When The KLF orchestrated their 1992 televised kiss off to the industry, there seemed little intent on their part to put on a good show. Replete with automatic weapons, dead livestock, and the grindcore stylings of Extreme Noise Terror, the Brit Awards version of ‘3AM Eternal’ looked and sounded awful. Even by their already well-known standards of mischief making and reputation for taking the piss, this was radical. Having mixed, remixed, sampled, and re-sampled their way to fame and small fortune with their dance music beginning in the mid-1980s, Jimmy Cauty and Bill Drummond ultimately revealed themselves as art terrorist nasties desperate to liberate themselves from the constricting straps of their listeners’ good graces.

Three years after The KLF had left the music business by way of that three minute long prank, the general public’s understanding of electronic music remained severely stunted. Throughout 1995, the UK Singles chart regularly and prominently featured disposable dance pop from nominal nobodies Alex Party, Outhere Brothers, and Whigfield alongside far more abominable novelties from Clock and Rednex. Overseas, the Americans fared no better. The upper reaches of the Billboard Hot 100 proved comparatively less welcoming to the wider Eurodance trend than the UK charts, though a handful of projects including Corona and Real McCoy made it through. Timely yet forgettable soul house acts like Ruffneck and Spirits typically topped Billboard’s weekly Dance Club Songs chart alongside suitable mixes from broadly appealing radio favorites, reflecting a sort of crowd-pleasing conservatism among the country’s top club DJs.

None of this should come as a shock to anyone who’s experienced the tiny tyrannies of the pop music marketplace, not the least of these being having certain saccharine or insipid songs foisted upon oneself repeatedly. Without the benefit of high speed Internet or social media, listeners 25 years ago had to make a greater effort to discover something other than the latest by Baby D, Livin Joy, or The Original. Still a few years shy of Napster’s game-changing adoptions on college campuses, the knowledge and time investment involved in being an active music consumer often translated to visiting a record store, reading magazines of varying quality, trading tapes with friends, or other more risky propositions for turning on.

An oversimplified interpretation of Autechre’s Tri Repetae is that it was a reactionary record, a progressive rejection of the incessant, familiar sounds of the times in which members Sean Booth and Rob Brown lived. After all, few artists in the developed world have the luxury or poverty of being able to live in total ignorance of the prevalent adjacent arts. Neither could have been completely oblivious to what was going on around them, be it the ridiculous gimmickry of ‘Cotton Eye Joe’ or the steady spew of generic one-hitters coming from Italy and Scandinavia. Even as they undoubtedly sought out the alternatives, this was the world in which Booth and Brown lived, whether they liked it or not.

Still, the duo had not emerged as obvious iconoclasts or paradigm shifters, but rather as part of an electronic brat pack of producers experimenting with both gear and genre. When Warp Records’ first Artificial Intelligence compilation appeared just months after The KLF’s aforementioned public bow, it came with some of the earliest released music under the Autechre moniker. ‘Crystel’ merged an industrial-strength boom bap backbone with Roland TB-303 acidity, while ‘The Egg’ showcased turntablist scratching over a muted electro beat. Both were forward-thinking yet wholly comprehensible hybrids.

1994’s Amber and the preceding Incunabula too bore moderate resemblances to then-contemporary styles like ambient, breakbeat, and techno such that they weren’t automatic aural deterrents. The rhythms could be unconventional in places, but overall were still largely tethered to subgenres with relatability. A DJ could find a place for ‘Basscadet’ or ‘Bike’ in a set precisely because Booth and Brown understood and respected the rave scene, going so far as to defend it with their protest EP Anti. Autechre didn’t exist in a vacuum – at least, not yet.

If the Autechre narrative has a turning point, Tri Repetae is not it. A subtler leftward pivot than Radiohead’s Kid A or The Horrors’ Primary Colours, the seventy-two minute long album isn’t overtly beholden to Cycling ’74 Max/MSP fuckery as subsequent records such as 1999’s EP7 or 2003’s Draft 7.30 which diverged deliberately into the realm of so-called difficult music. Instead, Tri Repetae was that seminal intelligent dance music record one could recommend to those looking for a beacon of difference in a sea of sameness.

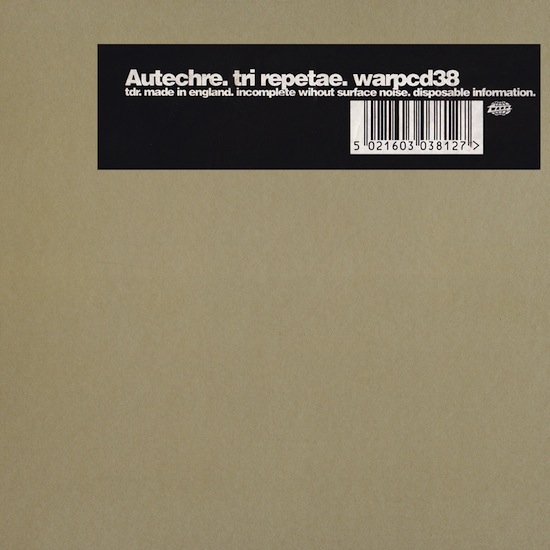

Despite its approachability for thoughtful ears, Autechre didn’t make it an easy sell. As products go, Booth and Brown made Tri Repetae as aesthetically unappealing as they could. Its drab monochromatic packaging paled in comparison to the garish colours of the rave compilations filed nearby. Amber, Incunabula, and the intervening EPs all boasted attractive covers and interiors, making The Designers Republic commissioned art for this album potentially a hindrance to purchase. It’s important to remember that, at the time, most record chains didn’t offer the means to preview an album on-site. Buyers interested in anything other than the heavily publicised fare available at marketing kiosks dubbed listening stations typically had to rely on everything but the music to make a decision. For all its damage done to the bottom lines of everyone in the industry, online piracy served as a market solution to that fundamental customer problem that retailers chose to ignore.

Absent the coming anarchic scourge of the MP3, Tri Repetae’s commercial performance in 1995 was modest. It debuted and peaked at #86 on the UK Albums Chart, disappearing the following week. Roughly a month earlier, the Anvil Vapre EP opened to #89 on the UK Singles Chart and featured music from the same sessions as Tri Repetae. Again, looking at the dance music that performed well at the time, these brief appearances should come as no surprise.

Many people who identify as Autechre fans assuredly heard Tri Repetae for the first time without ever paying. By doing so, they arguably missed out on the vinyl experience coveted by Booth and Brown. Hardly the only artists to ascribe a higher value to wax, their liner notes for the physical editions referred favorably to the added “surface noise” of playing this music on a record as opposed to on compact disc or cassette. But today, it’s more or less a dead argument, with most people doing their listening on devices and apps. Coming across an original vinyl copy of Tri Repetae from 1995 in your local record shop is a virtual impossibility. Surely it sounds very nice on TIDAL, but nonetheless not as Autechre had intended.

Today, however, technological convenience trumps the desires of audiophiles and artists. Listening back to Tri Repetae by way of Spotify, I’m reminded of when Autechre and their peers like Aphex Twin, Mu-Ziq, and Squarepusher were making music that sounded like the future to devotees such as myself. A consensus pick among fans, Tri Repetae marks a stylistic peak for Booth and Brown, the best representation of their work in the period that preceded the rhythmic irregularities and abundant software experiments that has defined their work over the bulk of their career.

Despite its rather overstated industrial characteristics, in retrospect Tri Repetae is most notable for its melodic qualities. Yes, there’s plenty of crash and bang and scrape, but the stuttering arpeggios of ‘Clipper’ and the warm pads commingling with one another over the Bambaataa beats of ‘Eutow’. The percussive clutter of ‘C/Pach’ depends on the soft synthesizer touches to achieve such evocative listening. Those who want noise can go find noise, but the inherent appeal of this beauteous music lies in its ability to make us feel something in spite of the noise.

While the next Autechre album Chiastic Slide continued to experiment with this appealing formula, Booth and Brown eventually found more value in noise than melody. 2001’s Confield, for example, treats tunefulness and harmony like bitter foes, its loveliest sounds tortured and timestretched into digital groans. Genre ceased to matter, as the duo forged ahead into the quantitative and quantum possibilities of software-based programming.

What Autechre left behind with Tri Repetae was humanity, the relatability that found Booth and Brown an engaged audience in a time of dime-a-dozen dance and vulgarian pop. Characterised now by live shows played in total darkness and album releases of inscrutable sonics, their virtual departure from the music business wasn’t as terse or discourteous as The KLF’s metallic mooning. Unlike those carnival barking showmen Cauty and Drummond, Autechre simply left without telling anyone.