“Hey, man. How are you doing?”

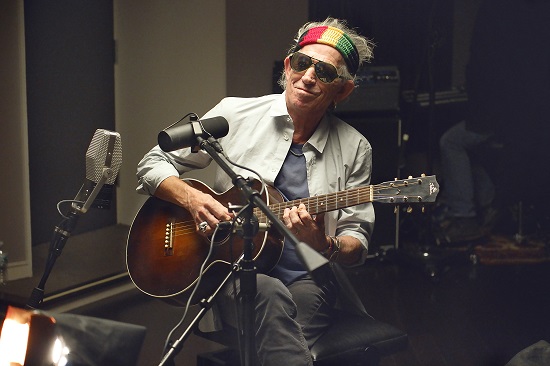

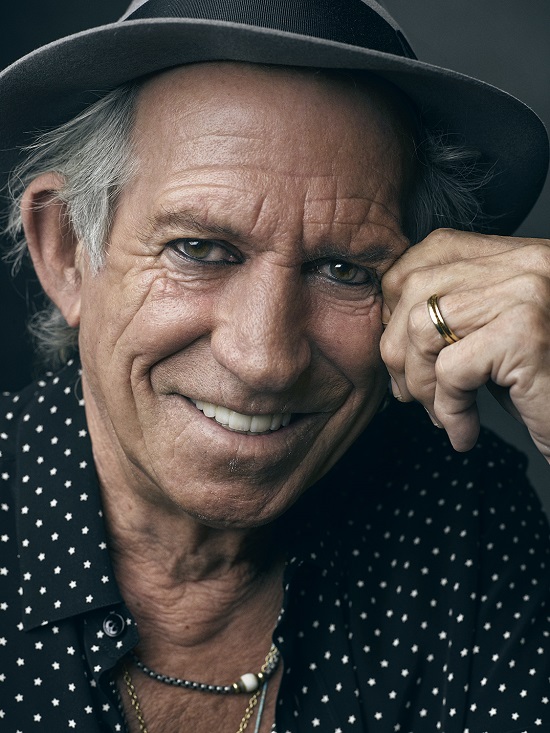

Within seconds of walking into the room, Keith Richards has put your correspondent at ease with the simplest of salutations. Shorter than you’d expect him to be, his presence takes up all the available space and it’s impossible not to warm to a demeamour that suggests a man who is completely at ease with himself while loving the fact that he’s Keith Richards. His handshake is firm and his smile is wide. His stick thin legs are encased in black jeans while the black shirt that covers his torso is undone to a degree that it reveals his bare chest and a variety of necklaces and jewelry. The bandana on his head barely conceals the shock of white hair that shoots in all directions, resembling as it does the result of a Looney Tunes cartoon explosion, while the deep lines on his tanned face are as likely the result of smiling with the phlegmy laughter that he emits with an endearing regularity as the increase in years.

Once upon a time, it was what Richards might have been smoking that would’ve raised eyebrows but now, in these health conscious times, the ashtray placed on the table in front of us will suffice for an act of mild rebellion as cigarettes are lit and enjoyed indoors. “Keith’s old school,” his PR says with a palpable sense of pride.

He’s certainly not like any 71-year-old that people of my generation grew up with. Those were people who’d lived through world wars and unimaginable hardship. But then again, in addition to be being part of the boomer generation, Keith Richards is a true original who, in a major way, helped change, shape and define popular culture in a way that so few can actually claim to have done. And while celebrity culture has increased as it comes to take on ever more ridiculous forms of banality, it rarely arrives with the kind of talent that makes an impact the way that Richards and his cohorts in The Rolling Stones have done.

We’re talking in a suite in the Savoy that overlooks the Thames and beyond it, south London. We’re a stone’s throw and lifetime away from Edith Grove in Chelsea where the young Richards, Mick Jagger and Brian Jones lived in mythical squalor and poverty in 1962 as they dedicated themselves to a relatively obscure form of music that would be given a new lease of life in their fretting and strumming hands. With Richards long departed from these shores, does his return to the capital feel like a return home or is it more like passing through a town in which he lived?

“A bit of both, actually,” says Richards, exhaling smoke. “I’ve watched the town change all around me what with all the new architecture and new looks. But this is a great view from here. But hey, London; I love the town but it’s always been changing since the Romans stuck it on! I mean, nothing stays the same; I just like to watch the changes. But they could get rid of the National Theatre though because it’s one of the ugliest dens in the world. But what goes on inside is probably more important than the look of the building, hurgh, hurgh!”

Richards is here as he prepares to release his third solo album, Crosseyed Heart, and it’s his first in 23 years. Its inception goes back five years and the album finds Richards revisiting the many styles of music that he’s lent his hand to over the decades: country blues, rock & roll, soul and reggae. With an impressive cast of characters joining him for the ride, Crosseyed Heart sees contributions from drummer and producer Steve Jordan, Ivan and Aaron Neville, Spooner Oldham and Norah Jones among others, as well as fellow hell-raiser and Stones saxophonist, the late Bobby Keys. Yet given how long the Stones have been together and the volume of extra-curricular activities by his band mates, it does seem strange that this is just Richards’ third solo outing. Why so few and why now?

Pondering the question, Richards says, “Hmm… inside of me, it’s the Stones. I only work outside of them when they’ve gone into one of their periods of deep hibernation and suddenly there’s nothing for me to do.”

Taking another drag of his cigarette, he continues, “I recorded this thing over a couple of years after I’d finished my book. So instead of recovering from living my life twice I turned round and said, ‘What’s happening? I’m supposed to be making records and I’m supposed to be playing.’ At that moment, my great friend and collaborator Steve Jordan cropped up and said, ‘Let’s go in the studio and cut a few tracks and we’ll see what happens.’ I was feeling at a loose end after the book and there seemed to be no stirring of the Stones and I love working in the studio.

“We started off with a couple of tracks to get our hand in and see what’s happening and then we did it again another month later and suddenly what we’d cut looked at us and said, ‘This is an album. We’re in for the long haul!’ and the thing kind of formed itself. It’s not something that we intended.

“The beauty of this record, as far as I’m concerned, I think it’s the only one I’ve ever made without the deadline. You must know the feeling, right? When you’re rushing around at the last minute? It was great fun to make with some top hands and some great players.”

Talking with Richards and his reasoning behind the volume of his solo work, it’s difficult not to be reminded of Led Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page. Page has recently come to the end of year-long promotion campaign for the remastering of his band’s studio albums, and it seems that both guitarists are content to serve the legacy of their respective bands first and foremost without being too bothered about making themselves a brand. Is that a fair comparison to make?

“Oh, I love Jimmy! He’s a recluse like me!” chuckles Richards mischievously. “But yes, I think that’s a fair comparison to make. As far as I’m concerned, the Stones is my band. If they happen to go to sleep for four or five years then I get antsy and find the opportunity to lay down some stuff. I want to keep my hand in. It’s what I do. The studio is my second home. I’ve had many homes but the studio is always the same. After all these years it feels like. ‘Ahh, OK, we’re at home again!’ I love working in the studio and I particularly love the atmosphere of studios and what can go on. You walk in sometimes with nothing and by the end of the evening you’ve cut a couple of interesting tracks. It’s a place of experimentation.”

But even outside of the studio, Richards admits to still playing the guitar on an almost daily basis: “If I’m at home or on the road then I usually pick it up and start playing around with it.”

Given what must be habitual playing, at what point does the action become a profound and meaningful experience in as much as he knows when a song is beginning to manifest itself?

“I know when I’m on to something when other people say, ‘I like that!’ hurgh, hurgh, hurgh!” he admits. “Y’know, you can’t work in a vacuum. If I get the nod then I’ll follow it up. I can’t really think of a song when I’ve said, ‘It has to go like this.’ I don’t go in with a fixed idea of how a song should come out. But what’s really interesting about our kind of music, y’know, rock & roll or whatever, is catching that spontaneity of things and that’s always on the top of my mind when I go in.

“Y’know, Steve’ll say to me, ‘What have you got for me today?’ and I say, ‘I haven’t got the faintest idea, Steve. Just kick off a beat’ and we’ll start to build it up. When you’re doing rock & roll there has to be an element of enjoyment and fun. I can’t get serious about it. Maybe on some of the songs you work a bit harder on the lyrics but really I’m one of those kind of guys who lets the music lead him by the nose. I don’t have a formula for this. I love the accidents and the freefall that happens in the studio when musicians get together.”

Tucked in among Crosseyed Heart’s 15 tracks are two cover versions in the shape of Gregory Isaac’s ‘Love Overdue’ and Lead Belly’s ‘Goodnight Irene’ – both of which serve to remind that Keith Richards has, over the years, probably worked with more black musicians than any of his peers. Check out just some of the names that have crossed his path: Chuck Berry, Billy Preston, Lee “Scratch” Perry, The Neville Brothers, Peter Tosh, Max Romeo, Bootsy Collins, Bobby Womack – the list goes on. And while Richards is quick to acknowledge their influence on him, he’s reticent as to whether things went the other way.

“That I couldn’t answer, if they learned anything from me,” he says. “All I know is that these guys are all great friends of mine and I’ve always been far more comfortable working with black musicians than white ones.”

Why?

“I really don’t know. Maybe it’s a matter of feel? Maybe it’s got something to do with my mum who grew me up basically on jazz and black music and so I grew up with that feel that black musicians have,” he muses. “It’s not something you can copy. There’s a sense of rhythm and you have to grow up with it, I think, and thanks to my mum I grew up with Louis Armstrong, Billie Holliday and then, of course, when Chuck Berry came along it was, ‘There it is!’ That’s when it all came together. And some of his records are still the best rock & roll records ever made.”

Naturally – or should that he nurturally? – Richards is attracted to rhythm like a moth to a light. For him – and this has been displayed throughout his music with The Rolling Stones, his numerous collaborations and the material that he’s producing now – it’s that sense of looseness that appeals to him as it frees him what he sees as the rigidity of much European music.

“I guess the other thing is that I’ve always been more interested in the roll rather than the rock,” he says, warming to theme. “Everything comes from the rock but it becomes this over-encompassing phrase for everything but to me, it’s the roll, the syncopation of rhythm sections, and what you can do with that, that makes tracks bounce a little bit more rather than sounding like a march. A lot of European music – and English, come to that – sort of relies on that marching atmosphere but it’s always been the roll, the flick and the bounce that has always fascinated me. Mind you, you need good drummers for that and I’ve been blessed with Charlie Watts and Steve Jordan!”

By his own admission, Richards is a songwriter who sticks to subjects that he knows best so it comes as no surprise that the topic of the police appears on a couple of the tracks, most notably ‘Nothing On Me’, easily one of the album’s stand out songs. Following the notorious Redlands bust in 1967 and his subsequent overnight imprisonment in Wormwood Scrubs, Richards was tried a further four times throughout the 1970s on drug charges which culminated in him facing seven years in prison after being charged with heroin trafficking in Toronto in 1977. And all that on top of police harassment throughout the decade.

“They were on my tail for quite a while,” recalls Richards of his scrapes with law enforcement officials and it how changed his view of them. “I was – and I certainly felt like it – like a target. And I’d never really thought about the cops [before] until I suddenly found out that other side to them when they’d put me up against a wall and slip something in my pocket: ‘’ello, ‘ello, Keith. What have we got here?’ I was a true blue British boy and I thought that the cops were incorruptible and I found out the hard way that that’s not true at all. And when it all came out in the wash a load of those cops spent time in jail and I didn’t, hurgh, hurgh!

“It didn’t taint my view of the police but my eyes were certainly opened to the fact that nobody’s prefect! I was brought up to believe that Scotland Yard are incorruptible but I found out that wasn’t totally true. I’m sure most of them are but at the same time I found out that not all of them were and that rankles, and I’m sure that’s why it sometimes comes up in song. ‘I don’t resist arrest/ I think it’s for the best’!”

Refusing to be drawn on his closest scrapes, he does acknowledge that the Toronto bust forced him to re-assess his relationship with the poppy.

“There were several times when I went, ‘Phew! That was close!’” he sighs, “but the Canadian one was were I was straight up against the wall and that’s when I knew that This. Has. To. Stop. I said to myself that if I can get out of here, then the drugs are all over. And at the same time, I got dependent on stuff and I wasn’t really enjoying it and it became something that I had to do just to make it to the next gig. But I don’t really regret it and I learned a lot about that side of the world. I don’t think it badly affected the way I did things or wrote things or played things but then again, I don’t recommend it. Let’s make that clear! For me, it was an experiment that went on a little too long.”

Though much of Richards’ public image is based on his brushes with the law, it’s all too easy to forget the positive aspects of his cultural contributions. Don’t forget, The Rolling Stones’ embrace and promotion of black music in the 1960s brought it to the attention of an audience that didn’t realise that it had been under their noses the whole time. Having spoken out against racism, both Richards and Mick Jagger dissuaded Gram Parsons from touring with The Byrds as the band readied itself to tour apartheid South Africa. Yet despite the many positive changes that have happened in the intervening decades, history has a habit of repeating itself.

“Oh God! It’s horrible!” grimaces Richards as the issue of Fergusson of raised. “It’s like that awful baby has reared its head again. At the same time, I don’t think you can get rid of those sorts of prejudices by the stroke of the pen. Y’know, President Johnson tried that but it doesn’t change the way people feel about things; they just re-adjust to it, as Fergusson and other places have pointed out. Look at James Blake just yesterday: one of the best tennis players in the world was laid out flat on the floor and handcuffed because he was a young black male. Obviously he got off the hook once they realised it was the wrong guy.”

He shakes his sadly: “But there is a tendency – and you can’t deny it – for institutionalised racism. I mean, they don’t think about and they don’t talk about it, they’re just like that, you know what I mean? They can’t even help it, the poor buggers. They can’t get over that hump. Although America has made long strides in that regard, I don’t think that’s happened just because of the stroke of a pen.”

For good or for ill, The Rolling Stones are always going to be viewed as a blues-rock band but this is to deny the progressive nature of their work. Their tuning and recording techniques, coupled with a jazz drummer at the helm, created a unique sound that, as attested by the numerous and inferior covers of their songs, is difficult to replicate. Furthermore, as one of the biggest bands of the 70s, the Stones’ were all over funk, reggae and disco with a credibility that eluded many of their peers. Just compare ‘Miss You’ to woeful efforts by the likes of say, Rod Stewart’s ‘Do Ya Think I’m Sexy?’ Does Richards think that the modernist aspect of the band’s music has been overlooked?

“That’s interesting,” considers Richards. “I think because we’re the Stones and that we’ve hung around for so long that maybe we have, without anyone realising, but I certainly wouldn’t want to take any kudos for anything. I mean, when we started playing in London in 1962 we started off with Chicago blues and if you wanted to start a path to stardom and fame then that was not the way to go. But without us knowing it, it really was. It really was a matter of people not hearing that music and who decided what you were going to hear out of the airwaves, or streaming as it is now.”

If anything, Richards seems happy to have opened the ears of fellow musicians and music fans of what’s possible: “I hope that we widened people’s scope of what kind of music you could play and what music you listened to. Y’know, there have been some great English blues bands in the 60s and 70s and some great singers. I loved Stevie Marriott; he was one I hoped would stick around for a while. What a great voice and guitar player. And a lot of other cats too like Jeremy Spencer and Peter Green and you’d wonder where they’d come from. These guys are playing the blues and they really are doing it.”

Richards has frequently said that he’d like ‘He passed it on’ written on his gravestone. Whilst clearly acknowledging who picked it up back in the day, are there any contemporary names that spring to mind?

“These days? You know what? Ed Sheeran is really interesting to me,” he states.

Really?

“Yeah, yeah. Lovely guitar and he’s a one-man band at the moment but he has the potential. And James Bay. They’re the two that come to mind immediately.”

He then sighs and shakes his head sadly: “Amy Winehouse was a big disappointment because I was waiting for that girl to really bloom because she was really just starting and I thought she was fantastic. It was such a shame. But there’s a high rate of that sort of thing in this business.”

Ah, yes. The infamous 27 Club of musicians that have failed to make it to 28-years-old, with one of the first members being the The Rolling Stones’ founder member Brian Jones. Given that his and Jagger’s old hometown of Dartford has been forward about honouring two of its most famous sons, does Richards think that a blue plaque saluting Jones at 102 Edith Grove should be mounted?

“Why not?” he replies. “They should have one in Cheltenham which is where he came from. I don’t see why Brian shouldn’t be recognised but it all depends on whether people want to put a plaque up. I’d donate!”

But Richards is quick to add another name – original pianist Ian Stewart who died of a heart attack in a doctor’s waiting room in 1985: “Brian was certainly very instrumental in putting the Stones together although, actually, the band really belongs to Ian Stewart. It was him that put Brian and me and Mick together in his Machiavellian little way. Stew was just a straight, upfront guy who played some of the best boogie-woogie piano that you could find in England. I always think about the Stones being Ian’s band. I’m working for him still. But I’m not paying him, hurgh, hurgh, hurgh!”

For Richards, though it always goes back to The Rolling Stones, the ride has been far from easy. Many have been the times when he’s butted heads with Mick Jagger both privately and publicly, most notably during the mid-80s in the wake of Jagger’s first solo outing, She’s The Boss, a period that Richards has referred to in the past as “world war three”. So how close has the band ever come to splitting?

“Never,” states Richards with an emphasis that suggests he’s affronted by the very idea. “They just hibernate. There’s never been any sort of talk of splitting.”

It’s now ten years since the release of their last album, A Bigger Bang, the longest period between albums in the band’s lifetime. But Richards does have good news for anyone thinking that may have been their last recorded hurrah.

“I was at a meeting with the lads three or four days ago where everybody said, ‘Yes! We must go in the studio!’” he says with a barely concealed glee. “Where or when I can’t yet say but in the near future. At last I’ve got the boys wanting to get into the studio. They all have to want to do it at the same time. That’s the thing with guys – you can’t drag ‘em in at gunpoint – but I’ve got the message that they want to. I’m hopeful, y’know?”

And with that, our conversation comes to an end. It’s impossible to shake the feeling that Richards really has every intention of playing on until he finally drops. And why the hell not? Retirement wouldn’t suit him and his enthusiasm for music as much as drawing breath is manifestly evident during our short time together. Evident? Fuck, it’s infectious. Moreover, Keith Richards actually has the ability of making the process of growing older seem a less than daunting prospect; age is just a number and it’s what you do with your time that counts. Sparking up another gasper and offering a final firm handshake, this true one-off turns on his heel and vanishes into another room leaving a plume of cigarette smoke in his wake. But he’ll be back; that much you can count on.