Once you’ve heard Betty Davis’ astounding vocal power, lyrical frankness and heavy, heavy funk on record, it’s exceptionally difficult to listen to anything in the same way again. Whether it’s the throat-shredding vocal and lyrical intensity of Kelis’ brutal debut track (‘Caught Out There’) or Erykah Badu’s reluctance to follow the path most-travelled I’m faced with, my thoughts immediately turn to Davis’ role in kicking down doors that were designed to prevent mould-breaking black female artists from reaching much wider audiences.

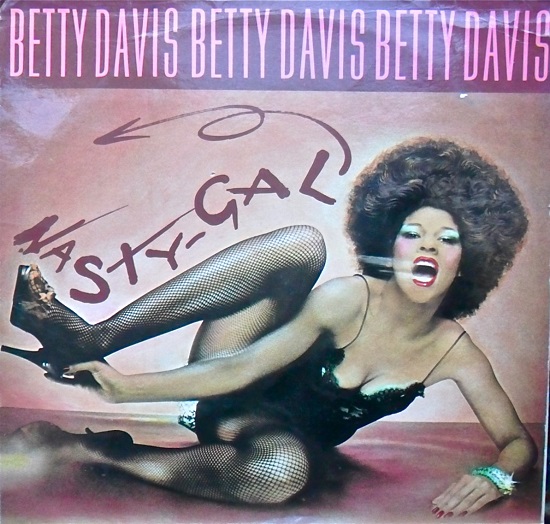

Once you’ve been confronted by the dazzlingly stylish and beautiful images beamed direct into your psyche from her album covers, you won’t see things in the same way again. The obtuse, devil-may-care attitude of Grace Jones, Millie Jackson’s sexual musings delivered in a proto rap style and the confrontational, tabloid baiting sexual provocation provided by Madonna, can all find some inspiration in the style and attitude that Betty Davis served up to a mostly bewildered world in the 1970s.

Those that dwell at the apex of today’s pop music pyramid, in the rarefied air of superstardom, (Rihanna, Beyonce, Nicki Minaj) can present a swaggering, emboldened and empowering sexuality partially as a result of the strides that Betty Davis made in confusing and confounding the music business and music fans alike some four decades ago.

But as much as other artists have benefited from Betty’s influence, her role as a pathfinder came at a cost to herself. As a black woman she carried a double burden of prejudice. A space age, funk fuelled Nefertiti? Hindsight is such a handy thing. A lot of people were not comfortable with a black woman of great intelligence, who was unashamed of her sexuality and eager to express both things on wax and in live performance. Rank hypocrisy was easily found in contemporary discourse about her voice. The same funk fans that had no problem with George Clinton’s laughing gas tones, found issue with a vocal style that dared to veer away from the mannered cut-glass perfection that seemed expected of black female soul artists. And then there were even reductive and sexist judgements made about the male company she kept. How could a beautiful black woman be considered a peer amongst the musical colossi she came into contact with? Married to Miles Davis? Friends with Hendrix, Clapton and Sly Stone? Surely she was nothing more than a glorified groupie?

These depressing issues notwithstanding, 1975’s Nasty Gal was an amazing major label debut after two deliciously devilish albums on Just Sunshine records. Island Records was fully prepared to throw its weight behind the project and offered Davis and her band (Funk House) full creative control to create what they hoped would be a stratospherically charged rise into the soul music firmament. The merest glance at the cover of the album revealed that Davis had no interest in toning down the image of sexual voracity that had been a hallmark of her two previous albums, as the arc of album cover story-telling had progressed from the playful innocence of Betty Davis (albeit in silver thigh high boots), through the Afro-futurism of They Say I’m Different to the cover of Nasty Gal, which saw her satin baby doll and fishnet stocking clad.

But things were never that simple with Betty Davis. Carnal matters do dominate on the album, and despite an opening lyric that sees her lay claim to the epithet of ‘Nasty Gal’, the duality of conflicting attitudes to female sexuality is revealed by a wave of blues inspired metaphors and a sexed-up, funk companion to Joni Mitchell’s oft-quoted ‘Big Yellow Taxi’ chorus, if you will.

”You said I was a witch now

I’m gonna tell them why, I’m gonna tell them why

You used to love it, ooh, to ride my broom honey.”

‘Talkin Trash’ is a ribald, sexually charged stick of funk dynamite, complemented beautifully by the chucking-style guitar work from Carlos Morales. Yet on the surface, this track seems to present the very opposite image of the fiercely independent woman Davis was. The lyrics seem at first to be offering her up as a sexual plaything, a toy to be picked up and put down at her lover’s behest.

”I said you can break every law with me I’m over 21.

Do whatever you want to me.”

But beneath this veneer of subservience is an undercurrent of real power here. There is no doubt about who is in control here. Yes, she offers a freedom of sexual expression, but by the end of it also states: “You’ll be glad that you were born” and she implies that she will walk away equally satiated but with you wrapped around her little finger.

Davis’ first two albums had done a fine job of introducing the world to a cocksure, libidinous woman and, like every pioneering work, this persona had been met with resistance. ‘Dedicated To The Press’ is her frank response to this criticism. And that response can be read as a solid gold, straight up Fuck You, to anyone who doesn’t like her modes of self-expression. This statement is typical of the increasingly self-referential nature of her work, fuelled perhaps by a frustration that the wider world seemed immune to the charms of unbridled funk.

None of this prepares the listener for what comes next. A song that throws the rest of the album into sharp relief, a song that some saw as a chance to glimpse the wizard behind the curtain. ‘You And I’ is a trumpet led ballad, and was co-written with her ex-husband Miles Davis, but his presence on the track is not the remarkable thing about it. It offers a snatched, rare glance at a hint of frailty in a previously unbowed and confident artist. In short, it shows that there is much more to her than merely playful sexual frisson. She skewers a male/female relationship with forensic precision.

”I’m just a child trying to be a woman

And you

You are a strange one

Trying not to be a child.”

This mood of quiet contemplation doesn’t last long though, as her trademark slamming sound returns in full effect for most of the remaining tracks. ‘Feelins’ is frenetic funk electro-shock therapy to be applied to a modern, anodyne life; while ‘F.U.N.K.’ is both an educational family tree and perfect example of the genre. Reflecting on her forebears and peers, it finds Davis acting as the gatekeeper to a music that had reached its peak and was soon to get its ass kicked by the young upstart, disco. ‘Getting Kicked Off, Having Fun’ is the kind of sinuous, insidious track that perfectly fits Davis’ leonine growl. Both the rolling funk rock and her indomitable delivery magnificently offset ‘Shut Off The Lights’’ lyrical simplicity, whilst the granite-hard groove of ‘This Is It’ sits comfortably alongside it. Album closer ‘The Lone Ranger’ lugubriously reworks earlier track ‘I Will Take That Ride’; it bristles with innuendo and double-entendre, building to a release that never arrives.

At ten tracks long and filled with enough funk to power the West Coast of the US, the scene was all set for Davis to stride into some major limelight. How could it possibly fail? Who couldn’t be lured by the magnetically alluring concoction of hard funk, unbridled sexuality and unique commanding vocal power?

Ultimately though, Nasty Gal was not destined to act as the launch pad for Davis to achieve soul superstardom. Instead it was the beginning of the self-imposed end to her recording career. Davis and the band toured tirelessly with the same electric energy as always; Island Records pushed the product as best it could and reviews were generally extremely favourable, yet sales dwindled and she was eventually cast adrift. No further music would escape a tangled web caused by label recriminations and a unique and bracing style of soul music imploding in the face of the newly emergent disco age. (Davis would viciously skewer the disco scene on later songs that languished unreleased until more recent years.)

Just as serendipity has played a role in the ascent to greatness of many an artist, so its malevolent twin misfortune has ensured an equal number never realise their full potential. The changing landscape of soul music; a general public not ready for such an aggressively smart, self-determining, frankly sexual black woman; and the machinations of label politics were responsible for the stalling of Betty Davis’ career, but, at least for us, this is by the by, as what she recorded on Nasty Gal stands the test of time as some of the lowest-down, most gut-grabbing funk ever set to wax.

Hopefully next year’s Davis sanctioned documentary will tell the full story of why she faded from view; either way two things will remain untouched – her vision and the unadulterated joy of knowing that this was an artist who didn’t bend or compromise on any count.

This article was originally published in November 2015.

Nasty Gal has just been re-issued by Light In The Attic Records, purchase it here