Like generations of Sahawari people, Aziza Brahim grew up in refugee camps after her pregnant mother fled the Moroccan occupation of the Western Sahara in 1976. As far back as the late 1990s the conflict in the region was being described as a "forgotten" war, and with political resolution seemingly no closer, and little to no coverage in the press, Brahim’s music expresses the social injustices felt by many Sahawari people.

Brahim was born in a refugee camp near Tindouf, in Algeria. She moved to Cuba with a study scholarship aged 11, but following a rejection to study music, she left and returned to camps in the Western Sahara, before moving to Barcelona. This much travelled background is reflected in the distinctive sound on Abbar El Hamada, the follow-up to 2014’s Soutak. The group features musicians from Spain, Senegal and Mali, resulting in an amalgamation of styles. Where Spanish guitars play mesmeric Mediterranean licks over Sahawari rhythms like Asarbat and Sharaa on traditional African instruments including djembe, sabar, tama, esgarit and the tbal drum played by Brahim. While sonically the music does not possess the ‘hard’ edge of neighbouring Tuareg rock groups, there is a great fluidity in which the desert groove unfolds over spiralling guitar riffs and propulsive rhythms.

The uplifting ‘Calles De Dajla (Streets Of Dakha)’ has this in powerful doses, with ever searching guitar lines exploring endless paths, with a focus and clarity to match the beauty of Brahim’s assured lyrics and delivery. Sounding like many voices, thanks to her own added backing vocals, the repeated lines reinforce the message, proclaiming the awakening of people in the streets and campsites.

Exiled Sahawari’s have long been kept from their homeland by fortifications that stretch 1,500 miles, known as "the wall," or ‘Los Muros’ of the album’s closing track. Brahim has spent much of her life separated from family that remained in the Moroccan occupied zone, including her father, who she never met. Brahim condemns the "criminal" partition, but finds signs that it is possible to reach higher than the walls, like the shooting stars seen "crossing the wall, unnoticed".

‘El Canto De La Arena (The Song Of Sand),’ sung in Spanish, has a breezy feel courtesy of some deft flute work, and as her voice rises Brahim takes the music along with her in new directions, as on ‘El Wad (The River),’ in which she asks God never to let the "essence of my joy" fade away. Head spinning guitar lines on ‘La Cordeillera Negra (The Black Mountains)’ dance around Brahim’s vocals, turning one way, then the next.

Brahim’s early recordings paid tribute to the poems of her grandmother, known as "the poet of the rifle" around Sahawari refugee camps, and ‘Baraka,’ a song of blessing, celebrates the teachings and example of strong women, mothers and sisters she grew up with. Malian guitarist Samba Touré, himself no stranger to unrest in his home country, brings his distinctive Songhaï blues to ‘Mani’.

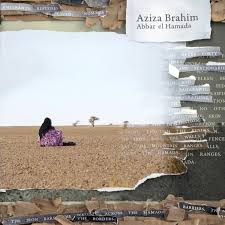

Abbar El Hamada, translates as "across the hamada," areas of desert, where sand has been blown away, leaving behind a rocky, barren landscape. On the title track Brahim’s playfully poetic words rhyme on simple pleasures such as making tea under moonlight and having "spirits renewed". For many of her family and fellow refugees that have lived their life in similar conditions there are few resources available other than words and music, "even if it is barely for a moment," as Brahim says in the album’s liner notes. This is a sound and message that reaches the heart, beyond imposed borders, curfews and barbed wire, with a dream for the end to the struggle.