By the time I reached the David Roberts Art Foundation, tucked away off Camden High Street, the projection of Guy Sherwin’s 1973/2003 Camden Road Station at DRAF Studio had just ended and there was a lull in proceedings. Located above the main gallery rooms, DRAF’s “dedicated live projects space” opened back in September; this was my first visit.

Dimly lit in between the live projections, the bare industrial loft with its wooden rafters, painted brick walls, some benches and blankets spread out on the floor for the audience to sit on, felt cozy, somehow, and more like a barn than a cinema. In small groups, people – most of them quite young – chatted and whiled time away, drinking beer provided by our hosts, as Sherwin and his partner Lynn Loo busied themselves setting things up for the next screening.

The five minutes we were told it would take them turned to ten. On one of the small benches besides the projectors Sherwin was manning, I spotted an artist-filmmaker I knew who said this was the best vantage from which to view and – more to the point – hear the live projections, according to the artists, so I opted to sit there rather than on the comfy-looking blankets. The character of a live cinema piece, as Sherwin himself later explained to me, will subtly change depending on the shape of the projection room and its acoustics, but equally on where in the room one happens to be seated.

One of five 16mm films – all between 9 and 12-minutes-long – selected for the evening’s programme, Camden Road Station was originally intended as a single projector film, like many of the films Sherwin made in the 1970s. But it was never shown that way. When Sherwin revisited the unfinished silent black-and-white and colour film in 2003, thirty years later, he reworked the materials to show them on three 16mm projectors. This method, which complicates the viewing experience as it is impossible to watch all the screens at once, is favoured by Sherwin and Loo who usually perform their multi-projector films in tandem. If Sherwin’s work is shown, Loo performs the sound and does the projection, and vice versa.

“Incidentally,” says Sherwin, “I do not regard Camden Road Station as a ‘performance,’ since once set up the projectors run themselves. But I do regard it as an example of ‘live cinema’ as no two screenings are exactly the same, and [apart from a 2010–11 screening on four digital projectors made to fill a shop window in Oslo], it is always shown on 16mm and in the presence of the artist.’

Whenever Sherwin and Loo put together a programme, they seek to contrast and find a balance between abstract films, such as Loo’s camera-less End Rolls (2009) with its fluctuating colour fields shown at the start of the evening, and figurative ones like Camden Road Station, which uses filmed footage of passengers alighting from and waiting for trains at the nearby station.

The latter piece was chosen partly due to the station’s geographical proximity with DRAF, but also because of the connection with another of Sherwin’s “train films” included in the programme, Soundtrack Augmented (1977/2013), in which the railway tracks shot from a moving train are converted into optical sounds, and the way certain architectural features of the loft – the brick wall, buttresses, exposed gas pipes – reflected the construction of the station itself, built at about the same time.

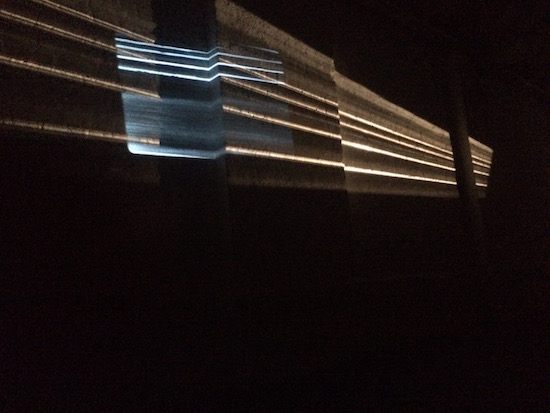

Aside from its deliberately unrehearsed and improvised character, what makes this type of cinema “live” is precisely how each piece responds to and is altered by its immediate surroundings. For their performance at DRAF, Sherwin and Loo worked closely with the architecture of the studio, projecting the films onto the buttresses and into the recesses on the side wall as well as on the ceiling and the wooden rafters, in the case of Sound Cuts (2007/2015), which does away with the traditional projection format altogether. As the title suggests, the work was made by cutting up a filmstrip (right through to the edge where optical sound appears as sound frequencies) with a splicer, before rejoining it. The resulting image is itself splintered and fragmented.

The audience facing the side wall at the studio watched the angled flashes of white light of increasing frequency sent out into the dark space like code or blazing comets, occasionally crossing a beam in their wake, each followed in rhythmic succession by a corresponding thud. Sound Cuts has been screened using anywhere between three (on this occasion) and six projectors. “There is no definitive version of the work,” Sherwin explains, “just multiple possibilities, which is how we like it.”

Sound is an integral part of Loo and Sherwin’s collaborative performances, from the whirr of projectors to the optical sound that appears both on the filmstrip and as a sound-reproducing system fitted into the projectors, generating sound from fluctuations of projected light. As a useful analogy for optical sound, Sherwin suggested I “think of a gramophone needle responding to the grooves in a vinyl record. Substitute fluctuations of light for physical fluctuations of the needle – and you have optical sound.” You could talk of ‘performing sound’, in so far as the synchronized soundtrack is fed through a mixer, making it possible to continually adjust the relative as well as the overall volume and timber of each track while the film is running.

Works such as Soundtrack Augmented, adapted for two projectors from the original 1977 Soundtrack film, have been screened alongside live music by the improv group Cranc at Café OTO in 2013 and by Loo playing guitar (though not, strictly speaking, a guitarist) in a performance at the ICA in 2014. What made the DRAF Studio version different still were the obliquely-angled projectors, aiming to offset the uneven and unusually long side wall with its buttresses and recesses. In conjunction with the use of anamorphic lenses this made for a curiously distorted, elongated image of the train tracks, funneling out so that the gap between the railway tracks widened progressively the further it extended inside the room, occasionally interrupted by dark intervals or crisscrossed by a matching yet inverted rail pattern in a smaller and more bounded rectangular projection.

For Cycles #3 (2003), bringing the evening’s programme to a close, the audience was asked to move further down inside the room as the piece was going to be projected on the end wall of the studio. This had the advantage of framing and containing the image of the circle within a circle made with paper dots and holes that had been punched directly into the filmstrip in this handmade film, repurposing materials from 1972 when Sherwin started experimenting with 16mm film.

Although the piece has been performed many times since 2003, on two projectors with an amber-coloured filter placed over one of them, on this occasion Sherwin and Loo decided to rest the projectors on their sides in order to produce a vertical image adapted to the narrow end wall. Like the railway tracks in Soundtrack Augmented, here the dots and holes reproduced on the optical sound edge of the filmstrip made up the soundtrack of the film projected by two loudspeakers. The droning sound rose to a steady pitch or thud as the frequency of the flickering dots increased, in a visual and aural equivalent of a punch.