"A jack-in-the-box, a Fabergé gem, a clockwork toy, a chess problem, an infernal machine, a trap to catch viewers, a cat-and-mouse game…"

This isn’t the tagline of Frank Ocean’s new album Blond(e), but Mary McCarthy’s far-sighted 1962 review of Nabokov, which effortlessly describes another innovative masterpiece that similarly refuses to be pigeonholed. Just as the genre-bending Pale Fire isn’t simply a "novel", Ocean’s latest output hardly deserves to be called an "album" alone – more like a fully-fledged pop culture event, following other much-hyped recent releases from Beyoncé, Kanye West and Rihanna, to name a few.

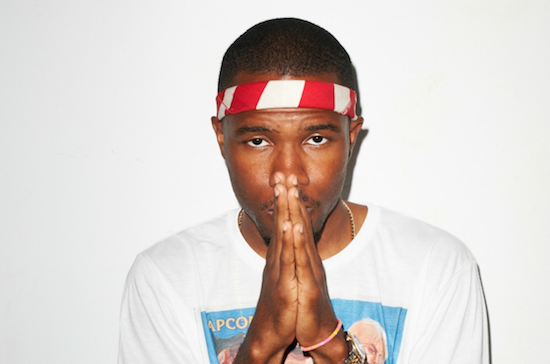

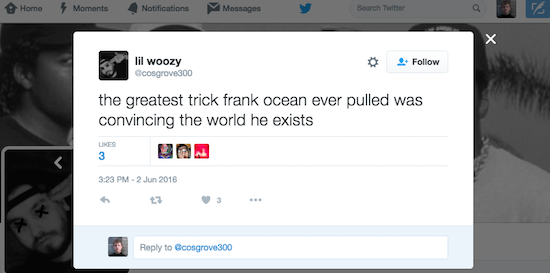

But unlike them, Frank Ocean – the man and the myth – invites a whole new level of scrutiny. Ever since the widely circulated 2012 open letter that revealed his painful, unrequited love for another man, the most reluctant mainstream pop star of our time has shrouded his activities in almost total obscurity. Traces occasionally surfaced here and there: a smattering of guest vocal appearances (such as on The Life of Pablo), whispers of secret listening parties hosted in New York, a Calvin Klein ad that looks like it could have been lifted straight from his cryptic Tumblr blog.

All the while, diehard fans congregating on Twitter and Reddit descended on any morsels of speculation they could find, including hints from his former producer Malay and since-deleted Instagram posts from collaborators Lil B and Nabil. By following these vanishing internet paper trails, they were only recreating what everyone had tried to do with the notable male pronouns in the lyrics of his previous release, channel ORANGE – only this time, in Ocean’s real life.

Nonetheless, in both life and art, Frank is everywhere and nowhere, an absent presence who commands yet shuns the media hyper-saturation that the music industry machine demands of its stars. He’s the artist who writes himself and his queerness in and out of his work, enticing the listener down seductive musical rabbit-holes only to deny them any concrete explanations. The confessional queer speaker from channel ORANGE who plaintively cries "I could never make him love me" on ‘Bad Religion’ seems unusually absent on Blond(e). Apart from ‘Good Guy’ which tersely sketches out a failed date at a "gay bar", there are no explicit references to a specifically male lover elsewhere in the album, although it has plenty of passing nods to sex and erotic desire.

To detangle these shadowy half-clues on Frank Ocean’s sexuality, then, we would need to look further afield. In this respect, Ocean may have provided us with the biggest clue of all via his decision to drop an unexpected visual album without any context, Endless, as well as a magazine, Boys Don’t Cry alongside Blond(e). Working across a variety of media, Ocean lets his strong aesthetic sensibility reveal yet another layer of coded signs for us to analyse endlessly, if you’ll excuse the pun. Added to the ambiguous duality of the album’s title Blond – or Blonde, as it’s shown on Apple Music – Ocean is practically demanding that we mustn’t fall into the trap of taking his music entirely at face value, of pinning a neat, singular resolution on the enigmatic collage of impressions and fragments that’s been presented to us. Instead of spoonfeeding us an explicit, straightforward answer, his art prefers to swerve along the queer, digressive path, forever eluding his audience in ways that are as fascinating as they are maddening.

More than anyone else in mainstream pop right now, it seems, Frank Ocean knows the complicated, double-sided thrill of being chased. Ironically, when he uses this queerest method of all – one that’s familiar to anyone who has ever been in the closet themselves – we can’t help but indulge in the pleasure of the musical and visual games that he carefully orchestrates as a result. He slyly drops a slew of queer and camp references in the video for lead single ‘Nikes’, as well as queering pop culture’s touchstones: the iconic shot from American Beauty is uncannily reimagined as androgynous black bodies sprawled on a pile of money; the camera’s gaze repeatedly lingers on Frank’s muscular, honed torso for a moment too long; the pioneering spirit of gay filmmaker Derek Jarman lives on in the strippers in angel wings, and the haze of glitter that clings onto male and female bodies alike. Even the car, that classic symbol of fearless masculine machismo, is morphed into a cocoon of escape where Frank, sitting alone with tears streaming down his face, embraces his isolation and vulnerability.

These double-take inducing moments – where the camera shows us one conventional form of feminine beauty that’s suddenly displaced onto a beautiful, androgynous man – even carry over to the songwriting on Blond(e) and Endless. His consistent refusal to use pronouns of any gender when describing universal tales of fleeting encounters, almost-relationships and suppressed heartbreak makes the queerness of his music even more powerful, especially when coupled with more obvious visual references from the ‘Nikes’ video, and the sensual photo spreads of lithe young men in Boys Don’t Cry.

This tantalising possibility of ambiguous, interchangeable male and female love objects invites us to imagine these shadowy half-lovers however we wish – even if they turn out to be a hopeless fantasy of the lovelorn speaker. "What could I do to know you better than I do now?" repeats the outro to ‘Alabama’, while he promises that "I’ll be the boyfriend in your wet dreams tonight" on album highlight ‘Self Control’. For every desperate plea of love that’s proffered, there is a hasty retraction, an offhand shrug: "Been living in an idea/An idea from another man’s mind", he reveals on ‘Seigfried’. ‘Ivy’ contains another revelation disguised in the banal: "I broke your heart last week/You’ll probably feel better by the weekend". Even a line that leaves nothing to the imagination, such as "All this drillin’ got the dick feelin’ like a power tool" from ‘Comme Des Garçons’, buries a double entendre that could refer to him or a male lover (the "power tool").

A master of endless contradictions, Frank Ocean wrong-foots the listener time and time again, forcing them to re-examine their presumptions of what love songs should (or shouldn’t) be. His art not only bleeds from one genre and medium to another, but is also fluid in its portrayals of gender and sexuality. "Dynamic" is the only word he used to describe his sexuality in a 2012 GQ interview, and this prescient attitude to self-definition is almost fully accepted as gospel by the Tumblr generation in 2016.

His distaste for neat, fixed identity categories – "You can’t feel a box. You can’t feel a label." – seems to have paved the way for many queer and gender non-conforming young black creatives in the public eye right now: think Angel Haze, Young Thug, Jaden Smith and Amandla Stenberg, for instance. Beyond these inspiring figures, even straight-identifying male R&B artists such as Kanye West, Blood Orange and Chance the Rapper are daring to show new forms of masculinity in their avant-garde, emotionally indulgent recent works.

So while Frank Ocean is certainly not making some kind of torch-bearing LGBT liberation statement in his latest releases, they are no less powerful and visionary for aligning his queerness – even if it is highly coded and enigmatic – with the experimental, boundary-pushing mood that’s taken hold of so much mainstream R&B right now. This subtly hinted version of queerness is almost like a modern variation on the flamboyant displays of queer sexuality from other androgynous male icons of music history, including Prince (who Frank eulogised in a moving <a href="http://frankocean.tumblr.com/post/143175497681/im-not-even-gonna-say-rest-in-peace-because-its target="out">Tumblr statement) and David Bowie (who features prominently in Boys Don’t Cry).

Ocean’s music doesn’t exist purely in a queer echo-chamber, though. He combines these influences with numerous cherrypicked name-drops and quotes from an eclectic variety of "straight" sources such as The Beatles, The Fugees, Trayvon Martin and even Elliot Smith. But the way he deftly interweaves queer and straight, male and female, mainstream and counterculture, leaving these binaries much less clear than how he found them, is an essentially queer act in itself. His work follows in the footsteps of other visionary queer masterpieces such as Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, which also asks to "discover me so by faint indirections,/And when I meet you mean to discover you by the like in you".

Looking ahead to the future, the queerness of Blond(e) is almost certain to inspire a new generation of boundary-breaking artists (and more importantly, queer people of colour) who want to emerge from the long shadow cast by centuries of widespread homophobia, fear and ignorance over LGBT issues. It’s encouraging to see that defining yourself the way you wish to be defined and coming out on your own terms is becoming the new normal – both in the music world and in real life. Hopefully one day, gender fluidity will become as commonly accepted as genre fluidity, and straight artists such as Lady Gaga and Macklemore will not dominate the face of the LGBT liberation cause via their so-called queer anthems.

Above all, the personal expressions of queerness found in Frank Ocean’s art are remarkable in how intangible, fluid and elusive they remain, much to the dismay of homophobes. This messy contradictoriness in art and in life – a façade that’s ironically well constructed – is an essential part of his appeal, and is what makes his music so fresh and endlessly compelling to listeners both straight and queer, out and closeted. The only conclusion that we can now attempt to draw perhaps comes from Frank’s words alone. Musing on his fascination with cars in Boys Don’t Cry, the reluctant spokesperson reveals a mission statement of sorts: "Maybe it links to a deep subconscious straight boy fantasy. Consciously though, I don’t want straight—a little bent is good."