It’s all too easy to look on LL Cool J today as something of a side-story to the major figures in hip hop’s evolution. He wasn’t the first rapper to have a hit, and he wasn’t making the kind of politically charged musical statements that helped define the possibilities of the music in the late 1980s. When he decided to write about something other than himself and his boundless skills as an emcee, the results weren’t always completely convincing, and these days it’s almost as if we judge his worth as an emcee in the same way we might assess his latter-day career on the small and big screens: as someone who’s capable but middling. Yet back in the golden era, LL was hip hop’s first solo superstar – a teenage colossus of the mic who represented a sometimes risque, sometimes playful, always braggadocious and invariably compelling take on what being an emcee was all about. He battled and beefed with the best of them, and he made records at a prodigious clip which always cannily tapped in to hip hop’s production zeitgeist and helped push the music forward, while his innate sense of what would become popular also proved vital in gaining the music a wider audience.

His first and fourth LPs, Radio and Mama Said Knock You Out, are respectively 40 and 35 years old this year. The path between the two – musically, certainly; lyrically, possibly; in terms of flow, indubitably – tell the story of the end of the 1980s in hip hop more vividly than any other artist’s comparable releases. In a strange, almost counterintuitive way, listening to them again today you can hear LL and his production partners going backwards to move forwards, particularly on Mama Said, where you get the sense of an artist who almost felt trapped into being futuristic taking a deliberate decision to return to the music’s roots for a shot of inspiration – as if the only way he could regain the vanguard was to make music in a more traditional mode.

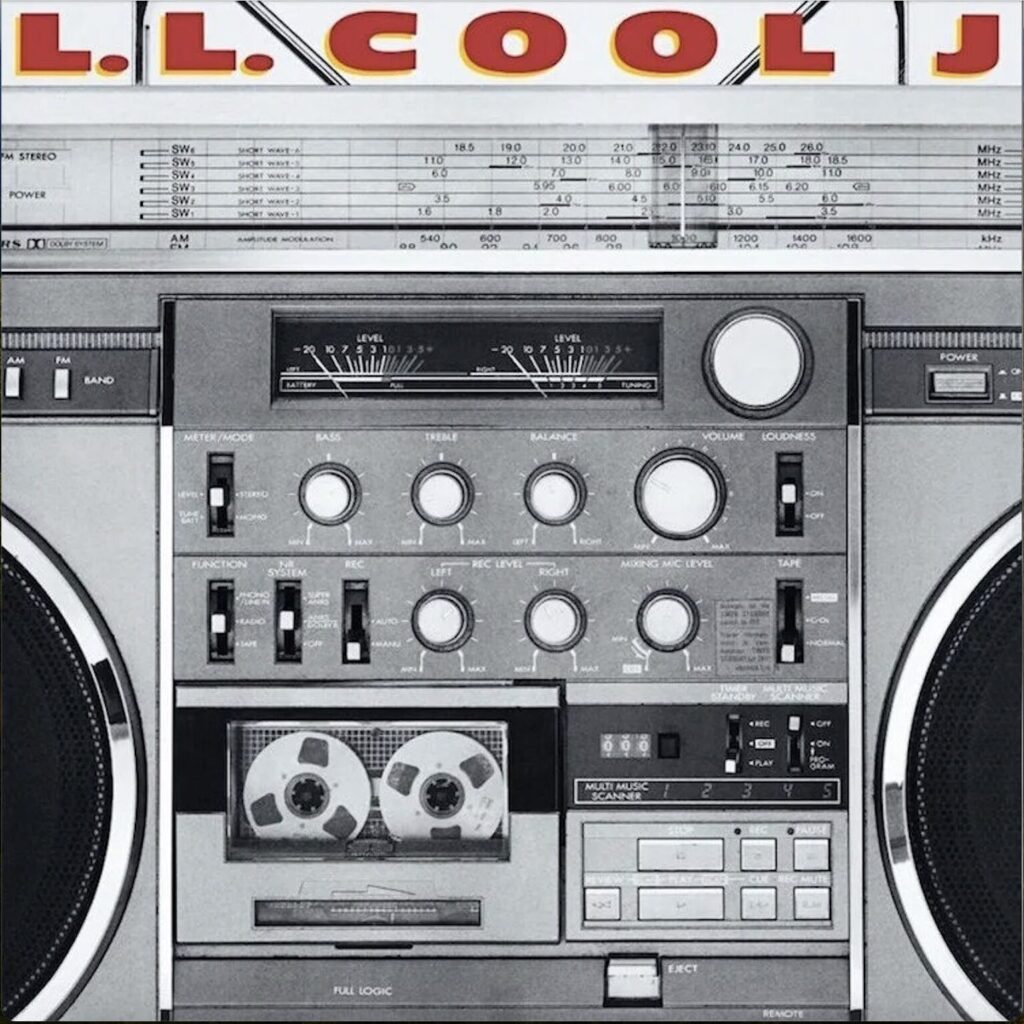

That first LP established the 17-year-old rhymesmith as one of rap’s most important and imposing personalities but also seemed to force him into a corner. The record was the result of an unlikely collaboration with hirsute rock fan Rick Rubin that not only caused the creation of one of hip hop’s most singular and arresting debut albums, but also necessitated the inauguration of the genre’s pre-eminent record label. There was no Def Jam Records when the then 16-year-old LL sent in a cassette to the New York University dormitory address printed on the label of T La Rock’s ‘It’s Yours’ single, which Rubin had produced. There still wasn’t when, months later, Ad Rock of the Beastie Boys was rummaging through the tapes that had arrived at Rubin’s student digs and pulled out LL’s demo, and urged Rubin to sign him up. Rubin had to establish the label in order to release LL’s first single. To say that ‘I Need A Beat’ changed the course of pop music would not be an understatement.

Between its appearance on that first, pre-Columbian independent, purple-coloured Def Jam 12″ in 1984, and the remixed version that dropped in as the second track on side two of Radio the next year, LL had come of age as arguably the greatest exponent of the emcee brag in hip hop history. Certainly, to that point in time, no-one had managed to compel for an entire LP with a monomaniac style that focused solely on its protagonist and his skills for its subject matter. The impact of his words and his personal presentation, though, was only half of the story: Rubin’s stripped-down take on hip hop – partly in thrall to the brutalist minimalism of classic electro, partly a result of his love of power chords and heavy beats from classic rock – gave LL’s unprecedentedly narcissist essays the air of the revolutionary.

Today, Rubin’s reputation from that era tends to rest on his production of the first Beasties album and Run DMC‘s globe-conquering Raising Hell. Yet it’s hard to imagine him making either record if he’d not already learned to shape and mould his musical ideas on Radio. History tends to record that the rock-rap fusion as a commercially viable enterprise dates back to ‘Walk This Way’, and that the moment where Steven Tyler and Joe Perry of Aerosmith break down the wall separating their studio from Run DMC‘s next door in the video for the song marks the moment where rap broke out of a specialist listenership and began its colonisation of pop’s mainstream. There’s much to be said for the argument, and the success of the Run DMC single can’t be argued with: but it’s difficult to imagine that the record would have ever been made had Rubin not worked out the basics of his first signature sound while creating LL’s near perfect debut.

‘It’s Yours’ had set out Rubin’s stall, taking some of the elements of Afrika Bambaataa’s releases on Tommy Boy but slowing down the beats and beefing up the bottom end while distilling the idea of a sample as an evocation of another sound or style and condensing it into single stabs. The tracks were programmed, usually on the Roland 808 drum machine which had a very distinctive kick-drum sound, and the samples crunched in manually, just like a DJ would do, isolating a brief fragment of music and using it as an accent rather than taking a few seconds and making a loop. Occasionally, some drums are overlaid in loop form on top of the drum machine programming, resulting in a beat that’s at once human and mechanical – a musical cyborg. Rubin uses the technique throughout Radio but it reaches its zenith on the dazzling ‘Rock The Bells’, where a cascade of percussion from a Trouble Funk live album, complete with crowd screams (the same idea the Bomb Squad would use to make It Takes A Nation Of Millions sound like a live album), tumbles over the 808, a sound effect from a track by disco drummer Cerrone accents the verses, while the single opening powerchord from AC/DC’s ‘Flick Of The Switch’ acts as the song’s heartbeat.

But the album isn’t just about the music. The character LL creates over the course of its 11 tracks is a perfect foil for Rubin’s beats – cocky, full of verbal dexterity, gifted, funny and likeable in spite of a degree of self-absorption you’d have found at best wearying if this was someone you’d ended up spending an evening with in a social context. Whether or not this was who LL really was back then is open to debate, but it was certainly the character he went on to inhabit. And it was a persona that didn’t only dominate rap for the duration of the golden age, it’s one that we see reflected in the inevitably more complicated creations hip hop artists today tend to people their songs and videos with. Remove Radio from rap history and, just as it’s difficult to imagine a Raising Hell, so it’s impossible to trace the lineage of a Kanye West. From the cheeky bravado of ‘That’s A Lie’ to the intense self-belief that underpins the attempted seduction in ‘I Can Give You More’, via ‘Dear Yvette’s cringe-inducing put-downs, the protagonist of Radio either codifies or prefigures most of the themes and personalities that were to dominate hip hop for years to come – for good and, on occasion, for ill.

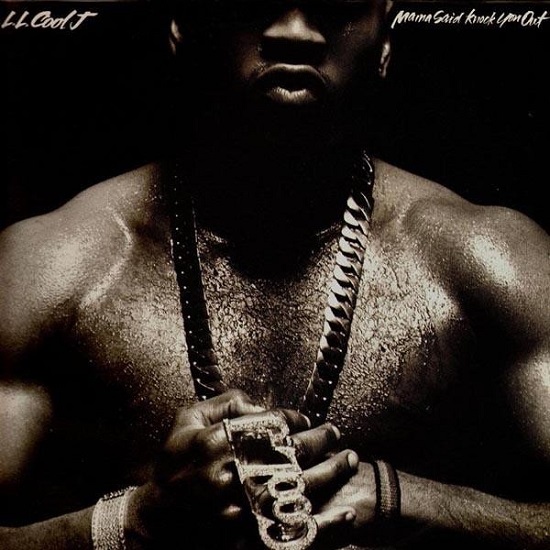

Five years later, and while much of that character-driven stuff remains the same, pretty much everything else has changed. Hip hop’s momentum seemed to increase in each of those years, with entire careers rising and falling in the interval between LL’s first and fourth albums. Indeed, the very fact he’d made it beyond a third LP put him in uncharted territory. Still barely into his 20s, LL was a veteran. And in a genre where fans appeared to place whatever was new or next above anything that had gone before; where a respect for history seemed entirely absent and past achievements irrelevant, the overall sense you get from Mama Said Knock You Out is of the boxing-ring-located Cool J – a picture the video from the title track gave us and which becomes the record’s dominant theme – coming out swinging after a spell on the ropes.

“Don’t call it a comeback,” he rapped at the opening of that track, and what’s perhaps most fascinating about this record is not that he should feel the need to start out by putting the naysayers and doom-mongers in their place, but that pretty much throughout the rap world, it was accepted by mid-1990 that LL had fallen so far from the pinnacle that this LP marked a make-or-break point for his career. That word “comeback” implies a long lay-off, yet it had been barely a year since his third LP, Walking With A Panther, and four albums in five years (plus one notable non-LP single) was hardly the slothful work rate of someone who had ever truly been away. Instead, to pick up the boxing theme the video and – to an extent – the album’s sleeve art encouraged us to hear the record through, LL was making a return to the ring after losing the belt.

He’d taken the title in ’85, just about clung on to it with Bigger And Deffer in ’87, but Panther was a flailing defence, a record that tried hard and could be argued to have succeeded with some misunderstood attempts at forging a new sound and style (‘I’m That Type Of Guy’s rapping James Bond routine; ‘Going Back To Cali’s louche declamations; the scintillating opening track ‘Droppin’ ‘Em’, two Meters samples ridden to perfection by one of the greatest exponents of the emcee’s art). The record sold well but came in for stinging criticism, not least for its several love songs – a “sin” for which LL had already been infamously punished, at Hammersmith Odeon in 1988, when he was bottled off on the first night of a three-night stint after bringing out a chaise longue to perform ‘I Need Love’, Bigger And Deffer‘s softcore ballad (and a record only a couple of years ahead of its time, as the emergence of Jodeci – a band that took LL’s gym-toned image and applied it to making street-soul aimed at a primarily female audience – would soon confirm). Never mind that all his records had included this kind of material: he was perceived to have fallen off. So whether we called it a comeback or not, Cool J had plenty to prove.

By 1990, Rubin was gone. Bigger And Deffer had been produced by Cool J and his friends the LA Posse, while Panther had found him experimenting with outside help amid a mainly self-contained set-up. Tellingly, though, in between albums two and three he’d made a single with Rick. ‘Going Back To Cali’ and its b-side, the brilliant ‘Jack The Ripper’, were recorded for the soundtrack album to the film version of the Brett Easton Ellis novel Less Than Zero, a record that also saw the first release of Public Enemy’s ‘Bring The Noise’. The a-side went on the album and was also included on Panther the following year – perhaps another factor in some of the lacklustre responses to that record: with rap moving at lightning pace, reliance on a year-old single to help beef up a supposedly “new” LP wasn’t all that convincing a move. It didn’t make it on to either the soundtrack album or the third LL LP (except as a bonus track on a Japanese-only cassette version), but ‘Jack The Ripper’ may have been the most important track Cool J released between Radio and Mama Said. It did enough on its own to sustain fans of his hardcore style through what were felt to be the pop-centric disappointments of the third LP, and gave heart to those who were worried that ‘I Need Love’ would take him ever further away from the sounds and styles he’d pioneered. The production from Rubin provides an interesting glimpse into how hip hop was changing: at roughly the mid-point between Radio‘s stripped-down, drum-machine-heavy beatscapes and the almost total reliance on looped samples that would come on Mama Said, ‘Jack The Ripper’ has feet in both sonic camps, Rubin’s trusty 808 underpinning loops from the Soul Searchers’ breakbeat classic ‘Ashley’s Roachclip’ and a selection of sampled stabs from previous LL classics enabling the still young star to call up his past hits to underline his currency.

But the self-produced nature of most of the preceding two albums clearly hadn’t ticked all the boxes for LL. So in another one of those ironies he was perhaps alluding to with that “don’t call it a comeback” opening, he went back to the formula that had served him so well on his debut, and opted to work with one producer for the whole of the fourth album. He chose Marley Marl, which might at first have appeared a curious decision but turned out to be inspired, and not just because of the quality of the album the two men managed to put together. Although the Queensbridge projects were a good 15 miles from the Farmers Boulevard neighbourhood in St Albans where Cool J was born and raised, both were in the borough of Queens – so Marley and LL had geography to help bind them. They’d both also been paired in hip hop fans’ minds for a few years anyway: in his epochal takedown of MC Shan, ‘South Bronx’, KRS-ONE had lobbed in disses of both Marley and LL, cementing their status as Queens rap icons in the process.

And here’s where we find the biggest surprise when going back after plenty of time’s distance to assess the relative merits of the two records: the more recent record sounds older, or perhaps more traditional. Rubin’s approach is redolent of futurism: by stripping hip hop down to its constituent elements then rebuilding songs out of tiny fragments of sound, he created something that was unmoored from its actual or thematic inspirations. Marley’s technique, rooted in extensive looped samples – he was the first producer ever to sample James Brown, and on Mama Said his layered loop style is at its most musical and free-flowing – has the effect of stressing the musicality of the source material. It’s funkier and smoother: and it’s not just on the proto-swingbeat of ‘Around The Way Girl’ where the music encourages LL to languorously drape his verses over the lush musical backdrops. Check the opening ‘The Boomin’ System’, where En Vogue samples joust with the James Brown licks they used as their own source material, as LL hymns the same block-rocking beat phenomenon Public Enemy wrote ‘Get the F— Outta Dodge’ about: this isn’t an experimental sound – it’s precision-tooled hip hop, where everyone involved has reached an evolved and deepened understanding of what their role is and how to make the music work.

That’s not to say that Mama Said lacks primacy, or that its sophistication comes with a degree of polish that would be offputting for hardcore heads – quite the opposite. Nor does that mean that hip hop’s core audience had become more conservative – though that may happen to be true too. The title track is enhanced by Marley’s musicality (though credit for that song is also shared to one of LL’s two regular DJs, Bobcat): the pairing of a sample from the oft-overlooked first Sly & the Family Stone album with an exclamation from Eddie Bo and drums that ought to have been as hackneyed even in 1990 as ‘Funky Drummer’ and ‘Sing A Simple Song’ is nothing short of exhilarating. The track remains among the greatest moments in the discographies of all involved, and it’s one of LL’s best three or four singles – but it’s not the best track on the album. That honour, at least as far as this pair of ears is concerned, goes to ‘Eat Em Up L Chill’, in which Marley slows down a Charles Wright sample and welds it to the drums from The Five Stairsteps’ ‘Don’t Change Your Love’ (later to return to active service in Naughty By Nature’s ‘Hip Hop Hooray’), to provide the perfect base on which L builds a timeless brag. The music alone was influential far beyond hip hop’s borders – Tricky used it for the heart of his debut single, ‘Aftermath’, and it also formed the basis of DJ Zinc’s ‘Super Sharp Shooter’ (it’s possible either could have got to the same sound by reverse-engineering Marley’s beat and re-sampling the same sources: but it’s unlikely they would bother to do that merely to recreate Marley’s finished phrasing, and even if they did, it would have constituted a cover-version of his idea).

Throughout the album L is on fine form. The humour that on earlier records (and indeed, more than a few later ones) can sometimes seem forced or gauche here feels about as sprightly and well crafted as the battle rhymes and cocksure boasts. There’s something slickly discomfiting about his seduction hustle – ‘Mr Good Bar’, as fizzing a concoction as anything in Marley’s oeuvre with All The People’s ‘Cramp Your Style’ propelling a haze of ESG siren-guitar, features a creepy lyric in which you get the feeling that LL isn’t so much trying to win the heart of the woman he’s addressing as seeking to demonstrate his superiority to her current boyfriend by snatching her away from him – but, for the most part, the lazy sexism that led Sonic Youth to single him out for censure (‘Kool Thing’ is about him: Kim Gordon had interviewed LL for Spin and came away from the encounter dismayed at some of his ideas about sexual politics. She has since pointed to the self-critiquing in the song and suggested that its humour, a great deal of which is at Sonic Youth’s and their circle’s expense, was missed by many listeners) is no longer pushed quite so frequently to the forefront. And in the closing ‘The Power Of God’ there’s a “message” song better than any he had attempted thus far. On top of this, the album’s pre-eminent battle track – ‘To Da Break Of Dawn’, in which he goes in on long-term nemesis Kool Moe Dee, launches in on MC Hammer in verse two, and responds to Ice-T’s perceived slight in the opening of his ‘I’m Your Pusher’ in the gloriously irreverent final stanza – is among the greatest examples of the type. Its impact was considerable, too: Ice Cube got the “no vaseline” idea from here, and Premier scratched a line from it to make the hook for Gang Starr’s ‘Who’s Gonna Take The Weight’. (And if you want an example of how battle raps obey rather different rules to other songs, try listening to the track, in which a macho rapper seeks to belittle a competitor by implying that he whacks off to a picture of said rival’s wife on an album cover, and come up with a more cogent or adult a response than immature guffaws.)

But it’s on ‘Eat Em Up’ where we get to hear LL at the top of his game as an emcee. Every part of that unique combination of voice, flair for wordplay and an indomitable self-belief is operating at maximum over the three verses, but the song reaches an unmatched high towards the end. The first verse sets the fire burning with some alliteration and internal rhymes, delivered with an eager, almost puppyish bounce (“Rhyme sayer, and I’m here to lay a load/ so watch the player when he’s playin’ in player mode”) but the song opens with lines that add an atmosphere of blasted desolation to the battlezone: “Hold your nose: dead bodies are around/ I leave scratch marks under the tears of a clown”. Verse two adds to that sense that the beat helps build, of LL as the last gunslinger left standing as hip hop’s sharp-shooters saddle up and leave the frontier behind: “So creative and witty and outstandin’/ and I’ll be demandin’ that you’re abandoned/ in the desert or a wild west town”. But it’s the final verse that I think I’d choose if anyone ever asked for a single stanza as an explanation of what LL could do better than anyone else. After an opening where he advises an unnamed rapping adversary not to bother, he ends up incorporating a sneeze and a “God bless you” response into the meticulous takedown before ending with a description of his cartoonish method that’s as clever and amusing as only the greatest battle raps can manage.

On both albums you can understand both why he would call himself “Uncle L – future of the funk”, and why anyone would take him at his word. Hip hop had changed, and LL had responded by digging deeper, working harder, and getting better at giving the growing audience what they never knew they wanted. There was more to come, before pop stardom, movies and sitcoms demanded enough of his attention that LL seemed to largely lose interest in being among rap’s leading stylists and innovators. But there’s no arguing with his achievements at the start of his career, and no point trying to deny the quality and the appeal of these two records.