Cover artwork for Tape Loops by c.reider

"One of the tracks – I’m fairly sure I’ve been set up, but I don’t know who by. They sent me a track from a series called ‘Benson & Hedges’, which is recordings of George Benson and hedge trimmers." Richard Sanderson pauses over his pint of best, pondering for a moment whether this is a wicked joke at his own expense or a genuinely inspired art project. "Now, I took this in good faith," he continues. "Apparently they had a whole series of recordings of George Benson records overdubbed with people trimming hedges. Now, you know, I’d probably put a whole album of that out."

I’m sitting in a pub off Borough Market with Sanderson, the founder of Linear Obsessional Recordings, and we’re talking about the open-access compilations his label started doing three years ago. Specifically, we’ve been going through some of the more unusual submissions to the 2015 album Open The Window, which finally ended up as a mammoth 85-track, 170-minute monster, available to download for free from the Linear Obsessional website and Bandcamp.

Sanderson promised to accept anything people sent in for inclusion, so long as they adhered to two ironclad rules: the track must be exactly two minutes long and it must be recorded, using a microphone, with the window open. "Some of the stuff I got sent!" Sanderson exclaims. I mean there’s one from a spaceport in Russia. There’s one somewhere off the Volga, one from Uganda. So it really was a nice global thing.

"I love the fact that some people just opened the window and sang a folk tune," he continues. "Others just went for completely pure, ‘Right, I’m just going to open the window now and get two minutes of whatever’s happening.’ There’s one that sounds like absolutely nothing. Just a very faint sort of atmosphere. Nothing else. Not even a car drives past. And I like that!"

It’s difficult to trace the origins of Linear Obsessional Recordings. "I used the name Linear Obsessional for a couple of releases of my own," Sanderson recalls. "I think there’s one from 2005, which was a little EP of songs. Mark Spybey sent me an old compilation tape I’d done of my own music for him, and this was probably about 25 years ago. And on that I’d put ‘music copyright Linear Obsessional’. So I don’t know, really, how long I’ve been using it."

But the label as it exists now began in 2012 with a collaboration between Sanderson and Glaswegian sound artist Liam Stefani, aka Skitter. The name, Sanderson explains, "is something along the lines of a one-track mind." He points to recent releases like this this by Phil Maguire, a popping, whirring, stuttering thing created entirely on a Raspberry Pi computer, as characteristic. "That, to me, is very much a Linear Obsessional thing. It’s just got an idea and he’s run with it. And also because I’m quite obsessive about stuff as well."

But the Linear Obsessional output is neither all abstruse and electronic, nor really all anything. There are pop songs by The Original Beekeepers, swirling outer-space blues jams by Mike Cooper, poems by Jude Cowan Montague and free improv by the likes of Steve Beresford and Anna Homler. "Rule of thumb," Sanderson says, "is anything I like."

Inspired by net labels like Test Tube and Impulsive Habitat, all releases on Linear Obsessional are available to freely download, with physical copies available in runs typically limited to just 50 CDs.

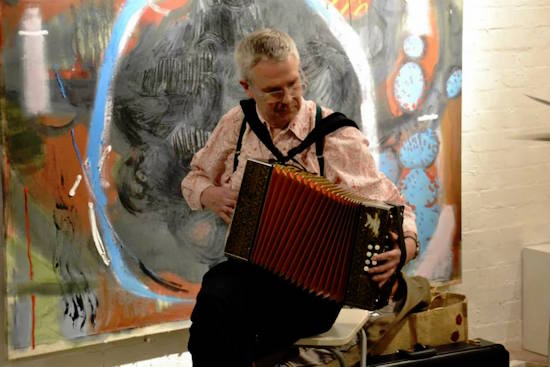

Richard Sanderson

"Richard is a thinker and project-orientated," Kev Hopper tells me when I asked him about the label. The Stump and Prescott bassist’s solo album, Tonka Beano, was released by Linear Obsessional in 2013. A thrilling dialogue amongst multiple virtual machines like a pachinko parlour slowly developing consciousness, it remains one of Sanderson’s favourites releases on the label.

"He had talked about a net label a long time before he put it together," Hopper recalls. "I laughed when he told me it would be called ‘Linear Obsessional’ because he loves science-lab words and his songs are often called ‘Parallax’ or something similar."

Hopper and Sanderson first met at a Stump gig in the 1980s. "I don’t remember much about it," admits Hopper. "He says I bought him a pint so I must have made a good impression on him. Later, around 1996, I saw him play a gig in Stockwell when he was playing with amplified toys, got chatting with him and talked about getting together to play." For several years, Sanderson and Hopper, together with Phil Durrant, played together in the electronic trio Ticklish. "Kev and Phil were both using Reaktor on laptops," Sanderson says, "and I was sort of faffing around with all these samplers that you press buttons on."

"They got completely obsessed with it," he continues. "Kev, especially, just started making these incredibly elaborate machines. And then Kev being Kev just said, well, I’ve had enough, and just went off and started on some other musical obsession for a while. It might have been the musical saw. He’d basically made all these machines and left them on his laptop. So I said, well, how about, why don’t you just set them running and I’ll put it out? He came back with what I think is a masterpiece of electronic music. It has only just sold out as a physical copy. So it did well."

Sanderson’s entrée into the world of experimental music arrived at a young age. "My father was a lecturer in computer mathematics in the early ’70s," he recalls, "and he used to do a lecture which included some aspects of electronic and computer music – including things like [John] Cage’s HPSCHD. Some of the longhairs there were enthused by this and lent my dad some albums, most of which left my dad pretty non-plussed, to be honest. But I, as a 12-year-old, was fascinated – the ones I really remember were the amazing Avantgarde set on Deutsche Grammophon and the Faust Tapes, which I taped and played all the time."

A few years later, in 1974 at the age of 12, he figured he could give this a go himself. "I can’t really remember how it happened," Sanderson admits. "How we went from being child prog enthusiasts. Then at some point we went: why don’t we make music? Even though we had no instruments, no skill whatsoever. But we did it."

Solaris, Sanderson’s first band, featured his cousin, Mark Sanderson, playing acoustic guitar with a battery as a slide and best friend Mark Spybey (later of Zoviet France) playing a single Boys’ Brigade drum. They played what Sanderson recalls as "a sort of thrashing free-jazz stuff" in mid-’70s Teesside, inspired by Tangerine Dream records and a group outing to a Kraftwerk gig in Middlesbrough. In 2010 they reformed for a series of summer recording sessions at Spybey’s place in Northumberland. The results, released on Linear Obsessional in 2016, sound like nothing on earth.

In the 1980s, having made the move down to London, Sanderson wound up in the free-improv scene around the London Musicians Collective, later organising the Club Room concert series and presenting a show on Resonance FM. "When I first started going to improv gigs, it was all bearded blokes in their fifties," he recalls. "There really were no women at all. You were lucky if you got one woman performer. There were never any in the audience."

There was something generally quite occult about experimental music at the time, a hermetically sealed world seemingly open only to initiates. "It was a matter of sending stamped addressed envelopes off to nutty little labels in Hackney or somewhere," Sanderson recalls, "and you’d get this catalogue back and look at it and go, hmm, that sounds interesting…"

All that has changed now. "Now it’s incredibly diverse," Sanderson says. "I think the improvised music scene in London has never been so healthy." He remains a regular performer, as well as helping to organise the Convivium club with Adam Bohman and Tim Yates, plus Linear Obsessional’s very own live series at the ArtsCafe in Manor Park.

"At the moment," Sanderson says to me finally, "I’m kind of toddling along." He’s recently released an album of his own solo melodeon improvisations, with plans for several other records in the pipeline – including, perhaps, a return to his roots in the northeast. "I’m keen at some point to do a compilation of experimental music from Teesside," he tells me. "I was thinking of doing one from 1975 to about 1985. Just because Teesside is an area that not many people know anything about, but it’s this incredible, industrial place. And I think it has had an effect on some people."

In the meantime, there will always be a little bit of experimental Teesside – and, indeed, a whole world of strange sounds and interesting ideas – in South London, thanks to the continuing efforts of Richard Sanderson and Linear Obsessional Recordings. "It’s about taking things in a line," Sanderson says. No matter in what direction that line tacks, it’s sure to be worth following.

A Thousand Concreted Perils by Richard Sanderson is out now on Linear Obsessional