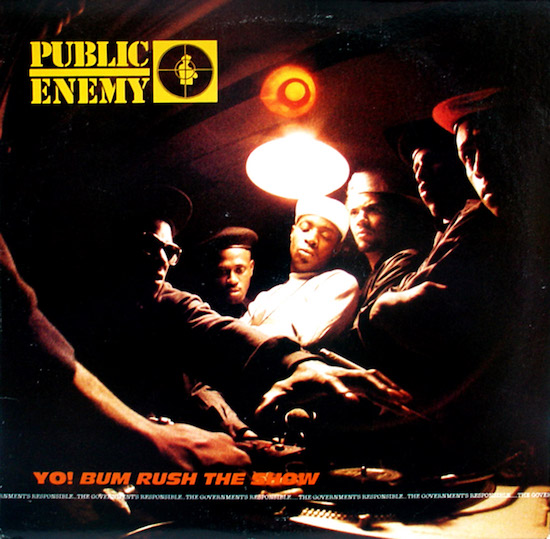

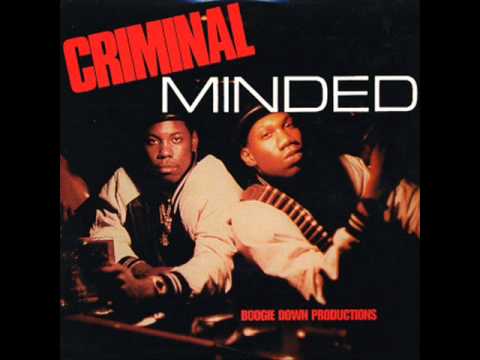

There’s a power to the number three that seems to defy rational explanation. Maybe it’s as simple as the fact that two instances of something could be the result of coincidence while three is a pattern; maybe it’s that it’s the smallest number of legs you can put on a stool or a table without it falling down; or it could just be that when things come in threes it feels more naturally resolved than twos or fours. Whatever the reason, we appear hard-wired to respond to things when they arrive in threes, so in 1987, when three hip hop groups released debut albums (and one follow-up b-side) that redefined the possibilities of this still-controversial music, listeners the world over began to take note. Criminal Minded, Paid In Full, Yo! Bum Rush the Show. Boogie Down Productions, Eric B & Rakim, and Public Enemy. The trio of albums that ushered in rap’s golden age, and launched the careers of hip-hop’s holy trinity. It was quite a year.

That the three groups – and their key individuals, in lead rappers KRS-ONE, Rakim and Chuck D – saw themselves at the vanguard of a new movement may not have been a given at the time, but was certainly acknowledged later. KRS wrote a song on BDP’s third album, Ghetto Music: The Blueprint of Hip-Hop, released in 1989, called ‘Bo! Bo! Bo!’ in which the character he is portraying in the song (someone similar to KRS in every respect but taking part in a fictional narrative) is rescued from a tricky situation when a car squeals to a halt, the door is thrown open, and he’s helped inside then driven away by Chuck and Rakim.

All three were outsiders: Chuck and Rakim from Long Island, miles from hip hop’s New York epicentre, and while Kris had been in the Bronx and had seen hip hop’s birth at block parties and park jams, at the time of his debut’s creation he was homeless. Chuck was the oldest, Rakim – only 16 when he began working on his album – the youngest. Public Enemy’s record was released by a major label, and was the least successful at the time, both commercially and critically; Rakim’s was made by an independent imprint but bankrolled by a subsidiary (of, in turn, another subsidiary) of a quasi-major. KRS’s album was released by a label so new, small and unaffiliated with any other company of substance, with business practices so homespun and ad hoc, that its maker claims, to this day, to have never been paid a cent from the original release nor its many and varied reissues. But there was a mutual interdependence between the three, a collective sense of this music both representing and fuelling a changing of the guard, and – most importantly for the new culture they were all helping to shape – each heard developments in the others’ sounds and styles that caused them to reassess their own music and to rethink their art anew.

Although released within a few weeks of each other, each record is stylistically different, and was made in a distinctive way. Criminal Minded may have appeared to be the work of a duo – KRS and DJ Scott La Rock – but benefitted hugely from the production input of Ultramagnetic MCs member Ced Gee, whose approach to sampling involved using the SP-12 drum machine to play newly programmed beats made up of individual drum sounds taken from old records. Public Enemy had Flavor Flav as a lyrical and vocal counterpoint to Chuck, and Rakim’s voice shared part of the billing on Paid In Full with Eric’s DJ-ing (there are two bona fide DJ tracks, and one instrumental, among the album’s 10 songs). Scott may have been the subject of one of Criminal Minded‘s ten tracks – the ribald ‘Super Hoe’ somehow managing to project an air of menace and violence despite being designed to celebrate La Rock’s popularity with women while pushing a safe-sex message that would be expanded on in later BDP albums – but Criminal Minded is more definably KRS’s album than Bum Rush is Chuck’s or Paid In Full is Rakim’s. Track after track, he projects a complicated combination of self-taught intellectual, contemporary urban historian and didactic rap innovator. Throughout, he is always trying something new – vocally, lyrically, or both. Set inside Ced’s and Scott’s conception of a new form of rap – where organic samples were taken from everybody from James Brown to AC/DC then viciously chopped before being reconfigured into new shapes – KRS was pioneering a new rap language.

This combination of the human and the mechanistic gave the record a slightly cyborg feel, one that Yo! Bum Rush The Show also conveyed but for different reasons. The Bomb Squad had not yet been inaugurated, and producers Bill Stephney, Hank Shocklee and Chuck (appearing under the name Carl Ryder, a bowdlerised abbreviation of what appears on his birth certificate) chose samples with a thin, sometimes mechanical sound, and pushed recording technology beyond its then-current limits to make the record. ‘Public Enemy Number One’ featured a sample from The JB’s ‘Blow Your Head’ that ran far longer than then-current sampling technology could handle: the problem was resolved by engineer Steve Ett, who made a loop of analogue tape and ran it round microphone stands set up across the studio, because the actual physical loop was too long to be played on the reels of the tape machine. Their sound was denser, an antithesis of the different kinds of comparative minimalism that Criminal Minded and Paid In Full adopted. Scott, Ced and KRS may have sampled ‘Back In Black’ to make ‘Dope Beats’, but it was PE who were closest of the three to rock. Among Chuck’s earliest plans for Public Enemy was for the band to be rap’s version of The Clash, and there are echoes of this – particularly the confrontational, aggressive sound, despite the low tempo, of the abattoir howl ‘M.P.E.’, and the clenched-fist politics of ‘Rightstarter (Message to a Black Man)’ – throughout the record.

Eric and Ra included both sides of their debut single – ‘Eric B Is President’ and ‘My Melody’ – which they’d recorded with sample innovator Marley Marl in his flat in Queensbridge, and added self-produced tracks that relied on looped samples of records Rakim had cut his teeth rhyming over in park jams and battles out in his home town of Wyandanch. The sound is sparse, largely empty, which gave the duo three key advantages. First, there was no need for Rakim to bark, never mind shout, to be heard above the fray: his honeyed baritone was instantly revealed as one of the most distinctive instruments in rap history, and his delivery allowed for a more musical approach to rap than had been attempted before.

Second, when Eric scratches (and while there’s some debate about which parts of this he does on ‘Eric B Is President’ and ‘My Melody’ – Marley Marl claims he did a lot of the scratches, saying Eric contributed only the "sloppy" ones – there’s no doubt it’s him on the best DJ performances on the album: ‘Chinese Arithmetic’, ‘Eric B Is on the Cut’ and ‘I Know You Got Soul’) the sound is full, clear, and almost physical – if scratching is percussion, this is a beautifully miked snare rather than a sibilant hi-hat: instead of reminding you you’re listening to the sound made by a tiny crystal sat in a groove a fraction of a millimetre across, this feels more like what you’d hear when a gigantic mechanical mining tool attacks the walls of a canyon. When PE came to record ‘Rebel Without a Pause’, the track was so stuffed with different elements across all available sonic ranges that Terminator X’s scratches wouldn’t cut through in the mix until the low range parts of the records he was using were tuned out. Few records in hip-hop history have made scratching sound as vital and exciting as the technique does on Paid In Full.

Third, the space allows the duo to be subtle with the music in a way that enhances a sense of mystique, encouraging repeated listens. Elements such as the individual, almost accidental inclusion of a guitar lick from James Brown’s ‘Funky President’ in ‘As The Rhyme Goes On’ gives the production a depth and a nuance that intrigues and beguiles. Throughout, the album is a beautiful paradox – its spacey and light overall texture enabling extreme heaviness and punch from bass and scratches.

The relative simplicity – or sonic austerity – may also have helped in a crucial, practical way: by speeding up the recording process. With three of the album’s ten tracks instrumentals, and both sides of the debut single included, only five new finished songs were needed to complete the LP. It was the last of these three albums to be completed, so by definition had the most up-to-date sound – vital at a time where the genre was being moved forward at incredible speed.

"Back then you couldn’t have records that were stale," Chuck told me in an interview conducted in 2003. "You had to be now, and be cutting edge – go to the next zone." This was a problem for the band, who were signed to Def Jam, the label run by their manager Russell Simmons and associate producer Rick Rubin: Def Jam had struck a distribution deal with the major label CBS, so had lost the first-mover advantage of the true independent. Their releases now had to fit in to the major’s schedule. By the middle of 1986 this was becoming a big problem for PE, who had been sitting on the album for a while, and on its first single – ‘Public Enemy Number One’ – for longer.

"’Public Enemy Number One’ was coming out summer of ’86," Chuck said. "But Springsteen came out, [the Live/1975-85 box set] which pushed out the Beastie Boys, which pushed us back. So instead of coming out in October we had to come out in February, March, maybe, if LL didn’t get his album finished and pushed into the CBS system! We had ‘Public Enemy Number One’, which was a street record in Long Island and Queens since ’84, ’85, so it was out-dated – the lyrics were out-dated, the voice style was out-dated. We knew that if it had of come out during the summer of ’86 we could’ve got that [cutting-edge vibe], because we had a little bit of an element of that sound in it, that sound that Boogie Down Productions and, really, Eric B & Rakim introduced, with ‘Eric B Is President’."

The making of which is another story in its own right. Here’s Rakim, taking up the tale during a 1996 interview.

"I met Eric B in ’85," he told me. "I knew this brother named Alvin Toney, I used to live near him out in Long Island. We used to play in the football team together. Alvin lived right up the block, he knew Eric B, and Eric was out in Long Island lookin’ for an MC, because Eric was about to set his career off. So Alvin Toney brought him to my house, and I had a little tape I put together. I put the tape in, and Eric was diggin’ the tape. He took it to Marley Marl and [New York hip hop radio DJ] Mr. Magic, let them hear it, an’ they was diggin’ it. So we went to Marley’s house and used his studio and did a two-cut demo, which was ‘Eric B Is President’ and ‘My Melody’. Then we took that to [independent label] Zakia, which was the first place Eric took it to. Zakia gave us a little album deal. To be truthful, I didn’t know it was gonna blow like it did.

"I used to think that the computer sound was like a plastic sound, and the real bands, you couldn’t get no realer," he continued. "I always liked the real music, the real instruments. And I felt comfortable rhymin’ over breaks. As far as the rhymes, at that time the style of rap was different. Brothers was screamin’ at the top o’ they lungs. The brothers that was gettin’ paid off it was like Run – he was always from the top of his lungs. But the way I wrote my rhymes was to fit me. I’ve always been a laid-back person, so my style was a little more laid back. We just came with what we felt."

The collaboration with Marley Marl was fortuitous. Already by that stage, the Queensbridge producer had made a significant name for himself in the nascent hip hop world, producing hits for some of the biggest emcees of the day, including MC Shan and Roxanne Shante. As well as his links to Mr Magic, enabling him to get his new tracks onto New York radio within hours of completing the mix, Marley had a studio set up in his apartment, so could record morning, noon and night at no cost. His methods were, to say the least, unconventional – but when it came to ‘Eric B Is President’, no-one could fault him for a failure to stick to the concept.

"I used the kick and snare from [The Honeydrippers’] ‘Impeach The President’, but I tapped it out as [James Brown’s] ‘Funky President’," Marley told me in 2007. "I used the same pattern the drummer had used, and tapped it out [on a sampling drum machine] the same way – but it was the ‘Impeach The President’ kick and snare." The bass line was copped from Fonda Rae’s ‘Over Like A Fat Rat’, but wasn’t a sample: Marley replayed it on a keyboard. For ‘My Melody’, things were similarly basic.

"That was actually [Keni Burke’s 1982 soul track] ‘Risin’ To The Top’, replayed off a Casio CZ101 keyboard," Marley laughed. "A little bullshit keyboard! And the funny thing about that record? When the sound changes, when it goes from the whistle to the ‘boom, boom-boom’…? I was really changin’ the program right there live! I didn’t have [enough] tracks, so I was changin’ it live while recording. So cheesy! This was all four-track [recording] – snare and hi-hat on one track, kick and bass on the second – I always put the same frequencies so they don’t clash – vocals on another one, then cuts [scratching]. And that was our song."

The remainder of the album came together quickly, the five vocal tracks built in a similar way, though the duo worked without Marley’s help. Rakim brought records to sample from tracks he’d rhymed over in Long Island park jams or temporarily purloined from his parents’ collection, while Eric supplied the cuts and scratches. Steve Griffin, Rakim’s brother, replayed various bass lines that appear on the album as interpolations rather than actual samples. The process is laid bare for everyone to hear in the ad libs that bookend the title track, its single verse emphasising the get-in, get-out, get-it-done-and-get-paid mentality the song (and the album sleeve) investigated and celebrated. The duo were already enjoying the fruits of their labours, a cheque for $17,000 each received as an advance from Zakia – who had in the mean time cut a deal with the Island-owned 4th & Broadway label, who would release the album. The album title and concept came from the words rubber-stamped on those very cheques.

"I remember we were in the studio when Eric brought the two cheques," Rakim said during another interview, this one in 2007. "Before that we was gettin’ cash all the time – we’d heard about Zakia Records! This was the first cheque we got. When he handed me mine, I was just lookin’ at it, and Eric was like, ‘That’s it, Ra!’ I said, ‘What?’ And he said, ‘That’s the name of the album.’ I said, ‘What? Bank of America?’ [laughs] He said, ‘Nah – Paid in Full‘!"

Had it been down to Rakim, the song would have had more than one verse. "I wrote what, to me, was the first verse," he recalled, "and when I laid it down and we went back and listened to it, they was like, ‘Yo, that’s perfect! Front to end – that’s it.’ Especially at that time, I used to do four verses on a song. I was like, ‘Man, I ain’t even said nothin’ yet!’ But they were like, ‘That’s all we need!’ Certain things in the studio I liked Eric B for. Even just comin’ up with that beat [The Soul Searchers’ ‘Ashley’s Roachclip’] to put under the Dennis Edwards bass line [the ‘Paid In Full’ bass line is a replayed version of ‘Don’t Look Any Further’] was what I call brilliant. Sometimes his shrewdness helped what we was doin’. They had this cat that was supposed to be in charge of our A&R, but they kinda let us do whatever we wanted to do. And a lot of that was because Eric B told ’em, ‘Look, y’all can do this, but we gonna do the studio shit.’ And that certain shrewdness, some of that we very much needed, because I’m a very humble cat and, especially at that time, I’m not good to go up in an office and, you know, put ripples in the water. I was 16 years old, and I didn’t really care about the business at the time. All I cared about was writin’ rhymes."

While all this was going on, KRS and Scott La Rock were putting Criminal Minded together. The pair had met in a homeless shelter – Scott worked there, but to Kris it was home – and had made a couple of singles before settling on the Boogie Down Productions moniker and landing a deal with an independent called Rock Candy Records, who set up a hip hop offshoot, B-Boy Records, to market the group. Unlike Eric and Ra, though, BDP were not being presented with cheques for thousands of dollars.

"When we first came to B-Boy Records, or should I say Rock Candy Records, we signed a bullshit deal," KRS told me in 2010. "We knew it was garbage – we knew it. But we also were desperate people at the time as well, and we trusted. And underline that word ‘trust’. We trusted. We were in a room of men – and, matter of fact, not to make this any racial or ethnocentric, but we were in a room of black men: older black men, and here are younger black men, African-American men, tryin’ to sit down at a table to do business. I thought I was in good hands. We didn’t know we were signing our rights away because we didn’t know of any rights – we didn’t have any idea of what that was. But we knew that we were the workers and they were the employers. We knew that like we were the lowly artist that was making music for the big-time record company executive that was going to launch our careers and make us stars. And we would’ve done anything! If they’d said ‘Wash this car,’ we was washin’ the car. We had an arrangement between us. It was a fucked-up arrangement but we understood it, in that sense. It was street. It was straight street. It was, no real rules, no contracts that would be respected in that sense, and that’s what it was."

Scott would be presented as the album’s producer, though the record was created collaboratively, and involved more than just the two BDP principals. "Me and Scott grew up together, west side of the Bronx," Ultramagetic MCs founder member Ced Gee told me in the mid-2000s. "I knew Scott’s whole family. He was telling us about [BDP], so we got it." Ced was eventually given a "special thanks" credit, rather than the full co-production credit he had been promised by the B-Boy Records owners.

The difference in approach Ced Gee brought to the table was a combination of his own intuitive brilliance, and the availability of new technology that allowed him to channel it for the first time. The piece of kit in question was the E-mu SP-12 sampling drum machine, which started becoming available in 1986: Ced Gee was the first to use it to not just loop a sample, but to chop parts from the loop and then use them in a newly programmed sequence, using a technique known as quantising to time-stretch the pieces to allow them fit into a regular rhythm pattern.

"When the SP-12 first was out, a lot of engineers just looped," he said. "I was the first to take a sound and chop it up. Even if it wasn’t a full sound I’d make it sound full. If there was drums with a guitar lick on it, people would be like, ‘Oh, it’s got a guitar on – we can’t use it.’ I’d be like, ‘Why can’t we use it?’ And I’d hook it up – away you go! It works! On Criminal Minded, Kris would bring the record, I would take it, chop it, rearrange it [so it was] like the [original] record, but different. There were a lot of things that weren’t in the [SP-12] manual. I showed Paul C [legendary engineer, murdered in 1989, who worked on albums by Ultramagnetic MCs, Main Source and, later, Eric B & Rakim] how to make sounds sustain – how to take a guitar sound and make it full; how to make a horn echo. He showed me how to quantise quicker, or how sometimes you have to pan records – sometimes the drums or something would be clean only on one side."

Ced says he contributed production work to six of the album’s ten tracks. The ones he wasn’t involved in were ‘South Bronx’, ‘My 9mm Goes Bang’, ‘Elementary’ and the title track – the surprise there being that, given his description of the working process, he didn’t help with ‘South Bronx’, the track that appears to exemplify that method most strongly. The song uses horn stabs from James Brown’s ‘Get Up Offa That Thing’ which are twisted, re-played, redeployed in new patterns, and – at one point – pitched up and down before being sequenced into an entirely new melodic riff. "It was more me showing Scott how to use the sampler," says Ced. "Scott got that from me."

‘South Bronx’ was the record that launched BDP and put them on the musical map. Part history lesson of the block-party era and whistelstop tour through rap’s pre-history, the record included disses of MC Shan, KRS choosing to deliberately misconstrue Shan’s ‘The Bridge’ as having claimed that hip hop came from Queensbridge. Shan never said that, and in later years Kris would acknowledge as much: his plan had been to take pot shots at the man who was at the time number one emcee, and to use any resulting publicity to help get BDP a foot in the door. When Shan responded on an album track – ‘Kill That Noise’ – BDP must have thought all their Christmases had come at once. They replied with ‘The Bridge Is Over’ and BDP’s place in rap history was assured.

Public Enemy used competition to fuel their creativity too, but it would be years before the outside world found out about it. Already anxious about their LP sounding dated by the time the CBS machinery finally deigned to get it into shops, their mood was further darkened when Eric B & Rakim released their next single, ‘I Know You Got Soul’. Listening today, you can see exactly why anyone making rap at that moment would have had reason to question the validity of whatever they’d already got in the can. ‘I Know You Got Soul’ is an incredible record. Devastating in its simplicity – it’s just two samples (the drums and groans from the opening of Funkadelic’s ‘You’ll Like It Too’ in the left channel, chunks of Bobby Byrd’s ‘I Know You Got Soul’ in the right), an 808, and Rakim’s voice: but the record changed everything.

In part this is because of some clever, if largely intuitive, sonic decisions. Listen to the Bobby Byrd track and you’ll hear a burbling, circular bass line: this is absent on Eric and Rakim’s track because the sample is looped at a point before the bass line resolves the first half of the phrase. The second shoe never drops. The result is a reconfigured part-riff that sounds like it’s continuously tumbling over itself, or is on the edge of losing balance. Moreover, the Funkadelic drums and the Byrd drums are both very similar loops, both played with great regularity by fine funk drummers, but they’re not identical so they rattle and fizz, as if about to fly out of time with each other. Listen, too, to the quieter portions of the track, and you can hear the looped drum sample leaking from Rakim’s headphones into his mic in the booth.

And then there’s Rakim’s vocal performance, which still sounds jaw-dropping today, but back then was inconceivable. Here was an emcee approaching the job of rapping with the same sense of invention and avoidance of musical cliche of a jazz soloist. Each line finds him using new rhythms, locating new places in the beat to drop syllables, allowing himself to slow down and speed up through different phrases. On this record, it was no longer relevant to ask who Rakim’s inspirations were among emcees: instead, you were more likely to hear the antecedents of his flow when listening to Fred Wesley’s trombone break on the Bobby Byrd 45 he and Eric had sampled.

Lyrics, too, were key in separating these three albums from the rest of what was going on in rap. Each record dwelt on a few established tropes, perhaps mindful to give the burgeoning hip hop audience a way in. Oddly, perhaps, when considering how their music would later be viewed through a political prism, it’s Public Enemy’s debut that is in some ways the most conventional when looked at as an example of mid-’80s rap. The opening track and second single, ‘You’re Gonna Get Yours’, is a song about cars, and enjoying looking cool while driving them: sure, there’s a way of taking that which can be construed as political, but as a theme in American pop it’s established, not revolutionary. ‘Sophisticated Bitch’, a low point in the band’s discography, is a trite and stereotyped view of gender-relationship dysfunction; ‘Public Enemy Number One’, for all its formal daring and studio boundary-pushing, is, at the end of the day, a declamatory declaration of emcee pride and potency. That’s not to say that the record is without its moments of real technical or writerly innovation – and in the brilliant ‘Rightstarter’, these rhythmic and poetic developments are allied to a clear sense of political purpose (listen to the way Chuck attacks the line "Don’t ask how we act the way we act/without lookin’ how long you’ve kept us back", and hear both the technical and literary invention that would soon see him hailed by his peers as the greatest rapper in the world).

KRS may have been relying on syncopated patterns and bouncing syllables more on Criminal Minded than he would do later – certainly, his work here is very much an early study when compared to the dazzling verbal gymnastics of an ‘I Get Wrecked’ or even the limber dexterity of an ‘MCs Act Like They Don’t Know’. And he, too, is often content to hymn his own abilities rather than to try to use his platform to say anything truly substantial. Yet there are moments, even in Criminal Minded‘s proving grounds, where both lyrics and delivery reach transcendence. ‘Poetry’ was a shock in ’87, KRS fighting for rap’s legitimacy as literature with a performance that combines surgical precision with dexterity and wit. Mastering the skittering beat with ease, insinuating lines in between the jagged slashes of Scott’s scratching, it’s a track that was at once challenge and boast: hear how he switches between styles and deconstructs the rhythm as the lyric flips from "KRS-ONE means simply one KRS/That’s it – that’s all – single, solo: no more, no less" and in to the following, more conventional "I’ve built up my credentials, financially and mental". And then, of course, there’s ‘9mm Goes Bang’, an unprecedented vision of the rapper as actor, the lyric situating the listener inside a story told by KRS in the first person, the violence and the motivations of the character he creates as disturbing as the actions the narrative depicts – especially when allied with the portentous, echoing reggae track.

Of the three, Rakim takes the gold in terms of both style and lyrical ingenuity, though his work on Paid In Full benefits from less of a thematic range. These are all ultimately paeans to his own skill as an emcee – or to Eric’s DJ-ing – but it’s how he chooses to address this more limited subject range that reveals his incredible advances in the art of writing and delivering raps. He has an eye, even in his teens, for the indelible lyrical image. In the title track we hear him referring to money as "dead presidents", a motif that would proliferate through rap and beyond (eventually turning up as the title of a film about a black Vietnam veteran). The celebrated vignette in ‘My Melody’ where he battles three groups of seven emcees – referencing his involvement with the 5% Nation of Islam and the group’s interest in numerology – was another moment where he set himself a long way apart from his peers. There are gems throughout the record, though: from ‘I Ain’t No Joke’s "I hold the microphone like a grudge" to ‘As the Rhyme Goes On’s "I draw a crowd like an architect", it’s clear this is someone who thinks about words and their meanings in ways entirely new to hip hop. Then there’s the unprecedented use of flow, where internal rhymes and rhythms are deployed to transform the music rather than merely ride the beat: in ‘My Melody’ we not only get the exceptional "My unusual style will confuse you a while" but at the end of the short, third verse, Rakim’s writing goes up another level in complexity:

"Rhymes are poetically kept and alphabetically stepped

Put in order to pursue with the momentum, except

I say one rhyme and I order a longer rhyme shorter

Now pause, but don’t stop the tape recorder"

"In ’87 Rakim and KRS-ONE changed the whole game of rhyming," Chuck D said. "Rakim was able to look at a fast tempo and slow it down to his poetic pace. KRS-ONE did the same thing. They slowed the music down to them, rather than trying to jump with the music. Before, if you raised the beats per minute, the rhymes had to jump to the BPM. Rakim was like, ‘Fuck that’. The rhymes would space over the beat."

The impact these records had on fans was immense, but perhaps there was no greater measure of their influence than what each artist’s releases did to their peers. Certainly, in the case of ‘I Know You Got Soul’ and ‘South Bronx’, Public Enemy – with an album just released that they felt was already out of date – were stung into (re)action. Chuck was not going to be content to sit waiting, while these two groups – one of whom they shared a manager with – redefined the possibilities of hip hop records.

"Eric B’s camp, especially Ant Barrier – Eric B’s brother – used to give us hell!" Chuck recalled. "’What’s all this talk about they signed with Def Jam? Chuck sounds old!’ We was like, ‘Damn! It’s only because the shit is out-dated a little bit!’. But it wasn’t just Rakim: Scott La Rock, Ced Gee and KRS-ONE changed the whole game. When Kris came out with ‘South Bronx’, he tells the world: ‘I’ve got a different style’. So here we were, wrapping up an album deal, and these two 12"s changed the whole thing. We had this little niche in February and March where we were able to put out ‘Public Enemy Number One’ in February – Black History Month, 1987 – along with [b-side] ‘Timebomb’, then the album comes out in April, and we think we’ve got something we can release as a second single. Then ‘I Know You Got Soul’ comes out in the April – and what we really thought was, ‘This is some shit that revitalises and changes the way we do records!’ ‘I Know You Got Soul’ was the best fuckin’ record I had heard in my fuckin’ life, and it comes from Eric B who was givin’ us hell! We were gettin’ ready to go out on the Bigger & Deffer tour [on which PE and Eric B & Rakim supported LL Cool J], and we’re gonna have to look at the guys every day who made this fuckin’ record! I was, ‘No, man!’"

The one-two combination of ‘South Bronx’ and ‘I Know You Got Soul’ hit PE like a heavyweight’s knockout blow. But instead of throwing in the towel, the group returned to their corner and came out for the next round swinging. The track they created in response would make Public Enemy’s name, and change the history of rap music in an instant.

"We realised we had no singles that fit this new style of music," Chuck said. "So we went to the lab, right before we rolled on the Bigger & Deffer tour in ’87. Flav played the sampler – it seems to be [James Brown’s] ‘Funky Drummer’, and it’s the ‘Funky Drummer’ sounds, but he played them. There’s some Trouble Funk in there, and hidden inside ‘The Grunt’ [a then-obscure 1970 45 by Brown’s backing band, The JB’s] there’s a little bit of Miles Davis: I forget the exact record. We recorded it at the PE HQ in Long Island, then I took the tape back to my moms’ house and locked myself in that house for a day, with the number one mission in my head that it has to be as good as, if not better than, ‘I Know You Got Soul’. I was writin’ to it, playin’ it on a little radio, and my moms thought it was a tea-kettle going off. She was, ‘You got some tea on the stove?’"

‘Rebel Without A Pause’ would arrive too late to make it on to Yo! Bum Rush The Show, but PE thought they could make up the lost ground against Eric B & Rakim and BDP if they could include the new song on the b-side of the second single from that album, ‘You’re Gonna Get Yours’. Russell Simmons turned them down, arguing that a new track on a b-side would distract attention from the album the single was being released to promote. Chuck tried a workaround, approaching sympathetic Def Jam staff directly, urging them to take the master tape and include it on the single. That didn’t work: so, still needing Russell’s approval before it could be added to the release, Chuck and Hank drove to John F Kennedy airport, where their manager and label boss was about to take a flight to the UK with his brother’s group (and his management company’s biggest stars), Run-D.M.C.

"On the runway before he was gettin’ on the plane we was askin’ Russell, but Russell was still sayin’ ‘No’," Chuck said. "Run was behind him, with [Jam Master] Jay, so we asked Run and Jay, ‘You man, damn, you know – I’m just tryin’ to ask your brother, how’s this gonna hurt the album?’ And Run just stopped, turned, and said: ‘Yo, do it’." Apparently, one Simmons’ word was as good as another’s, and the track was added to the single.

"It was one of those rare cases when I knew a record was a record," Chuck said. "I can’t even name another situation where I made a record and knew. I said, ‘I could die tomorrow, and this muthafucker’s got a life of its own’. I can’t explain it. This was the next shit that went past ‘I Know You Got Soul’ – which was a very hard record to fuckin’ top! But our whole thing was, it might not have been better, but it was harder, faster, stronger: it fit us, it did things, it said things, and it had the right phrasing in it that was developed by Rakim and KRS-ONE."

The summer of 1987 proved a watershed moment for this still-new music. ‘Rebel Without A Pause’ quickly moved from its limited availability as the b-side of the second Bum Rush single to becoming a single in its own right, and PE took its noisier, punkier sonic direction as the jumping-off point for the sound and style that would characterise their second LP, which would be hailed as one of the greatest albums of all time. Eric B & Rakim were clearly influenced by PE, just as Chuck’s group had been spurred on by them: their second album, Follow The Leader, boasted angry, chaotic soundscapes and, with its title track, took hip hop off into the multiverse. BDP’s development was perhaps the most measured of the three, in no small part because of Scott La Rock’s murder in the autumn of 1987, which still remains unsolved: KRS kept the group’s name and put out By Any Means Necessary in ’88, keeping the three bands in lock step on the release front. The holy trinity of hip hop would continue to drive the music forward throughout its ’86-’92 "golden age", and all would make better albums than their debuts: but without these records, and the way each artist spurred the others on to their next big breakthrough, none of it would have been possible.