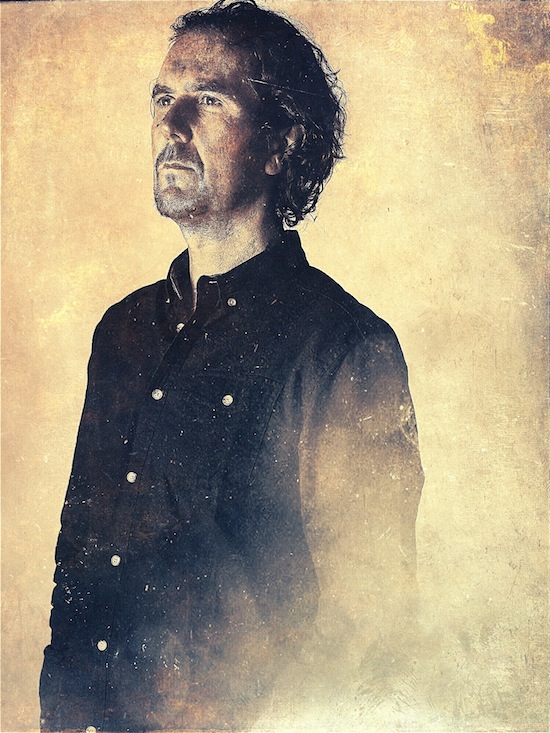

When I last spoke to Rob “The Baron” Miller, in the early months of 2012, his band Amebix was a power once more. They had just released Sonic Mass, a comeback album that did not so much confirm their legacy as define it, and were planning a tour that would make good on the promise of their 2008 reunion shows. Then, there was silence, followed by a cryptic breakup announcement, followed by more silence. At last, this past spring, there came a rumbling from the caves of Skye and a clanging from the forge. The Baron was marching to battle once more, this time under the banner of Tau Cross.

As much as Tau Cross stands on its own, it also carries the whole history of Amebix within it. The symbol of the Tau Cross is not a new one for Miller – it always shadowed his lyrics and artwork for Amebix. In a sense, then, this new band was foreshadowed in the old, or grew up from it, as a strange second rebirth. Rob and his brother Stig formed Amebix in the late seventies as a punk rock band, but quickly joined the small vanguard of bands making good on punk’s promise to kill rock & roll. From the buzzing maelstrom of Winter (1983) to the battering gloom of Monolith (1987), Amebix carved out a sonic realm of their own, twisting the sounds of the Killing Joke, Joy Division, Crass, and Motörhead into a barbarian howl against the fetters of modernity. Alongside Discharge, they spawned the subgenre of raw punk-metal now known as “crust,” but also laid the groundwork for epochal metal bands like Godflesh, Celtic Frost and Darkthrone.

Underneath the chug and the growling of Amebix, there was always an earthy songcraft and a rock & roll exuberance, and these burst to the surface on Tau Cross’ debut full-length, released this past July. Here, the fist-pounding momentum of album-opener ‘Lazarus’ clears a path for the soaring, cyclical repetitions of ‘Midsummer’ and ‘Hangman’s Hyll’, as well as traditional Motörhead rippers like ‘Stonecracker’. In Tau Cross, Miller is joined by guitarists Jon Misery (Misery) and Andy Lefton (War//Plague), veterans of the Minneapolis crust scene, and by Voivod’s mighty drummer, Away. Tau Cross wrote and recorded their debut record remotely, but all of their work is oriented towards live performance, and in the summer of 2016 they ride out on tour for the first time. They have just announced a ten-city tour of the eastern United States and Canada, from March 29 – April 9, followed by a performance on the main stage of Roadburn 2016 alongside Neurosis and Amenra, both Amebix disciples.

The following conversation took place in July, not long after the release of Tau Cross. Rob spoke about rising from the grave of Amebix, pulling together the symbols that have always followed him, and returning to the magic places of his youth.

What do you think of the notion that you’ve written a kind of folk album?

Rob Miller: Yeah, I think that’s true actually. There’s a lot of folk-i-ness about it. And I kind of indulge myself in stuff like ‘The Devil Knows His Own’ and ‘We Control The Fear’. ‘Sons Of The Soil’, too. And the heart of the record is that. It roots itself firmly in folklore, folk culture, and in the Earth itself. Particularly a quality of the earth in England, that I grew up with. It was me trying to manifest a lot of the things I’ve been trying to find words to for a long time, really.

Yes, I can hear the things we talked about after Sonic Mass came out, about landscape and such, becoming more explicit in the music here. I really liked the folky stuff on Sonic Mass, too.

RM: It’s funny how we got away with it! I really didn’t expect the other guys, or anyone else, to like it. But people can tell when it’s genuine. If you’ve connected with it, that’s what makes the difference. It might come close to being borderline cheesy, but if you’re in with it, it’s fine.

Since there’s this earthy streak in the new record, I was wondering if you listen to much folk music?

RM: Well, not really folk. I used to listen to Clannad when they first came out, I like the Celtic-mystic sound. But no, nothing that’s truly folk has influenced me all that much, it’s more of a background to everything. Particularly on Skye, where everyone seems to play something. If you don’t play the pipes, you play the fiddle, or the chant, or the bodhrán. Christine Martin, she runs Scotland’s Music, which is a big resource for Scottish folk players, and her daughter Hailey is a cellist with the Scottish National Orchestra, so I asked them both if they’d get involved with this, just for one song. And they did! They did the stuff on the end of ‘We Control The Fear’ that bleeds into ‘The Devil Knows His Own’. I just said, “Here’s the tracks, these are the quieter ones, just sketch something over these and we’ll drop them in and out as we go along.” And I like that. Next time around, there’s another musician I know locally that I want to get in for some fiddle work, and I’d like some bodhrán and stuff too.

Even in the heavy moments, too, it’s kind of folky. The songs are written around vocal lines in a way that they weren’t with Amebix, even on most of the last record.

RM: Definitely. One of the big changes between this and the Amebix stuff was me being free of having to be a bass player and singing at the same time. I played all the bass on the album, but I was recording at home, so I could play a bassline and then figure out the melody, without the problem of patting your head and rubbing your stomach at the same time. With Amebix everything was always written around playing the bass, and the rhythm that goes with that, so I was really restricted in what I could do. So it was really liberating to be able to sit back and plant a lyric or a melody wherever and however I wanted. That was the difference between this and Amebix, having the freedom to explore some different ideas vocally.

In comparison, Amebix comes off as riff-centric. Of course, the cool thing about Amebix was that the riffs weren’t really hooky metal riffs, just these pummeling rhythmic things. And the vocals locked in with that. Here, there are a lot of big, soaring hooks. Sounds like it was written to be played live.

RM: Definitely, that is the plan. Funnily enough, just before you called, I was practicing. I’ve got a mix of the Tau Cross album without any vocals to sing along to, and the other guys each have a mix without guitar, a mix without bass, a mix without drums. We do that so we can prepare for when we meet up.

I’m curious about your history with Voivod. I imagine you must have known Away from back in the day?

RM: I didn’t know him from back in the day at all! And Voivod was a band, I’ve said before, that were always on the radar. They’d be in the background, you’d hear tapes playing at gigs and stuff like that, but I never paid particular attention to them. They were in the same category for me as Slayer – bands that were integrated into the whole punk rock community without any trouble at all. The patches would be there, back in the early eighties. So they were part of our scene, really.

But it wasn’t until 2011 or 2012 that Away contacted me, asking if we’d play Roadburn, because Voivoid was curating it. We weren’t able to do it – we’d had to turn down the same offer from Neurosis a couple years before, too – but we kept in touch off and on. I had already gotten Andy and Jon in to play, and was having a really hard time finding anyone to drum. Fortuitously, Away popped up, and asked if I had any projects. So I sent him the demo, and we did the Skype thing, and we got on really well. Both of us are very conspiratorial, and he’s got his own particular spin on that, which I like. I thought, “This is a guy I can talk to for hours.” A couple months ago I flew down to Bristol for Tempest Festival to meet up with him and the rest of his band – lovely fellows. That was the first time I’d seen Voivod! They were fucking brilliant. It occurred to me that they’re really just a fun punk rock band, though very technical.

So what’s it like playing with such a technical drummer, when Amebix was so brutal and raw, and Tau Cross is such a straight-ahead “songs” band?

RM: I think he had to play down quite a lot to do this stuff, so it just sits. But when we came to the mixing process, he was very keen to explain exactly what he was doing – “You’ve gotta pay attention because there’s a little flam here, and bring out the snare right there,” and such. All these subtle bits he throws in that I wasn’t really picking up on. He does that because it’s habit for him, he has to put in some dressing.

You start to hear it more after a few listens. There are cool fills, double-pedal parts where you wouldn’t expect it…

RM: Yeah, so I’m looking forward to him bringing himself to the new songs, really. Him dictating the way that they go. It should develop. I want to keep on opening it out, letting it breathe a bit and finding out naturally where it goes.

Yeah, here you’re centring the album on your strengths and your persistent obsessions. And that’s a good place to move outwards from, organically…

RM: I had to let go of control a lot with this, to get the guitar guys on board. We had this agreement – I wrote pretty much all that stuff, on the last album, but really encouraged everybody else to bring stuff to the table. We’ve got about five or six songs by Jon and Andy already in the bag, at the moment. And Away really wants to do some complete thrash-out. He loves to just get into a Motörhead kind of groove…

I want to hear that! So, on a more somber note, how exactly does Tau Cross relate to the aftermath of Amebix? I understand if you don’t want to go there, but what’s it like not playing with Stig?

RM: It was great fun playing with Stig and we had a lot of great times, but I’m so glad I’m not in that anymore, at this point in my life. Because I’ve never had another band! I haven’t had the experience of working with other people. So it’s like, “Wow, this is great!”

Plus, no blame attributed to anybody, but with Amebix everything was like pushing string uphill. We had a really hard time of it, just getting that album out. Working against the flow all the time. Lots of difficult things were happening, and a few little tragedies.

This is the polar opposite. It’s getting together with people that just like to play guitars, hang out, have a few beers. Getting back to what was exciting about music when I was sixteen years old. It’s an open field.

My impression is that Amebix fits into the venerable tradition of British bands with two brothers who fight all the time. Jesus and Mary Chain, The Kinks, Oasis, whatever…

RM: Yeah, I don’t know, maybe that’s what made it work the way it did. But personally I came to the same situation I was in before [when Amebix ended the first time], which was like “I’m doing a lot of stuff here, and I’m not getting a lot coming back from it.” It’s brothers isn’t it, really? I wish him the best of luck, and hope he has a great time ahead.

And we made a righteous return. We came back and we did something good, and nobody has anything to complain about with that. That was a big victory, a good way to go out, so fuck it!

So was Stig not writing with you and Roy on Sonic Mass?

RM: He wasn’t really writing a lot. We jammed some ideas together in Antrim, and he came up with the riff for, ‘Here Come The Wolf’. Then he brought ‘Sonic Mass: Part I’ to the table, the acoustic song, which was nice. The rest of it was Roy and I, and Roy was doing a lot of the melodic stuff. It’s a very heavily produced album, as you can hear. A lot of what Roy calls “ear candy”, harmonic layering and other things you don’t immediately pick up on.

Looking back, now, Sonic Mass has the weight of a closing statement, but also points ahead to the Tau Cross sound. I know that you’re doing something different from Amebix, but there are also a lot of common threads, which I like.

RM: Well to be honest, all of this material was for the next Amebix album. We released the album in 2011, and were talking about going on tour, when it became obvious that we weren’t going to be doing that. That’s when things started to go a bit… wrong, you know? So I thought, “There’s a lot of energy that’s gone into this, and we’ve spent all this time focusing on doing it the right way, and this should go be played live.” That was one of the cruxes of our argument – we weren’t going to be allowed to play this live. So, what are you gonna do?

I knew I wasn’t going to go out and make a band called Amebix, because I can’t do that. It’s my brother’s band as well as mine. That would be crap, and it would do something bad to the name itself. So I knew I had to give up the name, and all the legacy that goes with it – apart from what you take with you – and go on this new adventure. For me, it wasn’t an easy decision. It was very counterintuitive. It’s the last thing you want to do.

I’d been writing stuff in that interim, whilst things were gradually deteriorating. Even when I was out with Roy, it wasn’t looking too good, but that was all with a view to Sonic Mass: Next Bit, you know?

So that’s what you hear. And to be honest, I’m not good enough technically to be able to change up my style that much. This is me really trying to push the layers, to get as big a panorama as I possibly can out of what I had brought to Amebix. So that’s why you recognise it. It’s the same energy, basically.

For me, the song that takes that up most directly is ‘Lazarus’. It’s so different, structurally – it’s a punk rock song – but thematically it’s ‘God Of The Grain Pt. II’, right?

RM: Yes. That’s a character in the immediate foreground of the song, or you’re seeing it through that person’s eyes. It’s a very up-close-and-personal song, and it is exactly like ‘God Of The Grain’. It’s a statement.

It almost seems like a musical expression of the Tau Cross logo, your symbol or sigil.

RM: Well, there are two things. That song itself is about all the anger and frustration I had with Amebix. Because that’s exactly where I was. I had been basically… buried by what had gone on. The heart of it is, “I will not be fucking buried here. I’m gonna come out of the grave and do something else.” It’s a reawakening, and a determination.

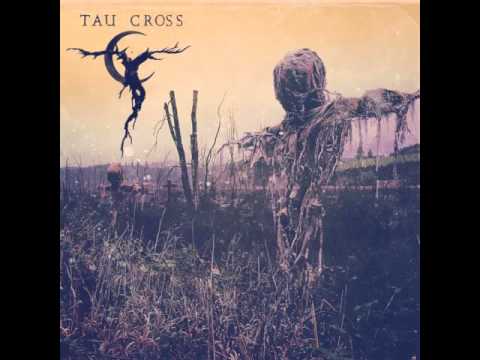

And the image of the Tau Cross, the root logo, is about the Earth, about primal energies coming up and taking form. The symbol itself I just jotted down and held up against the screen for Andy, so that he could take a screengrab and elaborate on it. The idea was to use the Tau symbol, which is organic, coming out from the ground itself, but also to use a crescent moon in the background to suggest the power of the unconscious that is acting here – to say that all of this stuff is coming up from underneath.

Somebody online made a really clever connection between the Tau Cross symbol and the opening lyric from “Sonic Mass Part 2“: “I see a burning cross upon a desert hill/Beneath a crescent moon a silhouette is rising.”

I was also thinking about it in relation to your scarecrow obsession. That’s one of the opening images in ‘Lazarus’, and a recurring part of the old Amebix album art. In the Tarot, the gallows of the Hanged Man takes the form of the Tau Cross, and a scarecrow “hangs” in the same way.

RM: Well, the body of the scarecrow is the Tau. It’s always been. You build a spike up from the ground with a crossbar, and then you hang stuff on there.

So the Hanged Man or the scarecrow, the cyclically reborn God of the Grain, sort of merges with the cross from which he’s hung?

RM: Yeah, that’s true.

And you see that in the Tau Cross sigil symbol, too, right? You’ve got this frayed and ghostly figure that is also the cross…

RM: All of these things are meant to tie together. The Tau Cross has always come up in my life, since I was a kid. Even when I rode Triumph motorcycles, you’ve got the very prominent T on there. And I always used to wear an Ankh on my motorcycle in the old days, because I believed in the protection of that, that it’d help me not crash too much. Which it did, thankfully, until I got the Harley, and I didn’t have an Ankh on that one – I crashed that fucking thing!

But also with the symbol for Sonic Mass, where you have these two sides and you’ve got the Tau with an Ankh forming, it kept coming up there. And then of course it’s in my profession, because it’s the sign of Thor, the hammer. Biblically, in the Old Testament, it’s the sign that’s put into the foreheads of those who will be saved. It’s got a lot of occult significance, but there are so many different parts.

In that song you’re also drawing on the image of the “equinoctial storm,” which is a turn of phrase so powerful that I actually remember it from one of your emails to me several years ago. Is this a recurrent symbol for you?

RM: That’s because here on Skye this is a phenomenon you can pretty much rely on every year – the equinoctial storms. At the time of the spring equinox, we get really bad gusts here, we’re talking 120 or 130 mph, really big winds. Terrible, terrible weather. But I like it. Nature itself dictates the terms: “This will happen.” And it’s a good image, you know?

Yes! It carries its own rhythm with it. And it falls into place with the scarecrow as an image of cyclical rebirth. The equinox is a moment of maximum transformation. And on the other hand, with ‘Midsummer’, you’ve got the solstice, which is a nadir or an apex, a moment of maximum stability that’s also a turning point. It’s a death, a passage into another state of being.

RM: Yes, in this case it’s the entry into the underworld. It ties in with ‘The Hollow Hills’, this idea of the fairy realm. And with the mythology of UFOs, too. There are books on this by people like Jacques Vallée, who went into old folklore and found that exactly the same images recur throughout history. We see them in different ways, according to the technology that’s around at the time, but it’s always the same kind of phenomenon – the lights within the hill, and the small people… Being taken into a world that’s just outside our timestream, and not being able to return without having lost your memory, or something like that.

‘Midsummer’ is the story of a guy falling asleep on a midsummer near one of these hills and being drawn into the earth itself. He becomes aware that he can’t breathe, he’s being stifled by the earth, and he’s got to claw his way consciously back up to see the sun rise, and have that promise of life again.

So there’s this theme of being buried… [laughs]

Reminds me of the Keats poem, ‘La Belle Dame Sans Merci’. Have you read that?

RM: I’m pretty certain I have at some point, yeah. I’m a big fan of Tennyson, and the Morte D’Artur and the Grail romances. Sometimes, if I’m dried up for lyrical ideas I’ll just plunge myself into books like that. So, which is the Keats one, then?

Well, a wandering knight comes across a fairy lady by the side of a lake, and they hit it off, and she takes him down under the hill with her. He has a great time until the spirits of other warriors, who she’s bewitched and trapped under there, scream at him to get out while he still can. He gets out, but the poem ends with him forlornly wandering the lakeshore, searching for the lady that he’s lost – he can’t let it go.

RM: Yeah, well that’s the same kind of thing, isn’t it? It’s the journey into the underworld, and often you wouldn’t be allowed to look back, or you can’t physically take anything away from there. If you do, gold turns to coal or dust or whatever. So you can’t reconcile the parallel spiritual realm, if you like, with the physical realm. The two don’t meet. But it seems like a person can walk between the two of them. At particular times of year, like midsummer, it’s more likely than others.

And at the price of sanity, in some ways.

RM: Often! Or of irreconcilable desire. The Other that you’re always longing for but can’t return to, without giving up your mortal life.

It seems like that image of the passage between worlds ties together all the places, all the settings, of the songs on the first half of the record. And these places seem to exist at the same historical time, in the Renaissance, I’m guessing? Seeing as Amebix had a very Iron Age or Medieval aesthetic, I’m interested in this move forwards in time.

RM: It wasn’t done on purpose at all, but I was very aware that what I was writing was set within the background of 17th century England. One of the pivots for that was the song ‘Stonecracker’. It’s not the most original song on the album. But it’s about the people who lived around the stone circles at Avebury and Stonehenge. They’d gather at the circles and build massive bonfires around the stones, then throw water on them, trying to crack the stones so they could break them down and drive the demons out.

The title for the song came from Pete the Roadie, who used to go out with us back in the day, and also when we were touring the States. He’s a Wiltshire boy, so he grew up in that area, and he was going on about Stonecracker Jack, so I asked him for the story. It’s a local legend, and there’s very little written about it online. You have to go to scans of the original books, old collections of folklore, and look for the pages on these characters. And that folklore thread led me on to some ideas I’ve been tempted to deal with before – the witchiness of Devonshire and Cornwall, where I grew up, and these places in the landscape which have a real sort of vibe to them, particularly these old coppice woods on the top of hills, with names like “Witch’s Wood,” or tales of something terrible that had happened there.

So I guess I had quite a lot of fun with it – those areas of fantasy mixed with other stuff as well. ‘Fire In The Sky’ was about tracing a line from the Enochian stories in the Old Testament, with their allusions to strange goings-on in the heavens, right on through to John Dee and Edward Kelley in the 16th and 17th century, and how that led in turn to Aleister Crowley and his story of the Amalantrah Working [a gateway created on Earth to allow the visitation of aliens] back in 1916. He was supposed to have opened a portal between the worlds, but since he was an intelligent man he sealed it back as best he could, no bother at all. Until Jack Parsons came along – I don’t know if you’ve heard of Jack Parsons?

Heard the name, but don’t know who he is.

RM: He was the founder of JPL, Jet Propulsion Laboratories in California, and they were the ones who made the rockets that took man to the moon. But what most people don’t know about him was that he was an arch-occultist, a real Crowleyite, and in correspondence with Crowley. He produced another working which was not parallel, but complementary to, the Amalantrah Working, or so he thought, in 1947. It was called The Babalon Working [a series of rituals designed to invoke the Thelemic godess], and it was to create the whole Moonchild thing as well. [Parsons and the Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard, aimed to "magically fertilise" a child by immaculate conception which would be born nine months after the Babalon Working ended. The Moonchild was the subject of a work of fiction of the same name, published by Crowley in 1917.] Crowley disagreed with the whole thing, he said they didn’t know what they were doing, but he died that year, and they went ahead with it. The direct result of that was the biggest UFO flap in history – the very start of the Mt. Rainier sightings. So there’s speculation that they may have opened up a portal between two worlds. There are these “fires in the sky", these lights that have been seen throughout the millennia, and have always had some of the same features, and I was trying to take the narrative all the way through, and say, “How are these things connected?”

So that’s the burning wheels from Ezekiel?

RM: The “wheels within wheels!”

The “bridge between worlds” stuff comes back again in ‘Hangman’s Hyll’, right?

RM: Yeah, the notion of being able to walk in between worlds, but the consequences of that generally being a disruption of consciousness and the psychic disintegration of the traveler – madness.

I wanted to tell this story related to the Hanged Man – the superstition about the semen of the hanging body, and how the mandrake grows where it falls. I was thinking about what would happen if a coven of witches got hold of that.

I’m interested in the idea of time, or the movement of history, that informs your work…

RM: I have a very strong feeling about history, it’s one of the few things that I really liked about school. Immediately, it was a pool I could immerse myself in. When I was in the beginning of secondary school we did the Saxons and the Vikings and the Middle Ages and the Tudors and stuff, and I was really, really into that, and then as you move up in school you get more into the Victorian period and the political machinations of empire and all that, and I had no interest in that, at all. I found myself very drawn to these earlier cultures – it was like a magical world opening up. And I could see, in the rural English landscape where I grew up, that not really that much had changed. Despite the progress of history, everything was still visible. Taking a walk in the local woods you’d come across these tumuli and the vestiges of habitation from back in Neolithic times. You’d go on to Dartmoor and find standing stones and remains of sixteenth and seventeenth architecture in the local buildings.

I grew up in a hamlet in the middle of rural Devon, where there were only three buildings in the place. It’s very difficult to find, down these tiny country lanes. And my family’s house was written down in the Domesday Book, in 1086, and it hadn’t changed a great deal when I was born there, upstairs. It was an old thatch place with these big studded oak doors that you’d bring your horse into, first of all, and then you’d take it out through the back, and hang up your cape and your riding gear. Then you’d go into the big room itself, with this massive old fireplace. Back in Devon in those days, my parents picked up this place for nothing. People wanted to get rid of these awful old buildings because they were so run down and… reeking of history. And growing up in a house that was so utterly haunted by… time itself… must have set who I was quite firmly. It was absolutely essential to my worldview.

Are there any stories or images from the area that stick with you, like places with local stories attached to them?

RM: Devon and Cornwall were full of that. It’s a very nourishing landscape. We lived right on the edge of the river Tamar. The river Tamar separates Devon and Cornwall. We’d walk down to this tiny village called Horsebridge, with a very old stone bridge that goes across the Tamar. It was named after Horsa and Hengist, these Saxon warriors who came across from what’s now Germany and took Essex, and then fought their way down through England. They came down to Cornwall, to the “wall of corn,” and tried to make conquest there. But even the Romans had failed to conquer the Cornish!

There’s always this thing about being surrounded by story. Anywhere I walked there’d be so many stories to pick from, from any particular time.

In all your work, there’s that sense of enduring presence, of radical continuity in time. It’s not just that you sing about myth and history, or that some of your songs evoke ancient atmospheres, but that the way you write songs carries its own history with it, a moving pattern marked by recurring riffs and melodies and symbols. It’s quite powerful, how Tau Cross carries that over from Amebix, especially Sonic Mass. ‘Fire In The Sky’ has a very similar vocal pattern to ‘The One’, and ‘Sons Of The Soil’ has both of the riffs that were in ‘Knights Of The Black Sun’…

RM: Does it!? [LAUGHS]

Yes! Of course, they’re not exactly the same – they’re echoes. That song echoes the binding themes that mark the beginning, middle, and end of Sonic Mass. And then there’s the post-punk guitar over it…

RM: Hmm, that’s true, thinking about that! This is one of the problems that I face… Well, it’s not really a problem! I’m trying to look for that ideal song, you know? I guess it’s always constellating around the same sort of ideas, or I’m always hunting around the same sort of ground.

It’s related to your interest in archetypes, I think. You’re following certain lines, reworking them over time.

RM: There is definitely a ground in all of the stuff that I’ve done which is recognisable, that’s what it is. For me, it’s very visual. Each of the songs has a storyline that I can see as a movie in my head. I don’t hear it so much musically, but I see it as an event that’s happening, really. And I suppose I’m going over and over the same ground. It’s like my life in music is inside a movie… Which I can adjust as I go along, if you like. I can change the narrative of that movie, but it’s within certain constricted modes, and those restrictions are – “What can I do musically? How can I make these things work? What’s the most convincing way to attack this particular thing?” It’s funny, really…

But yes, there is definitely all the same stuff there. It’s the same themes, same patterns, same landscape overall. I’m creating my own personal mythology with this, really.

Tau Cross play Roadburn on April 18