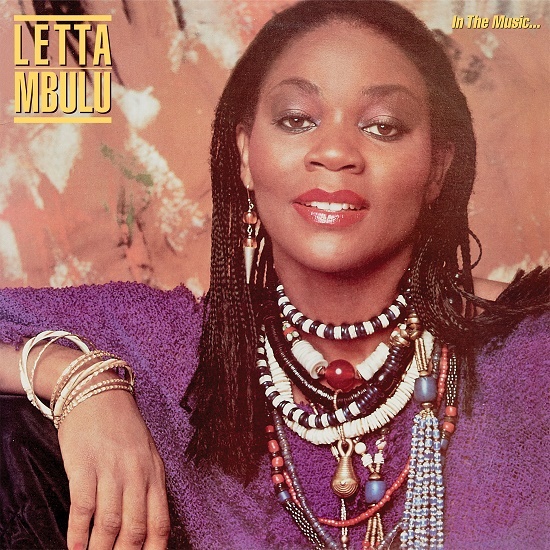

When the South African singer Letta Mbulu released In The Music The Village Never Ends, her motivations went beyond those of many of her disco/soul associates. On the surface, the album’s simple danceability seems to evoke the fun, easy-loving freedom of ‘80s America. Prince and early Michael Jackson influences ooze through on lead single ‘Nomalizo’, while the cool swagger of Mbulu’s vocals radiate an irresistible warmth. Already an established name by becoming Quincy Jones’ go-to African voice, Mbulu chose to pitch beyond her adopted US home and create an album that would be heard throughout Africa. The result failed to match its ambition in terms of sales. Instead, the forgotten nature of In The Music The Village Never Ends highlights the plight faced by a South African musician in 1983; flourish in exile where people are keen to hear your cause, or risk heavy censorship speaking to the people you truly represent.

Re-released now thanks to Be With Records, In The Music The Village Never Ends is valuable both for its musical sweetness and its bold contextual statement. Mbulu had been in exile since 1965, and the album is a self-reflection on the larger South African cause from a singer no longer fazed by the heady possibilities the American music industry presented. “It makes me feel great that it’s now being appreciated by a Western audience”, she says of the re-release. “I was approached out of nowhere, and I was like, ‘Wow! That thing was recorded in 1983!’ I couldn’t believe it. I still don’t believe it.” I speak to Mbulu at home in Johannesburg, where she’s been living since 1997.

How’s the album been surviving up until now?

Letta Mbulu: It first got released when I was in the States. It did pretty good for the time, but all music was limited by the fact that South Africa was not stable. It was hard for musicians to have any authority. I was distributing through a company called Moonshine in South Africa, who worked a lot with black artists. I was releasing so many albums at that time I don’t remember how that one did. I don’t think a lot of people remember the album in South Africa today.

Did it stand out as your best work?

LM: It could’ve been if we’d had a big company who were willing to work with it. That album was targeted at Africa, because I had come to realise that most of my material I was recording in the US was not reaching the continent. In the States, people don’t know much about In The Music The Village Never Ends.

When I talk about Africa I mean the whole continent outside of South Africa, because a lot of my albums that came in were banned in South Africa. I’m not sure of the exact songs or numbers, but my output was very restricted. In The Music The Village Never Ends was a social commentary, and this was not welcomed at the time. So now when radio stations play my old music, people say, ‘Oh hey, a new song.’ I’m fascinated by why this album has been chosen for re-release, and I’m excited because everyone involved worked so hard on it. The effort put in makes it stand out for me in my catalogue.

What where your motivations?

LM: I just wanted to sing, and I didn’t want my music to be unique to the US. I wanted Africans to hear it and know that South African music was still alive. I always knew I was going to come home at some point, and I wanted to have a name for myself. I knew South Africa was going to change; you can’t keep people down forever. It’s unnatural. Somehow something had to crack, and it did.

Who were the best South African musicians from that period?

LM: There were many great artists at the time, but most of them didn’t get the opportunities that we had by leaving the country. Individual names would be meaningless. Some of them ended up in the US and had careers, but going into exile was the only way to achieve this. It was the only way to get your music played. Graceland was recorded in South Africa and was successful, but a big name like Paul Simon had to come in to make this possible otherwise it wouldn’t have worked.

How did you find living in exile?

LM: It had a positive side, because I was able to do what I loved to do which was singing. I was able to work and meet a lot of people. Being in exile set me up with Quincy Jones, who got me to sing the theme song to the Roots TV series, ‘Many Rains Ago’. Later I contributed to the Michael Jackson track ‘Liberian Girl’. America helped me to grow as a performer.

How did your cameo on ‘Liberian Girl’ come about?

LM: I was playing a concert in Senegal, and I got a call from my husband saying Quincy was doing a song and wanted someone who could sing in Swahili. I don’t speak Swahili, but I was his go-to African voice and I had a friend from Kenya who was able to help me write the words. It went something like ‘Nakupenda’, meaning ‘I love you’. And I chanted ‘ah-ah-ah-ah’ at the end because I knew what Michael liked. He was very fascinated by me coming from Africa, but he was quite shy. It was an honour that he chose me – you couldn’t get bigger than that.

How was your music received in the US?

LM: I think I brought something new and exciting. America is good like that- if you come along with something a little different, they’ll package it. It was revealing for them to see what Africans and South Africans could do musically. Miriam Makeba, Hugh Masekela and Dollar Brand [now known as Abdullah Ibrahim] were all working in America, so the potential of South African music was clear.

How active were you in America’s civil rights movement?

LM: Yeah, I went through all that. It felt like being back home! I went through riots in Los Angeles; you know, it really reminded me of South Africa. The civil rights movement helped me understand that these problems were universal. I felt comfortable that I could build an audience who welcomed my stories, and who wanted to know more about what I was singing about and why I was in exile. This outsider’s perspective really helped me understand South African politics better.

What was it like coming home?

LM: Mandela was released in 1990, and I came back in 1991 before settling permanently in Johannesburg in 1997. It was beautiful to come home. Really wonderful. There are big problems in South Africa still but you know what, hey, this is my home. And I need to accept that with the problems. Jo’burg had grown tremendously from the city I remembered as a kid, and it had become rough. It’s better now 20 years on. I listen a lot to the incredible young artists who are coming through, which is something that just wasn’t possible during Apartheid. That’s the way I learn.

In The Music The Village Never Ends is released by Be With Records