs more than justify the visceral attack, full of focused paranoia, rage, revolution, conspiracy, ritual and eschatonic nihilism.

Perhaps surprisingly, the secret weapon here is Dave Grohl. Regardless of your opinion of his nice-guy stadium rock schtick, Grohl is a fearsome drummer. Here, like with Queens of the Stone Age’s Songs for the Deaf, Grohl acts a lightning rod, channelling the band’s sometimes sprawling, chaotic energy into something remarkably focused, urgent and powerful. Nowhere is his contribution more evident than in ‘Asteroid’ – a song already seemingly at terminal velocity, which kicks up into apocalyptic gear in its closing bars.

Matt Evans

King Crimson – The ConstruKction Of Light (2000)

(Virgin)

There are many reasons not to like this album. The processed electro-drum sound. Adrian Belew’s wince-inducing lyrics about Prozac and extra-terrestrial penises. That embarrassingly gimmicky misspelling in the title. And yet, for those of us who prefer Crimson in heavy and technical mode, this is their most consistent release. While In The Court …, Larks’ Tongues…, Discipline and Red are all better known and have more well-known tunes, they are also highly uneven – for every thrilling riff-fest, there’s some interminable noodling or an unbearably treacly faux-medieval folk ballad. Crimson have always been a fiendishly clever band, but nuance and emotion are not their core strengths.

ConstruKction‘s focus here is on dry metal bite and geometrical brain-scrub, often employing a mind-boggling ping-pong technique in which Belew and Fripp map out a complex syncopated melody by playing alternate notes at either end of the stereo field. The ‘stupid puny meatbags and your pathetic feelings’ aesthetic reaches its apex in Robert Fripp’s solos in ‘FraKctured’ and ‘Larks’ Tongues in Aspic Part IV’. While many virtuoso guitarists try to soften their egotism by cynically injecting soul, but Fripp has no time for such, err, fripperies. Instead, his solos are nothing but exercises in playing really difficult scales really fast and really repetitively – more Orthrelm than Satriani.

Where Crimson excel is unfeasibly complicated heavy math-prog devised by artificial intelligence and played by androids. ConstruKction is them at their most mechanical, relentless, inhuman and impossible, and therefore at their best.

Matt Evans

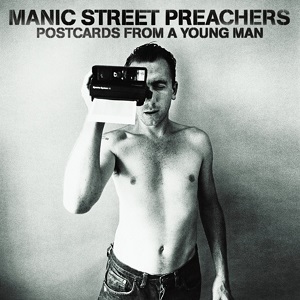

Manic Street Preachers – Postcards From A Young Man (2010)

(Columbia)

If one discounts the obvious pre/post Richey divide, the multifaceted career of the Manic Street Preachers can be split into two distinct periods: before, and after, 2007’s leviathan comeback record Send Away The Tigers. That album saw the Manics reborn as critics darlings, and their experimentation, whether with kraut and industrial on Futurology or the wistful acoustic melancholy of Rewind The Film were lent a sense of newfound legitimacy by their new role as genre-hopping polymaths.

Postcards From A Young Man feels like the forgotten book of the Manics’ New Testament, as bold, brash, and straight-up pop as they’ve ever gone, with Nicky Wire proclaiming it as their last big shot at mainstream appeal. It feels brushed under the carpet, an ill-advised grasp at the arenas that didn’t fit the band’s more astute new guise.

Like Generation Terrorists before it the album fell short of the impossible goals set for it by its creators, but buried away on Postcards are some of the band’s greatest songs. The title track in particular has them recapture the same heady blend of indulgent arena rock and crushing romance that spawned ‘Motorcycle Emptiness’, while James Dean Bradfield’s sweeping duet with Ian McCulloch on ‘Some Kind Of Nothingness’ puts ‘Your Love Alone’ to shame.

It might lack the eclecticism of Futurology and the nuance of Rewind The Film, but Postcards… makes up for that and then some with a self-indulgent, string-soaked sweep of emotive, politicised arena-pop. It’s glorious, and exactly what the Manics have always done best.

Patrick Clarke

Joni Mitchell – Chalk Mark In a Rain Storm (1988)

(Geffen)

Chalk Mark could well be the high-water mark of the glossy pop sound Joni Mitchell had arrived at by the Eighties, coating her deft lyrics in high-production sheen. Opener ‘My Secret Place’ is a case in point: a duet with Peter Gabriel (one of a cast of guests including Willie Nelson, Tom Petty and Wendy Melvoin and Lisa Coleman of Prince’s Revolution), the song, depicting a couple on "the threshold of intimacy", as she called it, flexes her knack for worldly-wise aphorisms ("People talk to tell you something, or to take up space"), but hangs around a minimalist keyboard motif underpinned by Manu Katché’s urgent drumming. Mitchell and Larry Klein’s reverb-heavy production gives the album a feeling of wide-open spaciousness, siting it in the desert landscape that rolls away behind her on the cover. Time might have been less kind to Steve Stevens’s rawk riffs and Billy Idol’s rawkier vocals on ‘Dancin’ Clown’, but the album’s highlights – ‘Lakota’, an ecocentric protest song arguing against the destruction of Native American lands in Arizona’s Black Hills, and ‘Cool Water’, a rewrite of the country singer Bob Nolan’s 1936 original to take aim at environmental pollution – have lost nothing.

Laurie Tuffrey

Fighting the corner for Mogwai’s 2008 effort The Hawk Is Howling might seem counter-intuitive given that members of the band have admitted to not liking it anymore either. Upon release it was critically discarded like a used handkerchief, with Pitchfork’s review describing it as "redundant and tenuous".

The band’s sixth LP stuck unapologetically to tropes that defined the releases that preceded it but goddamnit it still boasts some of their most acutely realised material to date. The arrogant heft of ‘Batcat’ and ‘The Precipice’ alone boasts a satisfying brutality that still leads to chest quakes and gritted teeth.

From the conscientious dynamic climb of ‘I’m Jim Morrison I’m Dead’ to the reposeful keys and languid guitars of ‘Thank You Space Expert’, the album is full of understated highlights of the band’s catalogue. ‘Local Authority’ is the aural equivalent of a hot towel while ‘I Love You, I’m Going To Blow Up Your School’ is a tempered beast of cinematic scope with a magnificently chaotic, if brief, peak.

While compared to earlier triumphs it maybe feels a bit by-the-numbers, but The Hawk Is Howling is nonetheless a no-bullshit package of quality cuts from a band who from that point on were hot on the course to becoming one of the most sought after groups of their ilk in the world.

Eoin Murray

Mudhoney – The Lucky Ones (2008)

(Sub Pop)

Mudhoney have always had a epoch defining ear for a tune, but it’s the erudite lyrics of The Lucky Ones that makes this one I have returned to many times. A master class in self-effacement, on one hand Mark Arm’s tongue is in his cheek with opener ‘I’m Now’ on the other, the band have come to terms with their place in the rock cannon and having gone from The Stooges meets The Sonics to more cosmic material, they’re ready to launch another proto-punk projectile into the ether and make no bones about it.

"The lucky ones may have already gone down, the lucky ones are lucky they’re not around" is a sad epitaph to fallen Seattle warriors, and yet nobody could have predicted that scene forefathers would have outlasted them all, not least Mudhoney themselves.

Arm may well be still packing records in the Sub Pop mail room, but not many of the records he despatches will match Mudhoney’s lasting worth, or humble sense of fun. The line "The open mind is an empty mind so I keep mine closed" on ‘The Open Mind’ is playful self parody as this is a band that knows where it comes from and is happy to doff its hat to it, however eclectic the influence, be it on ‘And The Shimmering Light’ with its Alice Coltrane/Pharoah Sanders nods or on the more explicit tribute ‘Tales of Terror’ to the Sacramento punk band of the same name.

But for me nothing beats the use of an emasculated mollusc as simile for someone who’s crazy in love, "In my fucked up gestalt, I’m a slug in salt losing it skin" in modern Mudhoney classic ‘Inside Out Over You’. They may be sick but you can’t touch lyrics like that.

Nick Hutchings

Gary Numan – Dead Son Rising (2011)

(Mortal)

Gary Numan will forever be known for The Pleasure Principle (an album so forward-thinking it began and ended the 80s in 1979), Telekon and Tubeway Army’s Replicas. On those records he perfected a sound he would spent the rest of his career trying to escape, begrudgingly keeping ‘Are Friends Electric’ and ‘Cars’ in his set in order to avoid a likely lynching.

But outside of this holy electronic trinity the Thinner Whiter Duke released a number of brilliant records. The best of these he recorded as a born again industrial music devotee after falling in love with the similarly machine-like noise of Nine Inch Nails. Exile is great, as is Pure, but it’s on 2011’s Dead Son Rising that Numan really rewired the genre’s piston-powered brutality and made it his own.

There’s a newly cinematic element to tracks like ‘Resurrection’ and ‘The Fall’ that Numan’s early career work never particularly exhibited. At the same time his distinctive Moog sound is given leave to slink back into ‘For The Rest Of My Life’ as if it had never left, signalling a softening in attitude towards his own legacy that would eventually result in him embarking on a string of Classic Album shows of his own volition.

Josh Gray

Given that Neil Tennant himself came up with the narrative that pop groups have an ‘imperial phase’ of their peak operation before a commercial decline, it’s interesting that 2013 album Electric stands up with the glorious 80s years of Please and Actually. It’s as if the Roman Empire had suddenly rocked back up to Hadrian’s Wall in 999 AD sporting haut-couture jerkins. Electric‘s secret weapon is producer Stuart Price who souped everything up to the nth degree to make this a smart, sexy, joyous album that just sounds so solid compared to the output of most returning synth pop veterans. Best of all of course is ‘Love Is A Bourgeois Construct’ which borrows from Henry Purcell via Michael Nyman and has that wonderful lyric about taking tea like Tony Benn.

Luke Turner

Pink Floyd – A Momentary Lapse Of Reason (1987)

(Columbia)

Think of A Momentary Lapse Of Reason as an approprirate title. It’s not that I rate this higher than The Dark Side Of The Moon or The Wall, but this was my introduction to Pink Floyd, my gateway drug. It bridged the gap between the awful pop music I was (probably) listening to at the time, and my untapped urge to explore progressive rock and all its infinite goodness. Whilst this album was, almost entirely, a Dave Gilmour solo album by everything but name, it harked back to their music orientated beginnings, before Roger Waters took control and Floyd became a vehicle for his spite. MLoR has sprawling ambient intros, Phil Manzanera hooks, digital processed vocal segues and unforgettable artwork. It’s far too easy to say the production is a bit drab. Or that it sounds a bit like U2. Or that it’s not a proper Floyd album. But, for me, it provided a touch point to great wonders beyond, and proved that Pink Floyd could still exist without Waters’ excessive controlling hand.

Rich Hughes

Iggy Pop – Préliminaires (2009)

(EMI)

We all know the half-naked cartoon character, monkeying around to an extended rendition of ‘Lust For Life’ as the crowd goes nuts. He’s the dude who pays the bills. Another, different Iggy Pop is the gentleman you’ll find sipping vintage red wine on the French Riviera while a crackly old jazz record rotates on the turntable. Even though it’s a concept album based on The Possibility Of An Island by Michel Houellebecq, Préliminaires provides a rare glimpse of the real person behind "Iggy Pop", so much so that it might as well have his given name printed on its sleeve: Préliminaires by James Newell Osterberg, Jr. That’d also warn Stooges nostalgists who arrive expecting primal rock ‘n’ roll only to be confounded by a pensioner crooning in French or channelling the voodoo vaudeville of Tom Waits backed by acoustic guitars, keyboards, conga drums and New Orleans brass parts. Only ‘Nice To Be Dead’ approaches the heavier garage sound of The Stooges and it also has the audacity to celebrate death as a desired escape from "the ugly sounds of life." Houellebecq’s protagonist is a controversial and hedonistic comedian who’s grown bored and disillusioned with his own act. You can see why the novel made such an impact on someone who has long played The Idiot.

JR Moores

Public Enemy – How You Sell Soul To A Soulless People Who Sold Their Soul? (2007)

(Slam Jamz)

The conventional wisdom that Public Enemy fell off in the 1990s has never stood up to objective scrutiny. They may not release an album that will topple …Nation of Millions… or Fear of a Black Planet from their perches in the GoAT lists, but those who ignore PE’s post-Def Jam work are missing out.

It couldn’t duplicate the counter-cultural impact of late-’80s PE, but How You Sell Soul… is the work of a band possessed of the critical self-awareness necessary to turn two decades’ experience into vital, urgent and inspirational art. Against a lush, muscular production – the majority of which comes from Gary G-Wiz, who’d done the heavy lifting on Apocalypse ’91 – Chuck D trains his fire on a culture that had lost its way. "At the age I am, if I can’t teach/I shouldn’t even open up my mouth to begin to speak," he snarls at the heart of an album that lasers in on the hip-hop generation’s failure to grow from petulant adolescence to mature adulthood, and attacks artists who won’t take responsibility for how what they say affects their audience.

‘Harder Than You Think’ – which would become the band’s biggest UK hit after Channel 4 used is as the theme for Paralympics coverage in 2012 – argues that a sense of social responsibility is more important than studied rebelliousness. The bittersweet, genuinely moving ‘Long and Whining Road’ finds a reflective, wry Chuck telling the PE story through classic rock and pop references. And the Redman-produced ‘Can You Hear Me Now’ has a lyric that ought to be carved on the heart of every rap fan: a song about growing up without selling out that stands as one of the very best things the original prophets of rage have ever done.

Angus Batey

Pulp – We Love Life (2001)

When Pulp bowed out of their reunion tour in a homecoming show in Sheffield back in 2012 they played a career-spanning set that was not only driven by their greatest hits but also scattered with unearthed gems, with tracks such as overlooked disco stomper ‘Countdown’ getting an outing alongside their gloriously intimate sex anthem ‘Sheffield: Sex City’. Yet out of the 25 songs played only one came from their final, Scott Walker-produced album, We Love Life. It’s not their finest album but it’s a record that feels so hidden in the shadows of the Pulp discography that it borders on the forgotten altogether and it’s deserving of more. The album works so beautifully as a parting statement because it’s almost a bookended mirror of a record.

As Pulp were coming to an end, falling apart somewhat, they resembled much of their beginning period: at a bit of a loss, lacking a distinctive sense of personality, slightly muddled, ultimately patchy but with flashes of brilliance and innovation – as demonstrated on the wonderfully wonky ‘Weeds II (Origin of the Species)’ or the joyous ‘Bad Cover Version’ – and a confused and patchy Pulp is always more interesting than most.

Daniel Dylan Wray

Queens Of The Stone Age – Era Vulgaris (2007)

(Interscope)

Popular opinion labelled Songs For The Deaf the peak for Queens Of The Stone Age with Lullabies To Paralyze deemed a slide from that high place. Homme called it a ‘firewalk’ making Era Vulgaris the beast to emerge on the other side. The critic’s least favourite, the record marked a new era for the band; spiting, growling, clawing and scraping at the regulated, melodious chants of the past.

Homme knows better than trying to preserve success by playing it safe; Era Vulgaris was his way of keeping everyone in line. Ironic, playful, aggressive and dynamic takes you on a complete journey. From the slow, burn and hypnotic beat of ‘Turnin’ On The Screw’ and the grating and fevered aggression of ‘Battery Acid’, to the facetiously foxy ‘I’m Designer’ the records winds you down with the melancholia of ‘Suture Up Your Future’ giving you deep, sombre and cynical closure.

Chaotic and flirtatious, sumptuous and undignified; Era Vulgaris remains one of the finest and most misinterpreted albums from a band that will not be defined by expectations. Homme wants you to know, with the subtlety of a sledgehammer, that you’re not the boss of him.

Lara Cetinich Cory

R.E.M. – Up (1998)

(Warner)

When Bill Berry left R.E.M. in 1996, the story goes, he left them without a heartbeat, without blood, searching for another pulse. The album Michael Stipe, Peter Buck and Mike Mills released after his departure, Up, is the sound of three friends launching themselves into a new world, like nervous space explorers. And after the first four tracks, which see them trying to shrug off their selves (persist with these, or just jump straight to track 5), they find an incredibly beautiful, fragile new soul.

An unexpected, Brian Eno-Ambient Music atmosphere waves and drifts throughout this recorded, turning small, gentle moments into unexpectedly touching shapes. There’s the analogue synthesiser sounds that bring The Apologist’s sorrow softly to a close, the green, gentle melody that haunts Why Not Smile (with this brilliant, delicate line in its middle: "I feel like a cartoon brick wall"), and the longing strings that turn You’re In The Air’s feelings of desire and confusion around and upside-down, as desire and confusion are wont to do ("brighten the stars/the weather is lifting the heavens/a love like this, it’s pulling … I want you naked/I want you wild"). There is the hit of sex through this record and the deepest, hardest yearnings, but also the need to furl in, be cosseted, be held.

Michael Stipe’s voice has never sounding so beseeching either, so lost, so otherworldly, so tender. Two of R.E.M.’s most romantic songs are on this record: At My Most Beautiful ("I count your eyelashes secretly/With every one, whisper I love you"), and the hidden track I’m Not Over You at the end of the stunning Diminished. "I will give my best today", Stipe sings on Diminished, "I will give myself away", a vulnerability that only lasted for nine tracks on this fascinating record, before R.E.M. decided once again who they were. It’s nevertheless a mood that has fired my soul, and made my blood rush, for many years.

Jude Rogers

Lou Reed – Set The Twilight Reeling(1996)

(Sire)

After dealing with such weighty matters as urban deterioration (New York) and mortality (Songs For Drella, Magic & Loss), you’d be forgiven for thinking that Lou Reed would’ve been ready to kick back and take it easy with 1996’s Set The Twilight Reeling. Certainly, the opening of ‘Egg Cream’ wherein Uncle Lou extols the simple pleasure of the sweet, sugary drink of his youth would suggest so, but this deceptive greeting actually masks one of the weightiest matters of his life: where does a 54-year-old rock’n’roller fit into this crazy, mixed up world?

This is an album that searches for answers. Does he commit to a relationship (‘Trade In’)? Perhaps screw around for a bit (‘Hookywooky’)? Maybe steel himself for a life on his own (‘NYC Man’). It’s difficult to shake the feeling that he’s been badly affected by the death of Sterling Morrison (‘Finish Line’) but by the end of the album and its insightful title track, Reed has come to accept the inevitability of where life leads and to make the necessary preparations.

But this is also an album that rocks and unashamedly so. Reed and his band crank the amps up and clearly relish the utter joy that six strings and three chords can bring to anyone regardless of their age. Moreover, if any Lou Reed album is in need of re-appraisal, then Set The Twilight Reeling is it.

Julian Marszalek

Replacements mythology holds that it’s all about the albums they made for Twin/Tone. That Let It Be is one of the touchstones of US alternative rock (it is, but part of its charm is that half of it is actually, genuinely, truthfully terrible), that only when not giving a crap were they capable of achieving their full quota of brilliance. It’s orthodoxy, but maybe it’s wrong. The most fully formed Replacements album is the fifth, the first without firebrand guitarist Bob Stinson, Pleased To Meet Me.

The record gets remembered for tracks – ‘Alex Chilton’, the tribute to one of Paul Westerberg’s heroes; ‘Can’t Hardly Wait’, though even then plenty of hardcore fans express their preference for the demo of that song produced by Chilton, rather than the album version. But Pleased To Meet Me does something no other Replacements album does, or more accurately, it manages to do two things at once that their others could never manage simultaneously: rocking like lives were at stake, and holding together as a piece of work. And in the midst of the fearsome squalls of guitars – producer Jim Dickinson gave the Replacements the best sound they had ever had – came Westerberg’s most fragile, delicate moment, ‘Skyway‘. Let It Be is where the reputation was formed; Pleased To Meet Me is the great rock & roll record.

Michael Hann

Roxy Music – Flesh and Blood (1980)

(E.G.)

They began as hectic, electrifying pop-art collagists (Pleasure! Thrills!). Then Eno left, and they wound down with Bryan Ferry doing Jack Vettriano – a kind of singing butler. Right? No, the second bit couldn’t be wronger. You might reasonably think of early and late Roxy Music as almost two discrete bands. But the second is every bit the equal of the first, and Flesh And Blood is one of its two masterpieces.

While its gorgeous successor, Avalon, is perfect in its stillness – a calm silver pool eight miles deep – Flesh And Blood edges it on the songs. What songs they are; what extraordinary grace they possess. This is the most exquisitely inconsolable of post-break-up albums. ‘My Only Love’; ‘Over You’; the faintly Gothy closing ballad ‘Running Wild’; ‘Oh Yeah!’, with its masterful invocation of the power of music to pierce the heart; the sublime groove of ‘Same Old Scene’.

Without crossing over into those genres, Flesh And Blood is as spacious as dub reggae, as glittering and melancholy as late disco. It is a measure of the band’s justified confidence in Ferry’s writing that they should open by covering one classic – Wilson Pickett’s ‘In The Midnight Hour’ – and later feature another by The Byrds, knowing they will make these their own. Not only is Ferry one of the greatest reinventors of songs, but Roxy are sure the Flesh And Blood originals will match them. They’re right.

David Bennun

Royal Trux – Pound for Pound (2000)

(Domino)

Knocked out post tour in six days for just $5000, Pound for Pound displays Royal Trux at the height of their powers as the millennial boogie bar band experience par excellence. The band’s ever evolving funk-fried rock attack was in full effect on songs like slow-burning groove ‘Call Out the Lions’ and the rippling rock/soul clatter of ‘Deep Country Sorcerer’. Pound for Pound cemented Royal Trux’s reputation as a truly formidable rock entity without eliminating one iota of their avant garde edge. Chris Pyle and Ken Nasta’s twin drumming and Dan Brown’s slithering bass work are the perfect rhythm trio, providing a sleek and agile bedrock for Neil Hagerty’s taut riffing, languid soloing and Jennifer Herrema’s inimitable caffeine-drenched drawl. ‘Platinum Tips’ is a case in point, roaring by on little more than sizzling cymbals, classic backbeats and a tyre-squealing guitar lick. The album’s beauty and economy coalesces around ‘Sunshine and Grease’, a joyful call-and-response duet with Hagerty and Herrema in full-throated thrall to each-other. True partners in perfect sonic crime, the delirious noise of Royal Trux has been endlessly emulated, but will always remain unsurpassed.

Kevin McCaighy

Smashing Pumpkins – Zeitgeist (2007)

(Martha’s Music)

Billy Corgan’s resurrection of the Smashing Pumpkins moniker in 2007 was rightfully derided. Given the infamously obnoxious frontman’s decision not to warn his old bandmates that he was about start slapping their old group’s name on his future releases to drive sales, it’s unsurprising that the only other member accounted for on Zeitgeist is Jimmy Chamberlin (who only knew what was happening because he was drumming in all Corgan’s other projects at the time).

The thing is though, Smashing Pumpkins work well as a two piece. Who really cares if James Iha and D’arcy Wretzsky aren’t present? Corgan would probably have just overdubbed their parts anyway. Instead Zeitgeist‘s loose parameters allow him to crank the volume up to obscene levels and produce the heaviest album in the Pumpkins discography. The titanic ‘United States’ pushes the band’s overblown nature to the limit, while the album’s more delicate coda hints at what would come on Oceania. But the finest aspect of the record is the way Corgan builds everything around Chamberlin’s extravagant stick-work to create what might be the greatest air drumming album of all time. Just try to keep your hands still for the opening fill of ‘Doomsday Clock’. Impossible.

Josh Gray>

Sonic Youth – The Eternal(2009)

(Hostess)

There’s not really such thing as a bad Sonic Youth album. It’d be safe to assume their later work would not be replete with howlers you’d think me mad for sticking up for. Their final studio album, The Eternal, however, is not just another good Sonic Youth album, it’s one of their very best.

After the quick, blistering kick of opener ‘Sacred Trickster’ comes ‘Anti-Orgasm’, an upside down sprawling lurch of a track, an unholy, messy racket but somehow entirely focused; veering from louche riffing to a sudden primal, sexual thud. Elsewhere ‘What We Know’ is a focused, stomping classic.

Sonic Youth have always found brilliance in the clashes of chaos and beauty, there was never a point when they really lost that ability – but on The Eternal it felt like they’d found something further entirely. Had they not split up shortly afterwards, it could have been the start of a whole new era, but instead it must remain the worthiest of send-offs.

Patrick Clarke

Dusty Springfield – It Begins Again(1978)

When it was released in 1978, Dusty Springfield’s tenth studio album It Begins Again stiffed at Number 41 in the UK charts and disappeared. Producer Roy Thomas Baker said later that it didn’t warrant the huge $420, 000 budget (thanks Roy), and it has remained one of Dusty’s lesser-known records.

It is, however, an extraordinary example of 70s white soul – fluid, fragile, contemporary, poised, and stuffed with session players at the top of their game. Crusaders’ pianist Joe Sample, Steely Dan guitarist Jeff Baxter and drummer Ed Greene, for instance, while backing singers included Patti Brooks, Dianne Brooks and Brenda Russell. Dusty always hand-picked her singers, and here their swooping gospel notes are the perfect counterpoint to her husky contralto. It was definitely worth the money.

Stand out tracks include big ballad ‘I’d Rather Leave While I’m In Love’, the deeply vampy ‘Love Me By Name’ (her nod to the gay rights movement), and Barry Manilow’s kitchen sink anthem ‘Sandra’. Also delightful is the gentle satire of LA life, ‘Hollywood Movie Girls’, and disco throwdown ‘That’s The Kind Of Love I Got For You’. Dusty recorded this album after a painful period of obscurity, and sang with verve and emotion. Now is the perfect time for its resurrection.

Lucy O’Brien

Suede – Night Thoughts (2016)

(Warner)

Few bands have been written off quite so brutally as Suede were after everything fell apart into drugs and indifference after the release of A New Morning in 2002. Yet after their brilliant series of comeback shows and the excellent consolidation with Bloodsports, 2013 album Night Thoughts reached out even to Dog Man Star in its greatness. Accompanied by a powerfully moving film about the lost of a child by Roger Sargent, Night Thoughts had all the defiant street stomping belters of Suede’s glory years, but with a new finesse, deftness of touch, and an arguably more sensitive outlook. With Brett Anderson’s voice on peak form and talk of the band pushing their boundaries on the next one, their place in future incarnations of this list looks assured.

Luke Turner

Talking Heads – Naked (1988)

(Sire)

After two albums of plasticky eighties pop-rock, Talking Heads returned to the more groove-oriented sound they’d explored up to Speaking In Tongues. But this album is sombre, insidious. Even when they’re funkin’ out over Afro-Latin rhythms there’s a grotesque terror running through Naked that isn’t the same as the pale yelp of Fear of Music. The opener, ‘Blind’ is a horn-drenched noir caper through back alleys. David Byrne sounds more assured in his delivery than ever, but it’s matched by a paranoia totally alien to the preceding material on Little Creatures and True Stories.

Naked explores Byrne’s increasing interest in music outside of the US. The Highlife-influenced single ‘Nothing But Flowers’ shows a new side to his songwriting, with its running ecological gag. For the most part, Naked is a subtle, creeping beast. ‘Democratic Circus’ starts as a languid slither, later bearing its fangs with Byrne shouting ‘How we all laughed, we split our sides!’. It’s not their most popular album, indeed it seems to have alienated fans of both their early and mid-period work, but Naked acts as a satisfyingly dark closer to the Talking Heads’ catalogue.

Charlie Frame

Neil Young – Le Noise (2010)

(Reprise)

When guests peruse my vast collection of compact discs that line the walls, fill the shelves, rest in piles around the sofa and act as makeshift coasters, the first thing they ask is "Why do you remain so fiercely loyal to this near obsolete format, you Sonos-shunning neanderthal?" Their second question is always "And why must you insist on owning only the bad Neil Young albums?" As a connoisseur, I prefer to view them not as the bad ones but rather the most rewarding ones. Haven’t we all heard Harvest enough times already? Wouldn’t you rather expand your horizons with a concept album about electrical automobiles, live performances overdubbed with Rainforest Cafe-style animal sounds, scrawling feedback to rival Sonic Youth or a covers album recorded in Jack White’s refurbished Voice-o-Graph booth on which Neil talks to his dead mother? Best of all is 2010’s Le Noise. Here, Young drowns his songs in galloons of distortion and messes around with loop pedals to transform himself into a one-man Crazy Horse that’s apparently been fed on a diet of Earth 2, Aidan Baker, Tom Carter, Noveller, Jesu and King Tubby.

JR Moores