“Juarez is like a haunting for me,” Terry Allen says when I ask him how it feels to look back at his debut, forty-five years later. “It’s made itself into many manifestations, including sculpture, theatre, movie scripts, writings… and I imagine it’s still lurking somewhere waiting to raise it’s head again. In one way or another it’s probably informed everything I’ve made.”

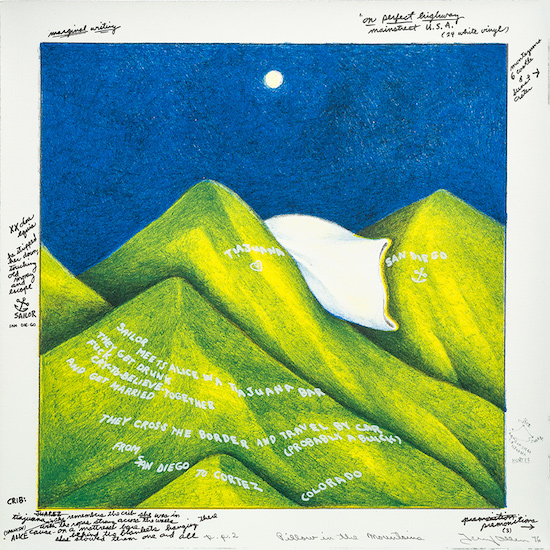

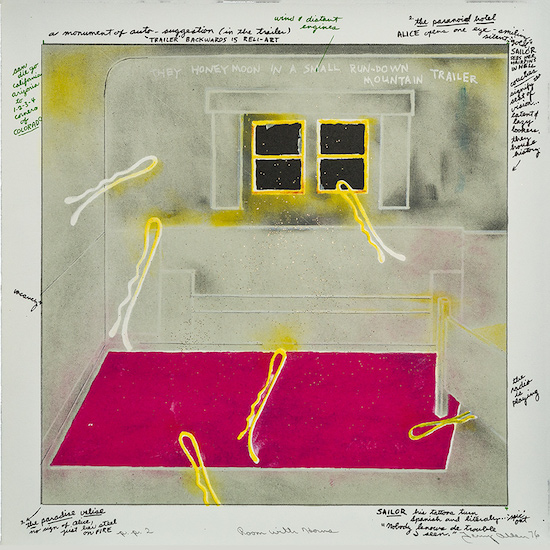

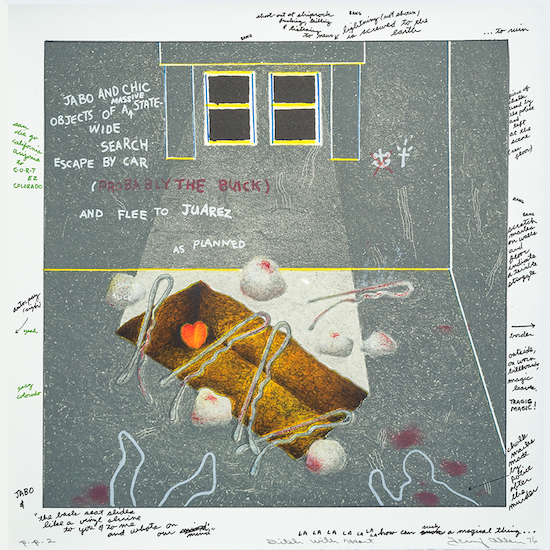

Juarez was never just an album. It’s lurid visuals and lucid poetry emerged simultaneously as an entire mythos, like something that fell out of a dream. “I was working on a body of visual pieces and songs that were moving toward the same place and eventually became Juarez,” Allen explains. “I did a slide presentation and played some of the music along with it. Jack Lemon, who owned Landfall Press in Chicago, saw the presentation and asked me if I’d like to do a suite of prints and a record album. I said yes.”

The matter-of-factness with which he explains the origins of this peculiarly multivalent work belie the singularity of the work itself. If, today, Allen is well-known and regarded as a songwriter and performer of his own tunes, a collaborator with David Byrne whose songs were covered by Little Feat and Robert Early Keen, this is almost entirely an aspect of the world opened up by Juarez itself.

A graduate of the Chouinard Art Institute of Los Angeles, he had already exhibited prolifically since his first solo shows at LA’s Gallery 66, Michael Walls Gallery, and Pasadena Art Gallery in the late 60s. So it makes no more sense to regard the visual aspect of Juarez as mere illustrations of the songs than it does to see the songs as sonifications of the images. It was a question, as he puts it, of “creating two very distinct aspects of the same idea.”

“The first Juarez drawing was called ‘The Juarez Device’,” Allen explains. “It was based on a hog-killing machine that I found in a book called Mechanization Takes Command. It showed these hogs on scaffolding, how hooks went around their feet and turned ‘em upside down and then their throats were cut. I changed the drawings so they began to be kind of people-hogs, then when they turned upside down, they became like rocks or trees or bushes – they became natural elements. I just called it ‘The Juarez Device’ – I don’t know particularly why.

“That drawing was done in L.A,” he continues, “Then we moved for about five months back to Lubbock, and I had a studio, which is where I did the drawings ‘Cortez Sail’, ‘Dogwood’, and ‘Border Palace’ – the first three drawings in the series, which were kind of a triptych at the time. I wrote the song ‘Cortez Sail’ in Lubbock, and I think I started writing ‘Dogwood’ there, and then I got a teaching job at Berkeley. I started making a lot more Juarez drawings, and I wrote a lot of those songs there in the practice room at the university.

“They kind of came and they just kind of evolved. A lot of it I can’t remember exactly what the order was.”

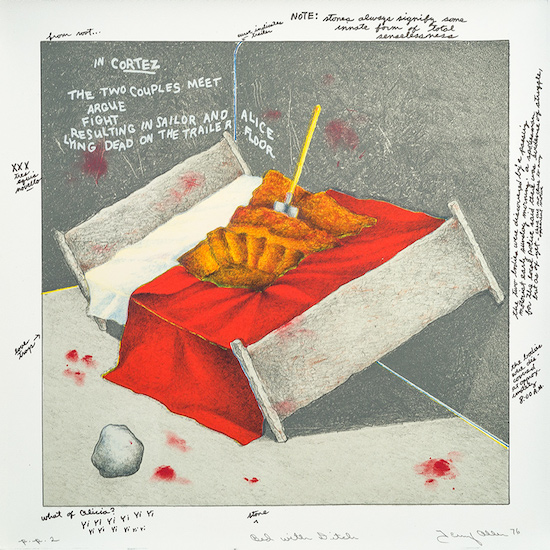

The images themselves were created using lithography, a method of printing from an etched limestone (or later aluminium) plate. “I like drawing on stone,” Allen told me when I asked him about this method. “How it feels. Limestone seems alive. Drawing on an aluminium plate is like kissing a dead person.”

The inseparability of image and sound to this project is evinced somewhat by its immediate predecessor, a series from 1968 called The Cowboy and the Stranger for which Allen glued a box on the back of the pictures frames to contain a tape of the related song. Similarly, Juarez itself was first shown in an art context, at the Houston Contemporary Art Museum in 1975. “All of the drawings was hung in order in one big room, and then the music played with slides in another room,” Allen explains. “I did a lot of these slide and music presentations while I was working on Juarez. I would play recordings of the songs, or in some cases play live, while the slideshow was going of the images.”

“That’s what Jack Lemon from Landfall Press saw; I was in Normal, Illinois doing a presentation for the school there. He came and he asked me if I wanted to do some prints and maybe do a record. So that’s how the album, and the prints, really came about as far as a tangible thing.” In this regard it makes more sense to see the whole Juarez project as a kind of conceptual art project with two sides, rather than a simple record album with some nice artwork. Think of Cory Arcangel’s records with Title TK, more than the switchable cover sleeves to Pulp’s Different Class.

“Crossing these different worlds of music and art has been interesting,” Allen says. “There was a definite collision between dealing with people in the art world, that kind of mandatory snootiness that you encounter periodically, and my music. It was always like, ‘Why do you do this country music?’ Then you’d get the same thing with some record people – not so much the artists or musicians, who were curious, or could care less if you were working on a show for a gallery or a show in a club. But there was kind of a double edge, and I learned to live with it.”

“I think that was one of the reasons David Byrne and I became close,” he continues, “He has encountered that same duality endlessly. That collision between media, cultural ideas of what a song is, or what a painting is, what a play is, etc. I think it’s always been exciting to me, to challenge and push the idea of what something is and can be.”

Terry Allen’s Juarez is released by Paradise of Bachelors on 20 May