Someone once asked me what I did when I listened to music, and, although simple enough, I stalled to answer the question. By clearly separating ‘listening’ from ‘doing’ the affable enquiry sent out a wave of non-musical dissonance that disrupted any chance I had of forming a satisfactory answer. In the end I think I said something like, "I don’t do anything,” which got a pitying, slightly weary look like you might give someone serially unsuccessful at dating. Feeling like I needed to positively qualify my terse response I added, “Well, I sit there like I’m watching a film, but without the images," but my inquirer had already lost interest and swiftly changed the subject. The question has haunted me since, though, making me wonder what others do when listening to music without utilising it in other activities and how they might answer the question.

A quick straw poll around the Rum Music Library’s various departments added little to my quest – some sought psychedelic soundtracks to recreational drug experiences or the comfort blanket of ambient music to help reduce the tensions of modern life, while others were simply rapt in memory – re-drafting volumes of internal autobiographies to nostalgic cues. Even the behavioural psychology unit’s recent video footage of people’s home listening habits disappointed as the regularly flitting eyes of the majority suggested a simultaneous stimulation from online browsing, relegating the musical matter to the backs of their minds (reminding of Will Self’s suggestion when ringing the death knell of the novel, that “the work of the imagination, which needs must be fanciful, was at a few keystrokes reduced to factualism.”)

It doesn’t help that composers rarely provide guidance for listening as much as they do contextual descriptions of concepts and influences; playback instructions almost always limited to volume (and a maximum one at that). So, once again we find ourselves alone with just a pair of ears, a playback system and a range of wayward releases in which to rummage. Maybe the only instruction we need is the work itself: by surrendering the senses to the sound each piece can become a score for the listener, to be ‘read’ and responded to, letting it in to interfere with or obliterate internal dialogues, and inform the next immersion.

Francisco Lòpez – 1980-82

(Nowhere Worldwide)

The Spanish sound artist Francisco Lòpez encourages a mode of listening by reduction: offering audiences a blindfold to help focus on his sounds without visual interference, and avoiding the semantic signals risked by concepts or track titles. This Schaefferian faith that we can transcend meaning and, instead, attend solely to sound’s inherent sensual qualities is, on the evidence of this release, something Lòpez has now upheld for over 35 years.

1980-82 was recorded using techniques determined by the affordable technology of the time – Walkman recorders and cheap cassette players – their usually indelible contributions of hum and hiss open the disk but are quickly cut as we’re enveloped in the deep and rich sonic qualities we’ve come to expect from the artist. Lòpez edits each piece and arranges the album as a whole to dip his listeners in and out of a sequence of contrasting sensations, from the opening’s murmurating confusion of womb-like low end and nebulous high end, through searing, speedy showers of sonic scree, and into a war of attrition between elemental and organic noises.

Then, on first listen, the final, longest piece seems fairly constant – its small, low rumble, poised with suspense, but uneventful. However, a second listen reveals the speakers’ woofers restlessly throbbing as inaudible subsonic material visibly filled the room.

There is a keenness Lòpez consistently inspires throughout his work, a rewarding reengineering of our sensibilities toward sound, regardless of source material or the technology he uses. Indeed, talking about the cassette technology of the time in the brief and rare sleevenotes that accompany this release he observes, "With hindsight, this limitation turned out to be a great advantage and an important lesson that has remained vividly present for me until today: the most essential tools are spiritual, not technical."

Heitor Alvelos – Faith

(Touch)

The two times I’ve had the pleasure of witnessing Heitor Alvelos’ actions was when he performed a 39 second set as Autodigest at Touch’s 30th birthday event and at The Tapeworm’s fifth anniversary celebrations where he was wrapping the audience in spools of ferric oxide. The former saw him compressing Touch’s entire 30 year output into a short, sharp blast and the latter was in tandem to handing out the 73rd Tapeworm release, suitably titled Free Tape whose box contained just that, a jumbled mess of tape in tribute to the memory of the Walkman’s mastications. But for Faith the Portuguese artist and academic researcher in design, media and culture, uses his own name to author a more solemn and spiritual work. Described as “autobiographical” and an "acknowledgment of the deeply intimate as a regenerative force: fragility, humility, desolation, trauma". Faith’s 11 tracks are formed of field recordings and “audio irregularities” from the past four decades. But, whereas autobiographies tend to use words, Alvelos deliberately chooses deep, contemplative layers of suspended sonic qualities that bypass the clumsier negotiations of speech and text.

Flowing as a single piece rather than 12 vignettes, it largely consists of what could be described as a series of auras (words like ‘drone’, as ever, feeling too limited and one dimensional). The opening piece, ‘Errant’ could be a short recording from within an air conditioner, while longer pieces such as ‘Pseudoself’ and ‘The Way Of The Malamat’ are more expansive like being up in the troposphere travelling through a cloud’s formation or at the bottom of a deep, rumbling chasm. Each has a increasing presence that develops steadily, commanding a powerful poise like the otherwise stolid monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Of course, with sounds so abstracted their literal significance is only known to the composer, but such is the refined quality of their passage the emotive essence of Alvelos’ Faith is both intensely and tenderly clear.

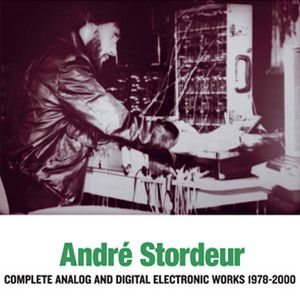

André Stordeur – Complete Analog And Digital Electronic Works 1978-2000

(Sub Rosa)

The Belgian electronic music composer André Stordeur wanted to find "an alternative to the so-called cosmic electronic music…" and instead focus on the “human and intimate… fears and obsessions connected with our daily lives” according to the sleevenotes he provided on his debut, and so far only, album, 18 Days, released by Igloo in 1979.

Rescued from obscurity on the first in this three disc archival release from Sub Rosa, 18 Days‘ showcases three pieces per side of pure modular synthesis. It’s a timely reissue given the current levels of interest in wiring all manner of synth modules together to form unique electronic compositions ungoverned by a computer interface (although Stordeur experimented with this too). ‘To You’s tender swells of piano and strings is downright romantic (not a word you’ll find that often in this column), as if laying bare fragile, loving emotions. ‘Memories’ on the other hand is worried and brooding, with long buzzing tones bending in and out of each other not unlike the contemporaneous outputs of Chris Carter’s Gristleizer. Stordeur even attempts a sonic seduction of sorts on ‘Aphrodisiac’ with electronic splodges and brassy blasts wandering around together in a lusty quest – its rude and raw representation of our carnal urges has a frankness that most other attempts at musical love-making lack in their peacocky persuasions.

The second disc features two long form works created in the early eighties. ‘Oh Well’, another plain-speaking title that Stordeur admits was recorded "at the time [of] a painful divorce," is an eight channel opus for Serge synthesisers, a brand he would stick with and ultimately work for as a consultant. It is a restless and discordant state where percussive passages, perhaps drawing on Stordeur’s earliest musical experiences as a drummer in a modern jazz quintet, shuffle the listener through an often manic parade of throbs, bends, bubbles and showers until eventually crashing, only to exit on a bizarre carnival-esque tune.

Created the following year while studying at IRCAM, ‘Chant10A’, named after the software the institution afforded him, has over 1,000 virtual oscillators form a rich, dream-like journey in slow motion through watery depths, icy plains and cloudy heights. While vastly different in temperament and tone, both ‘Oh Well’ and ‘Chant10A’ bear the same thirst for experimentation, urging the machines to become as versatile in articulating emotions as orchestras had been doing for over 300 years.

The third disc, although a little less experimental, displays this same intent to validate electronics into the history of composition, but goes back even further into medieval Indian music. ‘Drone’ mimics the long-necked ululations of the tanpura, its rich, longform tones rise and fall mesmerically; while ‘Raga’, with accelerating tabla sounds nimbly knitting the extending strings, is so authentic as to belie its synthetic source.

The variety of sonic experiences found across this epic release of pure electronics, from modern abstractions from the subconscious to the modes of ancient tradition, is refreshing as much as it is fascinating.

Marinos Koutsomichalis – Ereignis

(Holotype Editions)

Serge modulations are also the expressive choice on this latest physical release from Crete-based artist Marinos Koutsomichalis. Board member of the Xenakis-founded Contemporary Music Research Center (CMRC-KSYME), the outputs of his intense R&D activities into electronic sound and how it is perceived is more often exhibited or performed than captured on disk. Ereignis started life as a series of performances between 2012 and 2014 where Koutsomichalis steered the modular synth into unpredictable territories until it began ‘composing’ by itself.

Like Stordeur’s experiments the results offer fresh sonic perspectives on the more metaphysical side of the street, but where Stordeur challenged himself with describing the “human and intimate”, Ereignis possibly presents something much more terrifying: its concept making the composer extinct, its results sounding like entropy in effect.

Recorded at EMS in Stockholm, it begins with a flailing and complaining, wailing and fizzing tone as if protesting against its very birth. But exhaustion repeatedly sets in only for the emissions’ energy levels to get re-set and work themselves up into more complex phases. With each successive refresh increasing evidence of fatigue is displayed, the tones become more corrupted, their stuttering escalates, or the force of their trajectory reduces. It’s a bleak portrait of the futility of a weakening state attempting to regain its former strength. By the time we reach the second side, the stubborn crumbling continues to falter with doomed attempts to rise and surge like a slow death rattle of an animal gone to ground. Ereignis is like conceptual art created by machines to taunt us with our own mortality.

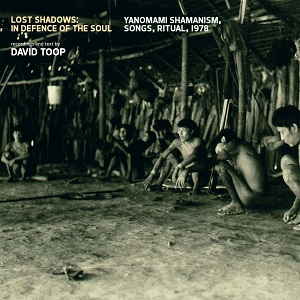

David Toop – Yanomami Shamanism, Songs, Ritual, 1978 / Lost Shadows In Defence Of The Soul

(Sub Rosa)

Both human and intimate, it’s difficult to know how to listen to this much expanded reissue of David Toop’s recordings of the Yanomami villagers who reside in the Amazon rainforest. Originally released in 1980 as Hekura – Yanomamo Shamanism From Southern Venezuela on his own Quartz Publications (thanks to funding from Robert Wyatt and Evan Parker) it included just two excerpts: ‘Dayari-Teri – Group Healing’ documents six shamans drawing out malevolent entities from their community and ‘Torokoiwa – Solo Shaman’ who agreed to chant specifically for Toop’s recorder. As well as providing more of each recording session this reissue also includes additional events and encounters, such as songs performed to succeed in hunting or to bring on rainfall.

But the difficulty in consuming this exotic artefact, albeit a welcome one, is whether to approach it as documentary, sound object or signifier. As a documentary it is hard not to notice the casual chatter that goes on in the background, often including children, as the shamans dramatically chant, cough and spit a series of guttural and anguished, loose rhythmic phrases. The contrast between the fierce shouts and growls of the performer and the seemingly inattentive audience confounds expectations, bringing it closer to an A&E waiting room than a reverent church service. As sound objects, certainly an unintended output, the recordings are captivating, especially over a long period of time as ones ears adjust to a wide family of terrific vocal textures and combinations. But one can’t help feeling there is also a sign in here somewhere – the zest, determination and confidence heard in the chants perhaps forming a persuasive invitation to discard long-held inferences of Western logic and embrace a more animistic attitude.

As if to emphasise this, Toop concludes each remarkable disc with the non-human night time sounds of insects, birds and moths; the insects’ dense canopy of chirruping, punctuated by birds’ whistles and whoops and the occasional thrum of fluttering moths casts its own spell. Lost Shadows… is an insightful document, a sensual sojourn and a signpost into areas beyond our understanding.

alva.noto – xerrox vol. 3

(Raster Noton)

The work of Germany’s Carsten Nicolai can seem intimidating as much for the industrious quantity of projects as for their academic qualities often poised in the interceding areas of sound and vision. But whereas his exhibited work can be immediate and self-evident in describing relationships between the senses – from patterns on the surface of milk created by a specific sonic frequency or unique sound events triggered by the formation of snow crystals – his recorded work can feel initially clinical and sterile. Just like the installations, the sounds are often based on controlled processes that generate patterns whose repetitions reveal idiosyncrasies amid the synchrony. The thematic process for his Xerrox series is, unsurprisingly, copying: “everyday sounds” are apparently transformed through multiple duplications to become ‘new’ sounds in themselves. Instead of putting processed patterns to the fore, the results tend to be an interplay of emotive musical themes and almost organic textures with this third volume inspired by “childhood film memories”. Most notably Nicolai cites Tarkovsky’s Solaris whose vast, slowly orbiting, lonely space station filled with ghosts is as good a description as any for the sentimental sonic fare on this disk.

Perhaps the most affecting sound on Xerrox Vol. 3 is on ‘Helm Transphaser’: placed amidst the omnipresent deep engine underpinning slow, grandiose chords there lies what sounds like the flutter of a moth. Rendered in high definition it plays with scale by comparing a spacecraft monitoring a star to a moth’s equally curious and dangerous fascination for a candle flame. While still retaining a patina of process, Xerrox Vol. 3 feels more human than other alva.noto releases, subtitled “towards space” it succeeds in evoking a lonely quest into the vast ether – can we expect future volumes to head into deep space or onto alien worlds even?

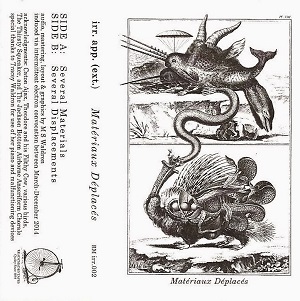

irr. app. (ext.) – Matériaux Déplacés

At Jennie Richie – GVVVR

Balkh – Confounding Interest / Hüsker Dü

Crank Sturgeon – Crank Sturgeon Has A Meat Jacket

Vertonen – Cast Away

(Readymades Tapes)

Something wicked this way comes as the carny that is Readymades Tapes once more arrives in town with a batch of five sonic sideshows to whet your whistle. While each artist amplifies their own idiosyncrasies to produce delights the like of which you’ll never have heard before, they share a keenness for creating perverse oddities to shock or downright traumatise the curious.

Matt Waldron says about his latest irr. app. (ext.) release "Trying to write about irr. app. (ext.) is like trying to make a building out of dance" and he’s not kidding, I’ve tried and failed several times in the past. Plainly put, to listen to irr. app. (ext.) is to be messed with, but Waldron’s a fairground barker you can trust and, as his latest two curios on Matériaux Déplacés attest, his work is always rewarding such is his singular strangeness. Side A folds and inverts a world around you Inception-style as dizzy spells of piano trigger all manner of movements, but this merely limbers the listener for the main attraction. Instead of generously serving up another complex collage, side B is perhaps one of Waldron’s most intense, visceral pieces, albeit still twisted. A rich, ribbed road drill grows ominously and slowly as shivering waves brush the listener only to be abruptly cut to reveal an asylum of delirious voices, some human, some not, hungrily laughing, fervently gobbling, helplessly wheezing. The tape ends suddenly, feeling like you’ve been kicked out of the tent with no idea of what you’ve just witnessed, but a firm feeling that you’re not the same person who entered the attraction.

GVVVR is a new cut from irr. app. (ext.) associates At Jennie Richie (a duo from Ballard, Seattle) this time in collaboration with Mason Jones (of San Francisco’s Numinous Eye and Charnel Music label). It is somehow inspired by driving on North America’s Interstate 5, but feels more of a malfunctioning ghost train ride than a road trip. Stalled for what seems like an age with a high pitched scintillating tone, its glassy brightness ideally requiring the audio equivalent of hands to hide behind, it finally lurches into movement with glitchy bursts. The uneven ride is briefly sorted out by a low slung rhythm, nimbly demonstrating the reliably propulsive jump-lead effect of beats. The drums somehow sew the nightmare noises together to form a skewed theme, proud and brash, before devolving into explosions and crowd noise as the fairground is destroyed. As ever, the work is both playful and experimental with a sense of destructive malevolence that belies the duo’s nom de plumes of Happiness and Forever.

The duo of California’s Eriijk Rêssler and Doriandra Smith showcase their live layered loop-based attractions on this, their second release for Readymades Tapes. Describing their process as "snapshots of remembered moments that have only just occurred", the repetitive cycles of Side A’s didgeridoo-like tones charm with their mantric ritual – hypnotic, heady and seductive. The loping, evenly rhythmic pace brings it a bit closer to rock music than the rest of this batch giving it an accessible edge that leaves you wanting more. The flip is freakier spinning looped voices – speech fragments, operatic old time radio and religious intonations – into a phantasmic soup.

For his seventy-somethingth release since 1993 Maine’s Matt Anderson donates two maniacal cacophonies to Readymades. Operating his tape machines like a self-indulgent lead guitarist, rapidly switching, cutting and bending, the results are maddening in their freneticism. ‘Husopathy’ sounds like it’s produced by a hybrid cassette player/photocopier fed by random YouTube videoes as it churns out a mutliverse of repetitive fragments. The gleefully-played delirium could easily represent a time-lapsed survey of a day-in-the-life of a pestered brain, its snippets of voices, grunts, bleats and brief bursts of music emphasising increasing levels of mental pollution. ‘Husography’ follows a similar patter but uses recordings of squealing, grunting and straining, suggesting a gross, pressurised struggle before turning feral with ripping and bustling noise.

‘To Jsi Ty, Můj Drahý’, takes the first side of Vertonen’s eerie Cast Away, combining various elements relating to a mysterious case of kidnapping and murder in the artist’s hometown of Chicago in 1911. The release only states that the piece includes recordings made at Elsie Paroubeck’s grave, but a Wikipedia search reveals the longer story of the missing five year old whose body was eventually found in the city’s canal believed to have been strangled. The distressing tale makes sense of Vertonen’s choice of additions to the everyday ambience of the graveyard: an organ grinder solemnly plays linking to the last reported sighting of Elsie, apparently in awe of such a street entertainer as he moved his pitch with her and her cousins in tow; and incorporating the National Anthem of the Czech Republic refers to the nationality of Elsie’s immigrant parents. These layers intertwine and decompose under a title that translates as "Is that you my dear?" to form a grisly sonic séance.

The second side’s ‘Particulates’ is a more engaging listen, but still retains a funereal feel. Suspending a restless swarm of distortion in its odd atmosphere before switching to a heavenly yet solemn exit, the work for "tape, turntable, shortwave, electronics" acts as a post-rational requiem for the spirit potentially disturbed by Cast Away‘s first side.

Hilde Marie Holsen – Ask

(Hubro)

It kind of spoils the spell to reveal Ask, the debut album from Oslo’s Hilde Marie Holsen, as being wholly formed of live improvised processed trumpet. Recorded at the Norwegian Academy of Music, the album displays both an intensity and charm far beyond the image of a trumpet and laptop. Opening with brief, startling layers of engine-like textures that harden like the mineral (Ruby) its title references, the first side continues with two longer pieces also named after minerals as if to suggest some kind of geologic process. Throughout, the trumpet’s lead is nested in a transformative process that expands but never intrudes. ‘Plagioklas’ pairs a solemn, slow horn theme with a hopeful bed of pleading treated tones, as wisps of breath circle until an effervescent burst, neither brass nor electronic, climaxes. ‘Muskovitt’ feels even lonelier, its spare, cool cries receiving nothing in reply apart from tender, subtle low end ambience, while the title track follows the same strategy but turns the preceding loneliness around with a sense of wonder. Its lead melody no longer needy, its accompaniments just small movements and distant tones, they take time to inspire each other into exploring their emergent sound world.

Perhaps not as much geologic as alchemical, there’s an uncanny dimension Holsen somehow sculpts throughout Ask‘s 45 minutes – kind of blue, but kind of other – that tenderly and masterfully attends to both melodic and textural dimensions to form a sublime sensual sound.

Chra – Empty Airport

(Editions Mego)

Before making a sound, Empty Airport‘s title deftly self-selects a dystopian lens through which to focus on this second solo album from Vienna’s Christina Nemec. A vast, modern interzone conspicuously abandoned feels like an opening scene from a JG Ballard novel, and the moods and movements Nevec evokes here across 11 tracks certainly promote a similar unnerving and dramatic displacement. Roaring static, buzzing electrics, dripping cisterns and rusting machines all pollute the haunted air as the listener is drawn into a stealthy survey for signs of life. Urged forward by rich, deep, bass pulses, the industrial dub of nineties Birmingham (such as Godflesh and Scorn) – a city of many abandoned buildings and warehouses – comes to mind, along with the dread electronics of Pan Sonic. But by dropping almost entirely the club-bound beats found across her debut, Chra creates more of a sensuous experience of decay than a grim sample-laden groove. Her Empty Airport is built from resonant ruins of rhythmic structure on which a monochromatic debris field grows possessing the kind of bleak, perverse beauty to that found in Jane and Louise Wilson’s photographs of eroding concrete defences from World War II or Paul Nash’s surreal, unpopulated landscapes.

Shampoo Boy – Crack

(Blackest Ever Black)

Nemec’s rich bass is contrasted with Christian Schachinger’s scintillating guitar and Peter Rehberg’s swarming electronics in Shampoo Boy. Friends for over 30 years, the Viennese trio’s latest free improv jams are once again edited into compelling and commanding nebulous shapes. Following on from 2013’s Licht, whose energies evoked the glows and sparks of flames or molten heat, the pooled sounds on Crack are also primarily atmospheric but, with a seemingly injurious theme across its terse titles (translating as Crack, Split and Fracture), it can also seem somewhat psychopathic. ‘Spalt’ has a rough, dirty synth that, combined with its title, projects images of flies increasingly creeping through a gap, its underscore of spiralling textures suggestive of the more disorientating manoeuvres of both black metal and kosmische music before all reduces to an insect shuffle. ‘Riss’ is more ritualistic as a dark bass intones in an ominous air of sibilant electronics while eldritch guitar sounds circle the summoning space. Side two is taken up by the three part ‘Bruch’, a body horror theme if ever there was one, that follows a sickened, staggering pace as it slashes of over-crusted guitars bear a red-misted anger. Punctured by feedback and whipped by mutating synths, if anyone uses this incredibly evocative music as the background to an activity, I really don’t want to know what they’re up to.