Photograph courtesy of Pukkelpop/Anne-Katrien van de Velde

It’s a September Saturday night in Bloc – a warehouse-turned-club wedged into Hackney Wick’s warren of industrial units a discus throw from the Olympic Stadium (that is, a discus thrown by an athlete with as many performance enhancers in his system as the amateur shape-throwers bobbing about the dancefloor) – and several middle-aged men are making their preparations for their band’s first live PA in London since 1994. Some of these middle-aged men are semi-professional dancers: a young man’s game, you’d imagine.

Martyn Cresswell slips on a black jumpsuit onto which is stitched a large silver A specially designed for luminescence under UV lights, both mentally and physically getting into character. His colleague, Rory, sports a suit bearing the number 8. (The font is such that, if they had a dance routine, and if that dance routine were to incorporate the Charleston ‘bee’s knees’ move, the A would become an 8, and the 8, momentarily, an A: ideal for the iconography of Altern 8, their band, though in all probability not the sort of moves a breakbeat hardcore rave act would hope to project.) They look a little like handymen, or funky kids TV presenters, maybe.

Where once a performance might have been given wings with the adult confectionery du jour – Mitsis, doves, pink Calis, Supermans – now there are communal Jägerbombs and a few inauspicious stretches in the pokey former mezzanine office used as the dressing room, the sort of plywood box in which stressed self-employed businessmen might absent-mindedly rifle through invoices while contemplating sending the premises up in flames. ‘Crez’ hasn’t dabbled with disco biscuits since the mid-1990s. He spends the working week at an accident management firm, selling insurance and offering advice on legal expenses. To be frank, he’d stand a better chance being cast as a 46-year-old executive than someone whose job is to get a rave bouncing.

But that’s what he’s at Bloc to do, his fourth gig since coming out of retirement in March. And he’s more than ready for it. No nerves here, only a couple of gestures of mutual support, a jokey, half-meant “I’m too old for this”, and they’re off downstairs and through a crowd of smiley faces in smiley-face t-shirts. It’s rave revivalism, and tonight they’re gonna party like it’s 1992. It will soon be the moment they’ve all been waiting for…

The last time I’d seen Crez in the flesh was in 1987. He was wearing white elasticated trousers and a white polyester shirt, not so much a fashion statement as the customary cricketing garb. We both played for Moddershall Under-18s and back then, appositely enough, he was a Mod, rocking up for games on his Lambretta (he would later correct me that in fact he was a scooterboy, not a Mod, having eschewed the parka and threads when he cottoned on as to their impracticality for riding). He had been a decent medium-pacer, but a knee condition known as Osgood-Schlatters disease had impeded him – certainly from bowling, if not later from raving – and when he finished with the juniors he was finished with cricket. Like Jimmy in Quadrophenia, he headed off toward the chalky precipice and into oblivion, never to be seen again…

Which is not quite true. The next time I saw Martyn was in two-dimensional pixellated form – on Top Of The Pops, to be precise – by which time he’d become one of the dancers for Altern 8, the rave act from just down the road in Stafford then riding the cultural zeitgeist all the way into the Top 10. It was quite the metamorphosis, I thought, quite a subcultural sidestep. At the time it didn’t occur to me – a middle-class teenager in a market town before recreational stimulants had fully pervaded the provinces – how such a Damascene conversion might have happened. I would eventually have my own epiphany, however, when the penny would (double-)drop.

Crez had been initiated at the Hacienda by a fellow scooter boy, but full immersion would take take place over ritual weekly trips to Shelley’s Laserdome in Longton (one of the six towns that make up Stoke-on-Trent), a seminal club during the first wave of rave’s popularisation. Sasha (later of “& Digweed” fame) had a residency, and a regular stream of pilgrims came south from Manchester, whose clubs were periodically beset by drug-related turf wars, and north from Birmingham to partake of getting on one with the locals. As Stoke’s pits and pot banks felt the bite of Thatcherism and the city slipped into a post-industrial hangover, its youth cut through the gloom in the timeworn manner: by getting spannered and dancing.

One of the great demotic thrusts of rave – that is, before commodification and the grotesque star system (the literal and metaphorical elevation of DJs into pulpit-inhabiting, bourgeois wank fantasies) spawned a culture of such luxuriant vapidity that Vegas casinos are truly the only place that such a travesty of ‘house’ could call home – was the shift in focus away from the performers and onto the dancefloor, a great anonymous multitude of libidinous writhing and loved-up bonhomie, a thick texture of freaky shapes, tics and twitches, gurns and grins, euphoria and escape.

Within the huggy, druggy unity of those dancefloors was a latitude for self-expression habitually denied by an everyday existence tethered to unbending financial realities. It was unity, not uniformity, and these pleasure domes invariably threw up their characters: the faces people got off their faces with. Crez fondly recalls his own inspiration at Shelley’s: “There was a guy, Steve Ptak, known as ‘the Atmosphere Controller’. He stood in the same place by the DJ box in a pair of shorts and a pork-pie cricket hat, wearing beads. He didn’t move much. Everyone could see him. He waved his arms around, and if his hands went higher, everyone’s hands went higher.”

Back then Crez was working as a purchaser for Slimma, a company that supplied ladies trousers for Marks and Spencers, while “going out on Fridays, coming home on Sundays – when pills were bloody expensive, too: £25!” His regular companion was John Parkes, a b-boy who brought hip hop moves to the techno tableau. One summer night in 1991, as the two of them staggered out hot-cheeked and bug-eyed on to Shelley’s car park at 2am – no licence for all-nighters here, annoying when you’re still several hours from not being off your tits – an articulated lorry hoisted one of its tarpaulin flanks to reveal Altern 8, who launched into an impromptu PA as a guerrilla video shoot for new single ‘Activ-8 (Come With Me)’. Crez had yet to meet either Mark Archer or Chris Peat, Altern 8’s founder members, in person, yet is a visible presence in the video, wielding a yellow inflatable banana he’d taken out that night. As you did.

A few weeks later, just as ‘Activ-8’ was hitting the charts, Crez got his feet in the door when Altern 8’s regular dancer quit to focus on his studies, leading Archer to approach Parkes. “I said to Parkesy: ‘Try and get us in’,” Cresswell recalls. “He goes: ‘No, they want you as well!’ The first gig was that weekend at the Queen’s Theatre in Burslem, to 400 people. One week later, it was Donington Park to 8,000…”

Archer remembers that first encounter quite differently: “I hadn’t met Crez at the time, but there was always this big geezer in Shelley’s, sweating for England. He was standing next to John Parkes when I asked him to join, so I thought I may as well ask Crez as well. Him joining the band was never about his dancing ability, whether he was good at footwork or anything. It was presence, the fact that he was down the front of the stage, pointing at people, sort of intimidating you into dancing.” Presence. Crez became Altern 8’s very own Atmosphere Controller, a great Freudian superego at the centre of the dancefloor id, berating people into enjoying themselves.

Photograph courtesy of Robbie Golec (Bloc)

Peat and Archer had met in 1988 when, as Nexus 21, they started making tracks influenced by early Detroit techno and Chicago acid house (they were the first act remixed by Carl Craig, no less). Archer was also part of the original lineup of Bizarre Inc, releasing material on the in-house label of Stafford’s Blue Chip Recording Studio, the bankruptcy of which led directly to the recording of the first batch of Altern 8 tracks. “We said to the manager, ‘Look, you’ve promised us studio time’, so he gave us the keys for a few days. We recorded nine tracks, which became the Overload EP, which we released at 12-inch price. It did well.”

Built around loops, samples, pulsating bass riffs and in-your-face chord stabs, the Altern 8 sound is sometimes described as “breakbeat hardcore,” “stadium rave,” or “proto-jungle”, the array of labels reflecting the mélange of influences – from bleeps through the diva vocals of New York garage to Belgian hoover techno riffs – to which Peat and Archer were being exposed at raves. In Energy Flash, Simon Reynolds describes Altern 8 as “something like the Slade of techno,” and as Archer readily admits, there was an undeniably cartoonish bombast to the sound (though not nearly as much as would characterise many of the rave crossover hits that followed): “There were no airs and graces about it, more a sort of naivety. It was basically us trying to make something that would smash it.”

This no-frills, meat-and-taters party music was thus a departure from the more refined and cerebral Nexus 21 output, the identity of which needed to be kept separate. So, the pair agreed that the new material would have to be released under an alias. They settled on Alien 8. Their label, Network, didn’t bother with promos. It went straight to release, but when the pressings came back Alien 8 had become Altern 8. That was that. Like it or lump it, they had a typo as a name.

If the band’s name was haphazard, then its image was more biohazard. Prior to their first gig, Archer acquired chemical warfare suits and dust masks from his brother, who worked at RAF Stafford. It was an effort to create something more memorable and arresting than “two blokes with ponytails leaning over their computers”. Ironically, they got beyond “faceless techno” by wearing masks.

Looking back at it all from 2015 – over a cultural landscape in which too many musical dreams have been snared and proletarianised by X-Factor (a self-positing rather than referential concept, and surely the most savagely redundant title in TV history) and the miserable servility to the market-shaking whimsy-capital of Simon Cowell that it engenders – it would be easy to think Altern 8 were entirely contrived, a prefab rave act imagineered by some cynical, dead-eyed corporate golem and his stylist hirelings, or even perhaps by way of adherence to an entirely different form of cynicism: the subversive cynicism of Bill Drummond and Jimmy Cauty’s The Manual (How To Have A Number One The Easy Way) (in 1991, the year Altern 8’s first hit, ‘Infiltrate 202’, went to number 28 in the charts, The KLF sold more singles than any band in the world).

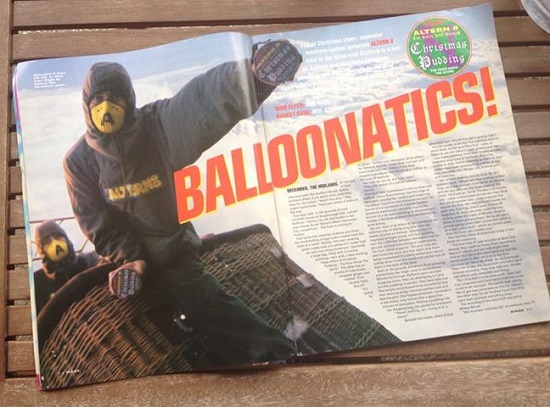

Archer is in fact wont to describe Altern 8 as “a cheapskate KLF”. They were certainly no strangers to Situationist-style pranksterism, often fabricated by the label’s PR team and, tail wagging dog, carried out when there was a bite from the press. Trainee witchdoctors (really, a blacked-up photographer) were used to exorcise traditional rock venues; Peat stood for parliament on the ‘Altern-8-ive Hardcore Party’ ticket, with a manifesto centred around compulsory raves; and the Christmas festivities would be celebrated by dropping ‘Brand-E’ puddings over Stafford from a hot air balloon. “Then we realized that a Christmas pudding was going to turn into a deadly missile if you launch it from a hot air balloon,” deadpans Archer, “so we didn’t throw them out. Besides, it was too windy to go up – but the magazine still did the piece by taking a low-angle photo of us with the sky as the background. Then we went round Stafford trying to give away these puddings to people. In vain. If you’ve got a bloke coming up to you in a chemical warfare suit brandishing a Christmas pudding then you’re probably not going to take it.”

Crez quickly became an integral and much-loved part of that Altern 8 image, an Everyman fantasy-come-true tapping into what’s probably an atavistic British affinity for blagger-dancer showmen. “Crez was our Bez,” says Archer, namechecking a man whose equally indeterminable yet utterly essential role in the Happy Mondays was perhaps best summed up by the credits to Bummed:

Shaun Ryder: Vocals

Paul ‘Horse’ Ryder: Bass

Mark ‘Cow’ Day: Lead Guitar

Paul Davis: Keyboards

Gary Whelan: Drums

Mark ‘Bez’ Berry: Bez

Indeed, Bez once thus elucidated his métier: “I do what I do.” Similarly, Crez did what he did, does what he does, although what he did do drew unfair comparison with another of the era’s dancing frontmen. “Everybody knew Leeroy from The Prodigy,” says Archer, “and were like: ‘But who’s the big guy from Altern 8?’ Everyone pitched us against them. The ‘Out Of Space’ video had a cheeky reference to us in it and people said they were taking the piss, but I never noticed.” It’s possible that he hadn’t noticed the dancer in overalls and dust mask flapping his arms about before being told to “hold it / pay close attention” to a lissom Leeroy’s mesmerisingly quicksilver shuffling, although Altern 8’s riposte, the ‘Brutal-8-E’ video, did feature a dancer, looking suspiciously like Keith Flint, in a t-shirt emblazoned with ‘The Dodgy Experience’ printed in the exact same font as that used on The Prodigy’s debut album, Experience.

It was of course little more than a storm in a teacup, and Crez certainly scoffs at the perceived comparison between him and Leeroy, admitting, rather disarmingly: “There’s no way in the world I can say I’m a good dancer!” (Which was always kind of the point with rave: it was radically inclusive – given the capacity to lose your shit in a convincingly unselfconscious, wholehearted, enthusiastic way, anyone could be the star: whence Crez.) Nevertheless, for a while the two bands were construed as vague rivals. It was a sort of Blur-versus-Oasis Britpop precursor, an ersatz animosity in which, as with pre-fight boxing hype, everyone was a winner. The two bands formed the vanguard as a slew of rave tracks invaded the Top 40 with next to no radio play. It was a genuinely countercultural (if apolitical, or only obliquely political) moment before the inevitable cash-in – the rave compilations; the cheesie novelty records (many inspired by the Prodigy’s ‘Charly’) and into which were inserted drug references that didn’t exactly require the Bletchley Park code-crackers; The Sun briefly punting smiley face merch – yet Altern 8, like The Prodigy, retained their popularity in both the clubs and the charts, if not always with the critics.

Photograph courtesy Robbie Golec

The band’s initial success – ‘Activ 8’ would peak at number 3, ‘E-Vapor-8’ reached number 6, ‘Hypnotic St-8’ made it to a respectable number 16, while ‘Frequency’ and ‘Brutal-8-E’ just missed out on the Top 40 – persuaded Crez to quit his job at Slimma. “Altern 8 was going well – not that I was making a lot of money, I never really did, but the fun was there – and I thought, well, I’m 21 years old, I’m going to enjoy this for a bit.” He topped up his earnings painting and decorating and labouring as a builder’s mate, but he was in it for adventure and sure enough, a week after that Donington Park gig, he found himself in the States. “One minute you’re in Shelley’s in Longton, the next you’re flying to New York, getting picked up in a limo, taken to Times Square Hotel and being given some money to go out and enjoy yourself with – it’s like: yeah!

The trip was both literal and metaphorical eye-opener: “The gig was in The Church, and we were competing with caged dancers suspended from the ceiling. It was mental. Two lads from Staffordshire in amongst all that hedonism – you’re thinking: is this really happening? All you can do is join in.” Having joined in, Crez later found himself walking down Broadway (“when it was just strip bars and peep shows”) at 6am in minus 10 degrees, following his nose. “They all used to take the piss because I’d go for walks and see what the world was offering me.”

Undoubtedly, that desire to “see what the world was offering” him – that curiosity and bring-it-on extroversion – had got Crez the gig in the first place, but there were also times when the world wasn’t offering up. He had to sit out the band’s first two appearances on Top Of The Pops (the first of which featured a famously arsey and anarchic performance of ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’ during which Kurt Cobain effectively fellated the mic’ in protest at the show’s producers switching formats to live vocals against a backing track set-up, reputedly an attempt to embarrass the swathes of sample-heavy rave acts laying siege to the charts’ unimpeachable musical propriety). He was persona non grata: “At the time, you used to have to have a union card to go on there. The guy said to me: ‘What do you play?’ I said: ‘I just dance.’ ‘Well, I can’t get you a union card then.’ It was a lucky break, really: the singer was flat and Steve Wright did a sketch on Radio 1 the next day taking the piss out of it.”

While the coveted union card would arrive for the band’s subsequent Top Of The Pops appearances – recorded, as ever, in the studio next door to where Eastenders was filmed: “You’re on one stage,” says Archer, “Cher’s on another, Seal, Phil Collins, and there’s Ricky Butcher watching you raving on a Wednesday afternoon” – Crez’s journey into pop music didn’t have much further to run. There were a smattering of other TV appearances, video shoots, a trip to LA and a PA in downtown Detroit at techno godfather Kevin Saunderson’s birthday party, where they were “the only five white guys in the building.”

Archer and Peat’s own Detriotian production leanings and the splintering of rave along taste lines saw them recoil from hardcore’s mutation into happy hardcore, jungle and gabber. “‘Everybody’ was supposed to be a goodbye,” says Archer, “and a thank you to everyone who’d been involved.” The Altern 8 project was parked, indefinitely (which was a shame, not least because a band whose track and remix titles adopted such a potentially limitless orthographic gimmick could no doubt have furnished us with an album based on a mid-career trip to India [Transubstant-E-8], maybe an ambient techno concept album [Medit-8] or gabber techno pastiche EP [Hyperventil-8], perhaps a single to mark the end of a three-year barren spell [‘Prevarik-8’ b/w ‘Vacill-8’] or even a remix LP, Regurgit-8). Peat had a break, while Archer involved himself with other solo projects before, he thought, picking up with Peat on the Nexus 21 project. They would never record together again.

This was no smooth parting of the ways, either: Archer hasn’t set eyes on Peat since 1994, while what little communication they have shared has been acrimonious. The dispute centres on the ownership of and rights over the band’s name, image and songs, with the question of whom it was that actually first left the band particularly contentious. Archer says Peat wanted paying for all the post-Altern 8 material he was putting out under different monikers, despite his erstwhile partner contributing nothing to them, while Peat has occasionally posted on message boards and forums, hinting at legal action over the band’s IP. Archer is adamant he is entitled not only to advertise DJ appearances using the Altern 8 name but also to resuscitate the band, sans Peat, as a live act. It is all as thickly entangled as an Italian blood feud, with zero signs of entente, cordiale or otherwise, on the horizon.

Even had circumstances been different, Crez has no regrets they didn’t ride the initial wave a little longer. “You have a shelf-life. The music has a time and a place. Rave music was starting to go mainstream. I guess you’re alright if you’re wearing a mask, but do you want to be the face of that?” It was never, for him, a question of winding it up before they lost credibility: “We never had that much credibility. We probably have more credibility now than we did then.”

Having left Altern 8 in 1993, he got married and settled down, content with his Warholian fifteen minutes. (You might argue that being “the guy freaking out at the back of the kitchen in that video with two guys eating cornflakes in masks on fast-forward” isn’t epoch-defining celebrity, but then again you could walk into hundreds of nightclubs up and down the land – hundreds of Shelley’s – and plenty of daydreamers would likely give a right bollock for the escapades, the buzz, the yarns.)

A sabbatical of several years ended in the early noughties with a few gigs riding the coattails of a first rave revival, before the dancing shoes were again hung up in 2002. In 2006 he remarried, with Archer as his best man, and those Adidas Gazelles were slipped on for another handful of shows before he slumped back onto the sofa in 2009, aged 40, ready, he imagined, for the raver’s graveyard and the more sedate world of scootering and fatherhood.

Feature continues after photographs

All photographs courtesy of BANGFACE

Not to be. In 2013 a fan in Brighton started a Facebook campaign to shunt ‘Activ 8’ to the Christmas number one slot, much as ‘Killing In The Name’ was able four years earlier to jam the dismal procession of X-Factor-sponsored automata to the summit. Where Rage Against The Machine succeeded, Rave Against the Machine fell short – it made number 33 – yet the exposure helped with a few more bookings and Crez’s six-year hiatus was soon to be over: “I got the call last Christmas: ‘Do you fancy doing a gig?’ ‘Bring it on. Here I am!’ It was like falling off a bike. I was always going to do it. I’d hate to think I’d not done anything in life, or I wasn’t going to do anything again.”

The first gig was at the BANGFACE festival in Southport, followed by a Sunday night slot beneath the giant mutant spider of Glastonbury’s Arcadia Stage, not a leisure experience available to many in the claims management sector, you’d imagine. “It’s funny what sort of life you can lead. One minute you’re stood in a board room giving a presentation about legal expenses, then you go home, grab your outfit and go and dance in front of 30,000 people.” Glasto was followed by a trip to Belgium’s Pukkelpop festival, that by the I Love Acid PA at Bloc…

The flyers for the Full-On Live Hysteria show in Hackney prompted punters to bring whistles, glowsticks, dummies, Vics and other, well, hackneyed paraphernalia of a headier time when people genuinely believed that rave (before it became just another consumerist option) could change the world from the bottom-up, starting with ego-loss, empathy and love.

Photograph courtesy Robbie Golec

There are, charmingly, a couple of Japanese tourists paying homage with dust masks embossed with the letter A (one of whom had seen Altern 8 in Japan 23 years earlier), yet the fact that the crowd don’t fully embrace this diktat and turn the night into a sub-EDM simulacrum of ‘rave’ ought to be considered a small victory for the imagination. A rave shouldn’t be a theme pub, and “rave nostalgia” is best as an oxymoron rather than a tautology – that is, at its best, the drug-music-crowd synergy of raving (or clubbing; or getting bent on empathogenic drugs and dancing to weird electronic music: call it what you will) should be about experimentation and deterritorialisation: sonic, psychic, social. A temporary bolt-hole from the force-fed familiarities of the world, that unreachable part of your soul that resists the long dark night of what was once, optimistically, known as Late Capitalism.

But then, many of the crowd are hardcore ‘ardkore fans, here for a live show from a band that hasn’t recorded new material for 21 years. They want anthems: demand and supply. On top of that, Archer says that “98% of my DJ bookings these days are for old skool sets” (which, back in the day, were, ironically, sets anchored in the preposterously futuristic sounds of early Detroit techno). These are the economic realities, the compromises of sustaining a career in the industry, which is what makes Crez’s investment in it all the purer. It’s 100 percent for shits, giggles and the buzz – from that twenty-one-year-old blagging himself a dancing gig-cum-Mr Benn trip to the geezer now zigzagging toward the low stage at Bloc. The Atmosphere Controller.

An intimately boxy main room to which access is yielded only by a double door at the back, Bloc’s dimensions bundle up the sheer rumbling, pulsating power of the Altern 8 classics, tunes that have aged considerably better than a few in the crowd. There’s not a whole lot of flow to them – they slap you in the face rather than tickle your synapses – yet by the time ‘Armageddon’ brings its air raid siren and berserker war-machine synth riff, the place is in paroxysms. (I mean, why not? It’s the weekend. England is a hellhole for all but the lizards, and it beats the fucking gym as a form of exercise.)

Like some deranged personal trainer, Crez prompts and prods his East London audience – the hipsters and the oldsters, a sea of beards on those with no chin, and multiple chins on those with no beards – the slimming effects of his raver diet long since having worn off and a middle-aged-spread’s worth of timber to propel abound the stage: “I’m 46 now: I’m not getting any younger. And I’m not the fittest bloke in the world either, so bouncing around the stage for an hour does take it out of you a little bit.” (Which begs the question as to whether performance enhancers might be judicious. “I haven’t taken pills since the 1990s, but I can always remember the feeling, and that brings me back.”)

Feature continues after photographs

All photographs courtesy of Robbie Golec

Bursts of full-on shape-throwing – the running man, ‘feeding the chickens’ – are quickly truncated, while those hallmark intimidatory strolls around the stage are now prolonged into breath-salvaging longueurs, although there’s a rationale to this choreographic economy, he insists: “The problem is, if you’re high up on stage then people can’t see your feet moving, and if you’re low down only the first row can see what your feet are doing, so your arms have got to do stuff.”

Altern 8’s set is finished by 2am and as Luke Vibert launches into some absurdly wonky techno, Crez spirits away to his hotel to rest before jumping on the 9am rattler back north to Stoke-on-Trent – back to the “executive box” he shares with two sons and a wife “bypassed by British youth culture” who has “no interest whatsoever” in watching her beloved cavort in front of a Glastonbury-sized audience. On Monday, there will be insurance claims and legal fees to sort out, the mundane nitty-gritty, yet the call of the stage can’t be muffled for too long. “I’m looking forward to doing more. Not every weekend, though. I’ve three- and four-year-old sons to think about. And my scootering. The wife keeps telling me I have to grow up soon.”

With a sixteen-year-old son from his first marriage, Crez might not be far off becoming an acid granddad. Even then, you suspect, he’ll not give the remotest of fucks about behaving himself. There’s simply too much life to be lived.