Photographs courtesy of Clara Wildberger

There could barely be a better figurehead for Belgrade’s simmering multi-limbed music scene than Jan Nemeček. Born in the city back in 1989, the Serbian artist has already ventured into a sprawling variety of electronic styles and genres, releasing music via an unwieldy mix of netlabels, tape labels, and his own bandcamp page. Over the years he’s turned his hand to UK garage influenced productions, sprawling minimal techno, meticulous instrumental compositions, and most recently a pounding live modular set – which I got to check out at this year’s Elevate Festival in Austria’s second city Graz.

At this year’s edition of the festival there was an abundance of artists seeking to energise their live electronic sets in any way possible. Cid Rim (solo project of Dorian Concept drummer Clemens Bacher) focused in on rabid breakneck drumming over complex backing tracks, while R&S records’ Lone (aka British producer Matt Cutler) rearranged housey tracks to go with his own live drummer plus live projections from visual artist Konx-om-Pax. Conversely, in a full body suit of white hoodie and joggers, Justin Broadrick’s JK Flesh project pulled an utterly insane set out of little more than his laptop and a MIDI trigger, building on the severity of the tech-noise on his recent Rise Above album. Broadrick mostly nodded along and angrily twiddled knobs, letting the brutal tracks and strobe lights do the heavy lifting through a blinding performance. Nemeček met these differing methodologies in the middle, improvising a grinding beat-heavy set out of his modular setup (similar to his recent Emergence recordings). He managed to maintain the effect of an artist huddled behind gear, summoning a web of spontaneous ideas, that were nonetheless imbued with live energy and danceability. Much like the steady change of his home city though, Nemeček’s germination from electronica fan to an experimental musician with endless potential has been a gradual one.

While he mostly utilises the mainstay tools of synths, beats, and samples, Jan Nemeček manages to deploy them in consistently unexpected ways. His eclectic fingerprints are probably most audible on his otherworldly self-released Fragmented album from 2014. Created in a brief period applying intense granular editing to a vast body of samples, the album seemed to hint at what would get called into existence as Future Grime the following year by Visionist. It also mirrored the emergent meticulous instrumental cyber dreams from the likes of Tim Hecker or Arca, jettisoning the occasionally aimless drift and impressionistic grandeur of 20th century ambience, producing rather a micro-detailed music that reveals moulded layer after layer with each listen.

The young artist has slowly started to receive recognition outside of his home country, helped along the way by international projects and festivals such as Elevate, or increasingly important Serbian festivals such as Exit (where he once performed at the upstart age of 17), not to mention Resonate (which he has also helped to curate). Ahead of his set at Elevate, I met up with Nemeček in Graz’s foliage paradise of a main park to discuss his myriad processes, life in Belgrade, his Dad’s history as a Yugoslavian acid rock pioneer, and the future of Europe’s increasingly institutionalised electronic musicians.

What do you think about the way in which the many musicians – many artists generally in fact – increasingly craft their output towards something that they can put in a proposal to a funding body? Or even perhaps the way ‘club culture’ has become an art form to be scrutinised and analysed in this way?

Jan Nemeček: Well, at least it’s something I could actually participate in! I’m fan of deconstructing stuff in clubs, and nowadays when you don’t really have so many expectations going into a club. You can even get surprised if it’s just a techno night, only four to the floor techno. It was definitely a huge turning point when I realised you can do whatever you want now with these club tropes. I had the realisation – which I thoroughly enjoyed – that you can just basically take noise, or any kind of experimental music, and put some kind of kick or upbeat hi-hat, and everyone thinks it’s dance music. This has been my new [makes air quotes] ‘club set’ basically – taking my samples and noises and just trying to make them sound clubby. And it’s worked… I think.

So you’ve been making music for about ten years by now, since you were about 17 or thereabouts. What were you doing when you got started back then?

JN: Well I count my first live performance as the beginning, although I was dabbling obviously before that. I didn’t really have much of a social life. It’s a really strange thing for a kid to be listening to cheesy rock bands from the 70s, spacey stuff like Tangerine Dream. To be fifteen in Serbia and listening to Tangerine Dream and Klaus Schulze – it’s not a regular mindset! That kind of broke me in a way, and I spent three years or so chasing the idea of doing a spacey concept album. That got me started. My parents were very supportive and got me a synth which I recorded and multitracked and all that. Those years got me the technical chops to record and edit. It wasn’t that I was very good at it – I just enjoyed doing it! It was about leaving the recorder going for thirty minutes, playing some spacey jam with a phaser effect on, and thinking I sounded like fucking Jean-Michel Jarre.

Eventually though, the practical element sunk in that I was not going to be able to perform this live.

Because of all the multi-tracking?

JN: No, more because it’s pretty much unlistenable! Nobody wants to listen to spacey jams with phasers! At least at the time that’s what I felt. And then I got introduced to minimal techno which was huge at the time; in like 2005-2006. The really minimal, really boring side of minimal techno – those Richie Hawtin mixes and all that.

The experience of 00s minimal techno and 70s space music is pretty similar really – in terms of the effect they were trying to create. They even had the odd spaceship on the cover.

JN: Yeah, that kind of clicked for me, that it was basically the same except they were focusing on the clicks and beats a bit more, but that there’s still this space so I could really work with it.

I definitely see you as having two very distinct sides. I saw you play at a club called The Tube in Belgrade, and that was a dancey live techno set done using your computer. And that’s so different from this other side of you, featured on the Fragmented album, or the Organ Hell stuff.

JN: Well a lot of the whole clubby side emerged from this collaboration I did with my friend Goran called Brickwall Brigade. We did three EP’s worth of tunes when it was the peak of the UK, garage, dubstep thing. But we never really clicked with that crowd or did a proper release, and it was just this trove of material. I actually eventually repurposed some of it into a techno live set, ‘cuz you realise that even though it was written at 140bpm or some dubstep tempo, that if you just change the kicks or the tempo it can perfectly work at like 120.

Then every two years or so I get the urge to sit down and do a more ‘proper’ album. Stuff like my Emergences releases is more of just a demonstration with some live takes, but Fragmented was more like I sat down and hyper-edited this thing. It would be impossible to do live, it’s very much computer music.

I was completely blown away when I heard Fragmented – it’s so meticulous.

As it was two years ago now, I have this distance to it, and I don’t really remember how I did it now. When I hear it, it sounds like it must have been edited for such a long time, but I don’t even remember doing it. I feel like I don’t know how to top it! It sounds horrible and pompous of me… but I don’t really even feel like I did it. Not to say there’s a higher power or some kind of bullshit like that. I don’t think I have the patience to repeat it either. Also, sampling was a huge part of it – in fact it was pretty much all constructed using samples.

What were you sampling?

JN: I shouldn’t say… But it doesn’t really matter. I even drop hints just for fun, in the track titles or whatever. In the end though, it doesn’t matter. It’s so granular, you just get whiffs of it; disembodied vocals wrapped in reverb which you can’t identify so much.

So what are you recording currently then?

JN: Mostly just these single take modular recordings, like the Organ Hell EP, which still has the dates and draft titles of the recordings [e.g. ‘20160330 (Sines)’]. Maybe 2016 will just be my ‘archival year’ – just get it out on bandcamp!

That’s another trend, questioning what is a ‘legitimate finished album’, and what’s just a ‘release’. Take Anthony Child’s modular albums recorded in Hawaii – as great as they are, they don’t have the meticulous feel of a Surgeon album. At the same time, Kanye West went ahead and reworked Life Of Pablo after he’d already released it!

JN: Well I love both albums! Both in my top tens of their respective years. But yeah – it’s a technical challenge to work on this kind of music, to really layer everything. And people do it less now. A good example of somebody that does it is probably Tim Hecker, who works away on his tracks, adding intricate layers …

… and now nobody likes him and everybody thinks he’s pretentious!

JN: Well – that’s perhaps for different reasons! But it’s become rare. A lot of this modular techno stuff is just people plugging everything in, recording for thirty minutes, and then that’s it, we have a track. And it’s nice too! Having Bandcamp and direct contact between artists and listeners. It’s nice to just put up a recording and have people buy it.

The modular synth is sort of a solution to this problem of how to make ‘Live Electronic Music’. You could see last night here at Elevate, that’s what all these electronic artists are trying to do – to make it more of a live experience, and thus also to make it more palatable.

JN: Yeah, it’s one of the last one-person-on-stage things you can do, to make live electronic music. I’ve really had this crisis so many times. I redrafted Fragmented tracks so many times, I even did a few with a vocalist, but then it really feels instantly like something that can be played on the radio or the charts. A four minute song with lyrics. I was on the edge, thinking where to go – and I’ve always been more schizophrenic, wanting to make all these different sorts of things and not stick with one genre.

It’s more realistic I think. That’s what people are like. They change. It’s weird to think in the past musicians would so often stick to just one style for their entire career. Nowadays almost everybody does at least a couple of very different things.

JN: Well my father was a rock musician, and he would tell me about other musicians by saying "he was playing rock" or "he was playing heavy metal". They excluded other people based on what they were playing.

Your Dad was a rock musician? Was he successful?

JN: In a way… yeah. It was never a conscious influence though, and he never pressured me to do music. I got into it more because I liked the sound aspect and the idea of synthesis and tinkering with stuff. It’s really nerdy…

Extremely nerdy…

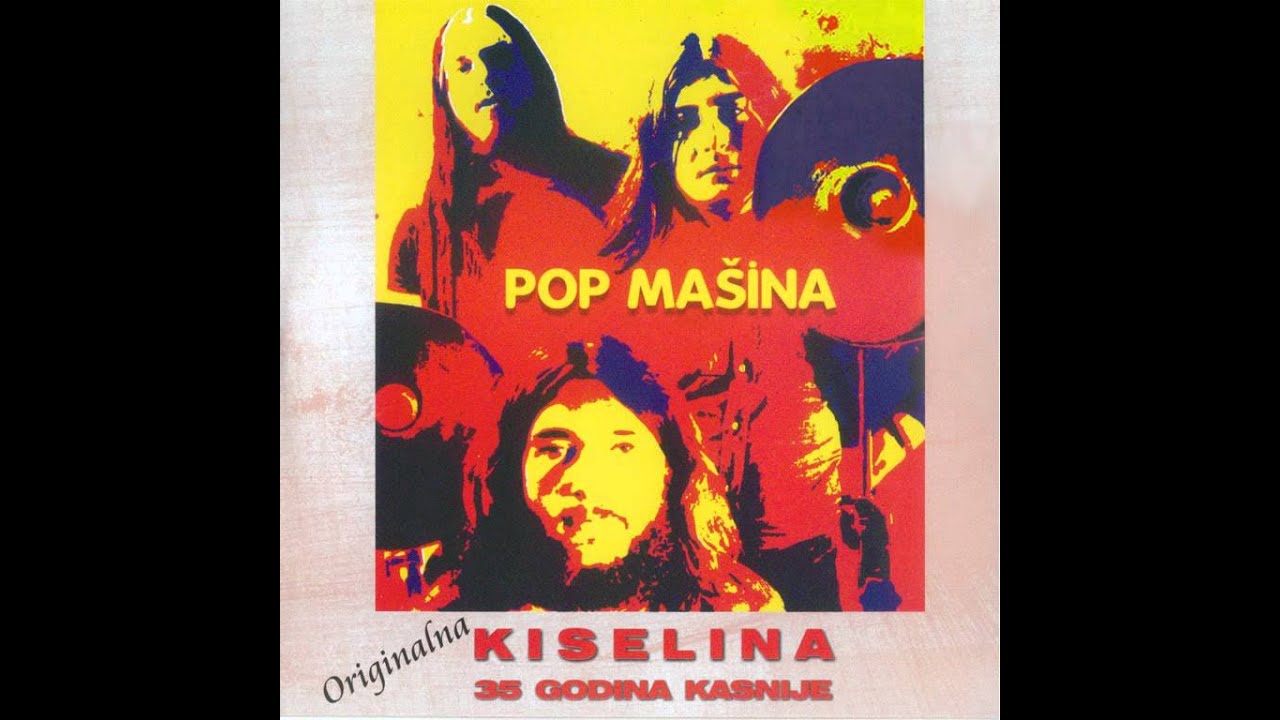

JN: Yeah, this whole thing of guys standing around comparing beards and modules! But anyway, yeah my Dad made his living as a musician up until the 80s and 90s when he moved to London for a bit and then eventually he came back again to Serbia. Up until ‘84 he made his living with music, and they were playing like… you know… stadiums. They were called Pop Mašina (which means ‘Pop Machine’), and they were kind of like a cult psych-rock band. They’re pretty well known in Serbia, and crossed over all over Yugoslavia, and recorded all their stuff in Slovenia. It was progressive rock and it was psychedelic, but it was Yugoslavia in the 1970s, so everybody was pretty conservative.

Completely unlike nowadays where nobody is conservative in Europe any more…

JN: Haha, fair point. They recorded an album about an acid trip, which I think was one of the first concept albums in Yugoslavia. It was a time when long-haired people were frowned upon – and then they recorded this album simply called ‘Acid’! [‘kiselina’] And it somehow got through the censors. They had to rearrange the tracks so it wasn’t too obvious it was an acid trip, and then it was pretty successful. I even helped my Dad remaster it for a re-release some five or ten years ago, and it’s a really good album. They were good players, and it wasn’t made in some giant studio, they scraping buy, getting an electric piano and putting it through a guitar pedal – which was like the highest tech they could get.

So what’s living and working in Belgrade been like? What’s the scene like?

JN: Well I was never really part of a scene. When you and I met before in Belgrade in 2015 [for Resonate Festival], that was about a year or two into a good period of transformation for Belgrade. The whole underground techno thing became big, and there was an opening up of things where people weren’t just listening to tech house or deep house. It was a real turning point for me back then, not long after I got this opening slot at [Belgrade venue] Drugstore. I went there and did an hour of beatless stuff, and for the first time nobody came to complain, or left. From that period to now, it opened up to a lot of people who were on the sidelines of the scene too, for younger people who never had a receptive audience. It gave me the courage to try the whole thing.