You see that figure over there with the fuzzy ponytail poking out from under a Greek fisherman’s cap, his jeans torn at the knees, his ankle-length, grey raincoat rescued from a charity shop’s neglected racks? That’s me, the music editor of Exeter University’s The Third Degree magazine, an expensively educated, former private schoolboy desperately looking for a way in life that won’t lead him to join the army, like his father, or to work in the city, like many of the people around him plan to.

See that guy, seated at the same wobbly coffee table, scanning the Student Guild Coffee Shop from beneath a wild mop of bleached hair for an excuse to stand up and leave? That’s Thom Yorke, who’s too well brought up simply to walk away. He’s already living my dream, I’m sure, but he’s not especially happy. It isn’t my fault: his band’s first record has been delayed by a couple of weeks. His label has forgotten to ‘sell it in’, the name given to the process of persuading shops to take stock of forthcoming releases. His gripes seem wholly justifiable.

It’s May 1992 – just under three years before Radiohead will release The Bends. The Drill EP, which is currently languishing in EMI’s warehouses, is the group’s debut release, though they’ve been knocking around since 1985, when they formed – under the unpromising name of On A Friday – within the centuries-old grounds of Abingdon School, outside Oxford, where Yorke and his bandmates were boarders. I studied three and a half miles down the road at an even grander establishment – or at least that’s how many of its staff and pupils haughtily thought of it – but this isn’t something we’ve discussed. We’ve not discussed much, in fact: I barely know the man.

By now, Yorke has left Exeter University and returned to live in Oxford. I, meanwhile, still have over a year left to go. Nonetheless, we share a couple of friends. There’s Paul, whose hair showers down his to his beltline and who books shows for the students, generously ensuring I’m on the guest list any time I want. In later life he’ll teach special needs kids, and any his wilder tendencies will be indulged instead on a vintage motorbike. Then there’s Shack, the dreadlocked individual behind technology-loving duo Flickernoise. He’ll go on to enjoy a career as a musician and DJ – under various names, including Lunatic Calm and Elite Force – but he and Yorke used to play in Headless Chickens, an indie punk act featuring Thom on guitar and backing vocals. You can hear Thom on their only recorded track, ‘I Don’t Want To Go To Woodstock’, part of a showcase 7" for local label Hometown Atrocities. It features two other woefully named acts, Jackson Penis and Beaver Patrol, alongside the rather more prosaic Mad At The Sun. If you really care enough, copies are available these days for about £75.

I try to placate Yorke’s concerns about their debut, informing him I’ve given it a great review, like I expect him to care what I think. I’ve described it as "a storming opener to their career, a noisy guitar affair reminiscent of The Catherine Wheel", but I don’t tell him I’ve given Kitchens Of Distinction’s ‘Breathing Fear’ and Suede’s ‘The Drowners’ joint Single Of The Month status. Nonetheless, I’m excited to see the band perform, and I’m particularly keen to see if he can replicate that fifteen second wail at the end of ‘Prove Yourself’, the lead track, though I don’t articulate that last thought out loud. I’m actually far too nervous: Yorke’s the first person I’ve ever met whose band has signed a deal.

As a student music critic, I’ve met other musicians, of course, but they were already with a label by the time our paths met. Yorke, on the other hand, was a DJ at the university venue, The Lemon Grove, up till the end of last summer, and Paul reckons he’s probably the best they’ve ever worked with. Yorke would entertain my friends and me on Friday nights as we sank snakebites and black until our limbs were loose enough to dance. Sometimes I’d make requests – The Stone Roses, The KLF, maybe Happy Mondays – and I far preferred Yorke’s indie playlists to the club-fixated Saturday nights, which were hosted by Felix Buxton, later of Basement Jaxx. Back then, Exeter’s Oxbridge rejects were far more privileged than they could ever have guessed, for many more reasons than they ever realised.

This encounter is the first time Yorke and I have talked for more than a moment or two over the record decks. Despite not really knowing him, I’ve still got this nagging feeling. He seems focussed and self-aware, his bearing suggestive of a man confident that his choices will prove worthwhile. The music I’ve heard has helped: the Drill EP isn’t an exactly stellar start to their career, but it’s a convincing debut. It sounds like it was recorded in a budget-priced, provincial studio by a band excited at the possibilities newly available to them: the vocals distorted and artfully buried in the mix, the guitars raw and fluid, the bass lines imaginative, the snare drums tightly tuned. In the flesh, too, Yorke is just like a budding rock star should be, and though his mildly aloof demeanour makes me feel a little uncomfortable, it’s something I can’t resent, the existence of our mutual acquaintances making me feel quietly loyal to him. In years to come, I like to think, I’ll be able to tell people I used to have coffee with Radiohead’s Thom E. Yorke.

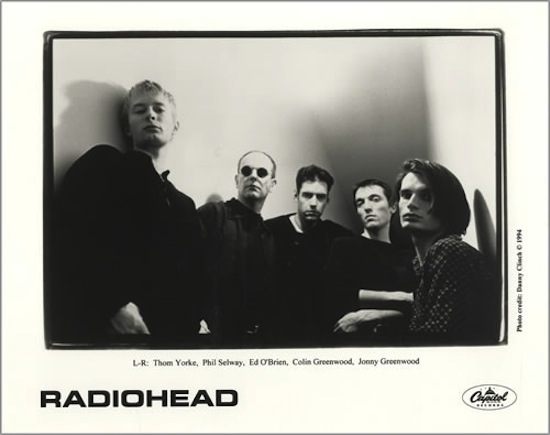

Six months or so later, I’m behaving like the worst kind of student, shitfaced, most likely stoned and, more worryingly, high on a sense of my own importance. A white label of ‘Creep’ landed on my doormat only a few weeks earlier, and it’s the most exciting thing I’ve heard in a while. This time I honour Radiohead with a Single Of The Month – "This has to be one of the best pieces of rock since Everest," I write, oblivious to how this will make me wince in my future – and now they’re playing at the university. I get to hang in the dressing room for a little while with a couple of friends, enjoying what I like to think of as Thom’s victorious homecoming. These companions include one of my more glamorous associates, who, with admirable premonition, swiftly displays a fondness for Jonny Greenwood’s prominent cheekbones. He, inevitably, behaves like a gentleman. His brother, Colin, is similarly polite, and there’s no sense coming from any of the band that this represents the fulfilment of a long held rock & roll fantasy: there’s no hurried necking of beers, no backstage shenanigans, no foolish conduct of any sort. Life spent on the road with Radiohead is no Valhalla.

I talk to them eagerly about the brilliance of ‘Creep’, and they seem neither uninterested nor unusually responsive. Naturally, no one’s rude, so I stay there a while, albeit driven by my enthusiasm for their music and my solidarity with their cause rather than any sense of intimacy. But while no one would notice if I weren’t there, I never once feel as though they wished I were someone or somewhere else. I’m simply a face to whom there’s no need to be impolite, and they’re really only concerned with the job they’ve come here to do. Still, I have this feeling that I, alone with the few, have recognised untapped potential, that I’m – though the phrase has yet to be coined – an early adopter. I’m convinced that ‘Creep’ is an unmistakable anthem, and there’s no way it can be overlooked. I’m just one of the lucky ones who knows this because I’ve got one of the first copies. It’s obvious others will soon agree.

Fifteen sheets to the wind, however, isn’t a good place to be when you’re in the mood to show off. Soon after the band start playing their new single, I edge my way to the front of a sparse crowd and, as Jonny Greenwood crushes out those iconic chords, I throw my arms into a crucifix and bellow along with the lyrics, directly beneath Thom’s microphone stand. Worse still, I do so with my back to Thom, taking on the responsibility of cheerleading with an uninhibited passion. My hands rise and fall as I exhort others to sing along with me. They stumble back, embarrassed, leaving me isolated in front of the singer. I carry on regardless: I am Radiohead’s champion. I am a complete disaster, as well, but soon enough everyone else will look stupid for not having been down there with me.

Another few months pass, and I drive three plus hours from Exeter to North London on a rainy Sunday afternoon in March, 1993. Belly are headlining The Town And Country Club in Kentish Town, and The Cranberries – currently seducing the British music media on the back of their debut single, ‘Linger’ – are on first. Former Throwing Muse Tanya Donnelly’s stab at mainstream stardom are all the rage, and I know I should be excited to see both bands, but really it’s the middle act, Radiohead, that are the main reason for my trip. By now, ‘Creep’ is a hit stateside, and it’s infiltrating the UK too, having been recognised as a ‘Single Of The Year’ by a number of publications. Their debut album, Pablo Honey, meanwhile, has been on the shelves for two weeks, stirring up what I describe in The Third Degree as a buzz as big as Suede’s the previous year. "That was quite some buzz," I add, not as droll as I think I am.

I remember little of the show, sadly, aside from being excited at the chance to say hello to their tour manager and consequently ingratiate myself backstage. I find my way to their dressing room, but they’ve already got their fair share of hangers-on, so, having briefly said hello to the four of them I can find, I ask where I might find their frontman. There’s a nonplussed reaction, a collective shrug of the shoulders. Sandwiches wilt under mirrored lights. Stepping outside into a concrete corridor, I can hear laughter coming from Belly’s dressing room, out of which people are spilling into the passageway to my left. To my right, some dozen feet away, steps lead down towards the stage, and I hear a shuffling sound, or maybe a cough, emanating from a hunched, gnomish figure lurking at the top. It’s Thom, and he’s alone. I hesitate, then shamble over. We exchange pleasantries, but conversation stalls, and Thom begins to look increasingly gloomy. It’s time to get me coat.

Fast-forward another twelve months to 27 May, 1994. It’s almost two years since Thom and I shared that awkward coffee on the eve of Radiohead’s debut. That’s me again, clinging to the balcony railing of London’s Astoria Club. What’s happening in front, from the moment Radiohead tear into ‘You’, is an almighty revelation. Whatever I may have thought of them in the past, there’s an unprecedented urgency to their performance that nonetheless refuses to diminish the fluency of their playing, the ragged sketches they’d drawn on Pablo Honey delivered as sculpted, muscular beasts, elegantly wild yet mature. In a sign of their growing confidence, they drop the unfamiliar ‘Bones’ second song in, and ‘Black Star’ follows after a furious ‘Ripcord’, Yorke introducing it with a pre-emptive, self-deprecatory apology for performing another new track.

It’s far from the last, too: soon we get ‘The Bends’, ‘Fake Plastic Trees’ and ‘Just’, Yorke, in his Haiwaii ’81 T-shirt, bug-eyed and snarling, jerking his head convulsively to one side like Ewen Bremner in Mike Leigh’s Naked. To his left, Greenwood Jr, his own shirt several sizes too small for him, handles his guitar like he’s trying to tame it, while his brother lurks in the shadows, calmly bobbing his bobtailed head as he uncurls ingenious basslines. At the other end of the stage, Ed O’Brien – dressed like he’s auditioning for Mandy Patinkin’s role as Inigo Montoya in The Princess Bride – wrangles unforeseen chords from his instrument, slapping meat back onto the bones of their songs as though he’d previously underestimated his capabilities. Behind them, calm and unobtrusive, Phil Selway holds things together. I’m slack-jawed, wide-eyed and bowled over.

They return for an encore, playing ‘Street Spirit (Fade Out)’ for possibly the first time in public, revealing a sensitivity that ‘Creep’ only hinted at, its understated beauty seductive and spellbinding. Afterwards, I’m unusually speechless, and when the band appear in the Keith Moon Bar later on, while I’m sinking dirty pints at an adrenalin-fuelled pace, I’m far too over-excited to even consider saying hello. I’d realised during ‘My Iron Lung’, unveiled almost half an hour into the show, that I’d never talk to them again. The way that barrage of explosions from Jonny Greenwood’s guitar blew apart Yorke’s artless melody, tearing it violently from the cotton wool of the song’s coiling guitar lines and consciously dragging bassline, ripped a hole in the world around me. This faultless exhibition of sustained tension and release confirmed that Radiohead had become what I’d always hoped they’d be. Within little more than a year, the world would at last agree.

So what does The Bends mean, a quarter century on from its March, 1995 release? Personally, it represents the end of a rite of passage: in the three years since Yorke and I had shared a coffee, I’d graduated from university, worked briefly in a record store, and then moved to the English capital, where I worked as a publicist for a variety of American acts. I took my job seriously: however late I stayed out partying, I was always behind my desk by 10am in an office above a piss stinking alleyway a few metres off central London’s Oxford Street. I’d left behind my comfortable upbringing to live in a shabby Soho flat – built for two, if shared by four – which provided a base for adventures I’d never expected to enjoy: I’d got drunk with Guided By Voices, barred Liam Gallagher from The Afghan Whigs’ dressing room, and smoked Snoop Dogg’s weed at The Word. It wasn’t always easy being posh in the world of indie rock: I was gullible and oversensitive, unsure of my place in, and unfamiliar with the customs of, London’s thriving music industry. But I felt like I’d come of age, and when I first heard The Bends it seemed to me that both Radiohead and I had reached the end of a crucial portion of an ongoing, thrilling journey. We’d shared similar backgrounds, had pursued comparable trails, and had even crossed paths along the way. In my mind, their triumph was emblematic of what I too had achieved: the fulfilment of my long held dream of an alternative existence in the music business.

To empathise with this far-fetched sentiment, there’s something you need to understand: despite all the opportunities fee-paying schools might offer, they’re not designed to propel people along such a path. (They weren’t back then, anyway.) A 1980s, middle class upbringing hardly groomed one for success outside the traditional professional establishments, and though there were rebels – the smokers, the tokers, the drinkers, the thinkers – for most of them it was a stance, an opportunity to enjoy freedom before they settled down in the home counties with a well-spoken partner, a couple of precocious kids, a favourite seat on the London train, and an inflated nostalgia for their misspent youth. "Just like your dad, you’ll never change…"

Having left university, I knew that my parents wished the time I was spending writing uncommissioned reviews for Melody Maker and NME was instead being spent preparing applications for jobs in more respectable fields. They weren’t unsupportive, but this wasn’t what they’d had in mind when they’d put my name down at birth for a fiercely competed place at a prestigious educational establishment. Still, if private schools insisted on one thing back then, it was instilling in their pupils a sense of responsibility. My own headmaster called this one of "the right habits for life", as important as keeping your fingernails clean and your hands out of your pockets when talking to staff. Whatever route was undertaken, you learned, you were to apply yourself fully to the task in hand. It’s one of the few things I grasped during those ten bleak years away from home that has ever proved useful at all.

It’s not too far-fetched to suppose that, like me, Yorke and his colleagues were reasonably cautious before they decided that music was a valuable pursuit. When families spend tens of thousands of pounds educating their children, only a few of their offspring dare reject the expectations that have built up around them. Even Jonny Greenwood, one imagines, spent a few sleepless nights at Oxford Brookes University before he walked out three weeks into his music and psychology degree to sign the band’s deal with EMI’s Parlophone imprint. Not that such a background makes things harder than it is for those from state schools. Far from it, obviously: the familial financial cushion that most privately educated school-leavers have is unquestionably a significant reassurance for the ones willing to take a risk. But you can hear in Radiohead’s Drill EP a need to be taken seriously; to – as the song said – "prove" themselves. Its songs are lean and considered, balanced by a rough and ready sound that suggests they’re scrupulously self-aware, uncommonly determined, and attentive to where they want to sit in the grander scheme of things. You can bet that their teachers soon claimed a part in the band’s global success.

But what does The Bends mean beyond my own narrow existence? It emerged on the back of an era in which music’s tectonic plates had been shifting violently. Shoegaze had roared, then whimpered; the baggy movement had collapsed in a comatose haze of its making; Britpop had gorged itself upon its own noxious legend; and, when The Bends was finally released, even grunge’s poster boy, Kurt Cobain, had been dead for a year. Judging from Thom Yorke’s DJ sets at Exeter University, the band would have been familiar with all of these movements, shifting from the predominant domestic British sounds of their school days to explore noisier sounds coming in from the US, their common thread a sense of independence and a distaste for the status quo. This kaleidoscopic amalgam of potential inspiration informed everything Radiohead did in those early days, even if it was yet to be distilled to its essence.

The Drill EP is, inevitably, stamped with the indie production tropes of its time. Truth be told, it doesn’t sit entirely uncomfortably alongside the likes of Kingmaker and Cud. But, by the time The Bends hit stores, Jonny Greenwood would be seen on Sunset Strip billboards wearing a T-shirt he’d bought at a show by Cell, a New York band championed by Sonic Youth. One member still recalls with pleasure how Thom Yorke once told him – after a show headlined by Radiohead – that Radiohead should have opened for them. The quintet embraced influences that felt disorientating, smudging familiar genre boundaries and pursuing avenues that dismayed as many as they excited, albeit on a smaller scale than the band would later attempt. But it wasn’t just critics that were confused about where they fitted in. Despite their efforts, Radiohead barely knew where they stood either. Everyone was scrambling for a new Seattle, a new Britpop, and times were becoming so desperate that, within months of The Bends’ delivery, the media would be championing ‘Romo’. Wherever you tried to place them, Radiohead failed to conform. This wasn’t what was expected of them.

If The Bends came from anywhere, it was from a desire to comprehend this confusion of influences. After all, the members of Radiohead, one senses, didn’t become a band because they wanted to make a noise, but because they wanted to make music, and, crucially, knew how to make it. Some groups form because of a need for camaraderie, or rebellion, or escape, but none of these seem relevant to Radiohead. Working together was simply the smartest option available to them: collectively, they could carry one other to their goal. They became a band, just as they’ve since become what they now are, because they embraced the duty of being Radiohead.

Becoming Radiohead took time, too: there was much to digest, so much to learn, before they could understand just what this responsibility meant. The Bends is consequently the sound of five men fighting their way out of a tangled web of conflicting convictions and prejudices with an uncommon earnestness, reconciling their tastes and their ambitions, sifting through The Pixies and The Smiths and Dinosaur Jr and The Beatles and Talking Heads and Happy Mondays and Elvis Costello and Tim Buckley. It’s the sound of five men taking an exploratory dive into deep waters, finding themselves lost, and still somehow redrawing the map of where it is they should resurface. It wasn’t called The Bends for nothing.

Before that, though, there was ‘Creep’. Love it or loathe it, it represents a critical juncture for Radiohead in their development, just as it embodies for me the night before the morning I realised how undignified alcohol could make me behave. It’s common knowledge that the band has leaned towards a negative sentiment for years: even Greenwood’s first, extraordinary interjection of noise apparently stemmed from his attempt to mess up a song that he thought was far too fey. (One might say he had a point.) But, in drawing upon what was happening on both sides of the Atlantic, ‘Creep’ combined a grumbling Englishman’s indie sensitivity with the sometimes nihilist, always principled spirit of the US guitar underground. Predictably, with Cool Britannia approaching its zenith, it was left to America to be first to ‘get’ it: in the UK, the track only peaked upon its first release at number 78 in the charts. But, after it became a hit stateside, the band conceded to a British reissue that made it into the Top 10. They’d just adopted their albatross.

Listening to ‘Creep’ now, it’s understandable why they were unenthusiastic about its British re-release, and why they soon found it so unbearable that it failed to make it onto their set lists for most of the 2000s. The appeal of such lyrical transparency soon dwindles when you’re forced to stand in front of crowds repeatedly denouncing your significance. What once appeared honest is rendered almost ridiculous by virtue of its repetition – for both the singer and the audience. No wonder Yorke looked so genuinely nonplussed in 1997 as he sang the song at Glastonbury: "What the hell am I doing here? I don’t belong here…"

Feasibly, there may be yet another dimension to their uncomfortable relationship with the song. By virtue of their upbringings, these well-bred boys were most likely indoctrinated with the conviction that such declarations of self-pity were hardly becoming when uttered from beneath a stiff upper lip. To sit about whining and whinging is decidedly non-U; infra dignitatem, you might say – if you came from the kind of establishment they did (though God help anyone who tried). These may not have been conscious beliefs, but they probably coloured their growing distaste for a track that had been very good to them. Still, whether or not this is correct, the truth is that ‘Creep’ contains none of the complexity of the music they were soon writing and, even amid other songs they were already playing, it seemed a little… trite. To some, their subsequent decision to bench it may seem precious, or at least disrespectful to fans, but honestly: imagine yourself, night after night, in front of increasingly huge audiences, having to pretend, in a tremulous voice, that you’re still the same jerk you were on that lonely night you first wrote the song. You’d soon start feeling sorry for yourself too.

In the year between ‘Creep”s two deliveries, Radiohead released two other singles. ‘Anyone Can Play Guitar’ was the first, and it coincided with the release of their patchwork debut album, Pablo Honey, in February 1993. It ridiculed the idea of pop stardom with unusually acerbic bitterness, something that perhaps contributed to its commercial failure: "Anyone can play guitar/ And they won’t be a nothing anymore," Yorke growled, adding wickedly, "Grow my hair, grow my hair/ I am Jim Morrison…" ‘Anyone Can Play Guitar’ appeared to be a reaction to the spotlight that ‘Creep’ had attracted, and, a year later, ‘Pop Is Dead’ – which, tellingly, never made it onto an album – was even more alienating for the media, as well as the general public, and presumably the band’s record label too. "Oh no, pop is dead, long live pop/ It died an ugly death by back-catalogue," Yorke sang, echoing Morrissey’s line from ‘Paint A Vulgar Picture’ – "Reissue, repackage, repackage! Reevaluate the songs" – in an ill-advised video that found him carried in a glass coffin, heavily made up like a dead fop.

Furthermore, Yorke wasn’t finished. "We raised the dead but they won’t stand up," he went on, "And radio has salmonella/ And now you know you’re gonna die", before he concluded, ahead of a whirring squawl of guitars, that "pop is dead, long live pop/ One final line of coke to jack him off/ He left this message for us". If the song’s meaning wasn’t clear enough, though, Yorke would elaborate on it at the band’s London’s Astoria show in 1994 with the words "Dedicated to members of the press, as it always has been," altering the lyrics to "one final cap of speed to jack him off", then muttering, "fucking bunch of losers". ‘Pop Is Dead’ appeared so contemptuous that it was hard, even for Radiohead’s biggest fans, to like.

Fortunately, Pablo Honey itself contained enough notable moments to maintain belief in their explorations. Admittedly, almost half of its songs were already available – the whole of the Drill EP was included, for one thing – but, if one accepted that the best songs were indeed the ones that were most fresh, it indicated that the band were developing at a pace. Sure, they still struggled to stand far above many of the other acts that were scoring 7/10 reviews in the music press: ‘Vegetable’ was merely lovable if one really wanted to love it, for instance, and ‘How Do You?’ could only just summon up enough bile to satisfy a sweaty teenage audience too young for The Sex Pistols. But in its two closing tracks it provided a signpost towards where they were moving. ‘Lurgee”s quiet compassion and ‘Blow Out”s lysergic drama displayed a mature aplomb that would prosper on The Bends, their willingness to let the music define them an overdue replacement for the record company styling to which they seemed to have fallen victim: the red and white striped trousers, the dubious haircuts, the ‘received wisdom’ that seemed to inform many of their visual decisions. "You do it to yourself, you do, and that’s what really hurts…"

These intriguing fumblings, with moments of generous inspiration scattered amid them, were a tentative reconnaissance, a preliminary warm-up, a necessary step in Radiohead’s evolution. In fact, Pablo Honey was an application letter, one might say. The Bends, of course, would be the interview. First, though, in October 1994, there was a stopgap EP, My Iron Lung, its opener in fact lifted directly from the tapes of the band’s monumental Astoria show, with only Yorke’s vocals newly tracked. "This is our new song," he wailed, "Just like the last one/ A total waste of time/ My iron lung", and every time I heard this I’d remember that disconsolate Yorke at the top of the steps at the Town and Country Club in ’93. They still loved making music, while playing live could be satisfying, and they probably enjoyed each other’s company too, but already Radiohead were learning that they didn’t like being in a band: all the rigmarole that came with it seemed only to inspire revulsion. Maybe this was less true for the rest of them, but Yorke, in particular, seemed to be struggling to come to terms with the games that they’d been led to believe needed to be played.

The Bends was made as Radiohead first began on this treadmill, and already they wanted off. It was, one suspects, a record upon which they knew they’d stand or fall, informed by everything that preceded it. In many ways, it feels more like a debut album than Pablo Honey – with its mixed bag of strengths – ever did, as though it were the culmination of a lifetime’s work. Second albums are notoriously difficult to make, and by all accounts The Bends suffered a more than troubled gestation, yet it still comes out sounding fully formed, defining them in a way that Pablo Honey by and large failed to do. The privileges and the prejudices, the accolades and the rebukes, their pasts and their presents: all of these and more converged as one, crashing and grinding into each other until they found their place, only to soar off on a new, graceful trajectory. It was the end of a rite of passage.

The songs themselves only need to be recollected here because The Bends became so omnipresent and inescapable, so much a part of the sound of summer and winter 1995, that its overfamiliarity bred a certain degree of fatigue. At the time of its release, however – in the wake of Definitely Maybe and Parklife the previous year – it appeared unusually literate and accomplished, and, in some people’s minds, it towered above everything championed by an over excitable press for years. If they’d been little more the sum of their influences on Pablo Honey, now Radiohead were like no one else at all – like no one apart from Radiohead, that is. Even this was a concept that would soon be demolished: each new record from the band would swerve passionately away from where they’d last paused. They’d reinvent themselves repeatedly, first reshaping alternative rock, then dragging intelligent techno and electronica into the mainstream, before exploiting their well earned, hard won independence by at least attempting to disrupt conditions precipitated by the arrival of the internet.

That was to come, though: in March 1995, they staked their first real claim to greatness with a 49 minute collection of accessibly timeless, visionary songs that may have gathered a little dust since, but which stand up remarkably well. Admittedly, The Bends was only quietly revolutionary: there were no heroics, no ill-suited bursts of attention-grabbing histrionics, merely layer upon layer of intriguing arrangements that demanded repeated plays to unravel. But that mysterious sound of empty space being filled by shimmering guitars at the start of opening track ‘Planet Telex’ now seems prescient: Radiohead were taking up camp in territory few people seemed interested in investigating.

This worked because The Bends‘ lyrics were more elliptical, and the songs more intelligent, than anything they’d ever tried. Indeed, they were smarter that almost anyone in mainstream ‘alternative’ music was trying to be, a far cry from the wilful idiocy and tabloid realms in whose direction every other band seemed to be drunkenly heading. The sonics of the album, too, were polished, yet rarely drew attention to themselves. Yorke’s voice, meanwhile, still seemed to slur from note to note in his quieter moments – though he continued to rage bitterly at other times – but he seemed to be inhabiting the songs rather than testing out a role, whether amid the crunching guitars of the title track or the tender acoustic strums of the heartbreakingly puzzling ‘Fake Plastic Trees’. On ‘Just’, the band might have given in to their American influences, but they still packed the song with colourful fireworks, and ‘Bullet Proof… I Wish I Was’ boasted a haunting, peculiarly English desolation. Then there was the lilting grace of ‘Nice Dream”s strings and Yorke’s impressively feminine falsetto, which gave way to an impressively dramatic flurry of squealing guitars, while, in ‘High And Dry’ and ‘Street Spirit (Fade Out)’, they mapped out a terrain towards which a pack of other songwriters would soon rush: anthemic, gutsy, midpaced songs of unapologetic, but never over-egged, sentiment. Few would ever do it so well.

Radiohead, of course, would soon leave these copycats trailing, and many of us would travel with them, leaving The Bends behind. In fact, in a sense – especially in the light of what came after – The Bends nowadays sounds a little gauche, as if it’s tied to a period of Radioheads’ lives, and indeed our own, whose ideals have long since withered. Since then, we have grown wiser with experience, and the cultivated excesses of OK Computer, and the stubborn experimentalism of Kid A and Amnesiac, have underlined the band’s insistence that great musicians have a responsibility never to stand still, a reminder of an older generation who challenged themselves to constantly refine their talent and explore new domains with each and every release. The Bends, therefore, is attached to the ‘old’ Radiohead, a band who, for a while, were compromised by major label practises but who, in overcoming their distaste and disenchantment with the institutions into whose beds they’d unwittingly climbed, surpassed the promise others saw in them. It may exude an awkward, sometimes unwelcome nostalgia, but remember that it once offered far, far more than that. Without The Bends, one imagines, Radiohead might never have become what they are.

So you see that man up on stage, his arms twitching spasmodically, his voice like an angel’s, his colleagues filling up arenas with ever-restless inventiveness? That’s Thom E. Yorke, lead singer of Radiohead, one of the greatest groups to have emerged in our tiny little lifetimes, and it all started with The Bends. Now, you see that fellow buried deep in the crowd, his balding pate lit up beneath the moon, still struggling with ghosts from his entitled youth but determined to leave them behind? Yeah, you guessed it: that’s me, once again. Did I tell you I knew them when I was younger? They couldn’t give a damn, of course, but I’ll be proud ’til the day I die.