There is more to say about Muhammad Ali than any sportsman or woman who ever lived. He occupies a huge space in the memory and culture of modern times. He mattered and matters still, more than every other boxer, footballer, golfer, athlete combined. There are those who believe boxing should be abolished, a barbarous hangover of more sadistic days of spectator sports, in which the aim is for one person to inflict grievous physical damage on the other. Ali’s career alone redeems boxing.

There’s a famous photo of him posing with The Beatles, recently arrived to conquer America, the Fab Four lined up like nervous skittles to be felled by a single Ali mock-punch. Ali was a hero to many musicians – from Prince to Perry Farrell, from Bob Dylan to Miles Davis. However, the photo shoot with a young, wisecracking up and coming boxer was an irritant to The Beatles, just another tedious chore on the endless publicity grind. Paul McCartney says he doesn’t even remember the photo being taken. As for Ali, it’s doubtful he ever took much of an interest in the works of Lennon and McCartney, his own, barely adequate musical sensibility revealed in a mangled version he recorded in the early 60s of ‘Stand By Me’.

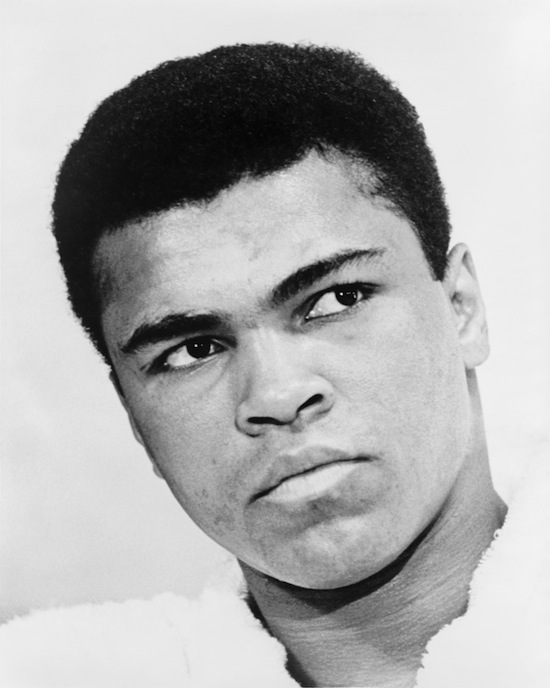

And yet, Ali, like The Beatles, was one of a handful of figures who precipitated the 60s. A figure of style, of wit, of grace, of volume, an embodiment of physical beauty and immense significance stamped indelibly on the collective consciousness now and probably for all time. In a monochrome, crewcut era he already looks coloured in by a modernity to come, a modernity he helped bring, already in 1975 when everyone around him is still trapped in 1960. Ali was one of the great liberators.

He was imperfect; there are aspects of what he said and did you have to overlook. He sided with the thoroughly dubious Elijah Muhammad over Malcolm X. Unlike Martin Luther King, he often espoused racial division rather than harmony; yet, paradoxically, he was always more derisive of his black opponents than his white ones, even mediocrities like Britain’s Richard Dunn. Joe Frazier in particular, taunted in frankly racist terms as a “gorilla” despised Ali for years, and not without reason. Frazier resented this lower middle class son of a Louisville signwriter setting himself as the true representative of oppressed black people, and casting Frazier, whose upbringing had been blue-collar tough, as an “Uncle Tom”. Some of his results, including the second Liston fight and the dubious “phantom punch” and a few generous points decisions in his later years are open to question. He could be a soft touch, prey to parasitical entourages, as well as the flattery of dictators like Idi Amin. As for his sexual politics, it’s probably best not to look too closely into them, though in fairness, whatever his religious beliefs, Ali did not make a point of imposing them on others.

Ali can more than be forgiven his faults because he transcended them, with his astonishing courage, his love of humanity, his vivid emotional intelligence, his sense of fun, and, despite the handful of losses he took in the ring, the sense of invincibility he exuded. Despite Parkinson’s syndrome, despite the terrible physical toll his boxing career took on his health, his life was a triumphant one. Asked if he’d do it all again knowing the consequences, he answered simply, “You bet.”

The story of how the boy who was born Cassius Marcellus Clay became a boxer has been told countless times; the theft of a bike that prompted him to take up boxing, the Golden Gloves championships and gold that followed in the 1960 Olympics that swiftly followed. Perhaps the most significant epiphany for Ali at this time, more so than his conversion to the Nation of Islam, however, was when he met a wrestler called “Gorgeous George” in Las Vegas. In the build-up to his bouts, George would pout with arrogant effeminacy, warn his opponents that they’d better not mess with his lovely hair, and promise to dispatch them because he was, after all, the greatest fighter in the world.

Ali understood the promotional value of presenting himself as the fighter people turned up to see because they wanted him to get beat. He overcame his essentially shy nature to recast himself as “Gaseous Cassius”, the braggart upstart, who flew insolently in the face of the macho expectations of the traditional boxer, doing all manner of “anti-boxer” stuff. He preened and praised his own beauty; “pretty as a girl”, as a result of avoiding the punches of his opponents. He composed rhyming verse and with hubristically predicted in which round his opponents would fall. All of this was matched by his boxing style; rarely if ever punching to the body, never looking for the one big punch; rather he jabbed with attritional effect, always to the head; messing with his opponents heads both physically and psychologically, with equal acumen.

It would work with Sonny Liston, considered as invincible as Tyson in his day, whom Ali challenged with typical insolence. “Ain’t he ugly? He’s too ugly to be the world’s champ. The world’s champ should be pretty, like me.” Liston had no idea how to cope with Ali’s “craziness”. Liston had been in prison; he knew it was always the crazies you had to fear. Ali sussed this weakness and exploited it, stalking and yapping and taunting at the “big ugly bear” Liston at every opportunity in the run-up to the fight. Come the bout, against the odds, young Ali outfought and out-psyched Liston, who sat slumped in his chair, refusing to come out for the seventh round. Ali, realising what had happened before anyone else, claimed the centre of the ring and, alarms aloft, floating on the balls of his feet, broke into a victory shuffle of butterfly beauty.

Ali’s braggart persona wasn’t merely a gimmick or psychological tactic. It had far greater resonance. Joe Louis, the “Brown Bomber”, had been World Champion between 1937 and 1949. He was the first African-American heavyweight boxing champion since Jack Johnson, who had enraged an openly racially divided America by first claiming the Championship, then easily beating the “Great White Hope” Jim Jeffries, brought out of retirement to give this black bounder a good hiding and reassure Americans of their assumptions about the physical and moral inferiority of negroes. Johnson added insult by flaunting the riches his purses brought him and taking white girlfriends, in an era when in some parts of America even to look at a white woman could earn a black man a lynching. Once the title was wrested from him, boxers like Jack Dempsey observed a colour bar to ensure that America would never again suffer the appalling effrontery of a Johnson. Joe Louis’s managers told him that if were to hope to be heavyweight champion, he would have to be the anti-Johnson, comport himself in interviews in the,“Yessuh”, Nossuh” manner of an acceptably non-threatening negro. He did all that; he joined the US Army too in wartime also, segregated as it was, without complaint.

Ali would be the anti-Louis. He wouldn’t just stand up for himself, he would stand up for all black people in 60s America still resisting the Civil Rights movement, all those forced to keep their heads down, never meet the eyes of their white masters, never answer back, know their low-paid, menial place. Ali’s voluble self-esteem was meant to be shared with them, by osmosis. Moreover, here was a guy who could beat up white men with impunity – the first man Ali beat professionally was Tunney Hunsacker, a West Virginia police chief. (They became friends). This was Ali’s first great significance.

Ali’s next great significance was his refusal in 1967 to be drafted for the Vietnam War, at a time when the accepted wisdom of the campaign was such that even Jimi Hendrix remained in favour of it. He objected on religious grounds; as a member of the Nation Of Islam, the only war in which he was mandated to fight was a Holy War declared by Allah or the Messenger, rather than the anti-imperial pacifism of the hippie dissenters. And yet, as he warmed to his theme, that he had “no quarrel with the Viet Cong”, and that “no Viet Cong ever called me n*gger” (this last line may well be apocryphal, but it summed up Ali’s sentiment nonetheless), it became clear that mixed in with his religious belief was a profound empathy with the darker-skinned peoples of the world, and an awareness of global injustice that transcended the powerful but morally vacant imperatives of US patriotism. For someone who had flunked the original draft test with an embarrassingly low score before they lowered their standards (“I said I was the greatest, not the smartest,” Ali sheepishly protested), he displayed not only courage but a geopolitical wisdom with which the Ivy League-educated would take a decade to catch up, and a compassion they’ve still yet to acquire.

Courage, however, was the main feature of Ali’s stance. Had Ali stepped forward and been inducted as “Private Clay”, he wouldn’t have faced any action, but, like Joe Louis before him, staged exhibition bouts, met and greeted soldiers with perhaps the odd photo opportunity showing him on guard duty. As it was, he stood to lose his heavyweight title as he approached the peak of his powers. Eventually, his stand as a conscientious objector was recognised on appeal but between 1967 and 1970, when he might have demonstrated his pugilistic skills at their finest, he was forced to rust.

He returned to the ring, a fraction slower and less butterfly-like but discovered an as yet untested ability to absorb punches. The most Homeric bouts of Ali’s career were in his later years, in which, fatefully, he shipped enormous punishment in the ring, first against George Foreman in Zaire in which, as with Liston, he used all his ring guile and psychological smarts to overcome a stronger and heavily favoured opponent. And then, there was 1975’s “Thriller In Manila” in which, in a third and deciding fight against his favourite nemesis Joe Frazier, he fought in 110 degree temperatures to near-death, collapsing in his corner moments after Frazier’s trainer, Eddie Futch, had refused to allow his fighter to come out for the 15th round.

Ali could have retired there but he enjoyed a strange twilight from 1975 in which, far from being a divisive figure, he became the most famous and most loved person on the planet. He fought daft bouts, against hopeless opponents like Jean-Pierre Coopman, the Belgian “Lion of Flanders”, who was so overjoyed to be in the ring with Ali he drank champagne in his corner for the five rounds the fight lasted before Ali decided to put him out of his happiness. He appeared as himself in a mediocre biopic, fought a farcical, mixed martial arts bout against a Japanese opponent Antonio Inoki which ended in a draw. He appeared on Parkinson a lot, and in adverts like this.

This is my Ali as a young boy; a non-musical pop idol, an imaginary uncle, with a twinkling, childlike fondness for kids like me, who, beyond his merits as a boxer, beyond even his moral bravery and political significance, was, simply, adored. Like Snoopy or Stevie Wonder, adored. He held unapologetically to the tenets of the Nation of Islam; yet he was more loved than any bland, distant, celebrity advocate of universal peace and harmony. He was loved because he was Muhammad Ali, a generic Islamic name which somehow belong to him alone. He was the most famous man on the planet yet he was accessible in a way even the most two-bit, management-protected, PR-cossetted celebrity is not today. Stories abound of him inviting photographers and reporters to hang out with him when they turned up at his training camp or on his doorstep. He himself, meanwhile, was prepared to do things, go places, visit folks in a way that would be beneath far lesser men than himself. And he did it so well. Who cannot adore this?

Come the 80s, following a sad end to his career as he exhibited the first signs of Parkinson’s Syndrome, a 38-year-old shadow of himself losing to Larry Holmes in 1980, he slipped from public view. The world of Thatcher and Reagan seemed to turn greedier and nastier in his absence. Thomas Hauser rehabilitated him with an excellent biography published in 1991 but so relatively low was Ali’s stock that following a book signing session in London, his minders didn’t even have a car laid on for him – they merely flagged him down a rickety black taxi. (“Guess who I had in the back of my cab today?”)

It was only in 1996, as he was invited to light the flame at the Atlanta Olympics, that Ali enjoyed the renaissance that has lasted to this day. A slew of Ali literature followed; titles like The Tao Of Muhammad Ali. While still alive, albeit physically fragile, silent and impassive in public appearances, Ali seemed to undergo a process of beatification. In attaining a sort of universal sainthood, however, Ali became de-radicalised, a process not helped by his image rights being sold in 2006 to a New York firm CKX, who also owned the Pop Idol Franchise.

Now that he’s gone, it’s time to reclaim Ali from those who would invoke him as a feelgood token, a mere inspirational meme. There’s a selected quote from Ali on the Apple homepage right now; “The man who has no imagination has no wings.” We should fix instead on Ali in his prime, as a mobile sculpture of sportsmanship as an art form, as the man who invented the modern idea of sports celebrity yet in no way resembles the say-nothing, sell-everything sporting heroes, not least in boxing, epitomised in the unabashed nickname of Floyd “Money” Mayweather. The Ali we should remember shouldn’t be merely as a source of apolitical aphorisms or bland messenger of peace but as a fighter and conqueror in a global struggle that is still ongoing. The Ali who said this.

"Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go 10,000 miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on Brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs and denied simple human rights? No I’m not going 10,000 miles from home to help murder and burn another poor nation simply to continue the domination of white slave masters of the darker people the world over. This is the day when such evils must come to an end. I have been warned that to take such a stand would cost me millions of dollars. But I have said it once and I will say it again. The real enemy of my people is here. I will not disgrace my religion, my people or myself by becoming a tool to enslave those who are fighting for their own justice, freedom and equality… If I thought the war was going to bring freedom and equality to 22 million of my people they wouldn’t have to draft me, I’d join tomorrow. I have nothing to lose by standing up for my beliefs. So I’ll go to jail, so what? We’ve been in jail for 400 years."

The Ali who showed us the edge of hell but who brought as much joy as anyone to this world in my lifetime. The Greatest.