All artwork courtesy of Linder Sterling. Ballet photography by Justin Slee. Some images may be considered NSFW

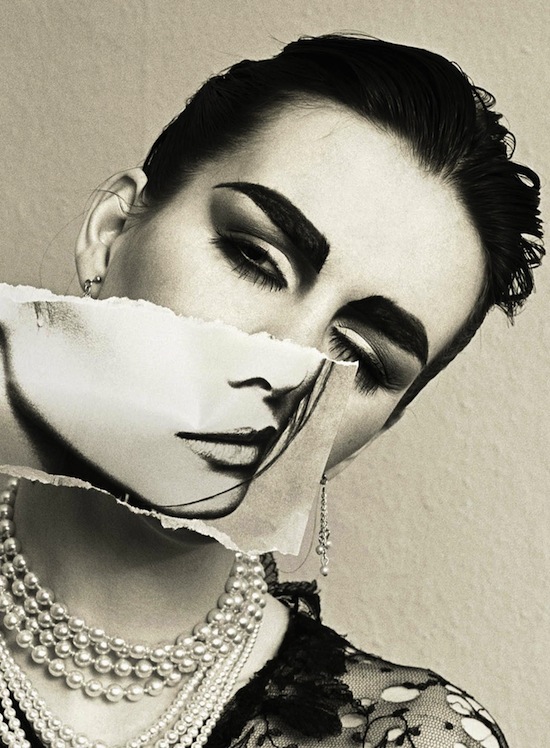

Linder Sterling is a remarkable woman. An artist able to inspire using a range of disciplines, she is probably best known for her superbly witty collage work, first launched on the British public courtesy of Buzzcocks’ ‘Orgasm Addict’ cover. Of course this is nothing like the full story.

In 1978 Linder formed the band Ludus, one of a cluster of legendary Manchester post-punk acts who were happy to explore the more esoteric or outrageous debris that the punk explosion had left in its path.

In an interview with her good friend Morrissey back in 2010, Sterling said that she saw art as “the conversion of a personal experience into a universal truth – or making a trip to the chip shop sound cosmic.”

But she is no cosy sentimentalist. Linder’s art is as sharply critical and beguilingly saucy as it ever was. And her multidisciplinary eclecticism is that of the digital age; nimbly weaving re-imaginations round the visions of the likes of Ithell Colquhoun or Barbara Hepworth into a strong, C21st feminist narrative.

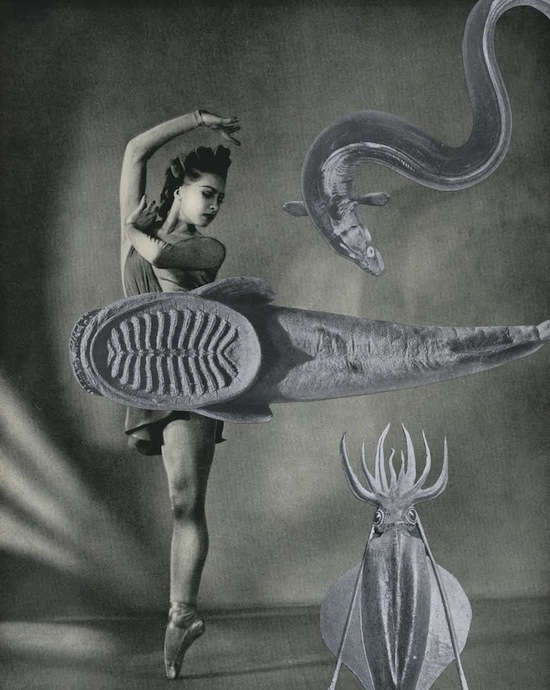

Recent forays have included ballet, film and applied work such as rug making. Viewed as a whole, this colourful and enquiring, fearless and forgiving work is – for me – yet another important testament to a peculiarly Northern English strain of the post-war British art and music school tradition that produced Brian Clarke, Harrison Birtwistle and David Hockney.

Still, an old fashioned sense of propriety still surrounds Linder. And this interview is the result of a genteel correspondence; struck up whilst she was preparing for the latest staging of her ballet, Children Of The Mantic Stain at British Art Show 8 in Southampton last November (which her son Maxwell Sterling wrote the music for) and shipping works to the Zona Maco art fair in Mexico City this February.

Currently writing an EP with Maxwell, she also oversaw the release of Nue Au Soleil (Completement) a brilliant 2 CD anthology of Ludus’s work, which (as well as the band’s complete studio work) includes Peel sessions, later and revised works, demos, and the legendary performance at the Hacienda in November 1982, when Linder bestrode the stage wearing a “meat dress”. Every Head should own it.

Without really planning to, our digital correspondence fell roughly into two “parts”, the first emails tackling how Linder created her art, the second on her brilliant band, Ludus. Now, read on…

Part The First: LINDER THE ARTIST

Work processes, inspirations and “the modern world”

Though your work has often stimulated or shocked, there’s a sense that you deal with eternal human relationships or questions. You seem to be playing a long game. Which is very giving, comforting almost.

Linder Sterling: In 1981, I sang, “I’m the one that’s asking questions, I’m the one who will not play your game” and I’m still picky over the short and longterm games that I play. The political challenges that we met in 1977 could turn out to be very similar to some of the challenges that we’ll have to meet in 2017, there’s a strong sense of déjà vu around for those of us old enough to remember.

But your work doesn’t feel as if it’s concerned with commenting on the current zeitgeist. You use lots of old, or “eternal” images, like the naked body, and common, or shared visual memories…

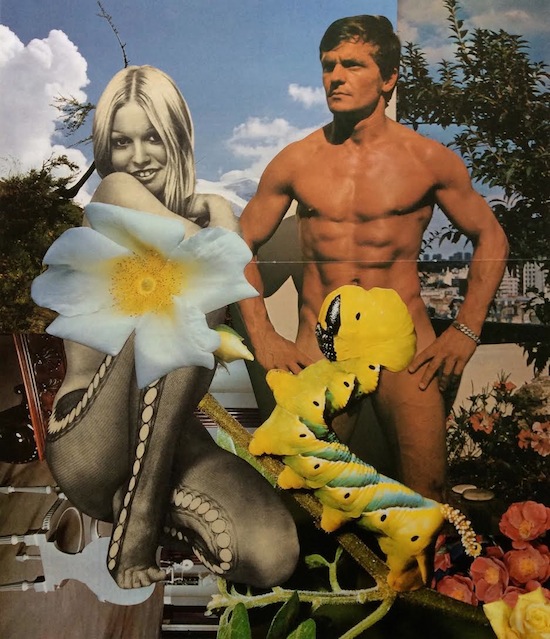

LS: I play with time all the time, it’s an endless source of fascination. Sometimes I play with images from the present moment, culling from contemporary hardcore pornography, cup cake magazines, large scale calendars showing idyllic English gardens for every month of the year, car magazines, fashion magazines… whatever’s to hand. I can be all-encompassing in my use of imagery when I get going. At other times, I combine cutouts from different eras so that time itself is hard to pinpoint amidst the shifting halftone dots from the developments in each era’s technology. People often can’t work out when I made a particular work. Others ask to see the originals, presuming that they’re seeing a print out, rather than a conflation of glued cutouts. When I made the first photomontages in 1976, many presumed that I was male, working with the pornographic image was somehow seen as a non-female domain.

From what I have read of your work processes it all sounds like some Cold War spy operation. I mean, all that extensive image and info collation and cataloging, the searching out of the arcane, marginal or perverse… And your discovery, and use of magazines such as Transsexual Horse Lovers… Somehow you work undercover, along secret lines… ferreting out info, patience, a passivity in looking for things to fire your imagination. You told me you had to go to Accrington to find a place (on Accy market) that sold the Liberty bodice.

LS: Yes, there is an element of the undercover when sourcing materials with which to work. I use various pseudonyms for the different collectors that I buy material from. I happened to let slip recently that I wanted to buy a book to cut up and the collector wouldn’t sell it to me because he said that that would be killing the book. He’s got a point; the books are “dead” as objects once I’ve finished with them, but their imagery has a new and vital life in a different cultural arena. The book in question was Hutchinson’s Animals Of All Countries from 1924 and I soon found a copy elsewhere.

The photomontages that I made from its pages will be seen by thousands of people in Mexico City in March; so for me, it justifies the kill. I displace images all the time. And to paraphrase the late John Berger, it’s a new way of seeing all that’s familiar.

You once said, that that for you and your friends, punk was “all about getting ready, never arriving”. Are these sorts of selective processes achievable in an age of instant display?

LS: Yes, of course! Jon Savage and I published The Secret Public fanzine in 1978, it did what it said on the can. Decades later, no one forces eighteen year olds to take highly stylised selfies in their bedrooms, or foodies to take overhead shots of every breakfast, it’s all voluntary.

Also, in the late 1970s, the clubs in Manchester rarely delivered on their promise, and I’d end up dancing to the Philadelphia Sound at The Continental, rather than standing still at the Electric Circus. I was much happier whenever I could dance.

“Books, shops, and boredom…” Are these the evergreen ingredients for your art? Or is the world of imagining black and white reproductions of pictures you’ve never seen in colour down your local library long gone now? In fact, could you imagine starting out now?

LS: I long for boredom sometimes, it’s all too rare a sensation now. Maybe boredom isn’t the exact quality that I crave, maybe it’s a sense of absorbent stillness, rather like the paper cut-outs that I glue together? Hildegard of Bingen said that virtue was moist and sin was dry. Maybe we all, at heart, are waiting for the right cosmic glue, and the right principles to adhere to? If I started out now, I’d probably study medicine and get a real job.

Is there ever any urge to just sack it all off and use Illustrator or Photoshop and start creating digital images?

LS: I sometimes work digitally but not often. If you know where to look, black and white and colour negatives from different eras of photography are becoming more and more available. I presume it’s because the photographers’ estates are now up for grabs. In the past, I’ve worked with medium format negatives and enlarged them digitally, so that the human figure in the final photomontages are larger than life.

It’s difficult to successfully reach the same scale with images taken from print media. I find the enlarged halftone dot too distracting. Photoshop can make everything too easy, everything is possible in the hands of a good retoucher, look at any authorised photo of a celebrity to get my point. I still prefer the creative challenge of working with the found paper image in the main, I like the sensuality of the cut and the messiness of the glue. Often, the application of glue can release all sorts of smells that have been absorbed by the paper over the decades, tobacco is the strongest scent, sometimes there’s a faint whiff of perfume or fried eggs. You don’t get that olfactory rush with Photoshop and I miss it.

Linder and Feminism

How would you define “the personal as political”, nowadays? For an original Spare Rib and Female Eunuch – inspired feminist, I’m going to stick my neck out and say that the sort of images you are known for are very different to what current consensus would see as feminist. They often feel traditional: kitchens, roses, ballet, cakes, end-of-the-pier sauciness… “Things getting groovy in the kitchen.” Why this subject matter?

LS: The phrase “the personal is political” was originally the title of an essay written by Carol Hanisch in 1969 and I read it in 1970, when I was sixteen years of age and I pondered her every word. In her essay, Hanisch argued that women aren’t messed up, they’re messed over and it’s still true decades later. 2017 will be a litmus paper test of just how messed over we could all potentially be with Trump as president of the USA, never mind the delights of Brexit yet to unfold.

I often use an archaic palette of imagery that reflects the cultural messing over process, it’s a useful way to trace some of the etymology of the images that we see around us now. When I was a child, I was always given a ballet annual for Christmas, I was fascinated by the sartorial democracy shown on each page. For instance; both sexes wore tights and heavy makeup, and seemed to lead perpetually enchanted lives. Meanwhile, I lived on a council estate in Liverpool and in my heart I knew that I’d never make it to a barre. Other girls that I knew longed for ponies, but that was never going to happen either. My childhood and adolescence was all to do with unrequited desire.

The success of lifestyle TV proves that the British still get very excited by their gardens, their rose beds, the design of their kitchens and the size of their muffins therein. I’ve never seen The Great British Bake Off but the name smacks of a cosy notion of tradition and carbohydrate-laden competition. Mary Berry could be said to have more cultural clout now than she did in 1977. So, a lot of the imagery that I used to make point in the late Seventies makes even more of a statement now; because now women are expected to have careers, families and be able to bake a perfect Victoria sponge in the midst of it all. Something has to give somewhere.

Though your work is very giving, it doesn’t feel academic or out to impress, in the sense (say) John Heartfield’s or Richard Hamilton’s photo-montage work does. Your recent naughty postcard work is surreal. The images make me think, ‘what the bloody heck is a rose head doing there?’ It’s like a no-nonsense attack on a striptease.

LS: The rose cartoon series were made in homage to Max Ernst’s ‘Une Semaine De Bonté’ from 1933. Decades later, in 2004, I was suddenly intrigued by the idea of montaging cartoons together rather than photographs. I was in the midst of making a series of photomontages from 1960s copies of Playboy and The Rose Annual. I became fascinated by the cartoons in the former and the adverts for new hybrids in the latter.

At the opposite extreme of the 2004 postcard series, are the 2-metre-high light boxes that I started to make in 2011. The sheer scale yields a visual clout, as if I’ve stolen a JCDecaux display from an airport and rearranged its contents.

Linder Over Lancashire…

The journalist Charles Nevin wrote a whimsical coffee table book called Lancashire, Where Women Die Of Love. That quote is – apparently – from Balzac… Your images struck me as “feeling” Lancastrian. Earthy, sharp (excuse the pun) and ever so slightly gluttonous. Is this observation fair? Do you consider your art "Northern" or North Western?"

LS: A lot of the works that I make are incredibly gluttonous!

There are recent photomontages made from contemporary pornography, fashion and food magazines that each give The Great British Bake Off a whole new level of meaning. I like to see how far I can ramp up desire within one image until it becomes grotesquely comic. A photograph of a chocolate eclair glued over an erect penis is very Carry On, it’s also a part of my visual esperanto. Sixteen year olds in Tokyo and Dallas get the joke without ever having set eyes on Kenneth Williams.

I never think of my work as Northern or even British. The French were the first to host a major retrospective of my work in 2013 at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, but there’s never been a similar invitation from a British institution. The stork obviously made a mistake when I was born and delivered me to an Anglo-Irish family in Liverpool, rather than to an haute bourgeoisie family in Normandy.

Part the Second: LINDER AND LUDUS AND MANTIC STAINS

Ludus seem – on listening back – to be tremendously playful, colourful and bright. Your band also sounds as sharp as your collage knives too.

LS: When I exchanged the scalpel for the microphone in 1978, I’d never sung a note beyond the confines of the school choir. I was curious to know if I could make a mark with my larynx in much the same way that I had with the found image and a Pritt stick. According to the French philosopher Roger Caillois, who classified the four patterns of play in 1958, “ludus” means “the taste for gratuitous difficulty”. So, off we went, making life difficult for ourselves at every turn, but pleasurably so.

The decisions, and attitudes struck in the music are very noticeable, strong. It’s bright, and definite pop music. At odds with the image of the dour North West of the time. I can only think of Jayne Casey – or Slits – having a similar sense of bright colour and fun.

LS: We dipped our toes in and out of pop but I knew in my heart that I’d never see Pan’s People dancing to ‘My Cherry Is In Sherry’ on Top Of The Pops. On the LDDC compilation, you can hear ‘Vagina Gratitude’, which we’d recorded for a Peel Session in 1982, the song being a retort to Freud’s theory of penis envy. On air, John Peel said that he was blushing as he read the title out loud, it didn’t take much to make men blush then.

I get a strong feeling, too, that your music can be seen as a herald for things to come. Or a very clear clarion call for something new that’s about. One track is very much like an early Orange Juice track for example! I’m not accusing anyone of nabbing things, but it always strikes me that the commonality of music in post-punk & punk is remarkable, given that no-one really seemed to speak to each other outside of small closed scenes. Is that fair comment?

LS: Considering that post punk was pre-internet, “newness” was often transmitted eerily quickly. I remember when Ian Devine first played live with Ludus at the “Stuff the Superstars Special” in Manchester in 1979. Ian had trained as a jazz guitarist since he was young, and he always held his guitar relatively high in traditional jazz fashion. In the weeks that followed, other guitarists started to inch their guitars higher and higher too, so that eventually Ian lowered his. At the “Stuff the Superstars Special", we played one song which lasted 17 minutes and probably had as many tempo changes. That never caught on with others though.

What do you feel about Ludus now? Do you want to become "part of the canon”?

LS: I feel very affectionate towards my younger self and all of my fellow collaborators. I think that we were very brave at times. We perpetually took ourselves out of our comfort zones and tirelessly explored endless possibilities, to create music for the times that we lived in. There was an exhibition last year at Franklin Street Works gallery in Stamford, Connecticut and it took its title – Danger Came Smiling – from the final Ludus album. It brought me enormous pleasure to know that the curator, Maria Buszek, had gathered together a new generation of artists who had been influenced by an album on which I use my larynx in the main to cough, scream, cry and laugh. It gives one hope.

Let’s talk about your ballet, Children Of The Mantic Stain. I wonder, do you see it as a physical work first, or a visual one? The dancers seem so close together, all the time: there’s a sense of continuous interweaving with that big, curly, gold-backed rug (sorry I can’t think of another description).

LS: The ballet works on many different levels all at the same time, as if animating every photomontage that I’d ever made so that the eye never knows where to rest. The ballet was commissioned for the British Art Show 8 in 2014 and it incorporates a rug that I’d designed, also for BAS8, with Dovecot Studios in Edinburgh. The rug was displayed in the galleries of the BAS8 in each host city but it was removed from public display each time that the ballet happened, it became the “eighth dancer”. I wanted to liberate the rug from the traditional horizontal plane that we position it in in the home, I also wanted to see an inanimate object choreographed and a rug seemed as if it had the most possibilities. The rug is backed with gold lamé as a nod to Elvis Presley’s $10,000 gold lamé suit made by Nudie Cohn in 1956, normally rugs are backed with brown jute but I wanted the rug to be equally glamorous whichever way you looked at it.

Maybe I should ask what is behind the ballet?

LS: The Children Of The Mantic Stain ballet emerged from research into the life of the British Surrealist artist and writer Ithell Colquhoun. I was artist in residence at Tate St Ives for six months in 2014 and I spent most of that time in the newly discovered archives of the Penwith Gallery that had been founded by Barbara Hepworth, Bernard Leach and Ben Nicholson in 1949. However, the more that I researched the great and the good, the more intrigued I became by those who were excluded – or chose to exclude themselves – from that circle. Ithell Colquhoun not only exiled herself from the St Ives Modernists but from most of Cornwall. She was incredibly self-contained and often more at home in the spirit world than with the living. The ballet imagines an encounter between Colquhoun and Hepworth at the Penwith Arts Ball in 1956 but it also works on the traditional boy meets girl, plus boy meets boy, narratives too. The same could happen in Wigan any night of the week, two boys take too many drugs one night and watch the carpet come alive, just as their friends call round to take them out. Classic.

What is a Mantic Stain? It sounds like an ailment my grandmother would have had.

LS: Ithell Colquhoun wrote her ‘Children Of The Mantic Stain’ essay in 1952. The title sounds very Marvel comics, but Colquhoun’s isn’t about a mutant gang in Ohio. Instead, her essay details the full range of techniques of automatism within the visual arts. “Mantic” is of Greek derivation, it means “oracular, divinatory”, it also points towards a state of divine possession. Collage is one of the techniques described in ‘Children Of The Mantic Stain’ but I was far more interested in Colquhoun’s experiments with enamel paints, I’ve consistently experimented with the latter over the last two years.

And from what I’ve heard, the music (scored by your son) sounds so brooding, almost the opposite of what is being played out by the dancers. It makes everything very tense. Were you aware of that tension beforehand?

LS: I never make life particular easy for my fellow collaborators, and my son, Maxwell Sterling, is no exception to that rule. I always want the best from everyone that I work with, and for The Children Of The Mantic Stain ballet, the list of collaborators was long. And we all kept the bar as high as we could throughout. For the score, the first challenge was to work out how the sound could, at times, have the quality of a mantic stain and create auditory hallucinations, or become oracular of what was yet to happen within the narrative. Max composes music for films and we decided to approach the ballet as cinema. Sometimes Max’s score mirrors the choreography and at other times it pushes against it. I know what you mean about the brooding quality.

Maxwell’s score was choreographed by Kenneth Tindall with dancers from Northern Ballet, the dancers were dressed by the fashion designer Christopher Shannon and, as I said earlier, the “mantic rug” was created at Dovecot Studios in Edinburgh.

There’s a clearly definable continuum between Ludus at its most experimental and the work that I make now. Destination Moon. You must not look at her! was a five hour performance created for the inaugural Art Night hosted by the ICA in London last year.

I inch closer and closer to becoming Busby Berkeley, letting others sing and dance on my behalf, fleshing out the many montages that await in my psyche.

Nue Au Soleil (Completement) is out now on Les Disques Du Crepuscule