Photograph by Alex Lake

We meet in one grand old landmark, to discuss another. The Landmark Hotel, formerly The Great Central, is a magnificent Victorian redbrick pile in Marylebone. It’s visible in the opening credits to A Hard Day’s Night, with The Beatles fleeing from rabid fans to the station across the road. Between 1939-1945, it was used as a military convalescence home: a place of refuge, much like the album we’re here to discuss, for those who have been through the wars. Later, when it served as the headquarters of the British Railways Board, rail workers nicknamed it ‘The Kremlin’.

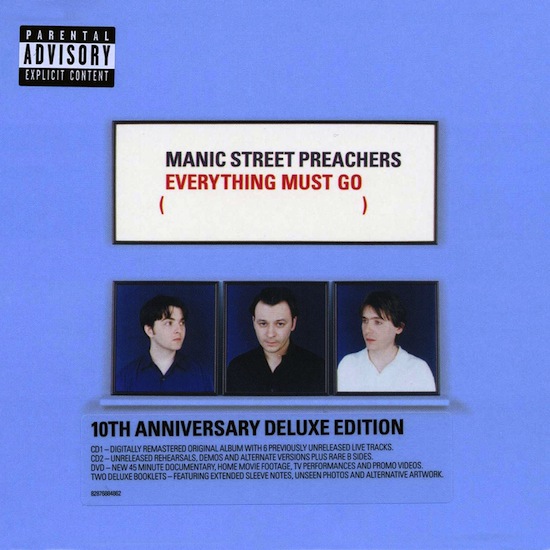

Everything Must Go is the Kremlin of Manic Street Preachers albums: an enduring monument, ever-present in every era, impervious to regime change. (I’d call it ‘The Crumlin’, if that wasn’t too niche a Manics in-joke and too Wales-centric a reference.) Since its release, there’s never been a Manics concert when they haven’t played at least one (and usually several) of its tracks. This year, its 20th anniversary, they’ve been performing it in full on a wildly successful tour, taking in huge venues like Liverpool’s Echo Arena and Swansea’s Liberty Stadium, as well as two nights at the Royal Albert Hall. It’s their second retro album tour in a row, having recently revived its harsher and harrowing predecessor The Holy Bible. They’ve also re-released it in various deluxe formats (having already released an earlier 2CD edition on its tenth anniversary).

Trailed by the single ‘A Design For Life’, a stirring anthem of working class pride which very nearly topped the charts, Everything Must Go, with its accessible melodies and widescreen wall of sound production, was the album which saw the Manics – buoyed by Britpop while never fully being co-opted by it – become the million-selling act they’d always promised they’d be. There’s an inherent irony in the fact that an album which expressed the Manics’ desire to be “freed from our history” is now an immovable pillar of that history, to which they are, whether consensually or not, shackled.

This time around, upon their own insistence, Bradfield and Wire are interviewed about it separately, but for ease of reading, their quotes are presented together. They know each other so well that even when separated by floors and walls, their answers second-guess each other, complement each other, follow on where the other has left off. Sean Moore, as usual, is the silent partner: there’s a comedy moment when I catch the drummer in the doorway just as I’m arriving, sneaking out of the hotel minutes before interview time. It would be awkward if we didn’t both understand the situation implicitly.

The rooms in the Landmark are luxurious by anyone’s standards: even the bedside lamps look like the Champions League trophy. Wire’s, as you’d expect, is impeccably tidy, but James’ is slightly more lavish. “How come your room is nicer than mine?” Wire asks him with mock-jealousy. “This is where they put you if you’re a smoker,” comes the reply. Bradfield has eerie choral music playing on the iPod, and a copy of Guitar Player magazine lying around with a picture of Ritchie on the front. (Blackmore, that is, of Rainbow, whose ‘All Night Long’ riff James has been playing at gigs lately as the intro to ‘You Love Us’.)

Midway through James’ interview stint, there’s a knock at the door. It’s Wire, carrying a bag of Everything Must Go reissues to be autographed. “The silver pen’s in here,” he tells him. “You’ve just got to give it a little squiggle so it warms up.” Bradfield turns to me. “Now you can tell the fucking Twittersphere or [Manics fan site] Forever Delayed that we DO fucking sign them!” There’s a laugh, and a twinkle. “Fucking moaning bastards…”

Stepping out onstage on this tour, knowing that you have such a solid gold, much-loved album in your armoury, must be quite a reassuring feeling.

“It’s a completely different experience from going out and playing The Holy Bible every night,” James confirms. “Playing The Holy Bible, knowing you’ve got to hit your straps, and ‘Ifwhiteamerica’ is so early in the set, which is one of the most challenging songs in terms of locking it all in, with the time signatures and the words. And the first track is ‘Yes’, with all the fucking words in it… The only feeling I can compare it to is when you have your first proper fight at school. ‘See you after school!’ kinda thing. And you’re thinking about it all the way through Geography: ‘FUCK, how am I gonna win this?’ And every night, going to do The Holy Bible, was about being scared of the mechanics of performing it, and being older.”

Wire’s view is similar. “It couldn’t be more different from doing The Holy Bible one. Which is, on every level, mentally, physically, technically, really hard to play. Obviously it was ten times harder for James, because he was singing across it as well as playing, but you find yourself in awkward positions, playing the bass. Your muscles go into weird shapes. There are a lot of important basslines on The Holy Bible, there’s a lot of responsibility. But I don’t think The Holy Bible was nostalgia. It was us trying to get it out of our system. And it didn’t feel like nostalgia because it was quite fucking vicious – you had to get into that state of mind. With this, I make no apologies, this is us wallowing in something, that melancholic euphoria that we’re very good at.”

“With Everything Must Go,” says James, “you haven’t got that fear. And with nearly every gig I’ve ever done, from the first gig we ever did at Crumlin Railway Inn to the last gig at the Royal Albert Hall, I have terrible, terrible feelings before I step on stage. It’s never ended. I always think ‘Why am I fucking doing this? Can’t we just be The Beatles and be a studio band now?’ Then usually, five minutes in, when it’s going well, it’s ‘I’m on top of the world, ma!’ But for these shows, those feelings have slightly receded and you can go onstage and get dragged along with it, just fly with it. It’s easier to play – the technical challenge isn’t as daunting – but, you’re aware that the audience who have come to see it want to hear the album as it was, so you want to craft it a bit more, so there’s that pressure.”

I was really struck by seeing the video for ‘A Design For Life’ during the Royal Albert Hall gig, with the footage of Last Night Of The Proms, filmed in the same place, and thinking, ‘Here we are’, in the actual place…

“Here we are!” Wire smiles. “Entertain us… Yeah, the first time we played the Albert Hall, in 1996, I hated it. I was in a right old fucking mood, and I did not enjoy it one bit. But I loved it this time. The gig in Liverpool was amazing, really special, and we invited all the families of the Hillsborough 96. From the very first gig, in Tallinn in Estonia, it’s been spot-on, right through.”

A lot of the songs on the album have been in or around the setlist for years, of course.

“Yeah,” concedes James, “but there’s stuff like ‘The Girl Who Wanted To Be God’, ‘Removables’ we haven’t played that much, or ‘Interiors’, and we haven’t played ‘Australia’ much since the late Nineties, and ‘Further Away’ we haven’t played much. But you’re right, stuff like ‘No Surface All Feeling’, ‘A Design For Life’, ‘Everything Must Go’, ‘Kevin Carter’, ‘Small Black Flowers’, we’ve played the hell out of.”

“That album just breathes, sonically and lyrically,” says Wire. “It’s a communal intake with less intensity than some Manics gigs, if you know what I mean. But we ramp it up so much in the second set, with the production and the visuals which are fucking stunning. It has the scale that we always wanted. And knowing you’ve got that second set in your back pocket, doing ‘You’re Tender And You’re Tired’ which we haven’t done for fucking ever. and… ‘NatWest Barclays Midlands Lloyds’…”

When I saw ‘NatWest’ on the setlist for the second half of the gig, I thought ‘Really?!’ Of all the songs on Generation Terrorists, I’d never have chosen that one. But in the flesh, it properly rocks. I was surprised.

“I actually feel really proud doing that, as well,” says Wire. “Because you still get all these fucking idiots in the broadsheets saying ‘Oh it’s clunky…’ It IS clunky, because we’re dealing with a massive topic (the banking system’s ruinous effects on people’s lives), which we foresaw, and you didn’t!”

There’s no sense of eating up your greens before you’re allowed your dessert, with this show: you have one crowd-pleasing set (the album) followed by another (the hits).

“I do have respect for someone like Radiohead,” says James, “who will be quite obtuse about their approach to entertaining their crowd. They might make what [music critic] Stephen Dalton would call ‘braver decisions’. And we’ve always been like ‘Nah, let’s get it moving, let’s get the party started!’ So, starting the show with ‘Elvis Impersonator’ is quite unnatural for us. Because it is almost a quintessential Seventies-esque album-starter. It’s not a singalong.”

(It sort of is…) Radiohead, of course, have never had the same sort of constant push-and-pull between the polarities of the commercial and difficult parts of their catalogue.

“No, and different bands are born from different mindsets. I’m at my happiest when the crowd are moving with each other, and they’re connected, and to be frank, it feels like a party’s breaking out, a bit. But a slightly violent party. I like it when rock & roll feels like it’s boiling up. And the crowd’s boiling up, and we’re with them, getting dragged into this kind of… nice fight. Whereas Radiohead want people to think, when they go to their gigs. I couldn’t give a fuck if someone’s thinking when they go to one of my gigs. I’ve always wanted it to be, as my dad would say, ‘C’mon, let’s have a go!’ One of them is not right and one of them is not wrong, but it was in our nature to always want to do a gig that was just entertaining.”

Another highlight is the surprise cover of Fiction Factory’s hit from 1984 ‘Feels Like Heaven’, which the Manics have also recorded for Dermot O’Leary’s BBC Radio 2 Live Lounge.

“I must say about ‘Feels Like Heaven’,” says Wire, “that it’s just about our love of pop music. People can talk about alternative music and I couldn’t really give a fuck, but when you’re young and a pop song just fills your heart, there’s nothing like it. Although there’s a really dark lyric: ‘twisting the bones until they snap’, and all of that. But that’s what I miss about modern music. My love of pop music is just gone. Lyrically it’s inept and vacuous, and musically the generation gap’s perhaps too big. But I loved my mum’s fucking Demis Roussos and ABBA albums. That’s the sadness, for me, of what’s missing from modern pop music: that song that just fills your heart, like ‘Into The Groove’ by Madonna did. You don’t have to like the artist, or what they stand for, but just a song that grabs you. ‘Groove Is In The Heart’ by Deee-Lite. I just don’t get that any more. I’d struggle to find the last one. Maybe ‘Umbrella’ by Rihanna (which the Manics covered for a charity album). I’m not saying it’s all bad music, but just that shiny pop music where you’d put something on ten times in a row. You know, more than anyone, there’s always been that love of a pure pop song which runs through the Manics. A genuine affection, not for a band you like or a style you like, but be it ABBA or Glen Campbell or the fucking Wombles, there’s always been that love.So when people talk about Everything Must Go being ‘commercial’, that’s always been innately in us.”

The Manics have already spoken about the making of Everything Must Go a thousand times, and even made two separate documentaries about it, so we don’t dwell on it unduly. But the first moment when the outside world even suspected that a fourth Manic Street Preachers album was being made occurred when a sweet acoustic cover of BJ Thomas’ ‘Raindrops Keep Falling On My Head’, featuring a Sean Moore trumpet solo, suddenly appeared on the Help album for the War Child charity on 9 September 1995, the concept being that the contributing artists had to record a song in just 24 hours, five days before its release. It was the first Manics recording since the disappearance of Richey Edwards in February, and the first smoke signal from the Vatican of the Manics camp to suggest that the band intended to carry on without him.

“We were committed to the War Child thing,” James recalls, “and we asked ‘When’s it got to be delivered?’ and they said ‘Wednesday’, and we said ‘But we’re in France on the Tuesday…’, so we knew that the next morning, after we arrived in France to work on the album with Mike Hedges, we had to wake up, do ‘Raindrops’, and just FedEx it over. So, us putting it out wasn’t planned as us saying ‘We’re OK, guys!’, but the deadline was the next day after we’d arrived in this place, for some kind of new beginning. So it forced us to get started.”

“I don’t know if the other bands on the War Child album did,” Wire verifies, “but we really did record it in 12 hours and bung it on the ferry to be mastered. I totally agree with what you’ve said about ‘smoke signals from the Vatican’, but I’m trying to think. Had James already done that, a few times live, acoustically? Yeah, that and ‘Bright Eyes’.”

“The first time I ever played it was,” James believes, “those Bangkok gigs we did, before The Holy Bible was out, in my solo bit in the middle of the gig, and those gigs were fucking brilliant. By the time the three Astoria gigs came around, I was doing ‘Bright Eyes’ instead. (Fact fans: he did ‘Bright Eyes’ twice and ‘Raindrops’ once.) In our downtime as a band, sharing time with each other on the tour bus in little splitter vans, or back in the rehearsal room in Cardiff, or we’d go back to Richey’s house or my house, we would have gloriously un-Manic-esque moments, where we’d watch Butch Cassidy And The Sundance Kid, because we all loved it when we were kids. It was a proper Easter film. And we all loved the sepia freeze-frame at the end, and we all loved that song. So we’d be watching really good Seventies films, or talking about boxing or rugby, or watching overblown music movies like The Song Remains The Same over and over again, travelling from Stoke or wherever to London, and when the VHS finished we’d put it on again, then we’d all fall asleep. We’d have these little touchstones that were off-piste from the Manics message, so to speak. I remember filling in one of those Thrills questionnaires in the front of the NME, early on, and listing Eddie Van Halen as one of our heroes because he was so pretty and so cool. We were already off-message, even then. And among all the tablets of undeniable truth that we would send down in our interviews and our songs, there was a playful side to us. The solo bits started happening because Nick wanted a costume change, and that song was just a bit of relief, really, perhaps showing that we were a bit more human than we seemed. Because we knew The Holy Bible was looming and there wasn’t going to be much room for levity.”

The choice of Mike Hedges as producer was crucial to the album’s sound. “We’d been through the thing of Richey’s disappearance,” James remembers, “and subsequently deciding that we needed to do something, so we wrote the song. ‘A Design For Life’, which started the ball rolling. Then we got in touch with Mike Hedges, who came to Cardiff with us. We’d wanted to work with him on The Holy Bible, but he wasn’t available. Meeting him was so brilliant, because he’d done so many records I loved. ‘Swimming Horses’ by the Banshees – what a fucking record that is! I remember there was a kid at school who was, let’s say, not unhinged but definitely on edge. And he’d gone goth-punk, and he brought a copy of ‘Swimming Horses’ 12 inch to school and I sat on it by mistake. And he wanted to kill me. And I remember thinking ‘You really care about that record. I’m gonna have to chase that record down…’ And Mike had also done the Associates and ‘Story Of The Blues’ by Wah!, I’m talking about the records he’d done with strings on. So it was a no-brainer that we wanted him to do Everything Must Go.”

There’s a great story about Hedges greeting the band with his hand in flames. “I do have the memory,” reminisces James, “that we were on our way to Chateau de la Rouge Motte, in Domfront in Normandy. It’s this little provincial capital, and not many people live there. There was a strange atmosphere when we travelled there, because there was a sense that we were embarking on a journey, physically and emotionally, which was, as my dad would say, ‘shit or bust’. If it didn’t work out, there was a chance this could be our last album. We got there in the still of night – it’s quite an arduous journey to get there, for some reason – and once we got there, at the top of this hill, it was a bit ramshackle, sort of faded, ex-glorious chateau. At the top of the driveway there was a fountain, and gravel, and this chateau which was big and quite spooky in the dark, and we could just see this figure in the darkness, and we could see something was on fire. And as we got closer, we realised it was Mike’s hand. The car was moving slowly, and he was like ‘Fucking come on, come on!’ We said ‘Are you OK?’ cos we’d only met him once before this, and I’d got absolutely hammered with him on Brains SA in Cardiff. But he’d dipped his hand in calvados and set it on fire, because that’s how he greeted every band. So that was a good sign. His first line was ‘I’ve got a few hot French tarts waiting for you!’… and of course they were quiches. And it just felt like home, immediately.”

Presumably it was good to get away from the UK, after everything that had gone on with Richey’s disappearance and the media attention that brought with it?

“It was. Of course, any young musician now won’t understand this, but we’d been in the middle of this shitstorm of what had happened with Richey, and previously lots of other stuff too, and we were inveterate music press addicts, so even if you’re in the middle of something, you can’t help buying Melody Maker and NME and Select, and it was good to be away from all that, and not have a chance to buy them. No-one knew who we were, in France: we were lost in France, as Bonnie [Tyler] would say. Because it really was ‘press = pressure’. You’d go to Cardiff and there would be NME moles in Cardiff, even. So it was good to be away from all that.”

“Even though it was the pre-digital age,” says Wire, “it was a heavy time for us, and it was shit.”

You couldn’t open a music paper or even a newspaper without being reminded of it.

“Yeah, especially when you started getting all the ‘sightings’ popping up. So to get out there and be welcomed by this father-like presence who’d made so many amazing records was wondrous. It was such a magical time, turning up, not knowing anyone, no-one knowing us, no magazines to buy or anything, none of us spoke any French… James will undoubtedly say it was his favourite studio ever.”

Some of the songs, of course, had already taken shape while Richey was still around, to varying degrees. Let’s nail that down, once and for all.

“Right then,” says James, “I’ll get this straight. When we got to House In The Woods studio in Surrey, obviously prior to Richey’s disappearance, in that session we demoed ‘Further Away’, we demoed ‘No Surface All Feeling’, and ‘Small Black Flowers’. We also demoed some B-sides: ‘Dead Passive’, which is rubbish, and ‘No-One Knows What It’s Like To Be Me’. Also, written but not demoed, because we ran out of time to do demos, were ‘Elvis Impersonator: Blackpool Pier’, and part of ‘Kevin Carter’. I’d played those two to Richey on the acoustic. But it was, you know, ‘It’s a bit like this, I’m not sure yet…’”

“’No Surface All Feeling’ already existed too,” says Wire. “although we hadn’t recorded it. But a lot of the other tracks, ‘A Design For Life, ‘Everything Must Go’, ‘Australia’, ‘The Girl Who Wanted To Be God’, ‘Enola/Alone’, ‘Removables’, all came together post-Richey.”

There’s a recent interview in which James compares Rewind The Film, the Manics’ entirely acoustic 2013 album, to Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska…

“Not compared,” he corrects me, “but I said that Nebraska had always given us an ambition to make an acoustic album.”

But if we can follow the Springsteen analogy through, Everything Must Go is the Manics’ Born To Run, with that cranked-up Spector-esque sound.

“There used to be a nightclub in Newport called Rudy’s,” says James, “which was a soul club, and me and my girlfriend of the time used to go down there. And they’d play lots of quite obscure Tamla Motown. And Northern Soul, which I’m not such a gigantic fan of. But they’d play stuff like ‘The Hunter Gets Captured By The Game’ by Marvin Gaye, or ‘I Can’t Get Back The Love I Feel For You’ by Syreeta Wright, really select, choice stuff from Motown. And I was always a massive Motown freak. My mum had lots of Motown in the house. I just loved the strings and the arrangements. It was the same with ELO: I’m on record that they were my first musical love. I presented Jeff Lynne with a Lifetime Achievement award at the Q Awards about 12 years ago. So, that love of strings in music was always there, for me. And my mum was a bit of a Sinatra fan, and ‘Summer Wind’ is one of my favourite songs: the strings on that were just transcendent. And yeah, ‘Born To Run’ as well. Because that record took ages, and Springsteen was obsessed with creating a soundscape, he really was. And I wanted that, for Everything Must Go.”

“I think the two big changes from The Holy Bible”, says Wire, “are that Everything Must Go was really natural, so it’s less stylised, even though it has the strings all over it. It doesn’t sound like we’ve searched for a fucking sound that’s like Magazine, or Slash. It’s very naturalistic. And apart from Richey’s lyrics, there are less words. And the Spector thing was massive for us, and in interviews James would always go on about his love of Tamla, and Phil Spector. And Bruce Springsteen, while you’re at it. So that’s all in there. It’s on a grand scale. It’s probably our biggest-scale record.”

Despite the orchestral trappings, the sound began, according to James, with the drums as the first building block.

“When you go into the studio sometimes, you’re moving the drums around in a really stupid muso way, because where you put the drums in a room affects how they sound. And I loved records like Pornography by The Cure and Joy Division records and Wire records and Magazine records and Banshees records and Wah! records and Associates records where everything starts with the drums. You make them sound boxy, and you put a harmonizer on them, and sometimes you make them sound like it’s been recorded by a computer. And on a lot of those New Wave records, the drums are optimised to hell. And that’s a philosophy of recording: you record the drums in a very tight way, then put effects on them, to make it sound slightly other-worldly or cold. Which is what a lot of those post-punk records were built on. But then you’ve got another philosophy of recording where you want an absolutely top-class engineer and producer to record things as purely as they hear them in the room, and put that through the mics, and record them in a beautiful cultured way. And Mike Hedges could do both: he’d done an awful lot of post-punk stuff, but he’d also worked for The Beautiful South, and ‘Yes’ by McAlmont & Butler, and he’d recorded things in a beautifully natural, Abbey Road-esque way. We used a mixing desk from Abbey Road, the same mixing desk that that Badfinger had worked on, that Dark Side Of The Moon was recorded on, and I think some Beatles stuff, the Hollies… It was the Dark Side Of The Moon desk. But the way it was recorded was so important. Mike said ‘Everything’s got to breathe. You’ve hit a peak, as songwriters, and it’s gotta be natural.’ He said ‘Its got to be produced trashiness. I still want there to be that element of trashiness when I’m stood in the room with you, but it’s got to be produced trashiness. No fucking skulduggery, it’s just pure.’”

The visuals of the Everything Must Go era were notable for their cleanliness and their simple, monolithic quality. Essentially, they were New Order. (The embossed metallic sleeve of ‘A Design For Life’ directly echoes New Order’s first post-Ian Curtis single, ‘Ceremony’.)

“Yeah,” Wire admits, “The parallels with New Order/Joy Division were obvious.”

James agrees. “Aye. It was all Nick and (designer) Mark Farrow’s doing. Mark Farrow was an amazing bedfellow for Nick at that point. Because with Richey taken away from the equation, in a visual sense – you know you can’t use him in the artwork – it’s a bit like losing Messi in a football team. And that’s why we went to Mark Farrow. Who had a bit of a Factory Records backstory to him, as well (Farrow’s first album sleeve design was for Factory band Stockholm Monsters in 1982). For Mark Farrow, in terms of his style, it all started with Unknown Pleasures and Closer. We knew that he would be on board with that message of trying to create a facade that the music could hide behind. He knew that we wanted to take the pressure off ourselves. Because Richey wasn’t there any more, and when you got to the nuts and bolts of being in a band again, you realised how hard that is.”

And what about the way you dressed? Make-up and paramilitary uniforms were out, and you went for simple casual clothing. It’s as if you wanted to put no barriers whatsoever between yourselves and someone liking you. As if you were determined not to shoot yourselves in the foot. Because previously, circa Generation Terrorists, your look was partly inspired by Guns N’ Roses, which was a calculated decision based on the fact that they’d been the biggest band in the world for a couple of years, but the timing was disastrous, because that look went out of fashion…

“…straight away!”, interjects Wire. “Manics At C&A!”, jokes James. “In terms of analysing it, you’re right: there is a serendipity to us doing that, because suddenly, loads of people went (puts on blokey Cockney accent) ‘Oh yeah, they’re alright, I don’t mind these geezers…’ But it was also a practical thing, because you used to have James and Sean down the middle, and James is the utilitarian ditch-digger, and Sean behind him is the man of few words who powers everything, and then you had the two wingers. There was a bit of Cheap Trick about us, definitely. But I think he thought ‘If it’s just me, on one side, like that…’ Suddenly it’s not the flying wingers, and it’s just ‘I’m the weird bass player from Sweet.’ He wasn’t comfortable doing that on his own, at that point.”

Was there an actual sit-down meeting where matters of image were discussed? “No, none at all. I remember there were conversations before the photo session we did with Rankin for Everything Must Go, like ‘What are we gonna wear?’, and he was just like ‘Be normal.’ So it was us diverting the pressure onto the music. Because we knew we’d written pure songs.”

“It’s true what you say about putting no barriers up,” says Wire. “For those early moments, that felt like the right thing to do, to not be that band who did The Holy Bible. It wasn’t a conscious decision to dress down. But there was certainly an idea of, at least for me, just to fucking rein myself in for six months at least. It didn’t last much longer than that. It’s something we needed to do. I struggled with it, a little bit. And by the end, there was a see-through camouflage dress. And by the time of the second Brit Awards in 1999 I was wearing a leopard-print top and skirt, and skipping with a skipping rope…”

The overriding theme of the album is escape. It’s in ‘Australia’, it’s in ‘Small Black Flowers That Grow In The Sky’, and obviously the title track…

“It is, yeah”, says James. “I did want to escape, probably. I wanted to be lost in the music, a bit. And it was hard to admit that, in interviews, because to say a line as trite as that, back in the days of quite harsh editorials in the Melody Maker and NME, I’d have been slaughtered. That was good, by the way: it was good to have that pressure of having to watch what you said and not be too cliched and hackneyed. But I can admit now, I did just want to enfold myself in the music and get carried away with it.”

“There’s a sense of escape,” agrees Wire, “but also a sense of carrying on, that comes with Everything Must Go. Of redefining yourself, post-trauma. A lot of people paint the album as some sort of old-school Labour manifesto, but that’s only one song. The emotion is incredibly raw. The Holy Bible is too, in a different, twisted way. But stuff like ‘Everything Must Go‘ and ‘Enola Alone’ is actually talking to your fucking fanbase. And ‘No Surface’ is very open. I didn’t realise I was being that open, when I was writing those words.”

That said, Everything Must Go wasn’t the clean break from The Holy Bible that it’s often portrayed as being (or, indeed, that it attempted to presented itself as being). There are references to the Holocaust, to genocidal wars in Africa, to dementia, to Sylvia Plath, to painters and photographers, and a song in which Richey empathises with a trapped zoo animal (instead of an anorexic or a prostitute). The sound may have changed, the themes hadn’t.

“Yeah”, says Wire, “’Interiors’ is about an artist with Alzheimer’s not knowing what he’s painting. It’s a pretty fucking heavy theme. And I’ve said it about ‘Small Black Flowers’, the fact that a million people that year bought an album with the darkest line in rock history: ‘Harvest your ovaries, dead mothers crawl.’ You would see couples swaying with each other at gigs, to that!”

“There is a continuity, yeah,” says James. “At the start, Nick and Richey literally sat down together at a desk to do the writing, and even though Nick’s lyrics outweigh Richey’s for an obvious reason, there’s still a good draft of Richey’s lyrics on there. And even though they didn’t write together at a desk any more, they still counterweighed each other beautifully.”

The band’s politics hadn’t disappeared, either. ‘A Design For Life’ wasn’t a complete one-off.

“At those first Brit awards, I did make that speech about comprehensive schools, which was a bit of a radical moment. There used to be 12 million people watching the Brit Awards then, and to say ‘This is for all the comprehensive schools in Britain’, for producing the best music and art and the best boxers and stuff…”

It would be even more of a radical statement now, in an age when the privileged have taken over pop and the other arts.

“Yeah it would, because at least there were avenues out of it then. But I remember performing ‘A Design For Life’ at the Brit Awards, with all the screens behind us, and thinking ‘We’ve taken over, a bit, here!’”

When all of this was going on, the Manics were 26 and 27 years old. When you look at bands who are 26/27 now, it’s people like The 1975 and Catfish And The Bottlemen, who are still in their youthful phase of getting pissed, taking drugs and shagging groupies. The Manics had left such things behind. Was there a sense of being prematurely old?

“I felt prematurely old at 15, as Philip Larkin said!”, Wire laughs, mirthlessly. “But we’d had a manager dying [Philip Hall, who died of cancer in 1993], a member going missing…”

“At lot had just gone on, unfortunately,” says James. “Obviously, Philip had died. When we were touring Gold Against The Soul I found out my mum had got cancer, and subsequently she passed away in ’99, but she had a long battle against it and that was going on in the background. And Richey’s problems, and then his disappearance, had happened. So it felt like we’d grown up very quickly, in personal ways and also with this very public thing, too."

“But yeah, you’re right", says Wire. "Like you say, we were still really young, but I’d just got married, and bought a little house in Wattsville, and everything had changed. I definitely felt a different kind of responsibility. I felt like the ‘I <3 Hoovering’ T-shirt was a subversive statement. And I think that because of all the shit of 1995, we had no problem dealing with success at all. I can’t lie to you, that year, 1996, was fucking brilliant. And we were invigorated by something. We saw Oasis doing ‘Some Might Say’ on Top Of The Pops in April 1995 and it fucking floored James. He phoned me up and said ‘That’s it!’, then he walked around London for five hours, thinking ‘Why can’t that be us?’”

And exactly a year later, you were supporting them at Maine Road. Did a lightbulb go on over your heads, thinking you wouldn’t mind having a bit of that?

“Yeah, we had no shame about picking up a few of the stragglers of the post-Britpop world! Britpop is presented as being this musically conservative era, but lyrically it just isn’t. There was us, and Massive Attack, and Radiohead at their peak, there were fucking massive themes being put into the Top 10 of the charts.”

I could also mention Jarvis Cocker here.

“Yeah, lyrically you’re spot-on. And Damon at bis best as well. And that just doesn’t occur any more. People can tell me all they fucking want about how great music is, but lyrically there’s a fucking drought. It might be out there, but it’s not in the Top 10, which is what’s important.”

Bands’ work-rates seem to have slowed down drastically since then, as well. “If anyone talks to me now about ‘the treadmill’,” says James, “forget it. Back then, it was ‘GT, boof! Get Gold Against The Soul out, boof! Get The Holy Bible out…’ By 1995 we’d already had three albums out.”

“I do think it’s remarkable that Generation Terrorists to Everything Must Go is only four years,” says Wire. “Like an old-school Sixties band, chucking out an album a year. Our sheer bloody-minded work ethic is a factor. Sometimes it’s meant that over-familiarity has bred a little bit of contempt in people, but it’s the thing that’s kept us just ploughing through all the shit. At the moment, we actually feel like it’s been ages since we released an album, cos it’s been two years since Futurology! And we’re wondering when we can do another.”

And unlike most other bands of your generation – Suede, Pulp, Blur – you’ve never gone on hiatus and come back. You’ve always been around. Even when you announce to the press that you’re taking two years off, it never actually happens: next thing you know, you’re playing a gig in Japan or something.

“There is the feelgood factor we can talk about all the time,” says James, “that we actually enjoy each other’s company. We actually love being in a band. But there’s one other element to it, too. We’re very balanced, in the sense that Nick always thinks about everything, and sometimes I don’t think about it at all. I won’t dissect everything, or say ‘This would be a brave decision’ or ‘We should make it harder on ourselves’. I’m always thinking I want to write a fucking fuck-off amazing piece of music, to match this lyric I’ve been given. I want to write another million-pound dime store guitar riff. I’m always excited about it. Because, I’m not calling myself thick, but I am a bit simpler in the way I approach life.”

I don’t agree, James. You’re underselling yourself. You’re a thinker.

“No, no, but I am very ‘If you enjoy something, fucking do it!’, kinda thing. I never think ‘It’s time for us to go.’ Even at the bottom moments, like Lifeblood or Know Your Enemy, to a certain degree. I still like parts of Lifeblood – I’m not slagging it off completely. But I’ve always got this thing of ‘Yeah, we lost… but, fuck, we can get back on top!’ I have got a bit of a cornier way of thinking about life: ‘Boys, we can do it! We can write the best song ever!’”

This is deliberate misdirection. It suits you to pretend that you’re not the cerebral, intellectual member of the band…

“I’m not! But I’m not! But I’m not!” he cuts in, insistently. “To be intellectual, you’ve gotta think all the time. And you’ve gotta link things up. I don’t link things up. I just have primal urges to carry on. That’s my biggest thing. You can have two bad gigs in a row, and I’ll think ‘The next one’s gonna be great.’ I’ll go onstage thinking ‘Why am I doing this?’ and I’ll come offstage thinking ‘I wanna do it again!’ I have very simple urges: if I think I’m good at something, and I enjoy it, and other people enjoy it, and I’m doing it with two people I grew up with, who I fucking love, why would you stop? I mean, when Jonny Greenwood from Radiohead, who is obviously a genius in his various guises, says ‘I feel as if there’s nothing left for the guitar to do’, well, I do! I feel like going back to learn things off Farewell To Kings by Rush which I don’t know yet! That’s enough for me. I don’t care that I’m copying something else. Because something good comes out of just loving it and being able to do it. I never think ‘Oh, I’m going to learn the theremin instead, because the guitar is over, for me.’ I just think ‘FUCK OFF! Just give me a stack, give me a new guitar, give me a new pedal, give me some lyrics, and I’m good to go.’

EVERYTHING MUST GO, TRACK BY TRACK

ELVIS IMPERSONATOR: BLACKPOOL PIER

JDB: This was very different, to start off with. It’s a prime example of how close you are to a track going in the wrong direction, sometimes. There was this little dining room in House In The Woods, and I remember sitting there and saying to Richey, ‘To me it’s the got the feel of ’12XU’ by Wire.’ [sings, very fast] ‘Saw you in a mag, kissing a man! Saw you in a mag, kissing a man!’ And I sang it to him like that, you know: [sings, equally fast] ’20 foot high on Blackpool promenade/Fake royalty, second-hand sequin facade…’ And even he was a bit like, ‘Hmm, not sure…’ kinda thing. But in my head it stayed like that till we got to the Chateau. And after we’d done ‘Raindrops’ on that first day, Mike said ‘Go through all the songs acoustically for me, please, cos we haven’t got demos for all of them’, So I did it like that: [screams] ‘LIMITED FACEPAINT! AND DYED BLACK QUIFF!’, and he was like ‘There’s a really good song in there, but what you’re doing is fucking awful!’ And I kind of knew it, but I was still stuck in The Holy Bible mindset a bit, with that song. And he said ‘Just play it to me slow’, and I did, and he said ‘It almost feels like an early Seventies Queen song’ I still don’t quite get what he meant by that, but we slowed it down.

There’s something really eerie and unsettling about it, a feeling of unspecified wrongness, before the big chorus kicks in and suddenly you’re home.

JDB: I remember in one of your reviews you said it was, ‘A string of unexpected successive chords strung together.’ And the intro, certainly, is very muso. Those chords shouldn’t go together. And yeah, you’re right. Nick wrote the second half of the song, ‘An American Trilogy in used-up cars and bottled beer’ onwards, but the first part, up to ‘An American Trilogy in Lancashire pottery’, was Richey’s. And as soon as Nick had given me that second verse, it really all came together in my head. But I remember someone saying there is a sort of ‘globalised Reggie Perrin’ vibe to it.”

The lapping of the water at the start causes a feeling of queasiness, particularly given Richey’s last known location [the Severn Bridge].

NW: Totally. We were just trying to create an atmosphere of what we’d been through.

JDB: Yeah. I remember, we did have a bit of a moment about that. But we wanted that sound, because it was ‘Blackpool Pier’. We wanted it to be like how, in the Seventies, people would use sound effects.

Like the sound of the sea on Quadrophenia by The Who?

JDB: Yeah. And especially prog records. But as soon as we put it there, we thought, ‘I hope people don’t think we’re being distasteful here’. But it’s not, because it’s about the lyric in the song. I remember Martin (Hall, manager) and Rob (Stringer, Sony Records) could see we were in a bit of a corner about it and they said ‘Don’t worry. People will know that it’s part of the album because of the lyric.’ Rob was always brave: ‘I don’t fucking care what they say. It’s fucking brilliant! I’ll tell them to fuck off.’ Which is very strange for the head of a record company, you know?

There’s a bit in the Kieran Evans documentary Freed From Memories, which accompanies this reissue, where you say that you were in danger of getting dropped from Sony but Rob Stringer’s vote saved you.

JDB: Yeah. And his quote, which other people have attested since, is ‘Sometimes you’ve just got to give art a chance.’ Me and Nick have this theory that you can’t call yourself an ‘artist’, in music. Sometimes you inadvertently become involved in something that becomes art, but the moment you start calling yourself an ‘artist’, you’re fucked. It’s like when Tony Blair started worrying about his ‘legacy’. You know that you’re gone, and you’ve become too self-important. But Rob actually stood up and said ‘No, fuck off, we’re gonna give art a chance’.

It’s not immediately obvious what ‘Elvis Impersonator’ is driving at, lyrically.

JDB: I was quoted as saying it was about globalisation, but that was a precis-ed version. I didn’t quite say that. I thought it was about the blurring of identity, and everything being post-history.

NW: The atmosphere in the studio when we did it, felt really intense. I remember calling it ‘super-rock’. It is one of our great opening tracks, because it eases you into the new era. And to have a harpist on it, to go from ‘Revol’ to having a harp player, within a year, is quite a leap. I finished off the lyrics, which you can kind of see, in the new box set. I’ve included it. I found this lyric sheet and it’s got ‘Richey: blue, Wire: pink’, cos I’d written in pink! It was pretty much 50/50 in the end. There aren’t many lines to it. It’s like a haiku, what Richey wrote. And it felt nice in a way, co-writing with Richey again, in the sense that I was finishing it off. Then crash-bang into ‘A Design For Life’.

A DESIGN FOR LIFE

JDB: It’s obvious what that’s about. ‘A Design For Life’ is still the best lyric that describes working class emotions and ambitions.

Was there an element of having it both ways? Just as Springsteen must have known that many people would chant ‘Born In The USA’ unironically, you must have been aware that some people would be bellowing “We only wanna get drunk” without the implied inverted commas.

JDB: Good analogy! I like that. But yeah, yeah! Fuck it. I don’t give a fuck, either. If it helped people to enjoy a gig, to go ‘We only wanna get drunk’, and then get drunk, I couldn’t give a fuck. [He’s emphatic and animated on this point.] I couldn’t give a flying fuck. [Adopts voice of prissy, stuck-up critic] ‘Oh, how irresponsible, oh how disingenuous, blah blah’ – oh, fuck off, you fucking prick. I’m not that precious about it, I’m really not. If it helps you get where you want to go, in a gig, great. It’s such a brilliant lyric, ‘We don’t talk about love. We only want to get drunk,’ and then the lines after that are just genius: ‘And we are not allowed to spend/As we are told that this is the end.’ You know? That’s a fucking amazing couplet, that is. Foretelling the fear of boom-and-bust politics, and ‘tighten your belts’ and all that. Being told ‘stay in your place’, but also ‘you can’t enjoy yourself either’.

NW: Undoubtedly you’re right, but there’s also part of me that loves the fact that our culture loves to get fucked out of its mind and go insane. Because that’s what makes football matches and gigs exciting, isn’t it? So there was that duality. And obviously, it was a reaction to the arch raised eyebrow of bands like Pulp. That was my only problem with Pulp: it always seemed to be done with such a sense of irony, and everything was presented as some sort of Carry On film, which was anathema to me. The humour in the Valleys is absolutely vicious pisstaking. But it’s never that arch, ironic raising of the eyebrow. It’s just fucking verging on violence. So, everything was turned into a greyhound race, and I just didn’t get it. I was getting angrier by the minute. And I had rediscovered what I liked about where I live.”

Everyone talks about the inscription above a library which inspired the first line, “Libraries gave us power”. You don’t hear so much about the second line being inspired by Auschwitz.

NW: ‘Work made us free’ is ‘Arbeit Macht Frei’, yeah.

JDB: I never thought that was intentional, at all. Because I always took it in the positive sense. There’s always a chance I’m gonna misread things. Because I always try to check stuff, especially on The Holy Bible with Richey, so I know what I’m singing about, but you don’t ask about every line. And for me, that was specifically about South Wales, and our experience, but it could have been about Yorkshire as well, or wherever. It’s about a certain community finding something that fits them, and that gives them pride. And South Wales was like the Klondike: yes it was hard, yes it was tough, but as a result of all that, it shaped an identity and gave people pride. And in the end, miners were some of the best-paid workers in Britain.

Is it too Hollywood to speak of one song saving a band?

JDB: No no, it’s completely true. I think if we hadn’t had the impact of ‘A Design For Life’, we might have crawled on to one more album, and that would have been it.

NW: No it’s not. Tracks like ‘No Surface’ and ‘Kevin Carter’, I love them to bits, but they might never have even been recorded if it wasn’t for ‘A Design For Life’. It’s that crucial. Because for five months we didn’t do anything. I didn’t even want to send any lyrics to James, but he was badgering me, post seeing Noel on Top Of The Pops, with his raised guitar. Then I sent him ten sheets of paper with two poems on, basically, and he picked the ten best lines off it. It could have been a good album anyway, without that song, but it’s such a statement, I think, musically as well. It’s just one of those records that jolts you, the minute you hear it. Even when James sang it down the phone to me. And when Sean added that time signature, the waltz, it just hadn’t been in rock music. Not that I can remember, anyway. So when he played it down the phone, I just knew that it would have been wrong not to record that, and we had to continue.”

KEVIN CARTER

JDB: That lyric, for Richey, is very concise, actually.

And again, like ‘Elvis Impersonator’, there’s something really unsettling going on. The line “The elephant is so ugly/He sleeps his head, machetes his bed” gives me shivers.

JDB: It is. It’s the song of a haunting which results in suicide, essentially. It’s an awfully tragic lyric. It’s beyond belief.

NW: It’s unbelievably jarring, the lyric. For that to get in the Top 10, and with the band kind of doing a salsa thing, with the drummer playing a trumpet, was amazing. And I don’t really know which side Richey’s lyric is on: is he accusing the photographer of exploitation, or praising him for showing a truth we’re all scared of? There is a sense of disquiet. The lyrical themes don’t differ a lot from our lineage. Perhaps the actual words are less harsh.

ENOLA/ALONE

JDB: I was saying earlier: ‘daffy’. ‘Daffy’ is one word you used to describe the lyric.

Did I?! I’ve got no memory of that whatsoever, and no idea what I would have meant anyway.

JDB: Yeah, you did.

Note: I’ve since checked my MSP biography, Everything (A Book About Manic Street Preachers), and I definitely didn’t use it in there. If anyone can provide evidence that I used it elsewhere, I’ll swallow my words, but for now, I’m sticking to a hardline denial that I ever called it ‘daffy’. It’s one of my favourite-ever Manics songs.

JDB: It’s cool, don’t worry about it… But it’s amazing how on Generation Terrorists, Gold Against The Soul and The Holy Bible – and I’m talking about lyrics here, nothing else – there are certain things that are confrontational, or dogmatic, or didactic, whether it’s written in the first, second or third person, but we were never really emotionally open. Richey was, absolutely pouring forth emotionally, but it was kind of disguised one step removed so you could never quite tell, at the time. Obviously we’ve all figured it out now. But with Nick, if you take a lyric like ‘Enola/Alone’ or ‘Everything Must Go’ or ‘No Surface All Feeling’ or ‘Further Away’, you know, for someone who’s so fucking spiky and so confrontational, for him to be that emotionally available and open is a massive leap.

He is someone who keeps his guard up, right down to the sunglasses.

JDB: He is, yeah. But lyrically he poured forth. So we’d broken free from that identity that we’d created for ourselves, and everything became a bit more human. And lyrically it still sets itself apart, whether it’s about Willem De Kooning’s Alzheimer’s or the haunting of Kevin Carter.

NW: It’s one of my favourites on the album. I absolutely adore it. ‘Enola/Alone’ was written purely in France. I remember being in my room in the evening, looking at a picture from my wedding, which had Philip in it, and Richey, which was only two years previous. And both of them were gone. So it did come in a rush, and we wrote and recorded it in two days.

It’s a song based on imagery, so it’s not totally literal, but it’s just based on that feeling of loss, looking at old photographs. It’s a well-worn Manics trait since then, I guess. It’s pure naturalism. I didn’t realise how open I was, with my emotions. We’d never really been like that before. It was always allegorical. I think the key line is ‘All I wanna do is live, no matter how miserable it is.’ That absolutely summed up everything I was, at the time. I didn’t leave the house for five months, in South Wales, apart from walking the dog.

JDB: ‘Enola/Alone’, I can’t deny, wouldn’t sound the way it does without the first Oasis album. It just wouldn’t.

EVERYTHING MUST GO

JDB: It’s very personal for us, and a cathartic moment. It’s a plea to our fanbase, and when bands talk to their fans – like The Who used to, to a certain degree – it’s an art form in itself. It’s quite a tricky thing to do.

It’s such a Manics thing to be that self-aware: to hear the voice of your fans on your shoulder, and pre-empt them by getting your justifications in first.

NW: The amazing thing about that is that we weren’t even doing it in response to Twitter or whatever, because that wasn’t even there. There was just the fanzines and the letters pages in Melody Maker and the NME. But with ‘Everything Must Go’, I was supremely aware of how everything was gonna turn, because it was quite late in the songwriting process. I knew we had all these other songs, and how they were, sonically. And I’d written a load of absolutely garbage lyrics in the time after Richey disappeared, half-arsed attempts, chasing my tail. It was all shit, and I was painting and taking pictures and it was all a load of rubbish, but obviously it was for some purpose, which was for me to de-clutter and come out with something more direct, like this.

Sonically, the title track is possibly the most extreme case of the album’s clattering, turbo-charged Spector sound.

NW: It’s become over-familiar, for us, because we play it so much. But even for me, when I play it on the record, you can hear how fucked up it is. You can hardly hear the vocal, cos everything else is so loud. James had been massively influenced by McAlmont & Butler’s ‘Yes’, which Mike had done. I was just annoyed with them cos they’d nicked my title – my contribution to our song ‘Yes’ on The Holy Bible was just the title, and nothing else!

SMALL BLACK FLOWERS THAT GROW IN THE SKY

JDB: ‘Small Black Flowers’ talks for itself. It’s holding a mirror up to yourself, like John Gray the philosopher, in Straw Dogs: Thoughts On Humans And Other Animals, saying we’re so arrogant to assume that we’re so much better than the animal world. That was definitely a moment, when we got that lyric. And it scanned, which… I’m not being rude to Richey, I’m really not, but his lyrics would often be off-kilter and wouldn’t scan, and I’d have to make it fit. And that was fine, because something good would come from that. I’d have to stretch, and it would lead to a different time signature or something. And the words were always just brilliant, but sometimes he was a bit more freeform. But I remember when he gave me ‘Small Black Flowers’, which was originally called ‘Stalemates’, I think. And it scanned! Boof, boof, boof. And it’s really strange but it reminded me of a book I’d read, called The Woman In The Dunes, by a Japanese author called Kōbō Abe. It’s about a woman who gets trapped in the sand dunes by people from a village who want to use her as a breeding agent. Spooky book. So I remember linking that in. And he told me about another reference, this zoological research document he’d read about how monkeys, apes, I think it was chimpanzees actually, can start seeing hallucinations. And I loved the lyric so much, and I remember thinking ‘Oh fuck, I’ve got to do something great with this.’ And I thought ‘It can’t be a band song.’ It had to be an acoustic song. I’d been listening to an old Rolling Stones song called ‘The Spider And The Fly’, and I modelled it around that: not musically, but just the feel of it. So that was the gestation of it.

It’s one of Richey’s greatest-ever lyrics.

NW: It is. Sometimes you get fans moaning about James editing Richey’s lyrics, like he did on Journal For Plague Lovers, but it always fucking happened! Even when he was around! Firstly, me and Richey would edit ourselves, then James and Sean would edit, then James would edit. It’s such a crucial part of Manic Street Preachers, the editing process. I’ve no idea why people get annoyed by that. It fucking drives me insane. Take ‘A Design For Life’! It was fucking ten pages long, and it ends up ten lines!

So in a way, James is a ‘writer’ of the lyrics, because that kind of editing constitutes a form of authorship.

NW: It does. Some of the words, sometimes, like ‘William’s Last Words’ [Journal For Plague Lovers track], which I actually wrote the music to, was three pages long, of typed A4! You have to cut it down, otherwise you’d just have to release it as a piece of prose.

Going off-topic, Journal For Plague Lovers (essentially The Holy Bible Part 2, on which the Manics adapted the unused lyrics Richey left behind) still doesn’t get enough love. It’s one of the finest Manics albums.

NW: “I like to think we did the fucking best that anyone could do, with it. We struggle to play any of the songs off it live. It’s not that we don’t like it. In fact, Sean loves that record, because he did the drums in two days and Steve Albini let him go, ‘Yep, you’re done!’

THE GIRL WHO WANTED TO BE GOD

NW: We were obsessed with ‘Dancing Queen’ by ABBA, so it’s that mixed with Sylvia Plath, which is where Richey nicked the title from. That da-da-da-da-da strings thing, which is in ‘Motorcycle Emptiness’ as well, we got from ABBA. We did a version with Stephen Hague, because we thought we’d like a version that was like ‘Regret’ by New Order, really shiny and poppy, but it just didn’t work. It was a bad fucking session in every way. It was in Real World, and it was like living in Brian Pern’s head. And everything had coriander and dill in it. It’s everything I hate about life, you know? Communal dinners with other bands… ugh! So it didn’t work out, and we redid it with Mike. We used a bit of the drums and the bassline. It’s quite a nimble bassline, actually. It’s such a glorious pop moment. Lyrically, again, I ended up writing half of it, like ‘Elvis Impersonator’, which I think really works. Some of our best lyrics are when me and Richey have traded lines. So I had no problem with that.

JDB: Yeah, it’s got that diddle-iddle-iddle thing going on, the same as ‘Motorcycle’, and I remember feeling uncomfortable about that. I knew where the reference ‘The Girl Who Wanted To Be God’ came from – Sylvia Plath – and I remember thinking, is it a bit frivolous? To turn it into Manics at the ABBA disco? But when I sat down, that’s what came out, straight away. And there’s a tiny bit of Love Unlimited in there, as well. Because I remember I was going down to the original Heavenly Social on Great Portland St, and the Chemical Brothers would always play ‘Under The Influence Of Love’ towards the end of their DJ set. And it’s such an amazing record. All I’d heard by Love Unlimited and the Love Unlimited Orchestra before that was ‘Walking In The Rain With The One I Love’. My mum had that record. But there’s an assuredness to ‘Under The Influence Of Love’, that production by Barry White. When I saw the lyrics, I heard the chords straight away in my head, and I remember thinking ‘If I could just get a bit of Love Unlimited Orchestra in there…’ Although in the end, we didn’t really. But the initial direction was definitely dancey in that way.

REMOVABLES

JDB: Let’s not even go there, with what that lyric’s about…

OK, then I will. It’s about impermanence and mortality, and in many ways is Richey foreshadowing the spirit of Everything Must Go in his own bleak way. And the reference to bronze moths dying easily is likely to be derived from Tennessee Williams’ Lament For The Moths (“A plague has stricken the moths, the moths are dying/Their bodies are flakes of bronze on the carpet lying…” ), of which the Manics were on the record as being admirers. Of all the songs on Everything Must Go, it’s the one which would have slotted seamlessly onto The Holy Bible.

NW: Yeah, even musically, it’s got that sort of Nirvana MTV Unplugged sadness to it. It’s brilliant live, actually. I love playing it live. That chorus, emotionally, gets me. Those lines, ‘All removables, all transitory’, there’s something about it that I find quite chilling. It kind of sticks out a bit, on Everything Must Go, but I don’t mind that at all.

And then you follow it with ‘Australia’, which is the opposite extreme.

NW: Yin and yang!

AUSTRALIA

NW: I remember my body was absolutely fucking frozen. I was not well at all. Ever since we went to Thailand in 1994. I weighed nothing, I was very unhealthy. I had this liver condition, that I’ve still got, and I turned yellow. It was a horrible time.

So the bit in ‘Australia’ about “My cheeks are turning yellow, I think I’ll take another pill” is literal?

NW: Yeah, it’s totally true.

And “praying for the wave to come now”, a ready-for-drowning thing?

NW: Yeah, it’s Stevie Smith, Not Waving But Drowning, and all those poetic notions. But again, I did purposely try to rein myself in. It was a much longer lyric. Famously, it was my ‘Life On Mars?’, and me trying to run away. I did only get as far as Torquay, for a long weekend, but it did its job for me. It was in Agatha Christie’s hotel, actually. Which inspired me to write.

You’d always wanted to write a song to get played underneath the football highlights on the TV, and this was it.

NW: I have to give a nod to Dave Eringa, because we’d done it with Mike and even though it was all there, the mixing was terrible and it wasn’t working, and Dave really made it even shinier and even more Goal Of The Month. He did an amazing mix on it. It actually was a semi-hit in Australia, and the Australian tourist board used it…

INTERIORS (SONG FOR WILLEM DE KOONING)

NW: It’s the only one that’s quite hard to play. The bassline doesn’t hang together as easily as some other songs.

The bassline has a definite hint of ‘Nothing Can Stop Us’ by Saint Etienne.

NW: It really has, and I meant to say it the other night [at the Royal Albert Hall]d and give a shout-out to Saint Etienne, because we loved that record. I remember that glorious little Heavenly period of us releasing ‘Motown Junk’, and Saint Etienne releasing ‘Nothing Can Stop Us’, and Flowered Up releasing ‘It’s On’.

JDB: Yeah, I’ve admitted that before. ‘Nothing Can Stop Us’ is probably one of the greatest records of the Nineties, absolutely amazing, so there was a shape, in there, from that. There was definitely an echo. And to actually try to write on behalf of someone else is hard. It’s a very humane lyric by Nick.

NW: Again, the lyric is quite jarring, about an at the time fairly obscure American abstract expressionist having Alzheimer’s and not knowing what he was painting. I really buried myself in art. That’s one thing that came out of that period when Richey went away, was discovering visual art. And rediscovering RS Thomas, and social history, which all fed into This Is My Truth Tell Me Yours as well.

FURTHER AWAY

JDB: It was a very shocking lyric, for Nick to give to me.

Especially after the legendary interview on Snub TV in 1991 where Nick said “We’ll never write a love song ever. Full stop. We’ll be dead before we have to do that, anyway.”

NW: It’s probably the only one! It’s a bit of a throwaway lyric. It was written on the Suede tour of Europe, with The Holy Bible, and I was miserable beyond belief. Not because of anything to do with Suede, but Richey had come out of rehab, and nothing added up. We were playing a record that no-one was buying, James was just pissed all the time, Richey was chain-smoking 40 fags a day on the bus…

I bet you didn’t like that.

NW: No. Everything was just an apex of shit. I’d been married and I wanted to be at home, I saw no purpose in doing what we were doing at all, and it was just horrible. I was not a good traveller, I didn’t eat anything, I didn’t do anything, I just moaned. And I did give the lyric to James, and told him I wanted to fuck off home, but he was way too hungover to take anything in, at the time. But he did eventually come up with something great, as is his wont. It just is a really fucking great Oasis song, basically. The minute he played it to me, I thought it could be on Definitely Maybe.

JDB: I remember thinking ‘No, don’t reach for any tricks, just use chords, it’s a pure lyric, it’s a breaking-the-rules lyric for us, so just be upfront and pure about it.’ And I remember halfway through recording it, I just had this weird urge to start playing the guitar like Bernard Butler. Sometimes, when you’re writing something, you’re not bored but you sort of reach for things like ‘I wonder what he would do. I wonder what John McGeoch would do. I wonder what Bernard Butler would do.’ So there are echoes of Bernard Butler’s playing in there, which I’m not afraid to admit. I’ll namecheck Oasis, peers-wise, and Bernard Butler, but other musicians are really scared to do that. I think good things come out of listening to other people’s music and just trying to imagine what they would do, sometimes.

NO SURFACE ALL FEELING

JDB: It’s really strange doing this song live, every night, when you get to the line ‘What’s the point in always looking back, when all you see is more and more junk?’, and you can see people’s faces, like [Nelson Muntz laugh] ‘Ha-haa, gotcha!’

NW: You look at the front row and they’re almost laughing, ‘That’s exactly what you’re doing!’

So, this song had already been knocking around, in Richey’s time?

NW: I remember we were doing this fucking gigantic Carnival Against The Nazis thing in Brockwell Park in South London, and it was fucking massive, we had no idea what we were doing at that point, we were out of our minds, we were really disconnected. I think ‘Faster’ had just come out, because we were in Holy Bible gear, and there was that haunting picture of Richey with bars that make it look like he’s in prison. And we had a rehearsal on this fucking industrial estate in South London. And we did ‘No Surface All Feeling’. And I thought ‘Fuck me, that really sounds like a Smashing Pumpkins song, with our take on it.’ And I’d written all the lyrics. So the lyric is nothing to do with what happened post-Richey’s disappearance at all, because it was already written when he was around. But I was quite blown away by it, because it had that classic quiet/loud Pixies ethos. So, all the songs that were fully-formed, written by me and by Richey, perhaps never would have made it if it wasn’t for ‘A Design For Life’.

MR CARBOHYDRATE

Not an album track, but if we can discuss one B-side, it needs to be this. Nicky Wire’s personal manifesto, his ‘Faster’: a proud proclamation of his determinedly anti-rock & roll lifestyle. (“They call me a boring fuckhead/They say I might as well work in a bank/I tell them I wish I was…”)

NW: Well, it should have been on the album. I wanted it on the album. At the time, that is me: I Love Hoovering, domestic bliss, watching the TV, reading poetry. I mean, I love the feel of it. There were actually a lot of good B-sides at that point: ‘Dead Trees And Traffic Islands’, ‘Horses Under Starlight’ with Sean on trumpet again, the Burt Bacharach thing in that is gorgeous. There’s a sense of freedom in all those singles and the B-sides that perhaps the claustrophobia of The Holy Bible wouldn’t allow. Then again, it’s so hard to predict, because there’s no fucking connection between Generation Terrorists and The Holy Bible, musically. No drum patterns in common, nothing. Sometimes people say the early stuff is similar, but ‘You Love Us’ wouldn’t have fit on The Holy Bible. It’s just our imaginations, really: the minute your imagination goes, it’s over. If we didn’t have imaginations, we couldn’t have done Futurology.

“I look to the future, it makes me cry/But it seems too real to tell you why…”

The Manics have now done two classic album tours in succession. Surely they can’t keep doing that indefinitely.

“We have,”, says James, “and there is a quote from Nick flying around, saying that if you do too much of that, you turn into a museum. I suppose the reason we’ve done two on the bounce is that we released two new albums (Rewind The Film and Futurology) in the space of a year. So we’ve definitely earmarked time to go away and start a new record. We’re in that headspace now.”

Is there new material already?

“There’s not much happening yet,” says Wire. “There’s just not. I’ve got loads of words, but thematically they’re just not hanging together. James has played me one track that does sound great, which is called ‘Holding Patterns’, but other than that, this was meant to be our summer off. Also, we’ve lost our studio in Cardiff, due to the urban crawl. It’s going to be demolished in September. And there’s nowhere else left. It’s like Will Self’s thing about the doughnut, where it used to be that all the creative people and squatters were in the centre of cities, and then they became suburban cos they couldn’t afford it. So we don’t have an HQ any more, which is kind of emotionally scary and demoralising, because it’s been such an amazing place for us for the last 15 years. So we’re trying to find a house somewhere that we can build another studio. So we are in a state of flux, and I’m glad we’re doing this tour because it gives us breathing space.”

Futurology is widely and correctly considered to be one of your best albums, so the tank can’t be running dry.

“I do love Futurology”, says James. “I was listening to it, only the other day, to get a bit of a reference for where we’re going next. And what I think people missed out on, when they were reviewing that, was that Nick reached a bit of a peak on that record. He wrote all of ‘Futurology’ the song, music and lyrics, he wrote all of ‘Divine Youth’, ‘Mayakovsky’ was all his, and one other track, I can’t remember which. Undeniably we’ve got to get out of the loop of doing the classic albums now. But there are not as many rules around now, are there?”

What do you mean?

“Well, when you were faced down with the editors of the NME and Melody Maker and Select, you’d realise that sometimes subconsciously, you’d been thinking ‘What would they give us a kicking for?’ And there’s no-one there to give you a kicking now, apart from this spurious ether of unedited judgement. And at our stage, the only thing you’ve got to do is come up with the best song you’ve ever written, which is enough in itself. And it’s hard enough for Nick to write a lyric that’s going to stand alone, and be about something other than just ourselves. To try and mirror something, or to try and report something, or to try and microcosmically solve something, in your head. That’s enough of a challenge in itself. So everything has become simpler, in the sense that if you can just prove that you can still do it, better than anybody else and nobody else fills that gap, then you’re still Game On.”

James is that rare thing: a musician who can actually see the value of a critic.

“It’s not a question you asked, but I do think music has suffered from not having that scrutiny of a music press. And sometimes it was blood-curdling, sometimes it was unreasonable, sometimes it was hypocritical, sometimes it was unwarranted. But it kept you on your toes. And unfortunately, the environment you’ve got now is what this generation wants. They don’t want the scrutiny of criticism. We’ve come full circle: you’d have laughed, back in the day, if someone like Gary Numan said ‘Oh, critics are just jealous because they can’t do music’, but that’s what we’re faced with now, lots of people in bands saying ‘Who are you to judge me?’ Bands have it so easy now. We’d get absolutely killed for doing, like, two festivals in one summer. If we did Reading, and Glastonbury, and T In The Park, you’d get ‘You money-grabbing, so-called working class bastards!’ You’d get a kicking for it. But now, you get American acts coming in and they’ll do fucking Wireless, they’ll do V, they’ll do Reading, they’ll do fucking everything! There is no scrutiny at all. Jack White is the indie paragon, trend setter of indie style, and he’s a Coca-Cola boy. Kurt Vile, who I love, gave his music to Bank Of America. There’s no scrutiny, nothing. And we’re worse off for it.”

The headline-grabbing, ticket-shifting nostalgia tours mask the fact that the Manics have been on a creative roll for the last ten years.

“Send Away The Tigers, hardcore fans don’t like it,” says Wire, “but normal people do. If it wasn’t for Send Away The Tigers, we wouldn’t be here.”

A ‘home win’, as you called it at the time.

“Yeah. And since that moment, it’s been a pretty amazing decade, really. Whether it’s Journal For Plague Lovers for some, Postcards From A Young Man for me, which I just adore, and Futurology, undoubtedly, is up there in perhaps our top three records. And to pull that off again, in a way, is why we’re dithering. Because if the next thing isn’t as good as Futurology, we don’t wanna do it. We don’t want to end – if there is an end – on a low. It has to be on a fucking high.”

Everything Must Go, the 20th Anniversary Deluxe Box Set, is out now. Manic Street Preachers play the Eden Project in Cornwall on July 9, Truck Festival in Oxfordshire on July 16, and Victorious Festival in Portsmouth on August 27