“Being ahead of your time is worse than being behind your time if you want people to have some context for it”, John Foxx has told me. “Things moved quickly back then.” If you put it to Foxx that the problem early Ultravox! faced was that they were post punk before punk had finished saying its piece, he laughs, “We were “pre-punk” before punk had started too! People weren’t ready. We were listening to Roxy Music, Bowie, Krautrock… we had a wider palette. But punk broke barriers, and they needed to be broken.”

We don’t think of Ultravox! as a punk band. We tend to think of the later Ultravox, without the exclamation mark and with Midge Ure vocalising in windswept, homage-to-Leni-Riefenstahl videos, as New Romantics more than anything else. They’re a little harshly sneered at, thanks to Ure’s uncool Band Aid associations, even though the Scot was at the heart of many prime Eighties things, from ‘Vienna’ to Visage. And that band’s albums contain some mighty Euro-synth salvos. But the original, Foxx-led, Ultravox!, with that overzealous exclamation adopted as a homage to Neu! before Neu! were fashionable, were a very different beast.

Their first two albums arrived with indecent, hungry, eagerly creative haste, within eight months of each other. Island released their self-titled debut in February 1977, the follow-up Ha! Ha! Ha! in October. At the time they seemed impossibly, romantically, futuristic. Forty years on they sound impossibly, romantically, futuristic. Nick Rhodes (even a stopped clock, etc) has said, “Ultravox were the link between punk and what came next. Everyone should own the first three Ultravox albums.”

Does John Foxx hear this music from the distant past and wonder how it was so prescient? Does he hear its obsession with sex and machines and artificiality and living deaths and fear of apocalypse in the western world and ever think: how did I know that then? How did I see the future?

“It does happen”, he muses. “But it wasn’t surprising to me at the time. The whole thing seemed quite normal and I couldn’t understand why other people didn’t get it. I thought: maybe I’m on the wrong track completely. I thought that often. Maybe I was, but you just have to do what seems right at the time. And oddly enough, things turned out well. There’s a lot of instinct involved in music, isn’t there? You can’t really determine if it’s logical, or else it’d get awfully dull. So you have to take chances. And you do that when you’re young, because you don’t give a toss, you’ve got nothing to lose.”

The albums do sound like the work of ebullient youth; peripatetic and hyper like many of the best debuts. Musically they’re almost TOO keen to make an impression, but this is counterpoised by Foxx’s lyrics, jaded to the point of existentialism. These too are hectic, busy, tumbling over themselves with a quantity that could in lesser hands trip up the quality. Satchel-fulls of teenage notebooks appear to have been emptied herein. Counter-intuitively, they’re in structure – but not content – reminiscent of Springsteen’s first two albums, where a very different kind of writer threw couplet upon couplet upon couplet in the hope that something among the florid imagery would stick and prove his undoubted sincerity. He was, in time, to take the tried and trusted less is more path. Foxx, of course, took that path too, and then some, into minimalist electronica. But in ’77, hey hey he was art-punky, and he’d got something to say. He remains, curiously, Vincent Gallo’s favourite lyric writer of all time.

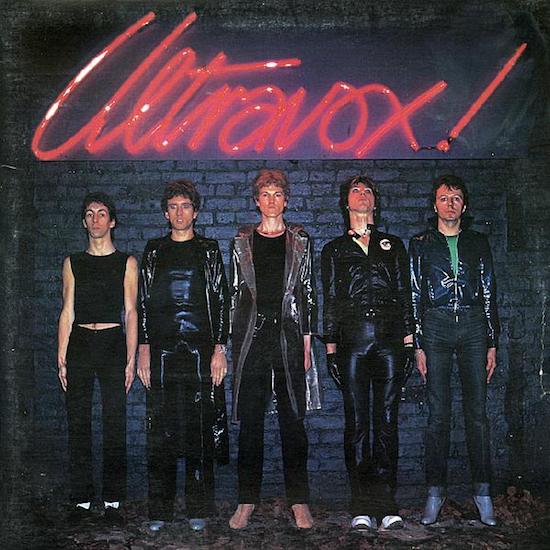

The first album, co-produced by an impressive line-up of Brian Eno (Foxx had loved Another Green World), Steve Lillywhite and the band, is clearly a product of a diet of literate Bowie and glam with a minor strain of punk aggression. Photos from the time – and remember that even supreme sultans of suave Japan went through the “awkward wardrobe” years – show five young men not quite sure whether to dress glam or punk. The sneer of the latter feels a little glued on, as if they knew they were supposed to be more angry, less poetically reflective.

By the second album – produced by Lillywhite and the band – they’ve become more at ease with being their unique selves, and are letting a little Krautrock and motorik in. Yet they’re still sort of trying to rub along with the reductive, snarling, in-your-face punk trends: they’re just so smart and intellectual that they can’t help being a little out of step. As so often with art that endures beyond its peers, it’s that sidestep, that move to the left, conscious or otherwise, that keeps it interesting. By the third album Systems Of Romance, a year on, they were fully embracing dark electropop in Germany with Kraftwerk colleague Conny Plank: indeed thereby influencing a wave of bands themselves. Arguably, that record, the next chapter, was more influential in real terms than these first two – Gary Numan hadn’t happened yet – but as unwitting outsider art their filmic fervour fascinates.

“There’s something about being young that’s all to do with showing off, and overdoing things”, Foxx told me. “Except you’re not really overdoing things, you’re doing things just right for your age and time. But then (after that) you must avoid, as an artist, the terrible trap of imitating your former self. For me that’s one of the cardinal sins. You must refine, and keep an eye to the future, and not look back too much. See where you can go with what you’ve built. And leave it to other people to adapt and adopt and change and steal and perfect whatever you’ve done in the past. If you’ve said “I want to be a machine” in the past, you don’t need to say it again. It’s implicit.”

John Foxx, of course, is not real. Dennis Leigh is John Foxx. Up to ’79 he inhabited the role within Ultravox!, then took it with him. He was at the Royal College of Art when he formed Tiger Lily, who morphed over time and via a few personnel and name changes – they were briefly called The Damned, before realising it was taken – to Ultravox! (They only decided on this when the debut was mostly recorded). The album showed their Roxy Music and Cockney Rebel leanings, also acknowledging a love of The Velvets and Iggy, not to mention Foxx’s strange personal fondness for The Shadows – but also displayed a penchant for the cinematic (Fritz Lang, film noir). This giddying versatility could emerge as anything from cod reggae (‘Dangerous Rhythm’) to lengthy narratives which made the lyric sheet of Diamond Dogs look like it was only half-trying. Foxx regaled us with tales of losers, users and abusers on such titles as ‘Life At Rainbow’s End (For All The Tax Exiles On Main Street)’, ‘Saturday Night In The City Of The Dead’ and ‘The Wild, The Beautiful And The Damned’. Oh. After forty years I’ve just realised that last title is probably why I make that bizarre correspondence in my psyche between young Foxx and young Springsteen, who of course gave us ‘The Wild, The Innocent & The E Street Shuffle’. Plus at least Foxx managed to work “the damned” in there somehow, tipping a hat also to the name of the second Jazz Age novel by F. Scott Fitzgerald, of 1922. While nobody would suggest that the punk rockers related to upper-class flapper girls doing the Charleston, there’s a kinship to be perceived between two generations of youth who saw themselves as uniquely significant, and able to offer viable protests against ennui and doom.

We must praise the rhythm section of bassist Chris Cross and drummer Warren Cann who, throughout, enable challenging shifts from ruddy-cheeked and robust to robotic and restrained. Stevie Shears (guitarist) was gone by the third album but everything he does here adds character to the movie. And Billy Currie’s keyboards and violin, often taken for granted throughout a durable career studded with great moments, are chilling and beautiful.

John Foxx, or Dennis Leigh, explained back then why he’d changed his name. “John Foxx is more intelligent than I am, better looking, better lit”, he declared. “A kind of naively perfected entity. Like a recording…where you can make several performances until you get it right…or make a composite, then discard the rest.” Well, you didn’t get that kind of quote from The Cockney Rejects.

“I remember that”, he smiles in modern times, “but can’t remember exactly when I said it. I think there’s a point where you don’t know what you’re doing, you just do it because it feels right. And inventing someone else…you don’t question it, you just do it. I didn’t “think” about it much. Initially I did it so I could separate my private life from it. I didn’t want to sign myself in at a hotel as Leigh, in case I became recognisable. A fail-safe, to pre-empt anything like that. As it happened, I needn’t have worried, ha ha!”

Indeed sales figures for these two tremendous albums were pretty dismal. And his announcement that he was eschewing emotions – wanting to be a machine, as the song states – made relationships within the band taxing. (You have to have some degree of sympathy with the rest of the chaps there: it must have made letting off steam quite difficult). Nevertheless, the identity, the persona, was crucial to his writing (not to mention the gruelling touring): “It does have a value. You can blame things on someone else. You have a scapegoat. It becomes quite schizophrenic, but it’s dead useful as well. It still confuses me sometimes! But it’s a…construct. You gradually realise that bit’s too big, so you chip a bit off. You’re building something, and you can change it if you want, so it’s not like surgery. More like sculpture.”

“Ballardian” is now –understandably – a chronically over-used reference, but there was much imagery within Foxx’s lyrics which suggested a familiarity with the author. Suburbs. Maps. Silent movies, dead boulevards. Jukebox mongrels, lonely hunters. Frozen dawns. Automats, skyscrapers, high-rises and “electroflesh”. This last appears in the extraordinary ‘My Sex’, where he twists Brel’s ‘My Death’ and describes the vulnerability of the body: “a fragile acrobat”. In ‘I Want To Be A Machine’, he pleads “free me from the flesh”. Billy Currie’s accelerating violin becomes a beacon crying in the dark. On some tracks, Ultravox! are just a very good rock band with added synths and violins, but on broken-down, bereft, post-emotion ballads like these, they’re in touch with the timeless.

Ha! Ha! Ha! is a crying game of two halves. There’s the ferocious – the lead single ‘ROckWrok’ (sic) is as sex-mad as ‘My Sex’ was sex-fearing: the lines “c’mon let’s tangle in the dark/fuck like a dog, bite like a shark” somehow got onto Radio One, so mangled was Foxx’s delivery. There are other “punky” sprints, litters of feedback and screech, which you suspect were encouraged by Island. “We were trying to increase bass frequencies for the synths, subsonic zooms”, Foxx said once. “We wanted to work like sonic terrorists…to make audiences sick.”

However this is also the album that gave us the suspense and flawlessly restrained drama of ‘The Man Who Died Everyday’, the yearning of ‘Distant Smile’ and ‘While I’m Still Alive’, and above and below all the masterpiece ‘Hiroshima Mon Amour’. Credited by some as the first synthpop or “New Wave” song to emanate from the supposed rock arena, it took its title from the 1959 Alain Resnais arthouse film (Foxx hadn’t then seen it, just liked the name). It took its sound and feel from God knows where. Cann and Currie magic up a mesmerising mood with a Roland CR77 drum machine; Gloria Mundi’s C.C. contributed the countering warmth of the heartbreaking saxophone. Foxx, who’d had to succumb to shouting elsewhere on the album, gave here his most fully realised vocal – a cryptic croon, one for the ages. All those early, epochal Eighties marvels of synth and (controlled) sentimentality, of melancholy and perpetual motion, hark back to this. Ultravox! had hit on their moment of epiphany, moving in monochrome, and dropped that exclamation mark to follow their new true faith. They were Europeans.

“At that time there was a lot of interesting science fiction about abandoned cities, and it all worked together. It’s a recurring theme of mine, the future dystopia – well, not just mine, lots of people do it. I always enjoy films where half the world is abandoned or overgrown.” Foxx was to abandon this world – five years of touring burned him out. “I’m not built for that: it’s like a psychic drain”, he told me. “Your perceptions get a bit out of kilter. I’m not a good rock star, in that sense. I moved towards the tranquil”.

Four decades on, the early Ultravox! utterances sound like the music of a temporarily great rock star, who, with a band who were patently and latently overqualified, was fantasising himself into being. They were ahead of their time, and out of it.