What’s black and white and read all over?

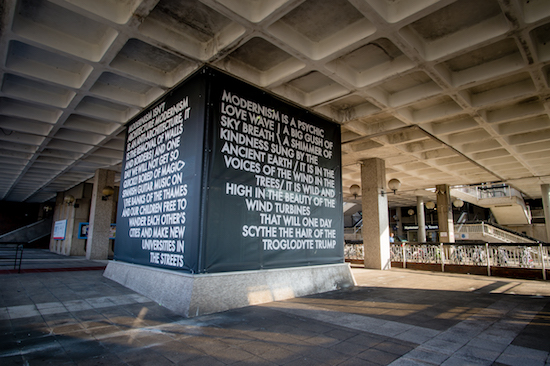

The answer is artist, poet, and agitator Robert Montgomery’s monumental new installation called Hammersmith Poem. Unveiled this week at Hammersmith Town Hall, the stark fabric of the six-metre-tall poem wraps a glass atrium under the brutalist extension of the building and adds a new dimension – literally – to Montgomery’s work to date.

Now aged 45, Montgomery primarily studied painting at Edinburgh College of Art. But as a fan of poets and lyricists ("There’s no one better than Bob Dylan!"), he’s forged a career using the written word. In his early days, he hijacked outdoor advertising spaces by plastering over them with his rants, musings and prose.

Speaking to Montgomery on the windy day of the poem’s unveiling in Hammersmith, he says with a smile: “Let’s say I was acting in an ‘independent’ way – I wasn’t asking for permission. I was just covering up the ads. I don’t think we need to be told 100 times a day that Diet Coke is fizzy and that it tastes great.

“I began working in the streets. And I’m really interested in hijacking at that scale and bringing a different kind of speech to public spaces. In the beginning, I was just going out in Shoreditch [where he lived at the time] and put posters over adverts. I think it’s generally therapeutic to find a poem in place of an advert on the street.”

His guerrilla poetry led to an incredible array of (now sanctioned) text-based projects and platforms since 2005, including fire poems at The Louvre in Paris and the Edinburgh Art Festival, to LED and illuminated signs, billboards, watercolours, and even repurposed aviation light boards at Berlin’s mothballed Tempelhof airport.

Channelling the Situationist revolutionary ethos of Guy Debord, the tousle-haired dead ringer for Johnny Depp is most obviously influenced by the work of Jenny Holzer.

However, Montgomery succeeds in moving her word art concept along by appropriating a newfound surrealism and nihilism, alongside her profound challenge to authority. These elements remain the hot streak running throughout his work. His style and results are perhaps best described by German writer Manuel Wischnewski: “A moment of ghostliness is often pointed at: words that appear so unexpectedly in the streets of our cities and disappear again, as if spoken from nowhere. Words that are not bound to an actual speaker, but rather to a place or moment.”

Yes, it’s really "easy" to protest about stuff, Montgomery admits. “And sometimes I do that. But I also try really hard to find an element of hope and find a positivity in the chaos of life. I want to cause positive disruption – in a punk rock way.

“But it’s different in Hammersmith. The poem embraces a place and a moment in time that is epitomised by the architecture. The work is very specific to the special building. I had already been doing a bit of work with placing some of my texts on modernism upon black squares.

“The black squares were the preferred symbols of [Russian artist Kazimir] Malevich, who used them to make arguably the first abstract paintings at the turn of the century. Because to me, modernism is a set of values, not a style. The architecture of Hammersmith Town Hall is so perfectly modernist that it became the natural place to blow up my idea on a larger scale.”

What Hammersmith & Fulham Council and the nearby Lyric Theatre were expecting when they commissioned Montgomery to kick-off their new series of public art installations is unknown. But they got Montgomery at his best – big, bold, and impassioned.

Designed to be read from any angle the poem is full of surreal turns of phrase as well as more direct political challenge. Or in its concluding lines, an impressive amalgam of both: “It is wild and high in the beauty of the wind turbines / That will one day scythe the hair of the troglodyte Trump.”

At first glance it’s the Scottish-born London artist referencing Trump’s continued objection to the offshore windfarm planned near the president’s Aberdeenshire golf course – a case which he lost in the courts last year. But it’s a trope for Montgomery to firmly ground his poem in a general celebration of the civic values of Britain.

Or more specifically "the progressive values focused on free education, health care, and racial and social equality", Montgomery says. “Public libraries and wind turbines are the most beautiful achievements of modernism. We must not lose sight of those ideals and that dream of freedom.

“And we definitely need to speak up for these values in the face of current demagogues. Trump is a terrible anti-modernist. He is not the beginning of a new movement. Rather he’s the last-gasp of a backward-thinking ideology which has failed and is killing the planet.”

The installation is a startling addition to the weighty concrete extension that rests above it. Completed in 1975 it is one of the most-striking examples of brutalist architecture in London. Its perilous suspended walkways connect it to the main Grade II-listed Swedish art deco red brick town hall of 1939, which fronts the river and the A4 to the west of the Hammersmith Flyover.

It’s hard to find a more dramatic contrast between the majesty of the Thames and the bleak urbanity of central Hammersmith. Yet Montgomery’s poem is a fitting mash-up of these realities – with the area’s hard edges reflected in his signature bastardised Futura font, while its more prosaic elements are echoed by the poem’s hopeful imagery.

Where else but outside a Labour-run council in West London could he get away with opening lines such as: “Modernism isn’t / Architecture modernism is a dream of free education and racial/ Equality and/ Libraries full of books and dreams no longer full of tears/ The air chases + scatters blue/ Light more than it/ Scatters red light>> That’s why the sky is blue when we are cloudless, when it is big-gushed.”

Montgomery declares: “It has humour. It has metaphors. But I hope it works as a bit of a wake-up call, in terms of recognising the importance of our publicly-funded institutions and publicly-funded culture in this country. It’s something that we need to celebrate. And retain.”

Robert Montgomery’s Hammersmith Poem is on display at Hammersmith Town Hall, West London, until 1 July