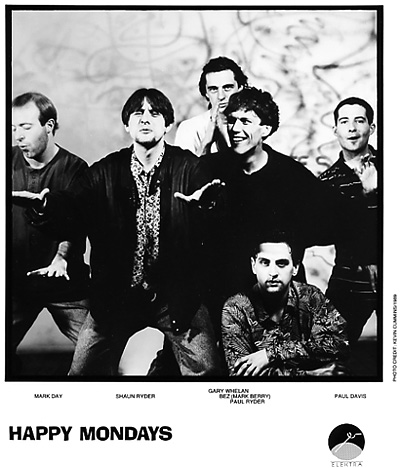

Of the four albums the Happy Mondays recorded during their first incarnation (1980-1993) most have their fair share of tales surrounding their creation. On their debut album Squirrel And G-Man Twenty Four Hour Party People Plastic Face Carnt Smile (White Out) they teamed up with John Cale as producer, a man who had recently gone teetotal around the time that they were just starting to find their groove in the world of intoxicants. Apparently his drill sergeant, tangerine-scoffing approach was somewhat at odds with band’s at the time. On Pills ‘n’ Thrills And Bellyaches they enlisted the services of DJ Paul Oakenfold to produce and to filter the hedonism of Ibiza into the rock band template. On Yes Please! they worked with Talking Heads’ Tina Weymouth and Chris Frantz as producers and relocated to Barbados, where they spent a great deal of time gorging on crack cocaine, writing off cars and then nicking and selling the recording studio’s furniture (owned by Eddy Grant) to buy even more rocks.

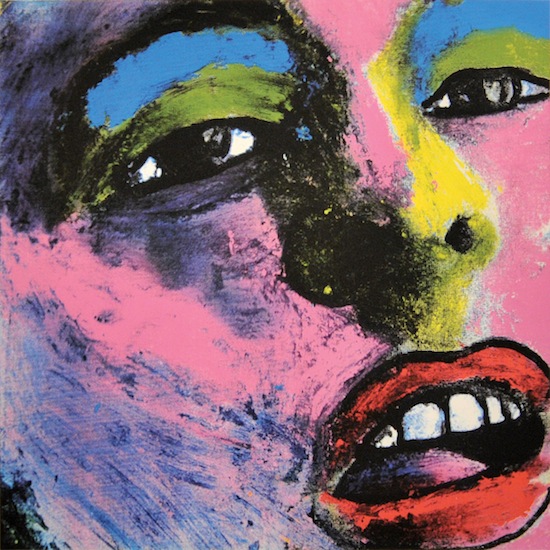

In between these wildly varying experiences lies one album without such infamy: Bummed, their second album released in 1988. Despite it arguably being their finest moment on record and perhaps being the last truly memorable piece of production work from Martin Hannett, little is known or written about its recording. Perhaps, largely, because of the unglamorous location of its genesis: Driffield.

Driffield is the town where I grew up. It’s a small market town in the East Riding of Yorkshire, somewhere you’ve perhaps driven through when you were venturing up the east coast towards Bridlington or Scarborough. It is an unspectacular town to say the least and generally void of any notable cultural occurrences or creations, Woody Woodmansey (drummer in the Spiders From Mars for David Bowie) being perhaps its biggest musical export.

It is representative of many small towns in the UK and the compact pub and club circuit that existed in 1988 when the band were in town hadn’t changed all that much when I started to frequent them illegally in the early 2000s. Slaughterhouse, the studio that the Mondays recorded in, would burn down a year after their visit in allegedly suspicious circumstances. Some years later it would become a night club called Hooters, a rancid place I would visit as an underage teenager, armed with a fill it-in-yourself fake ID I had purchased out of the back of Loaded magazine.

Some fifteen years before Martin Hannett may have been sat at a mixing desk recording an album that would eventually go gold, but it was there that I was being exposed to my first experiences of small-town British nightlife, dancing to depressing trance remixes of ‘Three Lions’. It was the same club I recall seeing a bottle of Blue WKD crashing into the side of my friend’s head whilst attached to the hand of a raging young man, as it tore open his head and blood splattered across my face and sky blue shirt, freshly bought that day from the one local emporium that sold anything resembling contemporary fashion.

It’s not unusual that such a place hasn’t been written about extensively but reading Simon Spence’s Happy Mondays: Excess All Areas, Tony Wilson’s 24 Hour Party People, Bez’s Freaky Dancin’ and Shaun Ryder’s Twisting My Melon (not two books I’d ever recommend reading back-to-back by the way), it’s surprising how little there is on record. The mentions of Driffield and these recording sessions (estimated to have taken around six weeks) amount to even less than I would have guessed – a handful of pages from thousands. Speaking with band members, their manager as well as people working on the session and in the studio, I tried to find out what really happened when the Happy Mondays hit the sleepy market town I grew up in.

“It was a strange session”, recalls engineer John Spence, who started work on the recording after a week. (The session was initially engineered by Colin Richardson, a powerhouse producer in the world of metal, having worked with Bolt Thrower, Napalm Death, Slipknot and Funeral For A Friend.) The first question, perhaps, is why Driffield in the first place? “No idea why, probably because it was cheap", says Shaun Ryder. Although manager Nathan McGough seems to think it may have been a tactic to avoid unnecessary distractions, “They chose to be away from the city [Manchester] to record somewhere where their mates wouldn’t show up. They wanted to get away from the party so they could focus on recording. If they’d made it in Manchester it would have got out of hand.”

Despite the seemingly incongruous location, studio-wise Slaughterhouse was considered by many to be a decent facility back then and had been a go-to place for many of the goth bands of the 80s, with Sisters Of Mercy and The Mission both recording there, alongside other such groups as Loop, In The Nursery and the aforementioned Napalm Death and Bolt Thrower whom Richardson brought there. Ian Hunter, who was a “general dog’s body” at the studio during this time, recalls it being an impressive set-up, “Slaughterhouse studio one was pretty epic for the times.” As the studio’s name suggests, the building was once used for killing animals and included six large meat fridges that had been turned into recording areas.

Ryder recalls landing in the town and it not really being all that odd or different from his usual surroundings, “The planet was pretty much like Driffield. Manchester was like Driffield – that’s just how it was back then.” The group were not anticipated in any way, neither Spence or Hunter recall the band being on their radar at the time, so no chaos was predicted nor was there a sense of trepidation. A harmonious relationship between studio and band was attained pretty much from the off, with Hunter attributing this to studio manager, Dave Sinton – “Think Billy Connolly with a Belfast accent” – as being a key reason.

“I appreciate it’s hard to always see the scenario when you don’t actually know the characters involved, but, Sinton was a very charismatic ex Hells Angel – a sergeant at arms – and he was one of the most immediately likeable people I think I’ve ever met. Every month or so, a pillow-sized parcel would arrive by courier from the Angels in Northern Ireland, entirely full of grass. Everyone on the staff was always walking round with an envelope stuffed with weed, like a couple of ounces of rolling tobacco. However, having said that, you also immediately knew that if you fucked with him, life would not be worth living. I think that the Mondays immediately saw that too. They immediately saw Dave Sinton was a bit of a rebel and on their side, so there was a good karma from the start.”

This said Hunter recalls the Ryder brothers almost getting off to a more troublesome start, “My first encounter with Shaun and Paul Ryder was hilarious. The painter and decorators were up on the top floor, pulling down a false ceiling when a massive piece of it fell off and came crashing down the main staircase, just as the Ryder brothers were coming down it. I remember hearing the crash and coming out of the studio office to see what had happened, to find both of them looking like flour graders; covered in grey dust and standing next to the big chunk of ceiling that had missed them by a whisker. Dave Sinton appeared and looked up at these kids, looking over the banisters on the top floor, and in his broad Northern Irish brogue, said ‘ Hey, cuntos, you nearly hit Shaun fucking Ryder, there.’"

There had been no plan as regards making the album, nothing beyond getting the group in the studio, as McGough tells me, “Not a lot of discussions were had about the music prior to the recording session. Factory wasn’t a label that practiced A&R in the true sense of discussing repertoire. If they liked you they signed you and let you get on with it. The band demo’d some of the tracks beforehand. ‘Do It Better’ was originally called ‘E’. The only thing discussed was who would produce the album. We brought Martin Hannett back into the Factory fold, he’d been on the outside for several years after falling out with Tony Wilson. We made the peace, Martin made the record.” Ryder didn’t know much about the producer other than what most people did at the time, “It was our first time working with Martin. The only thing I really knew about him was that he’d produced New Order and Joy Division and from a Factory Records documentary when he was playing with a gun and fucking about putting it to his head – that’s all I’d seen of him, really.”

Hannett was not in fantastic shape at the time, drinking heavily (“a bottle of brandy a day” recalls Hunter) but Spence does recall him having some vision for things behind the fog, “Martin had a shape for the album in mind” he says, “Although it was very hard to tell with him, he was very uncommunicative. He was often not very with it, to put it politely.” McGough remembers a couple of defining Hannett moments from the session, “I have two clear memories of Martin Hannett producing Bummed in Driffield, the first being he had a huge pharmacology manual that sat permanently on the studio console where he worked, and it listed every prescription drug in the world, specified the function of said drug and detailed their side effects. When I asked Martin why he had it he said, ‘I used to be a chemist at ICI. I like to know how different drugs work together and what they will do to my body and my brain.’

"The second memory of Martin is connected to the first in that he seemed to spend a lot of time under the mixing desk flat on his back, occasionally shouting, ‘Do it again’ to the band. He would make them do numerous takes of the same song until they got the feel right. Everyone had huge respect for Martin, you had to because his production work for Joy Division was genius. No one had ever made records that sounded like Unknown Pleasures and Closer until he did. He was obsessed with digital delays, he would patch three of these machines together to create ‘space’ in the recordings.”

Spence remembers Hannett attempting to capture such space, “Martin set up some microphones to record the ambiance of the room, he used a configuration called MS (mid-side) which wasn’t something I’d come across before but gives a particularly wide stereo image, that was interesting.”

Spence also recalls heavy periods of productivity by Hannett followed by absences, “He would disappear for days. I went in on my first day on the Monday morning at 10am and I didn’t see anybody until Thursday. I would stay there or hover around until 10pm at night in case anybody turned up and nobody did. On the Thursday Shaun came in and asked if Martin was around, which he wasn’t, and then on the Friday morning a tall chap with a suit and a briefcase walked in and it was Tony Wilson. He introduced himself and asked how it was going and I was desperately trying to cover the fact that nothing had been done since I arrived. He took a bunch of things out of his briefcase and put them on the end of the table and said, ‘Can you make sure Shaun gets these?’ I assumed they were drugs of some description and the delivery became a weekly occurrence.” Wilson’s weekly trips to Driffield are well remembered by everyone, as Hunter recalls when asked what Wilson’s role during the recording sessions were. “Chief vendor of creative stimulants and enthusiasm”, he says. “Tony Wilson would appear once a week with a box of treats, give a team talk to whoever might be out of bed, and then go and settle that week’s studio bill with Webster. That album had some long breaks in recording, due to nothing more than people just disappearing, or being too fucked up to come into the studio.”

The general productivity of the band during these sessions tends to be disputed from source-to-source; Ryder and Bez are pretty much unreliable witnesses when it comes to answering work-related questions. As the frontman points out bluntly, “My recollection of that time really is just partying, I can’t even remember us doing any work. We must have done because we got the album done but I just can’t remember us doing anything except partying.” McGough recalls them having a bit more focus though, “Everyone was on a good vibe, making great music. You didn’t really get antics in the studio with Happy Mondays, they were focused on their music, they desired to make great records, and they were always professional in that sense. They were grafters, even when they were high.” Whilst Hunter suggests it was a bit more of an extended blag and lark for the group at the time, “It was never cohesive in any way. I think that it’s important to consider that the Happy Mondays saw their career as getting lucky that someone was daft enough to think they were great, and was bankrolling them getting wrecked if they laid down a few songs. At that time, I don’t think they ever considered they might have a real career or a legacy.”

Extracting information out of Ryder and Bez is hilariously impossible, their collective memories of a six-week residential recording session really don’t extend beyond a few shared anecdotes, “We had a bit of trouble with the army one night” Bez recalls, with Ryder adding, “There was an army base nearby and we had all our pals come up from Manchester, which comprised of lads from a firm and drug dealers and party kids. We’d go to this club [Odins] and there would be army lads there who had just done a tour of Northern Ireland. They’d look at us and get some bad vibes and then we’d look back at them and there was this staring competition going on. I remember having one conversation with this kid who was getting worked up about Bez’s eyes and I was like, ‘That’s just how he is.’ My mates weren’t going to take any shit and wanted to kill these soldiers; and they wanted to kill us. But then I threw an E down one of these kids’ necks who was talking about killing Catholics in Northern Ireland and within about half an hour or so he’d come up and was doing the E walk saying how wonderful and beautiful we were. He scrounged a load of E’s off us for his pals and then after that it was all nice and peaceful. The kids we were with wouldn’t have walked away so it would have fucking gone off in there.” Bez adds, “They went from wanting to kill us to being in the studio listening to music with us.”

Bummed is one of the first ecstasy albums of the rave period, and the group were certainly still in the honeymoon period of the drug, it fuelling the mood and tone of the studio and the ensuing music. McGough says: “There was a lot of ecstasy taken on a daily basis during the making of Bummed, we took two hundred E with us but they ran out after ten days so I had to go back to Manchester and collect another hundred. Bummed is definitely an E album, perhaps the first full album ever made on that drug.” Bez confirms, “We were at the peak of our ecstasy taking”.

So, given the propensity for scattered recordings, prolonged absences, constant drug-taking and poor memory from the people making the music, I try to establish from John Spence some sort of semblance of an average working day in the studio, “They worked at their own pace. They were never in the studio for more than a couple of hours. I don’t ever remember starting anything until about 2pm, Martin would be drinking throughout most of the day and there would be various little visits to the tape machine room and he would go in there seven or eight times in as many hours to take whatever he was taking. That was just what Martin did. The tape would run for 15minutes, the length of it, and we’d just press record and let the bass player and drummer just jam. Martin would get them to record quite a lot of stuff then get rid of them and sit there for a day or so filtering through what they’d played and getting rid of what he didn’t want.” Whilst Spence recalled the group having “blind faith” in Hannett and who they trusted “implicitly” to the point that nobody would do anything unless he was around, Hunter recalls a little more friction than that. “Imagine a beardy supply teacher being given a class of feral council estate kids for a maths lesson” he starts, “It was a bit like that. Don’t get me wrong, they liked Martin Hannett, but viewed him as sweaty odorous supply teacher that they had been lumbered with, and it was more fun to wind the fucker up, than to actually do any work.”

Whether out of contempt for the group, sheer boredom or plain exasperation, both Spence and Hunter recall Hannett starting a fire in the studio one day. “Martin was a functioning alcoholic when he arrived” Hunter says. “To be honest, despite his brooding demeanour, he was a gentle soul, but he drank dark spirits or red wine, and was prone to storming off and calling everyone a cunt. He was unstable, regardless of the grief he got from the band – he set fire to the mixing desk with brandy one day.” Hunter even recalls an incident with Hannett holding the band hostage at gun point in the studio, Wilson then arriving and Hannett firing off a round two feet from his head into the wall. (Although it should be said that nobody else is able to confirm any firearm related incidents in the studio, despite Hannett’s previous ownership of a gun.) The producer’s idiosyncrasies notwithstanding, Hunter still recalls being a teenager in the company of a true sonic innovator. “Was he a genius? Without a shadow of a doubt. He achieved what all producers would love to have: a sound of their own. I think it’s more definitive with Joy Division, simply as it’s impossible to name a band who sounded like that before them. Hannett was the fifth Beatle in their case. He was much funnier and dry witted than he is often portrayed. I remember him asking me to go to the shop and get him some Wispa Bars. I noted the use of the plural and asked how many? He pulled out £20 note and just said, ‘However many that gets.’”

As for the lyrical approach on the record, it contains some of Ryder’s most stimulating, perplexing and lurid word play. Again his recollections are sparse bar the track ‘Performance’, an ode to Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg’s film of the same name, “Performance had a big effect on me. I watched that film fucking eight hours a day. At the time we were taking a lot of acid as well as E and that film would be on a constant loop from morning to night. I robbed a lot of stuff out of that.”

Hunter remembers Ryder’s lyrical approach in the studio, “I remember Shaun doing tequila and Asti Spumante slammers whilst writing lyrics on a piece of A4 on the floor." Spence remembers a similar scene, “Shaun would come in with papers that he’d written and you’d loop a three or four minute section of these grooves that had overdubs. Then he would sit, crossed-legged on the floor, with headphones on and listen to that for an hour before he’d do anything. And then sometimes he’d get up and start experimenting with some lines. All the time he was doing this, Bez would be in the room with him, dancing. All the time. I don’t remember Shaun ever doing anything without Bez being there. Over a period of hours Shaun would settle on a set of lyrics that worked for him and then Martin would be on the talk back and then something would get laid down.”

There’s a pronounced sense of brevity to Ryder’s lyrical output on the album, words that operate as snippets, singularities and pithy quips. Often these are repeated with the same degree of repetition as the itchy chug of the guitar or the synchronised force of the rhythm section. A less is more output – one that was intentional or because it was less work is anyone’s guess. However, people have spent decades tripping up over themselves attempting to describe the surging euphoric blast that is a powerful ecstasy experience but in the hands of Ryder he needed nothing more than the refrain on ‘Do it Better’:

“Good, good, good, good, good, good, good, good, good, good, good, good

Double double good

Double double good”

While gloriously playful this is still simplistic to some and no doubt agonisingly stupid to others. These are words concocted by someone who has pushed himself far and high on ecstasy during the kind of rush that arrests both body and mind. It is the only sort of response you can have to someone asking, “Are you alright?” To be reduced to the primitive and the physical: raised eyebrows, deep and long exhalations and a mischievous, winking smile. The same sort of exhalations and hisses are scattered throughout the song but these alone cannot capture the simple bliss of being clattered beyond words so Ryder spits them out from the perspective of (or as) someone with a chemically limited vocabulary: “Good. Double good.” If you’re looking for a visual representation of this state then keep an eye on Ryder’s face during the video for ‘Wrote For Luck’ because that is the sight of a man having a very, very good time.

Musically, the primary basis for Bummed seems to have been simple and unplanned: have the rhythm section of Gaz Whelan and Paul Ryder find some sort of groove from an improvised jam, lock into it and simply build from there. This suited the group’s philosophy as a whole, not to mention the chemicals they were ingesting. They were creating a framework onto which further experimentations could be added. In many senses Bummed – particularly the Driffield sessions – was just the laying of a foundation. Entirely finished songs never left Slaughterhouse studios; they would be tidied up, overdubbed and mixed at Strawberry Studios in Stockport. What had been laid down in Driffield was just a beat for the band to dance to, a soundtrack to their own party, laying the groundwork for what they would later expand on stage.

Their drug-fuelled hodgepodge approach of taking material as it came may have resulted in a singer being unable to remember a single notable thing about the musical experience of creating the record, however it also meant that the material never had an unmovable underpinning to which the band were tied to. A simple look at a few different live versions of the album highlight ‘Wrote For Luck’ during this period once they got it on the road proves exhilarating testament to the lengths they were willing to push their material to and how much capturing an essence or ‘feel’ was enough during the initial recordings. These three live versions hurtle through genres like a ram-raider ploughing through the steel shutters into an off license: house, post punk, indie, shoegaze, disco and some sort of ecstatic hybrid of them all. It’s a remarkable and truly unique occurrence in which a group take so much ecstasy – hell-bent on capturing their internal, fun-driven, groove – that they forget how they got there in the first place. Despite the very literal chemical nature of such an environment, there’s a real purity to such an approach – let the gut, the hips and the pills lead the way – follow the rush. This is something Hunter echoes, “I personally feel that the majority of that album was built on a bunch of random ideas with no real solid arrangements, but simply some great groove they had logged. I think the Happy Monday’s album plan was to string it out and have a big bender at Factory’s expense for as long as they could take the piss for.”

I go back to Shaun Ryder for one last word, trying to squeeze one further snippet of information, of any kind, about his time in Driffield, to which he responds, “Banging a few of those girls that worked as waitresses [in the pub – The Norseman] and having parties every night, I can’t remember the recording process at all. I just can’t fucking remember us doing one thing in that place, really. Sorry.”