The first thing you encounter upon entering the gallery is a sign, roughly A4 in size, type-written and framed. Beneath the gallery address, exhibition title (‘Civilization?’), and dates – all neatly aligned in the top left corner, like a formal letter – the text begins: “I propose to install a group of artworks at Kate McGarry Gallery at the above address. The artworks in question have their origin in the psychological phenomena known as pareidolia; in which a person takes seemingly random objects or naturally occurring phenomena and attempts to make sense of it by making the scene of object in front of them into something significant.”

“The most common reaction,” the text continues, “is to see a face, animal or the subject revealing a hidden message within its form.” The author’s name has been typed in the bottom right-hand corner of the page. There is no signature. But despite the frame, we can detect the creases where the sheet has been folded twice in order, presumably, to fit into a standard sized envelope.

Pareidolia is a species of apophenia, “the spontaneous perception of connections and meaningfulness in unrelated things.” The definition comes from William Gibson’s novel Pattern Recognition, from a passage in which the protagonist, Cayce, begins to worry that the links she is making between the bizarre phenomena happening around might be just that, “an illusion of meaningfulness, faulty pattern recognition.”

There’s something inherently Gibsonian about these twinned tendencies. Writing at the very beginning of the twenty-first century, he was already able to sense the incipient paranoia of networks. Just last spring, the American science fiction author was tweeting about a Japanese museum dedicated to rocks that look like human faces. “Pareidolia paradise,” somebody called @GregStolze replied. Since the development of Google’s DeepDream program, even computers have pareidolia now, spontaneously finding doggy faces in almost any image.

But Leonardo Da Vinci recognised its potential for artists half a millennium ago. “If you look at any walls spotted with various stains or with a mixture of different kinds of stones,” he wrote, “if you are about to invent some scene you will be able to see in it a resemblance to various different landscapes adorned with mountains, rivers, rocks, trees, wide valleys, and various groups of hills. You will also be able to see divers combats and figures in quick movement, and strange expression of faces, and outlandish costumes, and an infinite number of things which you can then reduce into separate and well conceived forms.”

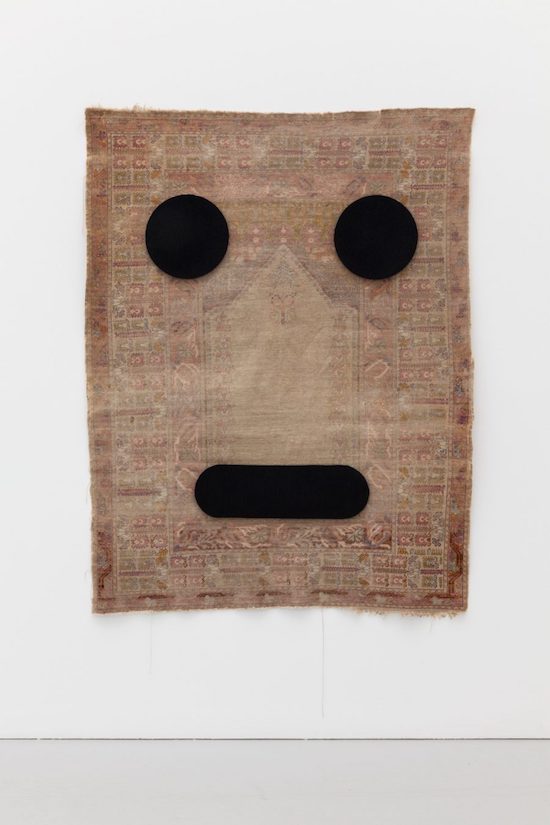

Peter Liversidge, Carpet Face #2, 2017, Courtesy of Kate MacGarry, London. Photos Angus Mill

Look up Apophenia on Wikipedia, scroll down to the subheading ‘Pareidolia’ and you’ll see a face on the right-hand side of your screen. Or rather, you wont. What you’ll see is a circle, and within that circle two smaller circles and a line beneath. What you’ll perceive is a face – not unlike the “smiley face” many people perceive in pictures of the Galle Crater on Mars. This figure is all over Peter Liversidge’s current show at Kate MacGarry.

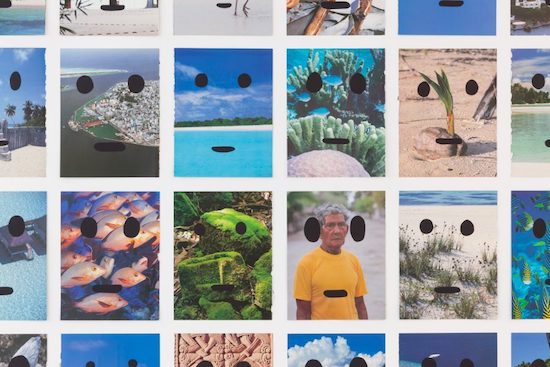

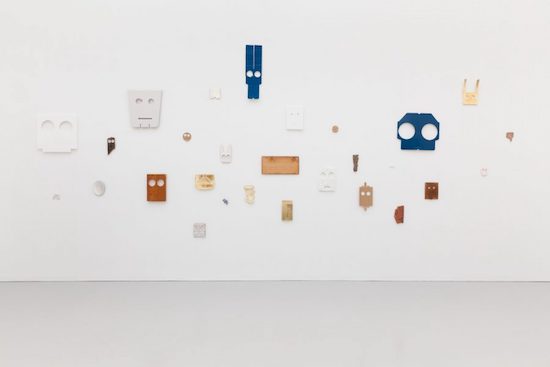

There’s a nine by four grid of portrait oriented, postcard-type images of the Maldives, with the vaguely face-like twin rings and a dash overlaid over each, in black felt. Worn old rugs hang from the walls with the same soft cloth accoutrement. On a far wall, flattened boxes, empty food packets, hunks of drift wood, crushed polystyrene cups, loads of them, and each punched through with two gaping holes and sometimes a slash for a mouth.

It’s hard to stop oneself from attributing personality to each of these pseudo-faces. Does the paler, more worn rug look somehow sadder than the others? And amongst those Portraits of the Maldives, isn’t that speedboat making an enigmatically cocked eyebrow over the left ‘eye’? Isn’t the sail of that yacht making a funny sort of nose there?

And yet these appliquéd attributes, our felt spots and slashes, are not “seemingly random objects or naturally occurring phenomena”. They were put there, clearly. Or at least, most of them were – on the far wall, there are one or two wooden husks whose eyeholes seem to be naturally occurring. Are all the other works here just a set-up to prime you into seeing faces in just these few? In some ways, Liversidge’s installation seems less like an investigation of the phenomena than its parody (and the presence of that face-like figure on the Wikipedia page seems to me to add some credence to this suggestion). Is he taking the piss? Well, maybe…

Born in Lincoln in 1973, Peter Liversidge has spent some twenty years writing similar proposals, each one typed up on his Olivetti Lettera 35. Caught somewhere between Fluxus event scores and the conceptual art of Sol LeWitt, they range from the childishly simple to the extravagantly impractical.

“I propose to bruise all the apples in all the shops in London,” he once typed out, for a show at the Whitechapel Gallery in 2013. “I propose we stand in the breeze,” for Helsinki’s Museum of Modern Art in Helsinki 2011. He once invited three drummers to play the same beat in the galleries of the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art. He has filled Bloomberg Space with the smell of freshly cut grass. One time, he had Florence and Richard Ingleby, proprietors of Edinburgh’s Ingleby Gallery, swap clothes for a day.

“I think I am not interested in the idea of instructions,” Liversidge once said, in an interview with Daniel F. Herrmann from the book Selected Proposals. “My proposals are really invitations. It is about initiating a process of which I don’t quite know the outcome.” In this sense, there is some common cause with John Cage, who defined experimental music in terms of “an act the outcome of

which is unknown.” But like Cage, for all the seeming anarchy and arbitrariness, there are certain recurring phenomena, certain recognisable traits: white bunting, words in lights – especially the word “hello”.

Peter Liversidge, Civilization?, Kate MacGarry, 2017, Courtesy of Kate MacGarry, London. Photos Angus Mill

Some of the more intriguing of Liversidge’s proposals are those that directly address the materiality of their own process of production. “I propose to commission a painter to paint a copy of this typed proposal” was his entry to the John Moores Painting Prize in 2012. In 2008: “I propose to film the typing of this proposal. The resulting film will be shown from beginning to end, projected directly onto the wall at Centre d’Art Santa Monica at a size no larger than A3. The film would be on a continuous loop.” For his Whitechapel show, he proposed to go out in the streets and graffiti the walls with every typo he had made while writing the proposals. As with LeWitt, the idea – and its setting forth – becomes a machine to create the work.

Liversidge’s proposals often border on the absurd and impractical – even the impossible. I do not believe he ever realised the proposition to demolish the buildings opposite the Whitechapel Gallery and build in their place, from the basement up, an exact replica of the gallery itself. But my favourites are the poetic – “I propose that there is a silence out there” – the unabashedly romantic – “I propose to take your hand and guide you through the exhibition” – and, best of all, the ones that fuck with history.

“I propose to place a fake archive for an exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery from some point in it’s past. The archive would take the form as the others in the Galleries current archive. The fake archive would be for a group show and would document all the artists and collect associated ephemera; photographs, curator notes, invitations to artists, poster & private view cards etc… The fake archive would take it’s place, by date and size in the current archive. It would be boxed as the others around it and would only be available to view by making an appointment with the Whitechapel Gallery archivist Gary Haines.”

I don’t know for sure whether this particular proposal was ever actually realised. But as far as I can gather, Gary Haines is no longer the archivist at the Whitechapel Gallery. I must admit I rather like the idea that whoever now is in charge of the gallery’s records, no longer has any idea which of their past exhibitions might be fake.

Peter Liversidge is at Kate MacGarry until 18 February