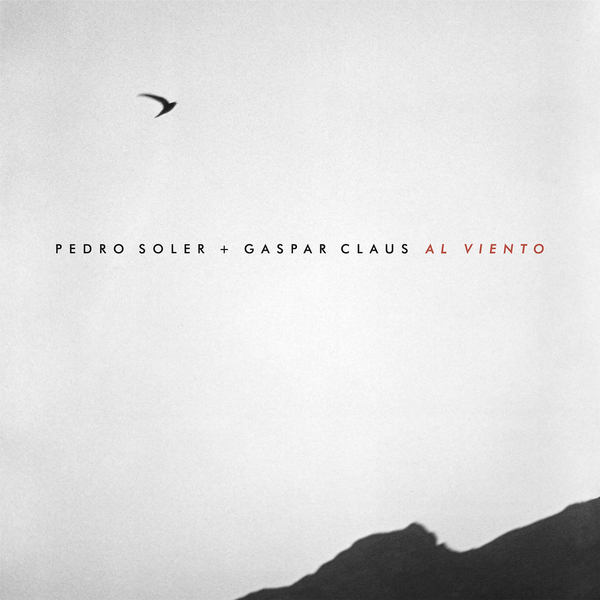

Al Viento, or "to the wind" in Spanish, is an enigmatic title that deliberately conjures up feelings of transience, and might make you – even if fleetingly – consider your own mortality. Certainly the passing of time is never far from anyone’s thoughts given the intergenerational set up here. This largely instrumental album from Pedro Soler and Gaspar Claus is their second, following 2011’s acclaimed Barlande. Soler, the father, is a celebrated French flamenco guitarist born in 1938; his son Claus – born in 1983 – is an in-demand cellist who studied at the Perpignan Conservatoire and is now involved in avant garde and improvised scenes in his native France, as well as Tokyo and New York.

Al Viento is no great departure from Barlande, it just feels fuller, more developed, richer. Opener ‘Cuerdas Al Viento’ is an ambitious eight minute meditation that transmogrifies a number of times before the conclusion, pulling together refashioned flamenco structures with experimental scrapes and drones, the old with the new. The consolidation of styles is thankfully seamless, undertaken by great musical clinicians with a tenderness and attention to detail that allows these sounds to constantly segue and evolve into something new. There’s light and shade too in this tour-de-force opener; Soler begins breezily like a summer’s morning, Claus injects plenty of melancholy.

‘Vendaval’ is a more traditional offering, but Soler the Frenchman, perhaps having not grown up an Andalucian, is no flamenco purist; he’s not afraid to purloin other styles such as Eastern European folk or classical whenever the mood takes him either (Claus also mimics classical chamber music on the rather stately sounding ‘Rocío Y Corrales’).

At the other end of the scale, ‘Silencio Ondulado’ – the only track with vocals on – sounds like Leonard Cohen with distressed drones and atmospheric bowing superimposed, building to a frightening crescendo following plenty of tension. Aided and abetted by his son, Soler ventures into unchartered territories, exploring sonority unabashed in a way few artists his age – bar perhaps Yoko Ono – are willing to venture. It’s a fine balance to maintain, but Soler’s years of experience and Claus’ immersion in the experimental somehow compliment each other.

On ‘Corazon de Plata’, where Soler plays the most languid of guitar parts, Gaspar takes the opportunity to unleash ferocious stabs of noise reminiscent of John Cale’s strokes on ‘Venus in Furs’. It’s perhaps surprising that it works, and yet it somehow does; whether the familial connection contributes to this cognitively dissonant fluidity is anyone’s guess. If the title makes one think about death, then the album itself makes one think about life, and how precious our human connections are, particularly between a parent and their offspring. Al Viento demonstrates what a beautiful bond that can ultimately be, and reminds you to cherish it if you still can.