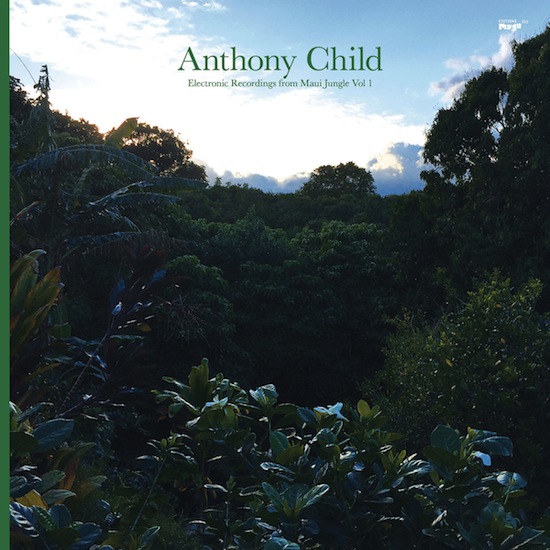

Let me remind you that Anthony Child released an album called Basictonalvocabulary way back in 1997. While that record consisted of minimal fuss, maximum impact techno – and is arguably one of the finest ‘pure’ techno full-lengths ever made – Electronic Recordings From Maui Jungle Vol. 1 is a very different type of basic tonal vocabulary. It’s primary sound source is the modular synth that anyone who has seen Child play in the past few years – under his own name, as Surgeon, or with Blawan – will likely be familiar with. Though the album is long (about ninety minutes or so), the template is set early on and varies little throughout: Child combines slow unravellings of fairly raw, saw- and square-wave tones with field recordings made in the Maui Jungle in Hawaii earlier this year. It’s an ambient album with bite, sometimes oozing into deep drone territory – with track titles like ‘Eternal Note’ you could expect no less – but just as often bouncing around with a blunt razor in its hand, serrated sounds fizzing about the place.

The album begins with the latter. ‘Bypass Default Mode Network’ is as mechanistic as its title suggests, an overtone-rich fantasia of dry, ringing sounds suspended over a strong sub-bass presence. It slowly descends into a recognisable rhythm which is almost nightmarish. There’s an unshakable sense of something wrong in the air, like a puppet show soundtracked by toy-sized organ-grinders. The following track, ‘Mr Naturals’, is the album at its most stereotypically ‘modular’, and is probably its weakest moment. A shifting arpeggiator is tweaked and fucked with over the course of seven minutes, and the results are fairly lifeless, leaving behind the snippet of field-recording which opens the track in favour of something far more mechanical and less vibrant. This contrast, between the apparently ‘organic’ recordings of the jungle itself and the synthetic, unreal, electronic sounds of the modular instrument, is the driving force behind the album. Whether Child chooses to seek a blend of the two, such as on ‘A New Moon’ or ‘The Chief’, or sets up something more antagonistic (‘Watching And Waiting’), the push-and-pull between the unpolished, sometimes unforgiving tones generated by the synth and the idea of a vast, dark jungle, dripping wet in a tropical heat, pulsing with the unknown, is what keeps him coming back, keeps urging him to go deeper, to try a new path and see where it leads.

The one question that sits in my head most often when listening to this record is this: would anyone know this music was recorded in Maui if that information wasn’t given to us in the title? I’d suspect not. At least I wouldn’t. In itself, this isn’t particularly important, but it leads one to wonder what kind of work the title is doing on behalf of the music. Just the words ‘Maui Jungle’ spark all kinds of associations, images and imagined sensations. Such is the nature of faraway places, unvisited places, exotic places. The title’s stuffiness speaks a certain kind of dry language, as if the electronics came from the jungle itself and Child is engaged in an act of documentary sound capture; a biologist or anthropologist out to record a rare bird or the last of an indigenous tribe. But the music makes no effort to place the listener in the jungle, and is not interested in a ‘faithful’ or ‘realistic’ representation of the place it takes its cues from. Child is at work on a piece of fiction – a Death In Venice, a Dublinesque – recreating a set of personal sensations and playing on his listener’s imaginations rather than seeking out a valuable but limited verisimilitude.

The record is undoubtedly atmospheric – not dark or aggressive exactly, but intense and somewhat sombre in tone – though it’s hard to say the field recordings play a huge part in this. Only rarely do they take up a central position in the track, such as on ‘Midnight Rain’ where the sound of rain in the trees persists and colours the music throughout. Usually, they get mere moments to themselves before disappearing behind the main attraction of the synthesiser. Perhaps a bird or insect will be intermittently audible, far off in the background. The work of specifying place and time – and so the work of sparking those associations and sensations that we imagine for that place – is done more by the title than the recordings of the jungle. The record could have been put together in a bedroom in Birmingham and in truth we’d be no worse off. Child’s natural musicianship, his ear for tone and for pacing, ultimately means that where it was recorded is largely irrelevant. This is not a document of a place, but a collection of work done in a place, and so it remains always about the work; the music.

This is what we have to come back to, time and time again: the sound. With a record like this, built not from melody and harmony but focused on the manipulation of basic tones – sheets of sound layered one on top of the other like scrub vegetation on the forest floor – it comes back always to the experience of being attentive to sound. What happens when you spend time listening to a saw wave? To follow along with Child’s tweaking and twisting of knobs, in lieu of any explicit compositional structure, is to give up the idea of a destination – of getting something from it – and to enjoy an inward sort of journey. Not to see something new, something exotic, but to see more clearly something that was always already there; the raw components of everyday sounds, the building blocks of music left exposed and enjoyed simply for their presence rather than their potential to convey a message or a desire. It’s not so much the potency of your chosen elsewhere, but the richness of wherever you are, if you listen closely enough.

Electronic Recordings From Maui Jungle Vol. 1 is less the construction of a story than a raw record of perception. You don’t spend time with it to find a propulsive narrative. Like the sensation of a jungle, there is an immediate impression, a taking in of the overall picture, but the longer you look, the more you allow yourself to focus, the more detail that emerges from the darkness. It stops being one singular jungle and becomes a vast collection of life-forms, visible but unknowable, an unending eruption of blood and sap coursing through veins. Rather than seeing Electronic Recordings From Maui Jungle Vol. 1 as the sounds of a jungle, perhaps it would be better to see it as a jungle of sound; an infinity waiting to come into focus.

<div class="fb-comments" data-href="http://thequietus.com/articles/19253-the-lead-review-ian-maleney-on-anthony-child-electronic-recordings-from-maui-jungle-vol-1-review” data-width="550">