Do you catch yourself thinking about the end of the world? What prompts these thoughts? And are they all they seem? The idea pops into my head from time to time and I try and dismiss it quickly but it wasn’t until writing this feature that I realised how these unwelcome imaginings manifest themselves. I’ve now worked out that, shamefully, what I’m actually doing is playing a few frames worth of tsunami from the end of 2012 or running a mental GIF, culled from some other half-remembered CGI-blockbuster of skyscrapers falling down. On other occasions I’m conjuring up a stark image from the television of my childhood: the usual suspects are Threads or a Protect And Survive public information film (and the latter image is probably remembered via the secondary medium of the 1980s pop music video).

In reality (if you discount certain religious or cosmological predictions) the fall of man is too big a concept for us to envisage with any great clarity. When the end comes for our species it will probably happen in so many different and complex stages that it is all but impossible to second guess. (As much as the tabloids during the Cretaceous were probably constantly full of comet-based scaremongering, I bet none of them predicted a post-impact future where dinosaur survivors slowly morphed into birds who got smaller and smaller until the monkeys took over.) The (entertaining and lively) Homo Deus: A Brief History Of Tomorrow by Yuval Noah Harari is the latest product turned out by a publishing industry that caters to our still unquenchable millenarian thirst. Admittedly this book is unusual in that it actually has a relatively upbeat prognosis for us – homo sapiens is giving way to the god-like homo deus who will make war obsolete, conquer disease and achieve amortality – but like the rest of the literature dealing with the end of mankind as we know it, it’s no less far-fetched than most fantastical works of science fiction. Mapping out the future of man is like predicting the weather: experts can give us reasonable suggestions for the very near future but anything mid to long term is a fool’s errand due to the complexity of the model we’re talking about.

This publishing trend – a facet of a larger cultural obsession taking in TV series, magazines, films and comic books – services a large and amorphous client group of tens of millions who either believe that the world is about to end or fear that it could. These are the people who don’t push the thought out of their minds immediately but rather spend a lot of their waking time grappling with it. But if the end of our species is essentially unfathomable, what are they actually thinking about? In 2012, when talking about religious predictions of the end, the neuroscientist Shmuel Lissek suggested that large numbers of people found comfort and validation in the fearful “ancient bias” provoked by the idea of doomsday. This would be the ultimate example of misery loving company, or, as Robert Smith of The Cure summed it up succinctly in ‘100 Years’: “It doesn’t matter if we all die.” Counterintuitively there is also responsibility absolving relief to be had in ‘knowing’ when one’s time is due. It can seem bewildering to outsiders that many people under the sway of apocalyptic religions and cults are willing to believe the very precise warnings of the end of the world (down to exact dates and times) when literally all of these predictions so far have come to absolutely nothing. But perhaps it’s not hard to see the attraction in knowing exactly when you are going to die. For some people the sheer existential exhaustion they suffer comes from not having this knowledge. The complete failure of Earth to crash into the non-existent planet Nibiru on December 21 2012, will not stop people from getting in a flap over Sir Isaac Newton’s predictions of Armageddon when 2060 rolls around.

Eschatological and apocalyptic thinking is not just the sole provenance of followers of certain religious cults though. These ideas are often linked to those with poor mental health. I’m not talking so much about paranoid schizophrenics here. While it’s not unknown for the unhappy souls blighted by this condition to develop delusions – some of which may be apocalyptic in nature – in nearly all cases these beliefs are clearly irrational and in-all likelihood not persuasive to anyone other than the sufferer themselves. More relevant here are the paranoid, who have relatively more rationalised fears, which are often easily expressed and shared, especially via the internet. (It is a common belief among hardcore conspiracy theorists for example that their government has information about an immanent disaster and are purposefully keeping the population in the dark so as not to cause panic.) And then there are the traumatised. There is evidence that people suffering from post traumatic stress disorder – especially those who have first hand experience of war itself – can buy into the mindset of apocalyptic survivalism becoming “preppers”. These characters are now so prevalent in American society that they have become a stock archetype of pop culture, with prominent examples such as John Goodman’s survivalist character Howard in the smart sci-fi movie 10 Cloverfield Lane and the Indiana doomsday cult leader the Reverend Richard Wayne Gary Wayne from the Netflix comedy Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt. In the States, bookstore shelves are heaving with titles on the subject of ultimate survivalism and there are even several popular magazines designed to help people with their preparations.

And all of this is before we get onto the beliefs of some folk who are simply very very depressed or fatalistic.

In some of these cases the standard pop-psychiatric explanation of apocalyptic thinking would be something along these lines: the damaged mind is unable to process its own collapse and projects its own chaos outwards onto the world. But – to paraphrase Tom Waits – just because you’re crazy and thinking about the apocalypse doesn’t mean the end isn’t actually nigh…

It was reported in the news recently that the notional big hand on the Doomsday Clock, a symbol which represents the likelihood of a human-caused global catastrophe, has been moved to two and a half minutes to midnight. It had previously been at three minutes to midnight for two years which was the closest it had been to 12 since the height of the American/Russian nuclear standoff in 1982. If you’re having trouble interpreting what this recent change means, the Science And Security Board of The Doomsday Clock had this to say last year: “The probability of global catastrophe is very high, and the actions needed to reduce the risks of disaster must be taken very soon.” They have amended this statement thus: “In 2017, we find the danger to be even greater, the need for action more urgent. It is two and half minutes to midnight, the clock is ticking, global danger looms.”

As their name suggests, the Science And Security Board are not so much concerned with religious predictions as they are manmade disaster. But some these scientific scenarios are no less baroque when you read about them…

Phil Torres, author of The End: What Science And Religion Tell Us About The Apocalypse, lists a dizzying number of ways in which we may shuffle off the coil en masse. There is the threat of super-intelligence, grey goo nanotechnology run amok and the appalling idea of ‘catastrophic vacuum decay’ (if you’re excessively existentially nervous and don’t already know what CVD is, I really wouldn’t google it). And then we have the only slightly less bleak but all too tangible climate change and nuclear war scenarios – which rather than threatening to wipe everyone out in one fell swoop would light a long and complex touch paper on the process.

So, given this looming danger, I’ve found myself wondering recently, why isn’t more music being released in 2017 about the apocalypse or the idea of post apocalypse?

Now, this being the internet I have to explain very carefully what I mean here. First of all, I don’t mean that no music at all currently deals with the idea that the world is ending. There have been quite a few examples of musicians indulging in apocalyptic thinking recently. Ed Harcourt’s album Furnaces may use the concept as a metaphor to explore the transcendent salvation offered by love but his vision is still mired in fire and brimstone. His manager, the critic Sean Adams, says that despite offering the listener the possibility of salvation Harcourt still imagines a world of terminal pollution and dissolution. And last November ANOHNI released ‘4 Degrees’ as the lead single from her latest album Hopelessness a stark and lacerating ecological warning. But for the most part these sentiments are conspicuous by their absence in the mainstream – especially when TV channels, cinemas, computer game stores and bookshops are so replete with apocalyptic and post apocalyptic fiction and entertainment.

We also need to recognise the few hardy souls who have been proclaiming the end of the world for decades now. As such we should pause here momentarily and doff our caps towards Jaz Coleman of Killing Joke. This year marks the 35th anniversary of his departure from these shores for Iceland convinced of the coming apocalypse. Much mocked in the music press at the time, Coleman now lives in a jerry built house on an island in the relatively remote Hauraki Gulf of northern New Zealand (mythologised as Cythera by Coleman). His attitude of wishing to live as remotely from major cities as possible seems a bit more sensible in 2017 than it used to, not the least now that the idea of relocating the family to Canada, Patagonia or, yes, Reykjavik has supplanted house prices as the number one subject at dinner parties all over the UK. But it should be said that by their own standards at least, Coleman’s lyrics seem slightly less apocalyptic than they used to be and recently, in a Q and A after a screening of The Death And Resurrection Show Killing Joke documentary, when the subject of his initial stay in Iceland was mentioned, he brought up a life-long struggle with depression suggesting that there is perhaps a mental health aspect to at least some of the band’s end time concerns.

For the sake of brevity we’re going to have to give heavy metal a free pass here. The subject of the genre’s obsession with the fall of man is enough to generate several volumes of scholarly work and cannot be generalised upon to any useful degree. There has been more amazing metal concerned with the end of days than from all other genres combined. From Black Sabbath’s ‘Electric Funeral’, recorded in 1970, onwards, it has seen many towering peaks of achievement such as the foundational Viking metal album and poetic 1991 masterpiece Twilight Of The Gods by Bathory (named by Stephen O’Malley as one of his favourite meditations on the subject).

However, it is worth pointing out to the non-partisan and metalphobic that apocalypse doesn’t always mean apocalypse when it comes to metal. Even after skipping over the heavily metaphorical nature of this music, things are not always as they seem. For example, the mushroom clouds on the cover of a neo-thrash LP by Reign Of Fury or Havok might seem in poor taste to someone with little interest in this genre, but to a metalhead of my age (mid-40s) this is primarily a nostalgic, comforting image, more redolent of a carefree adolescence lit golden coloured by rite of passage first beers and enjoyment of records by Megadeth, Nuclear Assault, Iron Maiden and The Cro-Mags, than it is symbol of imminent global destruction.

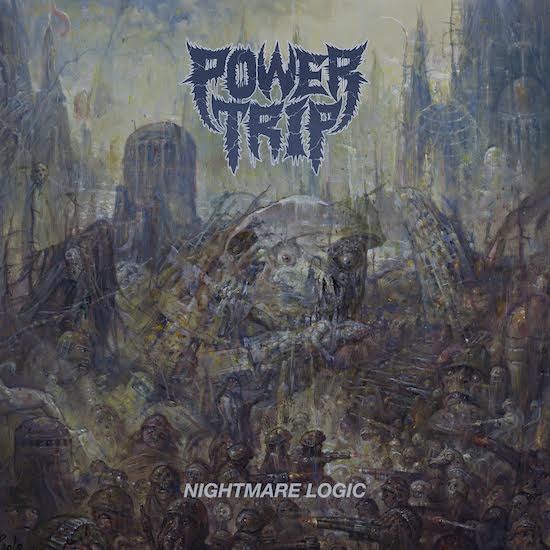

And it’s also worth bearing in mind that there can often be a disconnect between lyrical content in extreme metal and the art the album comes in. Take Texan thrashers Power Trip for example. The sleeve of this year’s Nightmare Logic on Southern Lord is all demonic soldiers marching through a post nuclear cityscape with a deathly face surveying the carnage but the lyrics of singer Riley Gale – who has a sophisticated line in identity politics – are mainly about the effects of globalisation and neo-liberalism and what can be done to resist, inspired in part by UK second wave punk. Nothing is necessarily what it seems when it comes to metal.

One recent metal act that has really stood out to me because its entire aesthetic over several releases seemed to be exclusively and persistently about the end of the world was the Botanist. Even by black metal standards, the Californian who goes by the name of Otrebor and plays drums and hammered dulcimer while singing, is a complete outlier. He has released six albums proper as the Botanist – a character who represents the nemesis of mankind, his work: allowing plants to regain control of the planet after humanity has died. The intense lyrical devotion to this messianic eco-terrorist character, married to the transcendent blur of music, wrenched from non-standard instrumentation, marks this music out as totally unique.

Most other modern genres pale in comparison to metal in the apocalypse stakes. Some producers of noise, techno and dark ambient talk a good Omega game but the lack of lyrical content makes this little more than a colouring agent in my book. Elsewhere, I can detect a subtle millenarian undercurrent to hauntology – probably because of the shaded section on the Venn Diagram that crosses over into Protect And Survive booklets, public information films, Threads and so on. I asked Simon Reynolds if he believed these hauntological fetishes were totally removed from modern day worries about nuclear war: “I don’t think it’s to do with apocalypse or nostalgia for nuclear war or anything daft like that, it’s an aesthetic thing – [people] love of the look and sound of those Public Information Films as little capsules from another time. There’s also a sense of wonder that such creepy, unnerving things were shown to children.”

And even then, when we put our heads together my initial assumption that there would be untold numbers of hauntological recordings about impending doom seem to be somewhat fanciful. There is the ‘Civil Defence Is Common Sense’ track on The Advisory Circle’s Other Channels album and the nuclear war inspired Tomorrow’s Harvest by Boards Of Canada (again, as much as an instrumental album can be said to be about anything).

A recent album he was keen to mention was A Year In The Country’s The Quietened Bunker, before adding: “But again that is more about the bygone long-ago vibes of Britain at a certain time in post-War history than anything to do with current concerns.”

So actual sonic hauntological artefacts dealing tangibly with apocalypse as we might fear it today are quite the rarity. A notable example would be the Radiophonic play, Eschatology, which the Langham Research Centre and Peter Blegvad performed on BBC Radio 3 in 2014. The full play is fantastic – like the shipping forecast broadcast from a vessel scuttled at the lip of oblivion, and mixes spoken word drama, musique concrete, vintage synth-scaping and tape experimentation.

When listening to this play again recently, the idea of a story told from the POV of the last people on Earth after an apocalyptic event, set to non-standard musical backing put me in mind of one of the jewels in the crown of American rock group Shellac – ‘The End Of Radio’. Over a tense solo snare beat that inexorably creeps up to double time and then beyond into a puncturing drum roll over a rigid, metronomic bassline, Steve Albini barks out the story of the final broadcast of a Modern Lovers-obsessed radio DJ who finds himself the last man on Earth broadcasting his final show to… no-one. “Is it really broadcasting if there’s no one there to receive?” asks Albini plaintively before eventually unleashing the riff of all riffs, which sounds like Link Wray on the deck of Event Horizon. As different as they are, the power of both pieces can be found in specific effects achieved by the combination of (non-standard) music and spoken word, but more on this later.

Now, anyone reading this article would be well within their rights to ask, why should people even want be reminded of the parlous state of international affairs or impending ecological destruction when they’re listening to music? Why shouldn’t they be allowed to enjoy pure escapism – an attitude I have a lot of time for. But one only has to look back 35 years to when the Doomsday Clock was as perilously close to its terminal engagement as it is now to see how much things have changed. In the 1980s – when Russia and America seemed likely to engage in nuclear warfare, it wasn’t just the thrash metallers, goths and punks who were obsessed with doomsday – it was everyone from Frankie Goes To Hollywood to Heaven 17 to Ultravox to Morrissey to David Bowie to Blondie to Queen to Nik Kershaw to Sting to Prince to Genesis to Nena to OMD… Name a top ten single from 1983 – there’s a fighting chance the theme was nuclear annihilation.

So something has changed but what?

Recently, after the untimely passing of the theorist and music critic Mark Fisher, I had reason to go back and re-read his essential text Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? In his opening gambit he claims the idea that it is easier to picture the end of the world than it is the end of capitalism (attributed to both the erratic Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Zizek and the postmodernist Frederic Jameson) as the essential motto for Capitalist Realism.

There is a difference between 1982 and 2017 according to Fisher’s book and that is now there is simply no alternative economic system we can imagine to the one we’re saddled with. In the 1970s and 1980s – no matter how naive, how unrealistic, how compromised, alternatives in name still existed to capitalism. Socialism existed as a genuine force, anarcho collectivism existed as a genuine possibility etc. Now that the after effects of Thatcher’s second and third terms have settled in comfortably – so the argument goes – we simply cannot imagine anything other than the system we have now. Fisher described the state of inertia we find ourselves in: “What we are dealing with now… is a deeper far more pervasive sense of exhaustion of cultural and political sterility… For most people under twenty in Europe and North America, the lack of alternatives to capitalism is no longer even an issue. Capitalism seamlessly occupies the horizons of the thinkable.”

World destruction, of one kind or another, is the inevitable end product of capitalism. It is now a near global system predicated on continual and aggressive expansion of markets by any means necessary in a world of finite resources that has only a limited capacity to cope with our core rapaciousness. There is no other way things can pan out. So it struck me as being quite funny that it’s now equally as hard (for musicians at least) to imagine the end of the world as it is for the rest of us to imagine the end of the system that’s causing it.

I’m not sure what I think about the paucity of ‘this kind of music’ in the mainstream these days. After all, even if it was widespread and popular, surely it would just be an example of pre-corporation (“the pre-emptive formatting and shaping of desires, aspirations and hopes by capitalist culture”). Just another temporary trend. And by the way, this isn’t some semi-occluded old man cry about a so-called lack of protest music in the 21st Century. There is enough of that stuff about – I’m aware that it doesn’t look like it used to and most of it is now guided by liberal humanism rather than a naive desire to save the world from nuclear or ecological destruction.

But popular or not, the more music struggles to get away from the cultural exhaustion of late capitalism – the more it resists mere revivalism and straight up pastiche – the more effective I find it on several levels. I don’t need music to be sui generis, I just need it to fight its own fucking corner, god damn it. And so it is with apocalyptic music. As with all of the examples mentioned above, I’ve found myself returning to the self-titled debut album by Manchester based artist Vanishing time and time again recently.

Vanishing is a project led by Hull-born and Manchester-based poet and musician Gareth Smith (who is, among other things, a regular collaborator with LoneLady). His music isn’t as overtly obsessed with the coming collapse of civilisation as that of the Botanist, say, but it has been riven by millennial angst. (Smith has only talked in very general terms about how Vanishing is concerned with "alienation and claustrophobia"; about "this terrible feeling of dread"; and "the madness of the current time" but it seems to me that it could present a means for him to articulate extreme sensitivity to modern life, as this music jangles like a symptom of generalised anxiety disorder.)

On this debut album, released recently on Salford’s Tombed Visions, he has created a cast of characters such as The Forger and The Cleaners, and to breathe life into them he does the police in different voices. His words come flowing dynamically out of him in an East Yorkshire accent as heavy and blunt as a cosh; a necrotic black metal shriek; a granular baritone drawl; a tremulous whisper that rises and rises towards an ever ascending note of anxiety ringing clear like a struck bell. And his words exit him like ten thousand cubic metres of silt, suspended in the garbage rich, caramel brown waters of the Humber flowing right out into the desalinated and mercury poisoned North Sea.

It’s not a particularly easy listen. But it is thrilling.

Vanishing by Vanishing, is on first listen heavily portentous, achingly pompous, grindingly dour and massively out of step with the current cultural times. Of the few who hear it, no doubt more will be annoyed than pleased by it; certainly more will find it wryly amusing rather than harrowing. It does however despite all this reveal itself on subsequent listens to be quite brilliant.

Vanishing is not an exploration of something that has already happened or something that is going to happen but something we are currently enduring. It is a sonic metaphor for how we are refusing to feel right now. The stab of panic late at night when anxiety stalks the hallway outside the door, when no amount of digital distraction will quell the thought, "What have we done?" Smith isn’t saying what we’re all thinking, he’s saying what we’re all desperately trying not to think.

Musically, this is a muscular and psychedelic mix of post rock, industrial, dark ambient, dub and other, less-easy to classify, fractured and cosmic sounds, provided mainly by Smith with Paddy Shine of GNOD. (Shine’s bandmate Alex Macarte also turns up on synths at one point while Julie Campbell and Elizabeth Preston add a hint of Godspeed drama on cello here and there.) The churchical organ drones of ‘Brighton 84’, the brittle Suicide-beats of ‘Night Vision’, the nerve-jangling dub effects of ‘Fountain’, the future spiritual of ‘The Forger’ and the reverberant, agonising power electronics of ‘The Cleaners’ all thrill… ‘Bronze Misnomer’ is a quirky but threatening reboot of Jack Kerouac, Al Cohn and Zoot Sims’ Blues And Haikus from 1959. Behind all things is glitchy electronica like the sound of the machines stuttering and failing for the last time. Over all things is a scree of noise as long since abandoned buildings eventually crumble, undermined by encroaching plant life. If I have one major criticism of Vanishing it is that, like TS Eliot’s ‘Strawmen’, it whimpers out of existence instead of ending with a bang. On final track ‘Glacier’, the guitars – bum notes and all – meander aimlessly about the track and for once the music is not really a match for Smith’s simmering intensity. But perhaps this is an apt way to end proceedings.

Vanishing isn’t going to change the way I vote. It’s not going to affect the way I do my recycling. It’s not going to make me join the Green Party. Listening to this album is not going to make me go and live in an island shack near the Hauraki Gulf. It isn’t even going to make cross the room so I can turn the light off that’s currently switched on needlessly in the hallway. But this album (along with the music mentioned by Langham Research Centre, the Botanist, Shellac and The Advisory Circle among many others) serves as a concrete reminder that there is respite to the cultural malaise created by late capitalism for those who are determined to seek it. It makes me think there is a glossary of effects begging to be written detailing how various literary techniques combine with certain musical processes to create dramatic new sonic spaces. And I’m not just talking about apocalypse music now, but songs about love, death and birth as well. Songs about cars. Songs about nightclubs. Songs about buildings. Songs about food. One really only needs to feel the surging connective potential when listening to something that doesn’t sound quite like anything one has heard before, related from an angle one hasn’t considered before – as infrequently as this may occur – to realise there is still everything left to fight for. Those who claim they’ve heard it all before? I lament their inability to see anything but the broadest of brushstrokes when the rest of us know the devil is in the detail. They say: "We’re doomed! We’re doomed!" I say: "Not a bit of it, there’s enough hope left yet."