Short intro this month, as there are so many reviews to fit in. As I write, I’m just back from the first Small Press Day which saw numerous signings and other events in comic shops across the country, and for the second month in a row, found me spending too much money on comics with some time until payday. At the risk of sounding like a broken record, there are some really talented creators and dedicated publishers (and self-publishers) out there. As always, this month we have lots of books from a variety of publishers to help you disrupt your own finances similarly.

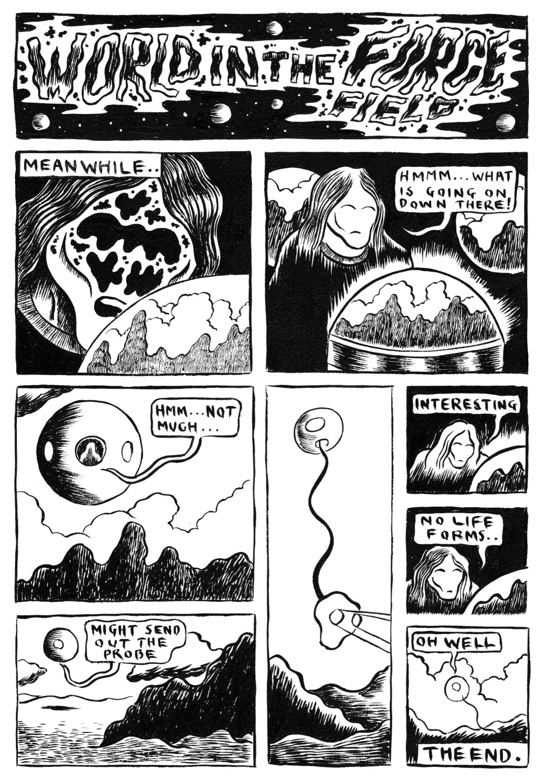

Alexander Tucker – World In The Forcefield 1

(Breakdown Press)

World In The Forcefield 1 is the first full-length comic from Alexander Tucker, published by Breakdown Press. The slim, risograph printed volume is as idiosyncratic as one familiar with his musical output would expect. Were it music, it would be closer to Imbogodom or his solo work than later Grumbling Fur releases – there are few concessions to the reader, and consequently it’s a very distinctive book.

It’s set in a fantastical universe, about two estranged brothers, with no normal beings depicted. Everything is very empty and quiet. The other characters are deities, giant godheads who strive to maintain a universe of boredom. Tucker’s narrative style is unusual – many pages have a title and finish with ‘the end’, as if they had been serialised first. Although this is not maintained throughout the entire book, we become so used to this early on that it feels as if all pages follow this style. As it changes, so does the ink, from blue to purple.

At the same time, he jumps back and forth, resulting in a fractured chronology. The prefacing of pages with ‘meanwhile, ‘later’ and ’somewhere else’ suggest complex philosophical perspectives, reinforced by references to eternalism elsewhere. By ending so many sequences of events per page, Tucker withholds the kind of narrative and in particular closure that audiences might expect, reflecting the godheads’ desires for boredom. This segmented, each-page-as-a-chapter nature of the story forces the reader to dive in, to accept and soak up the universe. The concept of boredom is important here; one page begins with a quotation from Joseph Brodsky: “For boredom speaks the language of time and it is to teach you the most valuable lesson of your life – the lesson of your utter insignificance”.

I could stare at and sink into Tucker’s art for hours. One very good reason to buy his music on vinyl rather than CD or digitally is to savour the large format covers. Many of his releases have artwork in a very similar vein, and some feature the same characters. Although his talents spread across both music and art, similar themes run through both, so there are playful references to his interests in tape manipulation and cut-ups, and his creative methods are consistent in all the media he produces. This is a singular work, one that demands acquiescence from the reader but repays by providing an immersive, striking world, intricately rendered. Pete Redrup

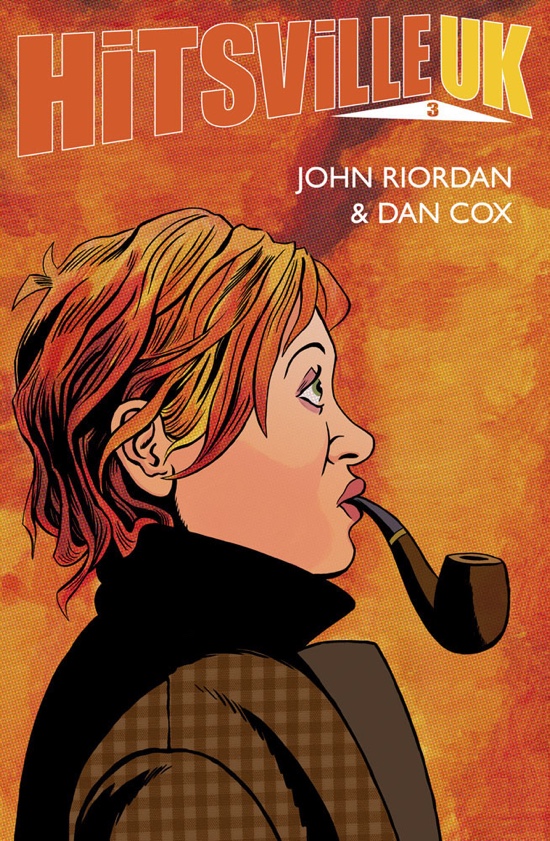

John Riordan & Dan Cox – Hitsville UK

(Self published)

Just a couple of days before meeting John Riordan and Dan Cox at ELCAF, I received their Hitsville UK back catalogue and immediately fell in love with the cover of #3. Riordan describes the series as "a psychedelic, pop art, musical soap opera in comics form (probably)”, which seems about right. It’s about a record label and their acts, and it is absolutely brilliant. The first comic illustrates why I often prefer to read single story single issues, or wait until a series is collected in a longer volume – there are so many characters to introduce that 30 pages is not really enough to properly get into it. This is no particular criticism of the writing, just a challenge faced by projects of this scale. Thankfully, there are now four issues available, with another planned for later this year, so newcomers don’t face a several month wait for the story to kick in after meeting the characters for the first time.

By #2 the narrative is fully underway. The writing is sharp, very funny (particularly the lyrics of the rap battles) and replete with social commentary, matched with outstanding art. #3 is my favourite. It has already been established that it has a particularly fine cover. Again, there’s plenty of social commentary, with references to austerity and some of the more charmless members of the Tory party. I’d actually forgotten about Grant Shapps until this. I can’t help but feel that if only a certain 52% of the voting populace had read and agreed with this issue, things might be very different. Cox is a gifted satirist; while the members of the neo nazi band Aryan 51 commit their terrible deeds(which includes being Nigel Farage’s estate agent), they discuss their hero Hitler, and their discovery that he was real, not fictional. The big shock is that he was German:

“German? But that’s foreign!"

"Worse, European."

“I thought we hated Europeans?"

Riordan’s art is superb throughout. It’s full of energy, with vibrant colour and extremely creative use of panels to enhance the storytelling. Matched with the writing, the subject matter and the witty, incisive political content, Hitsville UK is exactly the kind of comic we need right now. You can buy it from their website as well as a few comics shops including Gosh!, Orbital, Travelling Man and OK Comics, and you should. Pete Redrup

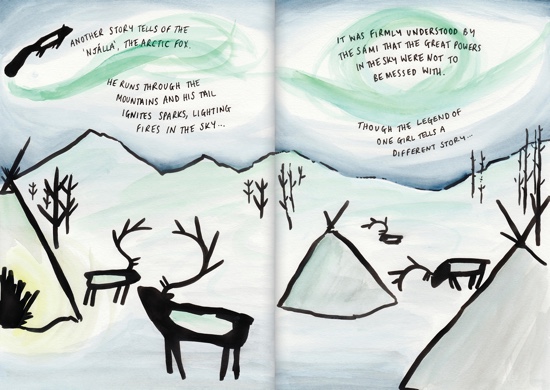

Rozi Hathaway – Njálla

(Self Published)

Rozi Hathaway’s new comic, Njálla, is clearly a labour of love. Inspired by travels in the region in which this is set, she used Kickstarter to raise the funds to achieve the physical quality she wanted, and this is indeed a lovely object, very tactile. The attention to detail is impressive, with my copy arriving wrapped in tissue paper matching the dominant colour of the book.

There’s little value to a beautiful book if the contents disappoint, but this maintains similar standards in both form and content throughout. It feels like a shorter comic than it is, because a lot of space is given over to creating atmosphere and texture rather than narrative. Hathaway uses bold, primal lines in the introduction, where we find out the setting and a little about the Sámi people who live in the Northern Scandinavian region, but once the story begins the line is pared right back to allow the beautiful watercolours to the fore.

It’s immediately clear that this is very skilfully constructed. Early on, a speech bubble is draped across two panels like a sound bridge, the way overlapping dialogue in a film can be used to establish a connection between two shots or scenes. Cinematic is an overused term, but undeniably one which applies here. This is not just because of Hathaway’s tendency towards full-width panels, but also as a result of the visual language used to connect them, and the utterly convincing lighting that she creates. There’s an image early on of two people sitting around a stove in a lavvu, the tents used by the Sámi, and the way Hathaway’s watercolours cast light and shadow is so effective. A heavily repeated motif is the use of circles. They are everywhere – in the lighting, the movement, the sky, the land, the interiors. They convey so many different things – the excitable energy of a child, the rough forces of nature, the Northern Lights, the enclosed space of a lavvu. It’s this natural, restrained quality that really stands out here – the minimal dialogue allows the images to tell the story, about a child, myths of the Sámi and the Northern Lights. Njálla is a confident, assured book, well worth tracking down. Pete Redrup

Rachael Smith – Artificial Flowers

(Avery Hill)

Rachael Smith’s latest for Avery Hill is another bright, colourful book in her distinctive cartoony style, with characters resembling those in her other comics. Here it’s more than just stylistic consistency, however, as this story features a cast from two of her self-published titles, Siobhan from House Party and Chris from I Am Fire, revealed here to be her younger brother.

Siobhan is now living in London in an expensive flat, funded by her wealthy parents. She’s trying to find success as an artist but her work is unremarkable. When her parents force her to take in her pyromaniac brother, just as she turns up a promising lead for an exhibition, she’s worried about how he will cramp her style. An argument leads Chris to release his tension in the only way he knows, and just as the gallery’s curator arrives to look at her paintings she discovers they’ve been burnt. To her surprise, the scorch marks are just what are needed to transform her art, and the book transitions to a farce as disaster becomes overnight success and a new creative partnership is forged, one that must be kept a secret.

Smith’s work is often very funny, with a great sense of comic timing, and this is no exception. It’s very well drawn, and the bright, breezy style makes it a fast read with a great sense of fun. At the same time, there are plenty more serious themes – artistic integrity, familial responsibility, personal growth, independence and honesty. This is an entertaining, enjoyable book, and another great addition to Smith’s body of work. Pete Redrup

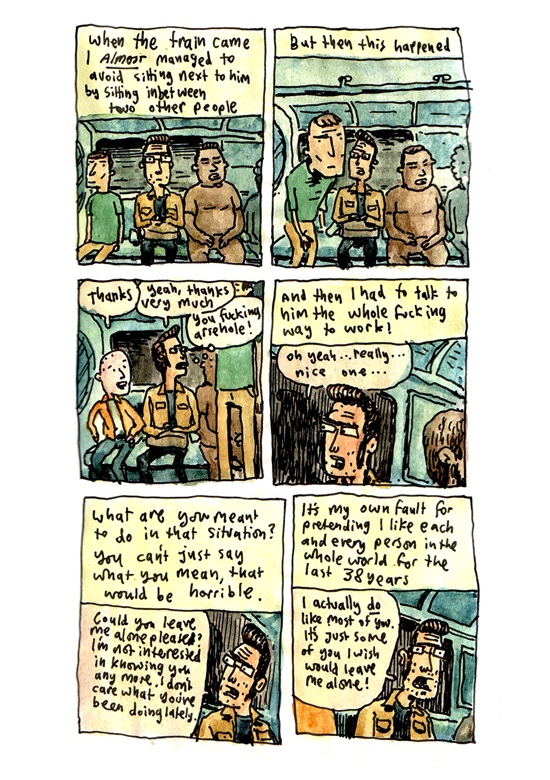

Alex Potts – Underpants

(Self published)

When I saw the title of Underpants, Alex Potts’ new self-published comic, my heart did not lift. As a parent of a four year old boy, I already have several underpants-themed books in my house and felt little need for more. Where are the tales of ineptitude and awkwardness I was hoping for, I mused? However, with a genuine belly laugh coming from the first page, I needn’t have worried. This is a collection of short strips from Potts’ sketchbook over a few years. Despite these origins, it’s pretty thematically coherent, often returning to the meaningless of life and the unanswerability of questions, although not in a serious fashion.

The depiction of Alex Potts here is interesting, someone governed by routine, a little bit antisocial, and given to pursuits like TV and internet browsing which he regards as ultimately fruitless, followed by bouts of self-loathing about this. My favourite strip, People Getting On My Nerves, shows him to be something like a British Larry David, desperate to avoid stop-and-chats with casual acquaintances but less adept at telling people to fuck off. Most strips are very short, one or two pages, and a couple are series of drawings of places he’s visited with neither characters nor dialogue. As befits the sketchbook origins, it’s a little rough around the edges, with a couple of spelling errors and a few crossings out, and there’s a mix of colour and black and white pages. The theme of being unable to think of an ending for a strip appears more than once.

Alex Potts is a very funny cartoonist in an understated way. His 2014 book A Quiet Disaster is one of my favourite Avery Hill publications to date, and if you don’t own a copy you are missing out. A collection of short strips like this is always going to be less satisfying than a longer work, but this is a decent comic nonetheless, and will do nicely while we wait for another longer piece. You can buy this from his website and also Gosh! and Orbital in London. Pete Redrup

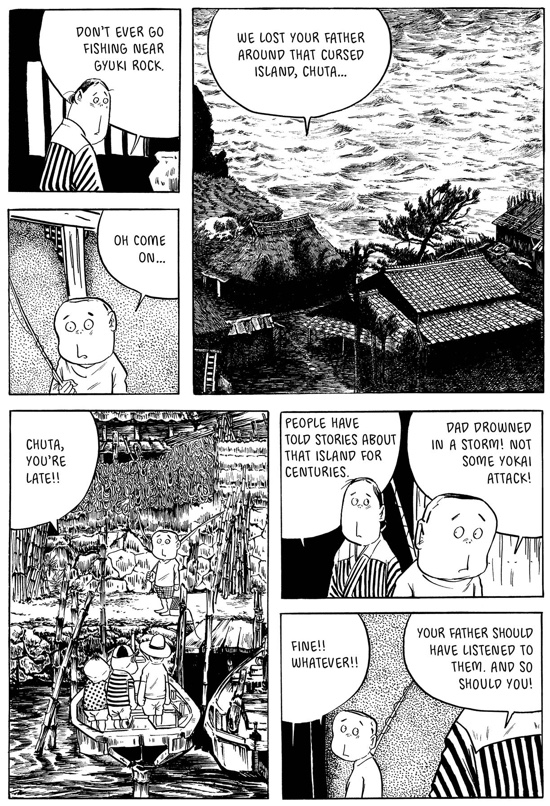

Shigeru Mizuki – The Birth Of Kitaro

(Drawn and Quarterly)

The Kitaro comics were Shigeru Mizuki’s most popular work, loved by people of all ages. The Birth Of Kitaro is the first in Drawn and Quarterly’s planned series of books, which are being published in in English for the first time. The format of small paperbacks is designed to be child-friendly, with puzzles and quizzes at the end, as well as an encyclopaedia of yokai. The translation by Zack Davisson is updated for modern readers, featuring phrases like ‘bwa ha ha’ and ‘nom nom’, although this doesn’t jar in any way, such is the style of the stories themselves.

The seven tales here all feature yokai, which translates as ‘mysterious phenomenon’ according to the afterword. Some are spirits, some are monsters, and they vary between good, neutral and evil. Many of these date from the Edo period, a time of great superstition. Kitaro himself is a yokai, on the good side. The first story is of his birth, in a grave following the death of his yokai mother. His father also dies, but one of his eyeballs comes to life, grows a body and follows him around to help. Another recurring character is Nezumi Otoko, another yokai, greedy but hapless with it and often in need of rescuing from the consequences of his ill-planned schemes. Kitaro’s role is one of helper, whether he’s digging Mezumi Otoko out of trouble or acting like a one-yokai A-Team, getting unfortunate humans out of trouble, frequently with his superpower hair.

In the second story Kitaro accidentally eats the face of a face-stealing yokai. It ends with Kitaro heading for the bathroom to shit the face back out – a good illustration of the general tone, which is very playful and often funny. The art varies. There are incredibly detailed establishing images, quite beautiful, long shots with very little negative space, much like those found in Mizuki’s other work. These contrast with the more event-driven panels, which tend to be much simpler and are much closer to the characters. This is a book that will appeal to children and adults alike, and I’m already looking forward to the next volume. Pete Redrup

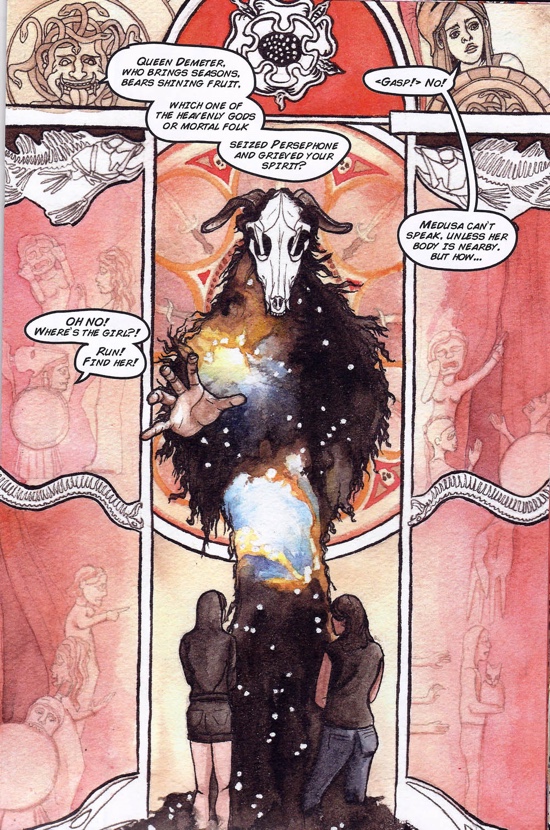

Kathryn Briggs – Triskelion – Meet your Maker

(Ess Publications)

I really wanted to like this arty comic that mixes media and myths. Taken a page at a time it is brilliant in places, reminiscent of David Mack’s Kabuki or the more abstract phases of Sandman. But Triskelion feels like Briggs took 10 years’ worth of sketchbook work, emptied them onto her scanner with a few things she found on her desk, some notes and quotes from a half dozen different A level courses, then photoshopped a dialogue on top.

The synthesis of hand drawn and digital is a lot better in this third instalment (Meet your Maker) than in the first two issues; the blacks are largely balanced and the layering is good, and as I mentioned, some of the pages are genuinely lovely. But the heady mix of styles does not translate into a cohesive whole, and the narrative thread does nothing to bind them together. Every few pages another mythical character enters and starts mouthing off about their significance, while the protagonist seems unable to decide if she has daddy issues or mummy issues, without ever actually addressing either and ultimately disappearing into a corner to sulk, only to discover more mythical characters there.

After three issues, we still haven’t been given any reason to connect with the characters, which oscillate between supposedly representing tropes and archetypes and moments of "real" dialogue where colloquialisms are thrown in to confuse matters. There are some interesting and important themes here (not least the kinds of power afforded women in historical texts and how it relates to our current roles and expectations), which I would love to see Briggs take on one at a time, rather than trying to, as I believe the Chinese say, eat the whole elephant with one mouth. Jenny Robins

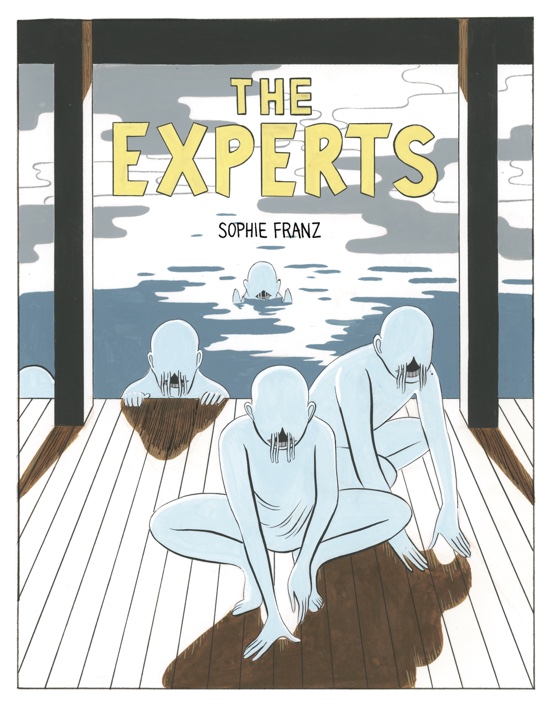

Sophie Franz – The Experts

(Retrofit Comics)

Two people, a humanoid fish and a dog inhabit a watery world, which Sophie Franz embellishes with flowing black lines and chalky hues of blue. These scientific researchers are alone out there in this seemingly barren setting, wondering why exactly they are in its presence, but Franz’s images, alive with engaging character designs and rich, natural colors, persuade a reader to settle into the scene and consider it.

You’re pulled in as the characters are, trying to make some sense of why strange aquatic creatures encircle their floating encampment, or what specifically these researchers are meant to study. The story employs a creepiness, and Franz follows the thought of obsession to show how it consumes the initial spark of curiosity. The characters (the obsessed) display signs of physical transformation to convey this experience, and by the end one of them clearly understands this trip has crossed a line, and knows it’s time to pull back and undertake something new (“I’ll brush up on my French”).

We never know who or what the creatures are, only that they are strange and arguably ugly or deformed. Franz, within the story’s first page, gives their perspective emphasis, though, as we see the characters from the creatures’ vantage point. They seem to take their time assessing their guests. It’s their territory, after all. But considering The Experts’ conclusion (a researcher joining the creatures), you wonder if these lifeforms are just the obsessed transformed, and despite appearing in control of their environment, are they not just consumed by it?

Considering their hold on the characters, and the little we concretely know, Franz suggests the creatures are the Experts of this story. They’re given the upper hand through mystery. But Franz places them in a similar position of the characters. They are watching a group of subjects. And if they are all in fact the obsessed redressed, then you could say they’re watching themselves, maybe or maybe not somewhat more aware. Alec Berry

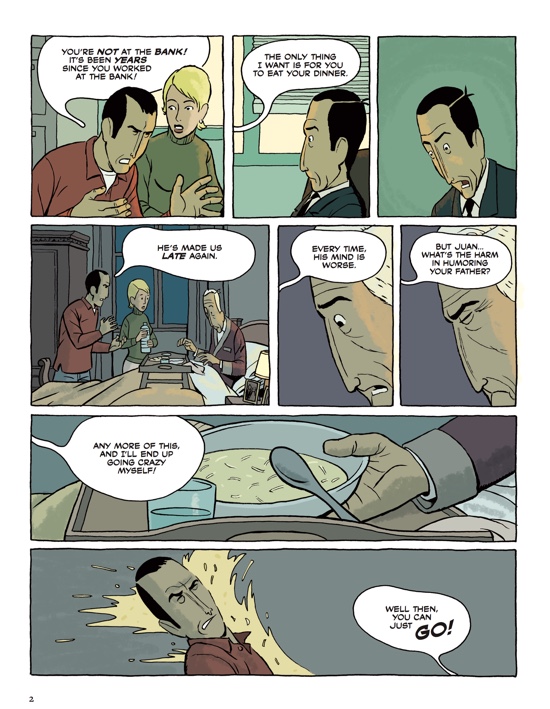

Paco Roca – Wrinkles

(Fantagraphics)

Wrinkles by Paco Roca is a high-wire act of storytelling that skillfully balances the inherent comedy of old-age and the sincerity of writing about Alzheimer’s. The winner of multiple international awards and adapted into an animated feature voiced by Martin Sheen and Matthew Modine, Wrinkles tells a story of friendship amidst a dwindling reality where the present is often confused for the past, words turn into alphabet soup, and the faces of loved ones disappear.

The book opens in what seems like an ordinary bank with Emilio, the manager, denying an exasperated couple a loan for their house. On the following page the bank disappears revealing Emilio in his bedroom, while the couple, Emilio’s son and daughter-in-law, argue over the severity of Emilio’s dementia. It is decided that the best place for Emilio is in assisted living where he meets Miguel, a con-artist that preys on the dwindling minds of other guests. Miguel escorts Emilio through the facility, but not before charging him a ten-dollar processing fee, showing him the various rooms, including the stairway to the dreaded second floor, a point of no return for guests no longer able to take care of themselves. As Emilio struggles to find his way around what to him feels like a labyrinth of undifferentiated spaces his only hope of staying grounded is through the comradery of his new friend.

With echoes of Ricky Gervais’ Derek, (although Wrinkles predates it), we get a glimpse into the terminal world of nursing homes, a place of inevitable deterioration, but not without new experiences. Emilio finds himself frequently in unfamiliar situations, even if they are routines he performs every day such as getting dressed, but with Miguel’s help the two build a bond neither had before. The relationship between Miguel and Emilio is clearly the main feature, but through their trials we become acquainted with a large supporting cast, many with their own amusing malfunctions. One of the most interesting of these characters is Mrs. Rosario, a woman that spends her time perpetually envisioning a majestic journey to Istanbul on the Orient Express. If Mrs. Rosario is any indication of what is in store for our own geriatric future, then let’s hope that we will also be cognisant enough to escape the confines of assisted living through the magic carpet ride of memory and imagination.

Paco Roca has already proved himself as one of the most talented comic storytellers from Spain, and next month we will get to read more from him in the upcoming anthology Spanish Fever also published by Fantagraphics. Matthew Laiosa

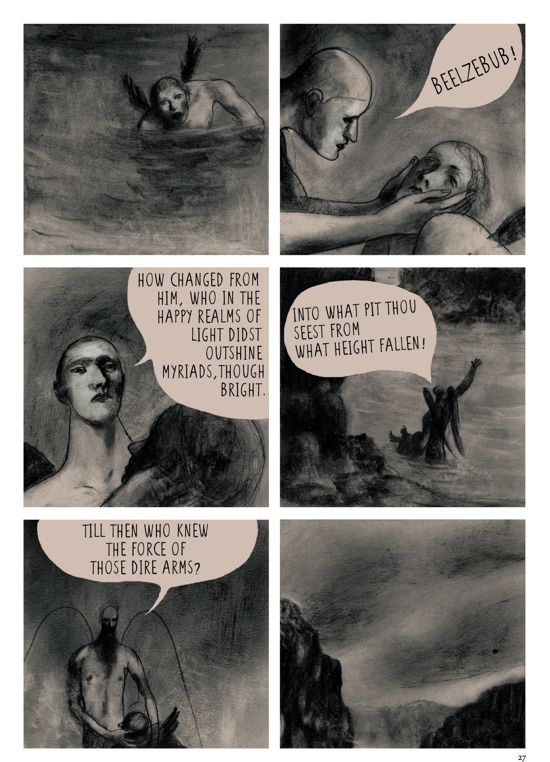

Pablo Auladell – Paradise Lost

(Jonathan Cape)

The reversal of villains into misunderstood protagonists has been a popular theme in recent years, especially in the books of Gregory Maguire. His stories playfully re-imagine familiar fairy tales so that we end up sympathizing with a character we’ve grown up to loathe. Milton’s nearly 350-year-old epic poem Paradise Lost, here adapted by contemporary Spanish artist Pablo Auladell, tells what might be one of the first examples of this now popular genre, and although Lucifer retains his faults such as his conniving nature and arrogance, what we come to discover is that God may be no different.

Written in verse, Paradise Lost tells the story of Lucifer’s fall from heaven, the origin of his rebellion, and the temptation of Adam and Eve. The book begins in the aftermath of a destructive battle where angels rise tarnished and broken from a world that does not yet seem fully formed. Having lost the battle Lucifer believes he can still win the war by polluting God’s creation in Eden. Lucifer takes flight on a journey meeting newly created incarnations of sin, death, and chaos, until he finally reaches his destination in paradise. The book jumps backwards and forwards in time so as Lucifer draws closer to his prey we begin to understand the reasons for his failed coup. There are no twists or spoilers to be had; Adam and Eve eat the apple, but what we discover for the first time are the untold machinations of God.

One thing that often feels dissatisfying about the graphic novel medium is the duration it takes to read a story. Multi-volume series and hefty tomes can take a few days to read, but in general, most ‘full-length’ graphic novels can be read in an hour or less. Even as a frequent reader of comics, I sometimes find myself skipping from word balloon to word balloon as the images pass instantaneously through my peripheral vision. Auladell combats this natural tendency of the eye by preserving Milton’s poetic language. I often found myself reading and re-reading the same sentence three to four times in order to fully extract meaning out of every word. This slowing down allowed me to take in the artwork in a way no other comic book has ever accomplished. By forcing my attention on the language, it allowed me to simultaneously linger on the images with their smudgy texture and faded color suggesting both an ethereal realm of higher beings, and the cracked and aged surfaces of a Renaissance fresco.

I am by no means a biblical scholar, so please forgive any unintentional heresy, but despite Lucifer’s arrogance I found myself allied with his desire to rebel against the absolute monarchy of God. “Better to reign in hell, then serve in heaven.” The book in no way pardons the acts of Lucifer, but it makes us wonder if God is enacting an omniscient plan then isn’t he also to blame? The only thing I can be certain of is that the lord truly moves in mysterious ways. Matthew Laiosa