(Portrait of Beyibouh-al-Haj by Richard Phoenix, based on photograph by Emma Brown)

Throughout the West’s recent waking up to and reporting of the refugee crisis, the voices and stories of refugees themselves remain predominantly absent. This latest column introduces a people who were forced to leave their migratory life behind and resettle in a state of fraught permanence a long time ago, retaining their sense of self and the history of their struggle through poetry while waiting to return.

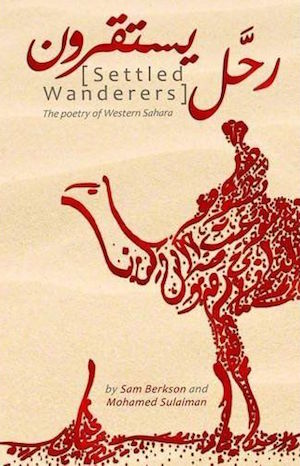

Western Sahara, a former Spanish colony on the North West coast of Africa, was invaded, occupied and annexed by Morocco and Mauritania after the death of Franco in 1975 and was renamed the ‘southern provinces of the Kingdom of Morocco’; the last colony in Africa. Marking the fortieth year of the exile of around half of the Saharawi – a formerly nomadic people – in the refugee camps in the desert town of Tindouf over the border in Algeria, Influx Press has published Settled Wanderers, the first translations into English of contemporary Saharawi poetry, accompanied by essays, poetic responses and transliterations.

“I remember as a teenager my brother saying to me something like, ‘everyone knows about Israel’s occupation of Palestine but only the real activists know about East Timor and Western Sahara’”

Poet Sam Berkson, the co-editor of the book alongside translator Mohamed Sulaiman, is a Bromley-born resident of Seven Sisters who also teaches English at a school for excluded young people in Dalston. Unlike the majority of people in the UK, Sam had been aware of the exiled Saharawi through his own reading and friendship circle long before his visit to the refugee camps that went on to inspire him to pitch the book.

“I first went out as an artist in residence with the intention of documenting the work of Olive Branch Arts. Olive Branch do brilliant work, going out every year to help young people from the refugee camps devise and perform a play.

“While I was there I also asked to meet some local poets and I came back with three translations. Talking with Kit Caless at Influx Press eighteen months later, I suggested ideas for a new book. We crowd-funded enough money for me to go back, meet more poets and pay the artists, host family, translators and driver.

“In the end, the book is not a comprehensive study of Saharawi poetry but a record of my experience of life on the camps and of the poetry I was introduced to”

It was via the Polisario Mission in London – a stand-in for an embassy as the UK doesn’t recognise Western Sahara as a country – that Sam had meetings set up with local poets and was paired with Mohamed Sulaiman Labat, an artist, translator and calligrapher who was born in the Saharawi refugee camps in southwest Algeria. Mohamed studied English Literature at Batna University in Algeria before returning to Smara camp to support his family by designing and sewing traditional clothes for his father to sell at the local market, as well as to translate and interpret for his community.

“I keep switching between translation, calligraphy and sewing. I provide translation services at festivals, conferences and many other events as well as to the many visiting delegations arriving to the camps. I have always wanted to find ways to blend art and literature; the oral and visual forms of expression, and was pleased to provide calligraphy illustrations for the book as part of this collaboration.”

If you, like many others (including myself) weren’t aware of the Saharawi, the book’s introduction, written by Stephen Zunes and Jacob Mundy, succinctly summarises the history leading up to this nearly half a century-long exile and occupation, while Mustafa El-Kattab’s essay on Saharawi folk poetry contextualises these poems as what he calls a ‘socially committed poetry’; a new era of a cultural tradition that has lasted millennia.

“The Western Saharans, coming from a Muslim and Bedouin culture, have a lot of respect for poets and their work” Sam says, “Among the Saharawi, being a poet is not a caste position like in other oral cultures. It can be a thing that both men and women do.”

Even for Mohamed, being in the presence of the poets was something immensely meaningful: “Meeting the poets was such a privilege – these people are part of a living oral tradition and have been educated by war and revolutionary struggle, adapting a thousand year old art form to deal with the situation of the present day.

“The history and literature of the region are mostly stored in the memory of older people. It’s facing a great danger of being lost because when they die, valuable treasures of literature and human experience will perish. I was very aware that we were witnessing that magic process of knowledge transmission from their generation to ours. ”

In his introductory piece in the book, Sam tells an anecdote of being called in the middle of a desert nap to be asked what he thought about Jeremy Paxman declaring that contemporary poetry was irrelevant after judging the Forward Prize for Poetry. He tells the voice on the other end of the phone of poet Al Khadra’s ‘poetic resistance’. Her poems in the book praise a reclaimed tank from the USSR, mock the King of Morocco, and celebrate soldiers breaking through The Berm – the ‘Berlin Wall of the desert’.

‘The Berm’ by Al Khadra translated by Sam Berkson and Mohamed Sulaiman

The king built the Berm

staking his claim behind landmines and snares,

but the army evaded it

and took back

what was already theirs

Her poetry, like that of all the poets, is vital for their cultural identity, it’s paramount for morale and for keeping their struggle alive. This poetry is crucial for the survival of a people through a situation classed as a slow form of genocide and that the UN still describes as an emergency.

“The elders, such as Al Khadra, Badi and Beyibouh, and the poets of the new generation like Nadgem have in common that their first identification is not as an artist but as a Saharawi and they all see the purpose of their poetry to be for the people and for the cause of independence. When I was speaking with Al Khadra she told me that ‘all my poems are written for the revolution’.

“Many have direct experience of armed struggle. They know that in the face of a steady ‘Morocanisation’ of their homeland and continuing diplomatic impasse, there is an imperative to maintain national unity and to celebrate victories and achievements. As is often the case, art in times of struggle has practical and immediate purposes.”

“During the war from 1975 until the ceasefire in 1991, poetry was a vital means to mobilise and encourage those in the battlefields,” Mohamed adds “as well as to keep up the spirit of their families left behind.”

Al Khadra is the best known of the Saharawi poets internationally, in part due to her granddaughter the musician Aziza Brahim. Sam acknowledges there would have been more women in the book (there are 4 poems by women, 3 by Al Khadra and one by Hadjatu Aliat Swelm) if it hadn’t have been for a lack of time and resources.

As The Washington Post reported, women play a large role in the activism due to women in Saharawi society traditionally having the role of community managers; a Saharawi proverb is: ‘Only a woman can grow flowers in the desert’. In fact the most prominent and celebrated protester of the movement is Nobel Peace Prize-nominee Aminatou Haidar, who is highly praised in a poem titled by her name by Bashir Ali: ‘Do not rank her against other women/show me a man who can match her!/Tell me if you can, of an example/living or gone/who has done what she has done’.

The first part of the book is the collection of Hassaniyah poems interpreted into English by Mohamed and Sam and which are split into five sections including war, heroes and resistance today.

“Some poems take you on a nostalgic journey through the nomadic lifestyle in pre-war Western Sahara” Mohamed explains, “It’s a glimpse of what was it like to live in a lifestyle of your choosing, then you get a detailed description of the war and its atrocities in other poems depicting powerful contrast between the two times; and you get to see what it feels like to have freedom and when you get robbed of it.”

“My favourite poem is Badi’s ‘Tishuash’; ‘pleasurable nostalgia’. His words, though deceptively simple, move me in such a way that I do feel for his loss of that lifestyle and of that choice. It’s so genuine that it’s painful. But it’s so amazingly expressed that it’s pleasurable. It’s Tishuash!

from ‘Tishuash’ by Badi, translated by Sam Berkson and Mohamed Sulaiman

All that has been has gone,

(how great the living and everlasting God!)

but how beautiful this scene is!

I see it sometimes –

no particular place –

just there with the goats,

like those nights I spent

at the mouth of a well,

making the wet sand my bed.

Enchanted by night’s music:

the howl of wild dogs

and insects’ whine.

[…]

How come, my brother, you do not remember this:

The sweet life full of living?

It is no longer with us,

and if tishuash could bring it back

it would add tishuash

to the tishuash

of my tishuash.

A section comprises poems about the protest of Gdeim Izik that took place in 2010 and which ended with over 3,000 arrests and resulted in the death of an eleven-year-old boy from an attack from Moroccan forces.

‘Activists from inside the Occupied Territories left the capital L’Ayoune and set up a tented protest camp on Gdeim Izik hill, just outside the city. It pointed the way for future non-violent resistance led by civil society rather than by the government or the army,” says Sam.

“Noam Chomsky described it as the start of the Arab Spring. Although most British people have never heard of it, it could probably be said that the ‘Haima’ (tents) of Gdeim Izik led the way for the revolution in Tunisia, the Indignados movement in Spain, the tents of Tahrir Square and the Occupy Movment and possibly all the way to the election of Jeremy Corbyn.”

The translation process itself was particularly complex and multi-layered, with the oral dialect of Hassaniyah being written into Arabic, literally translated, and composed into English-language poems.

“All translation is difficult, poetry particularly so, and this project was beset with difficulties. For a start, I don’t speak Hassaniyah which means that my ‘translations’ are really interpretations of Mohamed’s interpretations of the original poems.

“Many of the poets, particularly of the older generation, do not write their poems so we would record them speaking their poems and Mohamed would transcribe their recitals painstakingly into Arabic lettering. Hassaniyah is an entirely oral language and so, even in Arabic, it is a transliteration.”

“Hassaniyah is an Arabic sub-dialect, spoken widely in Western Sahara and Mauritania’ Mohamed explains, “It’s the mother tongue of the Saharawi but standard Arabic is the formal language in offices and schools.”

Certainly linked to the Saharawi’s tradition of non-violent protests including the ‘silent protest’ of wearing traditional clothing, the politics of language is vital; from the upkeep and preservation of their oral poetry in their dialect to teaching Saharawi children in the Hassaniyah dialect of Arabic and Spanish rather than the Moroccan Arabic and French used in Moroccan schools.

“We did encounter some difficulties” Mohamed agrees, “Sometimes the difficulty lay in cultural ways of expressing meanings unique to the Hassaniyah dialect which makes it difficult to translate into any language. Some of the old expressions of Hassaniyah used were also unknown to me so we had to check with the elders.

“We also had a problem identifying some geographic features, because I have never lived in Western Sahara myself. This is a problem not just for me but for the whole young generation born and raised in the camps with little physical connection to their homeland. But we consulted the poets and the elders to get the most accurate translation.”

After the initial recitals and transcriptions, the transformation would begin: “We would go through the poems line-by-line, working out literal translations with me constantly asking: ‘which word means that?’ ‘Where else do you use this word?’ ‘What is the connotation of that’ etc. On top of all this, I had to interpret poetry for an English audience who know very little about the lives of these desert people or of the forty year struggle for independence”, Sam recalls.

“For instance, Beyibouh gave me a poem which is kind of an ode to the Land Rover. During the sixteen year war with Morocco, the ELPS (the Saharawi army) used recommissioned, pickup-style 1960s Land Rovers with the cabin stripped away and a gun mounted in the back. These were the tanks of a badly-funded guerilla army and any one of these is popularly known as a ‘Dreimissa’ – a hornless goat – the title of Beyibouh’s poem. That’s quite a lot of backstory for one word.

From ‘Dreimassa (ode to the land Rover)’ by Beyibouh Eh-Haj translated by Sam Berkson and Mohamed Sulaiman

Light

And

Nimble,

Drives

Right

Over

Virtually

Every

Restriction.

[…]

I hope, Dreimessa, that these words

will do you justice.

Daring to do battle against far-superior odds,

you stripped the reputation of an invading army

and left them,

for all their high-tech weaponry and influential friends,

with nothing.

Dreimessa, you have come into your own in this war

and grown into a role no other has played before.

Seeing you from a distance, nimble and lithe,

the way you zig-zag across the night, vital and bright-eyed,

a far-off speck … and then suddenly you’ve arrived.

[…]

Then there’s the practicalities of working in a culture with a different – more appealing – sense of time, and incredible hospitality: “It can be difficult working to a deadline in a non-Western culture. My poem, ‘Why you should never do translation in the house of your Saharawi translator’ that’s in the second part of the book attempts to capture some of the amusing difficulties of that.”

The opportunity to have an unimpeded voice, to speak rather than be simply discussed, is a meaningful development for an exiled group. It humanises, fascinates and brings insight, and the more attention given to their situation the better the chance of political pressure leading to action. In reading the book, it is an acknowledgment of the liberation movement for self-determination, so far denied by Morocco on the grounds of not wishing to destabilise the area.

This is translation as a magnification and dissemination of a situation, a mechanism that can turn the no longer affecting and recycled language of rolling news into an incantation that can create empathy and solidarity thousands of miles away. It brings into existence places and lives that you never even knew existed; places and lives you didn’t know were being willed into existence.

“On the camps, there is one of Africa’s highest literacy rates and best female representation in parliament. Crime is almost non-existent. It is a shame on the world that it will not allow the Saharawi the chance to form a nation,” Sam affirms.

“It is certainly time that people in the former- and neo-colonial powers listened to the voices of the ‘post-colonial’ majority. It is not just Saharawi who are longing for a country that does not exist yet. Imagine a country set up along democratic lines, informed by traditions of Islam, Bedouin hospitality, non-violent resistance, ’60s African socialism and free market enterprise – I’d like to go there!”

Settled Wanderers is published by Influx Press.

Jen Calleja is a writer, literary translator and musician based in London. Her short fiction, poetry, articles and reviews have been published by the TLS, Structo, Asymptote and Modern Poetry in Translation, and she has translated prose and poetry from German for Fitzcarraldo Editions, Bloomsbury and PEN International. She edits the Anglo-German arts journal Verfreundungseffekt. She plays in the bands Sauna Youth, Feature and Monotony