Thalma Goldman (Cohen) was brought up by Zionist parents in Rishon-le-Zion, Israel. She arrived in London in the 1960s and soon contributed to its cosmopolitan atmosphere. She happily mingled with anyone she met, whether homeless person on the street, born Londoner or rabbi. Her openness to different influences seems to be a family trait: her father had a great love for Billy Bunter books and public school humour, acquired, we suspect, from the British when they were in Palestine.

However, there is little evidence that Thalma ever compromised to fit in, and her art has been controversial. Moreover, she rarely suppresses her thoughts before she utters them, but this has not been a deterrent to making friends. This book is a tribute to her artistic talents put together by some of her close friends. It is not an exercise in art criticism but an attempt to give an insight into what it means to express her unique vision in the way that she does in many different aspects of her life. Much, of course, has been left out. We have focused our attention on her animations films, her collaborators, and on some of her recent paintings and drawings.

Thalma does not reflect in an obvious way on the sources of her own work, nor does she analyse its significance in cultural, political, or artistic terms. Her films, in particular, certainly had an impact at the time, and her recent drawings in betting shops are a sharp comment on a significant part of contemporary life. We are fortunate to have the observations of Annabel Jankel, a film maker, who knows Thalma and who contributed greatly to cultural life in the UK when Thalma was in her most productive period.

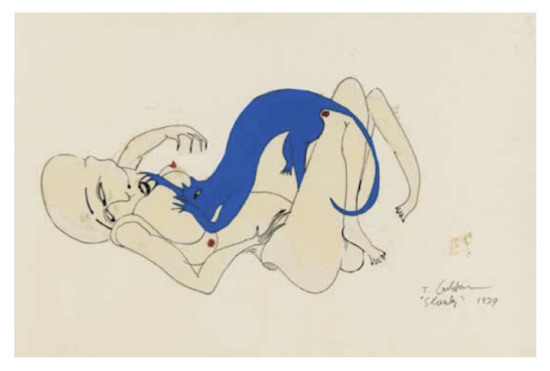

After studying at St Martins School of Art and the London Film School, Thalma made three animation films that achieved success and notoriety. Amateur Night appeared in 1975, Night Call in 1977, and Stanley in 1979. The films were shown at international festivals, and Stanley was an official British entry for the Berlin Film Festival of 1980. It was shown at the time along with Amateur Night in the BBC arts programme, Arena.

Thalma began another animation film after this but it was never finished. Hand-drawn animation, so demanding, time-consuming, and costly, was beginning to be replaced by newer methods and by computer generated images. Thalma sees herself primarily as an artist, especially in the tradition of the finely-drawn line. This book is an opportunity to display some of this work which has rarely been seen in public exhibitions.

Public reaction to Thalma’s work is striking in the sense that it is often extreme, yet seems to express polar opposite attitudes; that her work is feminist, anti-feminist, charming, charmless, crude, exquisite. Men and women may respond differently but gender is too simple a category to adopt here. The excerpts from newspapers and magazines reproduced do, of course, reflect the social attitudes and movements of the 1970s and 80s. Thalma was described as a ‘girl’ or ‘pretty girl’ before her achievements were mentioned. However, sexism has by no means gone away since then. In the recent archives of the Melbourne International Film Festival (at which her films were shown in 1976 and 1980) Stanley is described as “The adventures of an erotic cat”. Besides a failure to observe any subtlety in the message of the film, the reaction could be that of a sex-starved male from the Australian outback, eventually making the journey into town for some recreation.

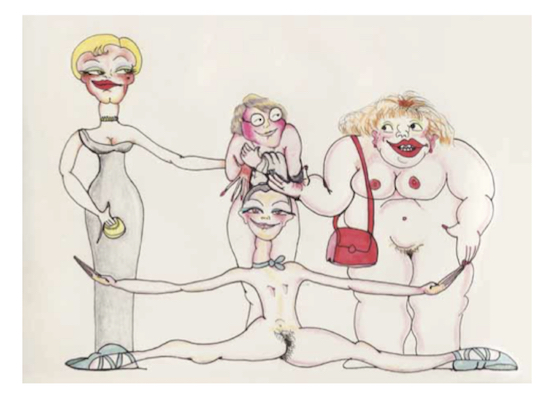

One critic in the 70s thought that the striptease setting of Amateur Night was a comment on the anti-cultural attitude of the British working class, forgetting that striptease was not confined to pubs and seedy clubs. In any case, the film is about auditioning amateurs for striptease in what appears to be a club for women, where the compère is a woman who speaks with a cut-glass BBC accent.

The 1970s was the heyday of the women’s movement. It would be incorrect to think that through her films Thalma was speaking for or against it. Inevitably, she must have been responding as a woman to society as it then existed, and in this sense, she reflected it. In the heavily critical camp, some reviewers (both male and female) of Amateur Night portrayed the strippers as ‘pathetic’, ‘grotesque’, ‘pitiful’, and ‘ill- assorted’, and the film’s message as misogynist. In the Monthly Film Bulletin (1977) the reviewer noted the X certificate given by the British Board of Film Censors and the rejection of the film by one festival, and by some audiences, for its sexism. The female reviewer was disgusted by the female caricatures depicted in the film. In fact they were described as ‘girls’, and one even as a ‘schoolgirl’, remarkable for being fat or flat-chested. They were clearly not seen as a good advertisement for womanhood. Thalma had let the side down!

In the positive camp, words such as ‘witty’, ‘quirky’, ‘melancholy’ and ‘touching’ were used. These reviewers thought that the films expressed a female perspective, and they also stressed the technical and artistic quality of the work, comparing it with Aubrey Beardsley and George Grosz. Thalma herself always claims that the characters portrayed in her films reflect her own personal experience. For instance, she says that all three strippers in Amateur Night are in some sense her. Stanley was inspired by a sleepless night in Israel listening to wild cats. Thalma has little time for the women who reacted negatively to her work; for her, they simply lacked a sense of humour. She sees herself more as an artist than as a film-maker, and not one with any message for women in particular. The film Night Call is strikingly different in its atmosphere and it makes no explicit reference to women. In fact, Thalma says it was a film constructed from a male perspective, that of a close male friend at the time. We could find almost no published comment on the film.

Talking about her work, she stresses its evolution through her technical mastery of the finely drawn line and its continuity with earlier traditions in art and painting.

Thalma: An Artist’s Life is available now from Polpresa Press