An Evolutionary Music is a beautiful, beguiling volume of timeless pieces that resound from a solitary path emerging just beyond the crossroads of free jazz, psychedelic rock, West Coast minimalism and European electro-acoustic composition. Indeed, many of its tracks are hypnotic enough to induce states outside time with their combination of looping saxophones, spiralling electronic rhythms and mesmeric synth lines. For many (myself included), this release, which covers original recordings made between 1972 and 1979, will be a first encounter with Ariel Kalma’s rich blends and bold experimentations – perhaps a symptom of his defiantly individualistic attitude that so informs his unique sound. As he reveals in the informative booklet accompanying the release:

"as was my motto at the time, ‘Why earn a living when we already live?’ I would not compromise to the expectations of music busy-ness. As I resisted learning to read and write music, I remained autonomous in order to express my own sound as it came from inside. I love the freedom to go anywhere. With no expectations, we have no disappointments."

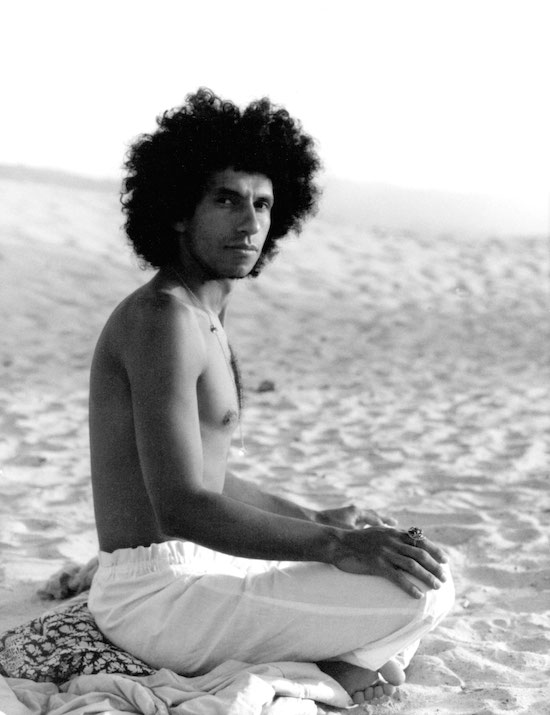

Having initially spent time as a gigging saxophonist in the French jazz and rock scenes of the late 1960s, while studying computer science at university in Paris, Kalma went on to become an engineer at GRM, the pioneering, state-funded heart of experimental electronic and tape music formed by Pierre Schaeffer. These wide-ranging experiences in improvisation and avant garde techniques were extended further through Kalma’s travels outside Europe, especially in India and the US, where he further developed a highly idiosyncratic approach to composition and performance. While echoing aspects of the mindblowing musical revolutions happening across the globe at the time, his emergent sound also anticipated future styles and methods, including trance techno and bedroom-studio electronica.

Kalma is now based in Australia, where he runs a music label of multicultural styles while continuing to develop his praxis both as a personal experimental quest and a therapeutic resource. It seemed about time we talked to the composer to find out how he carved his own path, unconcerned by obscurity and instead focused on the rich rewards of sound itself.

Your new archival release, An Evolutionary Music, provides a wealth of unreleased recordings made between 1972 and 1979. How did this project come about?

Ariel Kalma: Matthew [Werth, of Brooklyn-based label RVNG Intl.] connected with me about making an inter-generational recording for his series [FRKWYS, which hooks up comparatively new musicians with more established, pioneering artists] and I gladly accepted because I love to work with younger composers as an exchange of energy between generations. So they came here with Robert Lowe [aka Lichens] and we spent a week recording [an yet-to-be-released album and documentary film]. During that time I explained to Matt that I was doing archives of my early work, so we listened to some of the material and he said he was interested to do a double LP and we went from there. We chose the tracks which we both felt comfortable with and I think Matt did a great job to present my work – I’m very happy about that.

During the period An Evolutionary Music focuses on, you didn’t seem to release that many albums – just two, I believe: Le Temps Des Moissons (1975) and Osmose (1978). You suggest on your website that you didn’t always "remember to press record" – were you more interested with playing in the moment?

AK: [Laughs] Well it was not only that I did not remember to press record – the story with [that] is sometimes I would go on a meditation journey – you see, for me, music is the closest thing to silence, so when you are in a city like Paris, where I was at the time, which is busy and noisy, music created an environment where my mind could let go and I would go on this journey into self-discovery – exploring whatever is the inner realm. I play generally with closed eyes and many times it kind of starts weirdly: I close my eyes, I start playing, generally with a drone, like in Indian middle-age music [from the 12th century onwards]. It sets up a tone on which you can develop harmonics, as opposed to harmonies with changing chords in the western world. That’s what I’m interested in creating, harmonics of music, so sometimes I would start playing and not always remember to press record.

But I remember many times to press record actually – that’s why I have archives [laughs] and many times it was not really meditation, it was just playing music, to compose something. I have lots of archives, more than what is on this double album

This time period also seems to represent three key, formative stages in your evolution as a composer and musician. Firstly, please tell us a bit about your experiences in Paris in the early 1970s, where you were based and studying computer science at university while playing saxophone in jazz and rock bands. Did this provide you with a firm foundation for your experiments in sound?

AK: Well, yes and no – it’s an interesting question. I was studying computer science at the Paris University, which was more ‘mind-y’ and so, I love to play saxophone – I [also] played the recorder sometimes, but [in] rock and jazz bands there was not much room for a recorder [laughs], so I played mainly saxophone and I started feeling a certain limitation with the music. That’s when I bought my first Revox, a tube tape recorder. I was selling them in a shop during the weekends to earn some money for my studying so I knew this tape recorder inside and out, and I started to experiment with the sounds. But this has nothing to do with rock & roll, it was more experimental music where you would re-inject one channel into the other and when you pressed record, if you really played with the volumes and the levels, you could generate some kinds of echoes and reverb.

Then you travelled in India in 1974 and 1975. How did this trip influence you and your music? (As perhaps evidenced on your debut album, Le Temps Des Moissons, recorded at home in Paris upon your return.)

AK: When I went to India, it was not only a culture shock but a discovery of what real tuning means and a totally different way of playing music. The most important things I learned in India was to tune the tambura, which is based on creating a flow of harmonic frequencies which incorporate all the important notes in the scale in which you have tuned, kind of a natural evolution to the drone music. Basically, I learned so much that when I came back this album, Le Temps Des Moissons, was all about tuning not only the saxophone with the droning effect in the background, but to tune also the loop. It was not a closed, digital loop where it repeats constantly what you have done once; the open-loop system I designed with two Revoxs – what you play you get it back [but] changing constantly [the] tuning not only [of] the tone of the saxophone, but also the precise timing, like tuning with the rhythm; and that was like a meditation in itself and made Le Temps Des Moissons a special album because it was all about this tuning for those two long pieces [the title track and ‘Reternelle’].

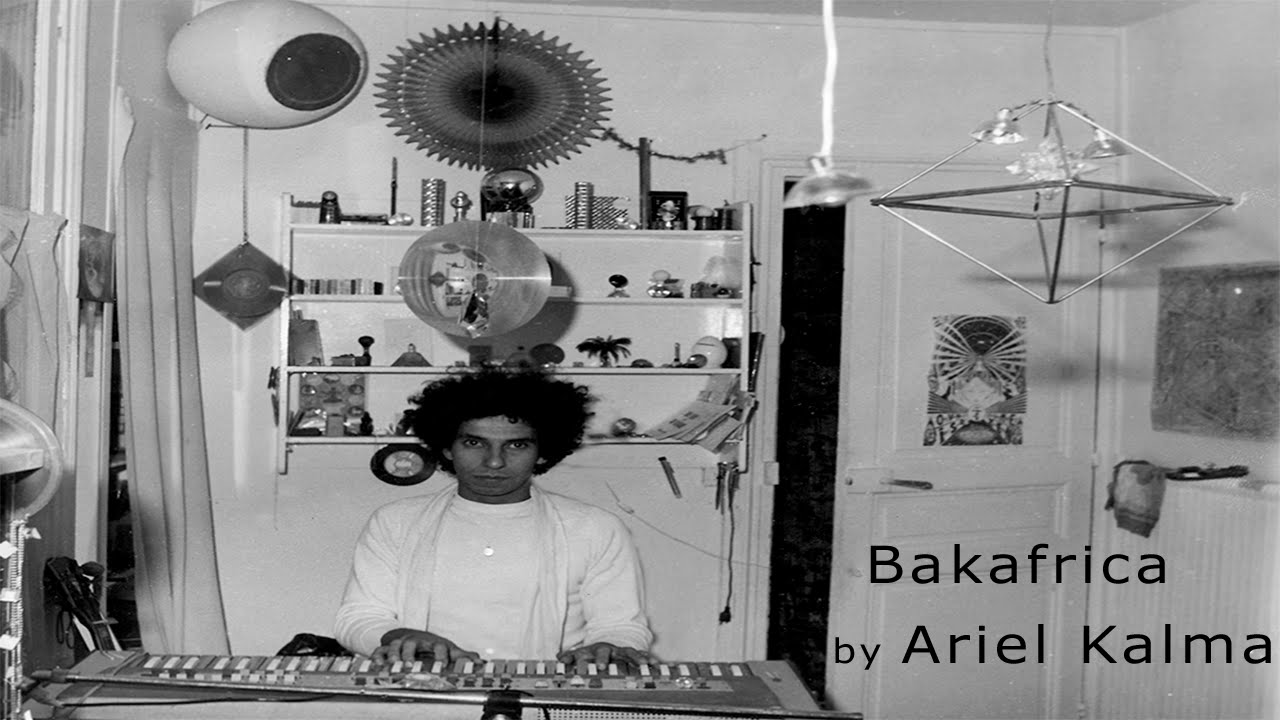

The middle piece, ‘Bakafrica’, was a different approach because it gathered several musicians from different regions, including my friends Brahim el Belkani and Loy Ehrlich. When we started, I said, "Okay, let’s do a piece which has no fixed tempo," because I wanted to do an opposition from the fixed tempo of the open loop with the two tape recorders. I said, "The tempo will always change, but openly so that we play together and we see what’s going to happen." And I said the second requirement was that "we’re going to play the music as if we’re on a camel’s back on the desert, so what would it feel?"

You then visited New York in 1976 – how did this further modify your approach to sound?

AK: [I was] invited to join a theatre group there, but this did not work out so I was left alone in New York. And that was the beginning of another adventure. I was sleeping in a church but I was sleeping during the day [laughs] because I was not supposed to be there, so I would sleep during the day and go out at night, which was very interesting because I saw the night part of New York. I played the harmonium in the church and trained with my soprano saxophone to do circular breathing in the sub-basement foundation part of the cathedral there, which had a big sound.

Your second album, Osmose, released in 1978, blends your music with field recordings made by Richard Tinti in Borneo. What inspired you to incorporate the sounds of nature into these compositions?

AK: When I was working at the GRM as an assistant engineer I discovered a tape with simple birdsong – one bird – and when I listened to it I heard such a melody and rhythm I was fascinated to practise with it, so I incorporated it in a recording. People knew about that at the GRM and when Richard Tinti came back to Paris from Borneo with 15 hours of field recording of the jungle and asked what he could do with it, they directed him to me, saying, "This guy plays with the birds! Go see if he’s interested…" [laughs]. At that time I was preparing my second album with music and it was pretty well advanced, I had most pieces, some had a harmonium in the church which I recorded myself also. Then this Richard Tinto came to me and asked me to listen to these tapes, and I listened and I started hallucinating – I could hear these sounds from the jungle, I could hear their melodies in the same pitch of what I was preparing as music! So I put them together, and I realised by choosing different moments of the jungle and different moods of my music that they just would match – that’s what I’m talking about [by] hallucination. Actually I was trancing so much when I mixed Osmose that I literally fell on my mixing table several times, it’s hilarious. It has happened along the years [laughs] that I trance out, I still sometimes trance out when I fall on my keyboards and computer sometimes.

Throughout An Evolutionary Music and your releases of the time, your compositions combine the craft of playing sax and flute, harmonium and organ, with technological experiments involving tape. What first turned you on to the role technology could play in your work?

AK: I went to a trade school where I learned electronics. I was not so interested in learning how to repair or how to measure, but I was interested in how to make sounds [out] of anything. So, I made mobiles with circuits, musical mobiles and sculptures, and I learned how to manipulate sounds. I was always into incorporating the technology of what was surrounding me because I think great music is made with what surrounds us.

Later, when I was doing computer science, some parts were also boring to me and I started becoming interested in the sound which you could make from the ribbons feeding the programs in the huge IBM 360 computer I was working on. I observed if you had a sequence of holes in either the perforated cards or the ribbons then you would have different sounds. It was not interesting per se, but I started to play with that. Yes, technology has always been a part of my work.

As well as being an early adopter of modern technology, there is a strong spiritual dimension to your music. Where has this come from and has it changed or remained a constant throughout your career?

AK: Absolutely, absolutely. I think it traces back to, well, I had an early experience when I was really a kid, a boy scout, and we were playing all kinds of games. I must have been 13 or 14, [and] at one point we played those games where you hold a choke around the plexus, basically preventing to breathe, and then you basically faint. Anyway I did it and I fainted and during that time I went into a spinning wheel of amazing details and when I came back, the wheel was spinning slower and slower, and I realised something – I had been touched with seeing another part of life or another side, and that was really deeply spiritual for me. So after that I always was interested in that dimension, so to speak.

Dimensions of spirituality [are] very important in my life as a composer because what we discover in meditation or deep relaxation is such an inspiration that we can compose new pieces from there, and I’m sure many of my fellow musicians would agree with that.

In French, ‘spirit’ has a different connotation than in English – it can be the connotation of being a spirited person, but it can also mean what is not daily life. So, yes, all these devices and mantras and meditations and trainings are made for us to go in a place where we can be completely in the present, which means having a global view.

Although not released at the time, many of your compositions that followed the period covered by An Evolutionary Music were made to induce trance-like states, to help people meditate and/or transform and heal themselves. How did you get involved in music therapy?

AK: This is what accompanied me for a long time through all kinds of workshops, groups, and trainings which I did as an assistant or group leader or musician, to provide an environment of sound in which the mind can relax and we can reach a deeper state of understanding. Because we need gimmicks – if not then the mind takes over and starts going around and getting us crazy. To quiet the mind we need help and music is a great, great help for this. That’s how I got involved in music therapy, in these groups where we had maybe sometimes 50 people either frantically moving to raise the energy or laying down and breathing deeply while I was doing all kinds of sounds with Tibetan bowls, bells, didgeridoo, saxophone, and drones. After that we would talk and treat, sometimes with wonderful group leaders, what’s not right or not in tune in the person [to] provoke a deep healing.

Is this an aspect of your music you continue to pursue?

AK: Well, I am at another place now because there are so many people doing this quiet music and I’m still doing quiet music, but now I discover that something else is missing in our life – the digital life, the modern life, where everything is pre-arranged, pre-organised. What I feel is that we are missing the wild, the ‘fire in the belly’, as some group leaders would say.

Modern life has erased part of our being, so how do we regain that part? Well, this is where I think we could get back to a more wild music – you know like rock & roll was the need for a certain freedom to be born, modern art is a freedom, a liberation from tradition, ‘doof’ [the Australian outdoor raves most commonly playing trance] is the mechanical – I can’t say freedom because it’s not a freedom – it’s the contrary, so it’s part of the problem not part of the solution. My desire is to be part of the solution with what I call ‘tribal music’ – tribal music has the element of wild. Of course, I would never forget harmony and things, but that’s why I’m happy to do a label [Music Mosaic] where we started with soft and melodic music but I [have now] started to feel the need for the wild man and woman to emerge out of the polite society which stays in the norm, and if we look around people have the desire for that.

You now live and work in eastern Australia, where you have set up a culturally diverse record label, Music Mosaic. How has this influenced the music you make today?

AK: In each one of my Music Mosaic compilations I introduce something which is different from the [rest of the] compilation. For instance, in a compilation called Fire Drums it starts from cracking the match to lighting the fire until the last embers of the fire – I chose a track as the last embers of the fire which really was only slightly glowing by an unknown band [Tervakello] with very, very sparse percussion.

I tried to introduce things so that it brings an element of difference, so what I want to say with that is: look, ‘doof’ is called four-on-the-floor [taps a plain 4-beat] so there is no variety in rhythm. If you take middle eastern rhythms they have 9/4 time signatures, 11/4, and it makes those amazing different tempi, it makes those unbelievable pieces of music where we don’t know where it starts or where it ends. We are not accustomed to that. In our modern world it’s more mechanical, and mechanical is the danger for me. If we become robots then we have lost our human nature – what I want to introduce with Music Mosaic is the human nature again, to bring back some elements of the wilderness and polyrhythm, because that’s what it’s about – the polyrhythm!

An Evolutionary Music is out now on RVNG Intl.