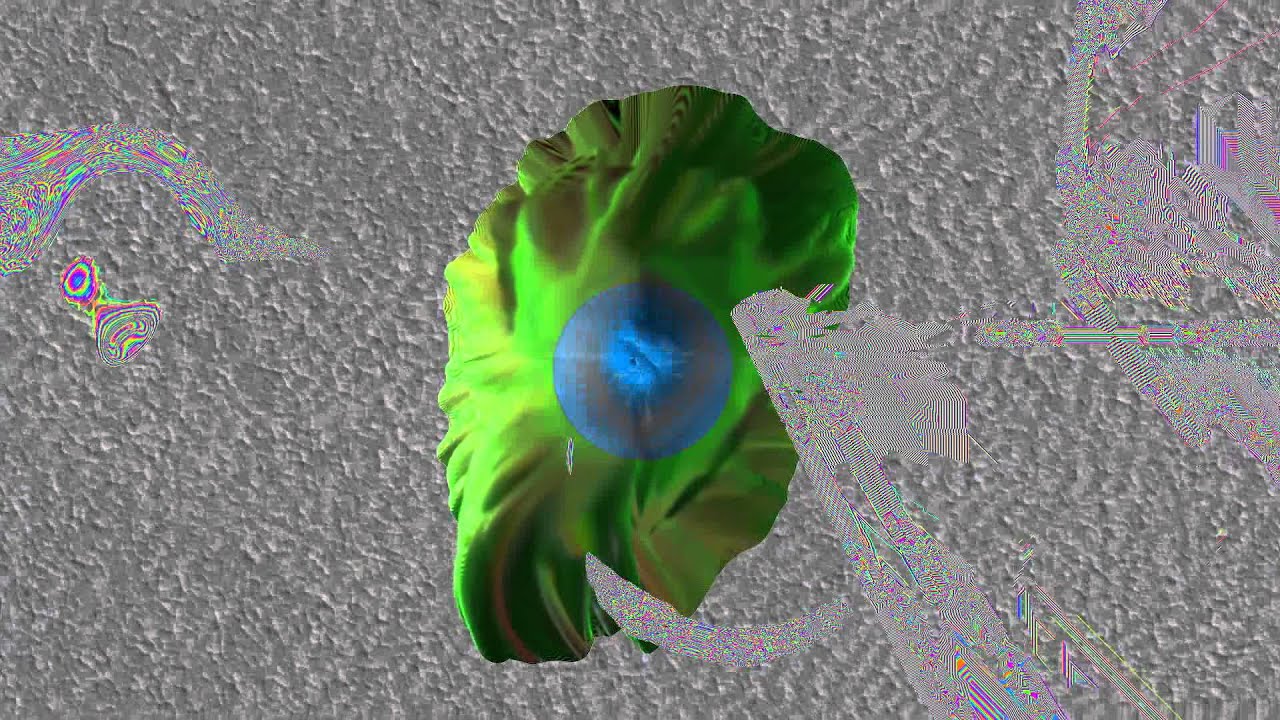

Photograph by Charlotte Jopling, courtesy of the artist and Matt’s Gallery, London

Riding the escalator down to the Northern Line at Leicester Square, the short video that comprises De Re Touch bursts in like a rude and unruly interruption amidst the smug over-familiarity of ads for Google and Boots cosmetics. A brief splurge of bodily close-ups, goo, and mutoid writing, Benedict Drew’s project for Art on the Underground comes across like a TV channel ident designed by Troma Entertainment.

There’s a guy at the bottom of the stairs playing Radiohead’s ‘High and Dry’ on an acoustic guitar and it’s just the most painful thing so I slip on my headphones and turn up the De Re Touch soundtrack, downloaded from the TFL website. It’s a festering, crepuscular collage of concrète crackles, pulsed squelches, languid drones, and pixelly, time-stretched voices, that somehow manages to strip away any vague gloss of modernity from the high-speed metropolitan transit experience and return it to a sort of mole-like burrowing through the earth, tunnelling blind and caked with mud.

“At the time,” Drew says to me via Skype, “when we started talking about [the project], that ‘beach body ready’ advert was all over the tube. I just can’t fucking believe this shit is still going on. This is 1950s-era misogyny. So that was in my mind. And I was thinking about the site of the Underground.

“People behave pretty well to each other in that space,” he continues. “Considering how crazy that space is and how many bodies are in there together in this cramped space. I’m hyper-aware of how much space I’m taking up or how hot I am or how I’m trying not to touch the business man next to me. Our bodies seem really fore-fronted in that situation and I think we as people negotiate it pretty well. So I was thinking about that in relation to the adverts. The adverts behave really badly.”

de retouch, Benedict Drew, commissioned by Art on The Underground, 2015. Photo by (c) Benedict Johnson

Drew is at home in Whitstable as we speak, sitting at his desk wearing a hoodie and a baseball cap covered in kanji symbols. Over his shoulder I can see a wall covered in framed photographs and what appears to be a banner from a 13th birthday party. An old wooden protractor rests on top of the door lintel.

He attended art school in the late 90s, studying for a BA at Middlesex before going on to the Slade. At that time, the mainstream of the art world – stuff like the YBAs and Matthew Barney’s Cremaster series – felt “kind of impossible really. I just felt completely alienated from it. At the same time, there was a moment where laptop music was coming to the fore. Labels like Mego from Vienna, in particular. There was some sort of meeting between musique concrète and techno with a really sort of punk attitude.”

He started making music with another artist, Ivan Seal, and curating festivals for the London Musicians’ Collective. At the same time, he landed a job doing live visuals for the Ninja Tune label. “Funny job,” he reflects now. “I spent a lot of time up ladders at five in the morning in Russia.”

In 2012, he had his first solo shows at Cell Project Space and the Whitstable Biennale, also appearing at the A/V Festival in Newcastle with a work called The Persuaders. The Persuaders developed out of a consideration of what he calls “digital materialism. I was thinking about the mining of the rare earth minerals that are inside computers and these things as maybe the stuff that is left over, the common earth stuff. Not the precious things but the shit that’s left over.” In The Persuaders, these sludgy remainders would sit beside the audience as they watched a video and make “approving noises” created using a Roland SH-101 synthesizer.

Pretty soon, Drew started to think he’d unfairly misrepresented his common earth clods. “I thought it wasn’t fair that they were these passive, approving, empathetic mascots. I thought they should be given the dignity of thinking about shit, being pissed off.” So he followed up The Persuaders with the Sludge Manifesto, a minute-and-a-half long HD video in which the Persuaders get radicalised.

Our view circles round a faceless but vaguely anthropomorphic bust as a series of titles insist, “We are the shit that is left over … We will make your machines grubby … We demand … An end to your value systems … Your hard surfaces … Your shirts … Your landlordism.” This, as Drew puts it, is “the Black Bloc of these sludgy lumps.”

Drew sniggers and brushes it off when I suggest that the Sludge Manifesto might stand as an actual manifesto for his own work. “It’s not my manifesto,” he says, “it’s the creatures’ manifesto.” But in the short video’s broadsides against “casting in bronze”, “printing to film”, “precious metals”, and “handmade frames” he does seem to be articulating a kind of modus operandi in opposition to much of the cash-stained grand gestures of the YBAs and their successors, the whole cult of authenticity that hangs over the artisanal turn in much recent production, inside the art world and out.

If we might tentatively grant such a programmatic quality to the Sludge Manifesto, it also shares the rudiments of its form – digital video overlaid with text and abrasive sounds – with another of Drew’s works that I saw recently at the Wysing Art Centre, near Cambridge. “It’s really emo, that film” Drew says of 2013s The Onesie Cycle. “It comes from a position of screaming from under a mountain of Primark clothes after drinking three litres of Coca-Cola and a family bucket of KFC. That kind of bad vibes.

“There’s a sort of disconnection from understanding what this stuff does to you,” he continues, describing the animus behind that film. “But speaking from a position of being inside that, under that pile of clothes, covered in grease from KFC.” These kind of apparent performative contradictions seem to abound in Drew’s work, complicating any too-easy interpretation. Earlier he had described the Sludge Manifesto as “undermining its own fiction” because on the one level it voices an “opposition to the shininess of the computer” whilst being itself an entirely digital production.

“This sort of question keeps coming up,” he says, as we talk about making critical work for commercial media like the internet – or a London Underground video hoarding, “about how you can protest something if you’re embedded in it. I think you totally can. You’re so saturated in these mechanisms that it’s impossible to live outside of. But that is absolutely no reason not to kick against things.”

Last night, he was speaking about his work at Kent University, which was “knackering,” he says. Now he’s just in the midst of working on some music for another project. It’s been a busy few months for Drew, what with the Art on the Underground project, new work in the British Art Show, a cassette release on Patten’s Kaleidoscope imprint, and before that a solo exhibition at Derby’s Quad Gallery. “At the moment, I’m trying to take some sort of breath,” he says, sucking on the dog end of a rollie. Finishing it, stubbing it out, immediately rolling up another.

But “some sort of breath” for Benedict Drew, still sounds pretty busy. He’s got a collaborative project with the artist Nicholas Brooks coming up, his work for the British Art Show needs expanding when it moves to Edinburgh in February, maybe another album of music, and then there’s his ongoing performance project “towards a radical dyslexia” that he’s hoping to expand to a full installation soon. Dyslexic himself, he claims “most of the people in art schools are dyslexic.”

“It’s sort of funny,” he says, “to think about a radical dyslexia as a movement, with a [written] manifesto… I don’t know really, yet. That’s how I feel about most of the work I make. I don’t really know what it is. Part of making the work is trying to find out. Things that are on the periphery of your knowledge is where, I think, we operate. Sometimes I make work and I still don’t know what it’s about. I find nothing out. But maybe I’m more interested in what it does than what it is or why it is.”

De Re Touch can be seen at tube stations across London until 28 February 2016. Benedict Drew’s work can also be seen at the British Art Showat Leeds Art Gallery unti 10 January when it will move to Edinburgh