This year’s Atonal festival feels like it has reached a tipping point, though what it has left behind or what it is yet to reach is not clear. It seems that it might be buckling under the weight of its own deservedly glowing reputation as an event – earned for what its founder, Dimitri Hegemann, described as ‘serious, existential music’ – a reputation which has grown stratospherically since its re-launch in 2013, and one which may now require a little probing as to what its future will sound like. It is more than likely that this present problem is one that is shared by Berlin’s music scene as a whole, and indeed other pockets across the globe, but Atonal has always been about Berlin: a microcosm of the cultural and historical developments of the city. It’s natural, then, that the “symptoms” of this apparent malaise would be more keenly felt in this condensed environment. Saturation, you might call it.

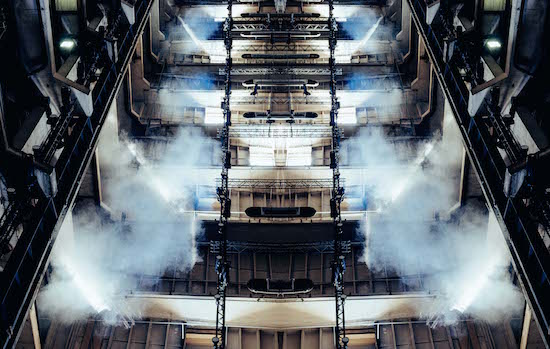

Vernacular wisdom has it that identifying a problem comes partway to solving it, but in the case of Atonal that doesn’t seem to hold true, and a glib sigh of “It just feels different” cannot get us any closer either. Another confounding factor appears to be that no one can be held accountable, certainly not the organisers, who programmed a mouth-watering roster of artists, even further left-of-centre than in previous years, in a venue that is second to none. Enough ink has been spilled extolling the virtues of the Kraftwerk complex, but it should be added that its peculiar magic grows no weaker with each visit, especially when peppered with art installations, food trucks, and expanded to include the festival’s majestic main stage on the first floor.

One accusation that is levelled at the organisers is that this year’s significant increase in audience capacity is not properly accommodated. Seeing an hour-long queue for OHM on Wednesday night lurches your stomach and grows to all-pervasive nausea by Thursday: what were to be real highlights of the festival – DJ Sotofett, Andrea Parker, Nuel, and Skee Mask – would subsequently be missed. But what is the solution? To restrict attendance would be to go against one of central ethos of the festival, which is to bring experimental electronic music to the audience that wants to hear it, and given Atonal’s afore-mentioned reputation, a return to the purity of origins is now unthinkable. Besides, the fact that this music has this substantial an audience is surely worth preserving, and given the barbarism, in the truest sense of the word, that has led to the closure of fabric – a beacon of London’s music scene – every space and every event that is allowed to continue catering for this branch of the underground should be nourished and supported most vehemently.

Perhaps having Tresor and Globus open on all five nights of the festival in the future would dissipate the traffic, although the fact that so many people want to flock to and seek solace in OHM, which offers more palatable and DJ-friendly programming than the other venues, suggests that there may be a disjuncture between what people think they want from Atonal, and what they actually want when they are here. Understandably, hearing a Stanislav Tolkachev record in Tresor at 1am on a Wednesday night is not for the faint of heart, and an alternative to the carnage it inspires would be welcomed with open arms.

Rashad Becker and Moritz von Oswald deliver what is unquestionably the most timely, timeless, and interesting set of the festival. Von Oswald’s piano sounds like a cross between Kurtág and the Ligeti heard in the soundtrack to Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut, with some decidedly fruity harmonies thrown in for good measure. Becker’s aesthetic meanwhile dominates the electronics, which are presented as both calculatedly sober and maniacal, full of pathos. This is new music – a music which breaks through the screens of representation without nullifying itself through abstraction; a perfect harmony of form and content; a music which goes beyond language, meaning and symbolism and focuses on the possibilities inherent in sound alone. Performing on Friday night, ∑ (aka Summe) seems to have similar aims – his music is a meditative, metal-tinged study of sound synthesis, a series of études almost, and for the first time this year, and quite fleetingly, it feels like Atonal again.

In terms of audio-visual performances, The History of Darkness by Recent Arts and Telluric Lines by Jonas Kopp and Rainer Kohlberger on Wednesday and Friday nights respectively mesmerise and transfix the audience. It is quite an achievement for neither element to feel auxiliary, and, regrettably, at frequent points during the festival they do, but these two acts accomplish the feeling of a total artwork – completely immersive and yet not prescriptive enough to proscribe independent thought and interpretation.

Beauty is in no short supply either, despite Atonal having a reputation for a kind of aesthetic austerity. Fundament, by the duo Upper Glossa, is reminiscent of Andy Warhol’s Sleep – static and familiar in a way that alienates – with a single retrofuturist drone as pulse and sumptuous guitars. Imaginary Softwoods and Alessandro Cortini’s AVANTI present perfect ambient music, but AVANTI especially, through its intensely personal nostalgia, raises some uncomfortable questions about listening environments, or more precisely whether music that is usually enjoyed in a deep solitude can still resonate on an individual level when it is made to be heard communally.

Jealous God’s Optimistic Decay showcase on Friday is also a highlight, mostly because letting a label curate seven hours of music provides a sense of structure, stylistic cohesion, and a pre-meditated narrative arc. Unlike its kindred festivals, CTM and Unsound, Atonal doesn’t base its programming around a theme, so Optimistic Decay appears as refreshingly sure-footed, nestled as it is between five days of the most eclectic, and often contradictory, musical vignettes. One true stand-out in terms of the more danceable sets was Ectomorph – a duo who seemed to completely dismantle the type of mania that Tresor usually inspires, and present low-slung, free-floating tempi, skittering drums and the most lyrical, expressive, and groove-laden basslines you will ever hear.

All the acts mentioned above were exceptional because they broke the mould, and introduced much-needed new blood into a musical gene-pool that – it is fair to say – has become somewhat stagnant. Atonal is meant to be about making it new, and it is hoped that next year it will resume this task. This year, unfortunately, most of the sets not mentioned do not create the new, but rather deflect and let the audience revel in what is a façade of novelty and seriousness.

The German language has a nuanced distinction between entertainment music, Unterhaltungsmusik, and art – ernste musik. The former can be serious or moving in affect, but like Nietzsche’s Apollo it seeks only to appease. The latter, on the other hand, is earnest creation, earnest destruction, and seriousness of intent and a classification rightfully earned by Berghain earlier this month. This year at Atonal, Apollo reigns, but there is promise that Dionysus might return for an earth-shattering 2017.