Yes, yes – a call to meet Bryan Ferry. What would you do? I say yes.

So first of all, at the end of a weird summer, I float off to Kensington, down Avonmore Road, get buzzed into Bryan Ferry’s studio… and I go down, down, past the wall hangings, past the wardrobe rooms stuffed full of Louis Vuitton jackets and Italian shoes, past the Roxy Music album cover outtakes, past the library where books of early 20th century art sit next to a history of the blues and The MGM Story, past what I think must be Andy Mackay’s original VCS3 synth, the one which Eno’s shiny fingers are twiddling in all those clips of ‘Virginia Plain’… down, down, into the control room where there’s a cup of tea and a finished mix of Bryan Ferry’s new LP.

Even at my age – no, especially at my age – my first demand of pop, or maybe my last, is ‘just surprise me’. And there are few surprises here. Even at his age – especially at his age – Bryan Ferry has freedom of movement, and yet he holds himself so still. Avonmore, the new LP, sounds much as you’d expect a new Bryan Ferry record to sound. Frictionless and distantly funky. Heavy with half-felt regret. Plush and vague. An expensive gas. There’s only one surprise: it’s fantastic.

Avonmore feels like a natural development from 2010’s Olympia, which was strong and slinky without ever feeling quite like a classic; suddenly Ferry has come back into focus. Age has oaked and peppered his voice – not so glassy, not so arch. Emotional, despite himself. You’d think that might spoil things, but really it doesn’t: these songs of hazy love and discontented opulence are just as poised and inscrutable as you’d hope. On ‘Soldier Of Fortune’, a co-write with Johnny Marr, a parched Ferry vocal is sealed inside the moving waters of Marr’s guitars; ‘Driving Me Wild’ and ‘Lost’ are daydreams of night-time, sat on the bright side of rainy windows. Best of all is the title track, which I ask to hear twice: a glowering locomotive, a thriller. Even on the so-so songs, you can simply float across or along or in between the thousand million billion layers of Nile Rodgers, Marcus Miller, ennui, rapture, despair, some things too far-off and indistinct to properly identify (there are things twinkling in the distance). No surprises, except that this is unquestionably the finest music Bryan Ferry’s made for 30 years.

No surprises? Bryan Ferry doesn’t have to move with the times. All he has to do is this. All he has to do is… float.

A few months later and we’re far away; as far away as Copenhagen, with all of its money and its green ramparts. The air is clean and mild.

The hotel in which Bryan Ferry is sort-of waiting for me is the kind of place where top-hatted, swallow-tailed doormen smile at you knowingly as you pass, in your frayed best jacket and second-hand shoes, and a face which – try as you might – betrays a hard life, lived hard; they can tell you’re only passing through, but hey, so are they (we’re all here to serve, in one way or another). Once you’re inside, you’re moving through shades of cream, avocado and coral, gold plated clocks and chandeliers, and luxury’s sad spell is cast. You feel transformed. You feel like you should be grateful, or something. You need a special key to get the lift to Bryan Ferry’s floor.

His suite is understated: a desk, a sofa, an armchair. A set of double doors, closed on the bedroom. The last time I sat down in a suite like this was 20 years ago, interviewing Barry White in London. He left me on my own at a huge wooden table in an anteroom – to build some tension, I think – then finally made his entrance in a red silk dressing gown with gold trim, red pyjamas with a gold monogram, a red jewel in a gold ring. He pulled out his cigarettes and put them on the table: Marlboro reds, with a gold Zippo. He was a star. Making himself distant was a way of getting close to you.

But Bryan Ferry is there immediately, smiling and extending a hand – he’s met too many people but he’s not going to hold that against you, yet. Bryan Ferry is a star as well, but a very different kind of star, keeping a very different kind of distance.

Let me tell you something now: among music writers, Bryan Ferry is known a difficult interviewee. Not because he’s thick, or truculent, or spitefully arrogant – quite the reverse. He’s calm, quiet, slightly shy, extremely guarded, too smart to say silly things (at least since the flap about that Nazi nonsense, back in 2007). Very rude people have called him boring. Certainly he has… well, a gentlemanly reserve, but also an obstinate vagueness. Several of my journalist friends have interviewed him before; I asked around. One described the experience as "like talking to Sergeant Wilson".

But how? How can a man so fundamentally fascinating – and whose whole career has been, in one particular sense, about making his personality glow – be so… so I-don’t-know? It wasn’t always like this. In early interviews he’s playful and cocky, as playful and cocky as the music he was making. I suppose that interviewing Bryan Ferry is still like listening to the music he’s making: you’re not so much connecting with a human being as sliding around on a smooth and seemingly edgeless surface. Some find that maddening. For others, it creates a sense of intrigue. Me? Well, I’m not here to judge. He’s floating through his world, and now he’s going to float through mine. I’m just here to listen.

Bryan Ferry takes off his jacket; he casts it aside and floats, downwards, into the armchair. I perch on the edge of the sofa like someone going somewhere. Arranged on the table in front of us: a silver cake stand loaded with blueberries and raspberries; a small bowl of nuts; several kinds of teabag with a china pot of boiling water; a bottle of champagne on ice, just in case.

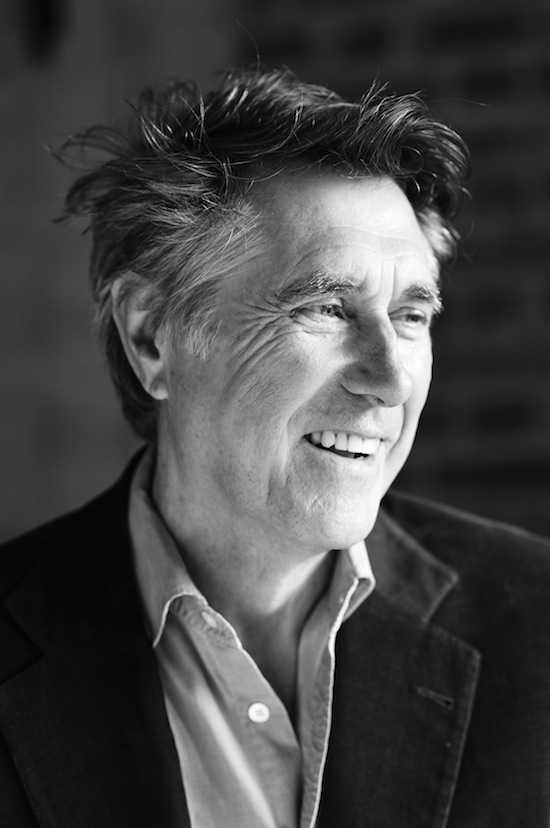

Blue cords, blue v-neck, a collar and a tie. Smooth brown brogues. Hair that’s greying but still very much there. It’s hardly fair. Here’s an urban legend that’s true: about 20 years ago Ferry, then about 50, was being photographed by Snowdon for the men’s edition of Italian Vogue. Someone walked into the studio to deliver a parcel, glanced across at the session and said to the stylist, "Who’s that then? He looks like a young Bryan Ferry."

But today, Bryan Ferry is tired. From what I can gather, he’s only just arrived at the hotel, and before that he’d only just got off the plane. Before we’ve even begun he’s rubbing his eyes, examining the lush depths of the carpet through the gaps between his fingers. He pours some boiling water onto what looks like a pillowcase folded over the side of a china teacup. "Do you want some of this?" he asks, quietly. "It’s just… lemon." In the distance, a bell in one of Copenhagen’s countless baubled spires is striking the quarter-hour. What would you do? I ask Bryan Ferry about his new LP.

"Well, we made it in my studio," he says (no surprises, again). "I wanted to make a good album, and I wanted it to be material that I could perform live. You become acutely aware, if you’re touring a lot, that you need new songs to invigorate the live show. And make it interesting for yourself, too."

I’m straining so hard to hear Bryan’s filo pastry whisper that when the room warms slightly and a bit of ice gives way, the sudden lurch of the champagne bottle sounds like a thunderclap. I jump, visibly. I don’t think he really noticed.

Do you still write on the piano?

Bryan Ferry: Always on the piano.

Well, your earlier songs were very obviously written like that, but it’s hard to imagine a lot of your recent songs being written at all. They’re feel records; they sound like they were built, not written.

BF: Oh, yeah. Absolutely, a lot of the solo records started off as grooves first, which I then wrote to. But I think this album is a bit more song-based, and I think it’s benefitted from that. At home I don’t really have any drum machines or anything like that, I just have a piano and a cassette machine, an old-fashioned one, an old relic which I’ve always used. When something good happens I record it, the bare sketch of it, and then I take that to the studio and start on it there. I very rarely play the piano at home. Deliberately, so that when I do play it, I love it. I mean I don’t practise, which is pretty apparent I think. I’m not a good musician. When I’ve made solo albums I’ve tended to get people in who are much better than me, but it’s sometimes ended up with the record not sounding enough like me, so this time we dispensed with virtuoso keyboard players and I did most of it myself.

It sounds – from what you say and from the records – as though creating your music is a co-operative thing. But you don’t have a regular band, do you? How do arrangements this dense develop?

BF: I do it one-to-one. Very rarely do I have more than one person in at any one time, apart from the engineer and the producer. I guess it’s a control thing, maybe. I find it more creative for me. I get more creative input that way.

It’s more painterly, right? You can stand back from the easel with a thumb up sideways, squint at the work, decide what it needs…

BF: Oh yes, it is like that. It’s very like that, because when the players have gone, then we have the gruelling job of editing what they’ve played, which takes hours and weeks. That’s the bit I enjoy the most, I guess. It’s more like sculpting, sculpting something from what they’ve played. Although I work with people, some of the people on this record, that I’ve worked with for years. You can say. "It’s not his band," but in a way they are, because I mean Nile Rodgers and Marcus Miller are two guys I first worked with, separately, in 1983, and they’ve both played on several albums of mine since, so we go back a long way. It’s sort of a group that isn’t a group.

CRACK goes the ice. The bottle shifts again. This time I’m ready. But the room is warm. I feel like I’m falling asleep. Or floating.

I can still remember the first time I heard For Your Pleasure, a Belgian pressing bought from a secondhand record shop in Brussels on a school trip to the Espace Léopold. This, I decided then and there, was going to be my future: weird sex, alienated wit, European cities, unnatural noise. It kind of came true. It kind of didn’t.

But Roxy Music were more than just kids’ stuff. They had a rather more sophisticated, more constructive relationship with fantasy. Roxy were arguably the first band to fully understand postmodernism, and one of the last to be empowered instead of cowed by it. An art band who were not just fundamentally and enthusiastically pop, and who chose not just to play but to perform, they were able to wipe reality clean, projecting a newer and more engaging reality of their own which would, as it instantly faded, call into question what "reality" means. (Listen to how Ferry sings the word "real" in ‘Mother Of Pearl’, the most relentless of his early songs.)

This original Roxy Music – sleek, with a thin edge of hysteria – were chimerical, insanely stylised, always gently fatigued. This original Roxy Music – a faintly disturbing mirage of luxury – were beautifully recherche, darkly irresponsible. And that original Bryan Ferry was a kind of perverted alien Fonz, more vampiric than aristocratic, closely set eyes and coconut tears, a modern grotesque, a peculiarly unsettling creation as well as an electrifying vocal stylist and a writer of simple songs which went a great deal further than simple songs would usually dare to go. Their experiments in the blending and juxtaposition of organic and inorganic sound have never since been repeated, let alone extended.

(And Roxy never lost it! Even once their music slowed and chilled, they were never just tasteful – records like Flesh + Blood don’t blaze with inspiration in that same uncanny way, but if you scrub your brain of the gloop they inspired, it’s quite extraordinary how they assemble a scattering of silvery lines and dots into a sighing, luminous whole.)

People talk about Roxy Music as an art-school band – which of course they were, their application of art theory to pop being uncommonly explicit even for the time – but Bryan Ferry was never an art-school kid in the way that John Lennon or Keith Richards or Ray Davies were. The postwar British art-school system was crucial to 60s and 70s rock because of its energising and radicalising effect on working class and lower middle class youth: the old art colleges were mostly polytechnics, places to send the bright kids who’d turned into teenage tearaways, in the vain hope they might fulfil their potential in a looser, more laid-back environment, maybe make a career for themselves in commercial art or graphic design. What actually happened was that the sharpest of those kids, put in contact with fiery new ideas about action and feeling and self-expression, applied them all to rock & roll and helped revolutionise British culture. We all know that story, right? But Bryan Ferry, despite his rootsy roots, was never one of those kids. His art education was the logical continuation of his first love, not a last chance saloon.

You didn’t attend one of those art colleges – you studied fine art at a red-brick university. Presumably this wasn’t quite the same thing?

BF: Yeah, it was slightly more formalised, I guess. I wanted to go there in particular, to Newcastle University, because Richard Hamilton was teaching there and my art teacher at school had been, and he recommended that I go there. It was a separate art department, but what was nice was that it was within the university, so you had contact with all these other supposedly bright kids who were studying maths, chemistry, medicine, or in my case architects – I knew a lot of architecture students.

Was it a good place for a rock & roller?

BF: Yes, due to Richard Hamilton teaching there, to a good extent. For me he was a kind of link to America and Americana. Half the kids, those of us who were into Richard and Richard’s style of art, we were into American stuff, American art and music – although the cool crowd were into Motown and surfing music, and the Everly Brothers and stuff like that, while I was leaning more towards Stax, a little less pop. And then there were another group who were more beards-and-sandals, you know, a bit more French or something. Dadaists and that kind of thing. But you were studying art because you were creative, and so you wanted to be, well, arty. So music was an obvious thing to get into.

Are the British scared of art, do you think?

BF: Well, not in London, now, it’s become the art capital of the world. But then I guess London isn’t the same as England. I don’t know. Is it?

This conversation isn’t going anywhere. Bryan doesn’t seem to want to say anything. We’re just sort of… floating. I’m trying to get through, but what can you do? The room’s still getting warmer. Bryan leans forward and pulls his v-neck over his head – for half a second it catches on an ear or something, and lodges there. I’m staring at a 69-year-old Bryan Ferry with a v-neck jumper stuck over his head. Is this what it’s come to? Thankfully, no: one more tug and he’s free. He casts the sweater aside. His hair still looks fantastic.

Allied Carpets advert, not actually by Bryan Ferry, apparently

I’m trying to get through. What would you do?

Bryan, it’s a curious thing. Since Avalon I suppose, you’ve been making this music with no kind of edge on it at all, in which absolutely nothing happens, musically, to startle or disorientate. This is almost a definition of blandness.

He chuckles evilly. I didn’t expect that.

BF: It’s something I’m always very worried about, blandness creeping in. I have sensors, you know – "Is that too safe sounding?" This isn’t a particularly experimental album. It could have been a great deal more experimental, if I’d had Brian Eno playing on it or someone like that – although there isn’t "someone like that" because he’s unique – but that could have taken it in a different direction which would have been just as interesting.

The thing is, though, when it works, this music isn’t bland in the slightest. It’s full of a very particular kind of life, a very subtle energy. Where do you find that?

BF: Well, my team – and it is a team effort – some of them are quite young, you know.

You’ve spoken before about being naturally quite conservative. And yet you began by doing such radical work.

BF: Yeah but you look through the history of art and you’ll see that people who did even revolutionary work were often quite bourgeois in their life and their tastes. They needed that anchor to get the work done. People like Manet, Degas, smartly dressed guys who might look like bankers. It doesn’t seem odd to me.

In many ways, your story – the Bryan Ferry story – is all about a steady progression from a dark and witty parody of elitist sophistication towards the real thing.

BF: Well, yeah. I guess I was interested in… lifestyle choices, or something.

(I try to imagine a less precise response than that, but I can’t.)

BF: I don’t know how much I was influenced by movies, but probably a fair bit, seeing people like Fred Astaire, Cary Grant in North By Northwest, and thinking, Cor, I really like that. Also, as you get older you meet different kinds of people. So when I’d been living in London for a number of years, enjoying some success, I met a greater variety of people. Not just in England but around the world. Sometimes you’re quite fortunate, being on the stage, getting to meet people like Salvador Dali.

(Shortly after meeting Dali, in fact, Bryan Ferry dismissed him as "someone who hangs around with bands just to get publicity." I don’t say anything.)

BF: You start thinking of the world as a place full of all different kinds of people, rather than one particular class of people. Much as I love the northeast, I didn’t want to spend my life there. I wanted to experiment. Savour everything you can while you’re here! Touring, seeing the world… That in itself gives you a different perspective.

Words, floating. I’m trying to get through, but… yeah. I alternate between questions and suggestions, hoping for some kind of unusual or slightly stimulating response, but everything just goes ‘thud’ into a kind of velvet wall. I don’t think it’s a game he plays. I’m not sure he’s even aware that he’s doing it, these days. A passer-by would just conclude that there’s nothing there, that this is an ordinary guy, quite cultured and well-read but the kind of person who absorbs ideas, rather than generating them. Fair enough, but this is Bryan Ferry. Moreover, it’s Bryan Ferry in an unexpectedly rich late period, full of experience and old adventures and still right up there, doing it. He’s very nice. But why doesn’t he want to say anything about anything? When all your strangest dreams come true, is this what happens? I’m almost glad I’ll never know.

Compared to most well-known musicians – who give so much of themselves, whether you ask them to or not – I don’t think people have much idea of what you’re like as a person, Bryan. Emotionally, and so on.

Bryan smirks. He doesn’t smile, he smirks.

BF: Ha ha ha… They haven’t a clue.

Does that surprise you? Or is it entirely deliberate, this vast distance that you keep?

BF: I dunno. It all seems to be accidental to me, how an image builds up.

Oh really?

BF: One thing leads to another. Just the fact that I was interested in clothes, but not obsessed with them – a more than average interest, perhaps. But I grew up in Newcastle, which is a very clothes-conscious place. I always think of it as a bit of a mod town, really. And also I worked in a tailor’s shop on Saturdays. And at the beginning of Roxy one of my best friends was Antony Price, who helped us a lot, and enjoyed having us to display his great talents. So the clothes thing, the visual stuff that we did, we just thought it was a bit of fun really.

(Do you think Bryan’s being slightly disingenuous here? I don’t say anything. What would be the point?)

BF: But after a year or thereabouts, all these strange Top 20 groups started copying the clothes we were wearing and it all became a bit weird, so I started wearing suits as a reaction against that. So people started thinking, Oh, suits – he thinks he’s a gentleman!

(I definitely think Bryan’s being slightly disingenuous here, but I don’t say anything. What would be the point?)

BF: And the fact that I’m quite shy and conservative in my demeanour anyway, I started being singled out as quite unusual in the job that I do. I wasn’t going to start chucking TVs out of windows or anything like that.

(Back in the sextastic, deeply drugged and now almost unreal 70s, asked what the super-sleazy, devilishly decadent Roxy got up to when their gigs were over, Ferry thought for a moment and said, "Well, usually, we go out for a meal.")

BF: So an image builds up, and some of it’s true and some of it isn’t. So you have no real control.

No control? That’s rather strange, I think to myself. Bryan Ferry, after all, was one of those first few rock stars to discover that you can in fact control your image more closely and carefully than anyone had previously thought; you can use it as a tool, to jemmy open locked doors and get what you want. Then it strikes me that I’ve asked him about what’s behind the image and he’s talked about the image, which I suppose you could interpret in one of several ways, couldn’t you? But I don’t know. I haven’t a clue. I’m trying to get through. What would you do?

Cross-channel Ferry: Bryan bakes a hash cake while speaking English, in Petit Dejeuner Compris

Umm, can we talk about something trivial?

Bryan stares through me, by this point longing for a well-deserved bed, but he assents, and whatever – we talk about something trivial. Just for fun. Just to see what happens.

Someone showed me something interesting recently: an episode of a French TV show called Petit Dejeuner Compris…

BF: Oh yeah!

What happened there?

BF: It was a kind of series, I dunno, I was only in one episode, I think. It was about some bourgeois Frenchwoman from the provinces who inherits an offbeat hotel in Paris. So that was where the title came from, Petit Dejeuner Compris – ‘Breakfast Included’.

Starring Bryan Ferry. How come?

BF: Because the woman who wrote the series was Danièle Thompson, a very good scriptwriter – she wrote La Reine Margot, a really good period film. And her husband was a famous rock promoter in Paris called Albert Koski, and he was my promoter. That’s how I got involved. I think I check into this hotel, and she comes to see my show. I don’t remember the rest.

In the grand scheme of rock stars acting, you weren’t too bad in it.

BF: Oh, I was terrible! Shocking! I’ve never seen it since, though.

It’s on Youtube, if you fancy it. It’s quite funny.

BF: Oh no – please!

What about Jazzin’ For Blue Jean, the long-form video for David Bowie’s single ‘Blue Jean’, from 1984?

BF: Ah no, I’ve never seen that…

Well – it’s not funny, but it’s supposed to be funny – Bowie plays this geeky guy who’s trying to impress a girl, and he’s got a very suave flatmate who looks down his nose at him.

Bryan chuckles suavely, a faint smile building.

BF: Oh…

And – you can guess where this is going, can’t you? – it’s a parody of you. He’s got the hair and the suit, and he’s reading a copy of Country Life magazine, just in case anybody didn’t get it.

BF: Oh my God! Really? How funny! If I ever see him, I’ll pull him up on it…

That’s online too. Have a look.

BF: I never do that, I always forget you can do that, with Youtube and so on. People tell me, "You must see this," and I say, "Oh really?" I don’t even know how to download things. I’m a bit of a luddite, I’m afraid.

Suddenly, Bryan Ferry is smiling and laughing and relaxed. I’ve stopped asking him things. The ice has melted! The champagne bottle is standing up, untouched, in lukewarm water. Now we can have some fun.

"Thanks!" he says suddenly. There’s a pause. And he shrugs, almost apologetically. "Got to save my voice." And that’s the end of my interview with Bryan Ferry. I glance down at the timer on my recording machine. Implausibly, I’ve used up 40 minutes of Bryan Ferry’s life. Where did it all go? It feels like no time. No time at all.

Two people in a very expensive room, floating past one another. He was good company, in a way. Intelligent, impeccably polite. Just, y’know, half there and half somewhere else. But I’m not here to judge. Bryan Ferry has kept himself together – as far as anyone knows – and maybe this is how. I say a breezy goodbye to one of the few musicians I’ve met who I felt I could see more of from a seat at the back of the stalls.

Some people say that interviewing Bryan Ferry is dull. I found it fascinating.

Tivoli Gardens is one of the oldest fairgrounds in the world, a spellbinding space in the centre of Copenhagen (this is almost certainly where Scott Walker’s love, as he sings in ‘Copenhagen’, became "an antique song for children’s carousels"). The Danish heavens have opened, and in the dark early evening I follow a swirl of umbrellas past the bumper cars and the dragon boats and the pantomime theatre, along the gleaming wet walkways to the concert hall on the far side of the grounds. I float through a well-to-do Scandinavian audience, mostly in what might politely be called late-middle age, to a seat at the back of the stalls. And eventually Bryan Ferry slinks onto the stage and opens with ‘Re-Make/Re-Model’, a song which is sort of about chasing a girl, but is really about arranging cultural debris in new and unexpected and amusing formations, to offer yourself a kind of a future (is there a future?) and to prove you exist. Everybody claps along.

Even with sopping trouser-cuffs, it’s hard not to enjoy the upbeat, downbeat sound and spectacle of Bryan Ferry live. Naturally, when they play the old songs you can sense that something’s missing: the booming space which once made up the best part of ‘If There Is Something’ is plugged and deadened, and there’s a politeness to ‘Ladytron’ which probably can’t be helped. But the beaming ponytailed woman on drums is a proper thumper, and the trusty old session man’s bass is bubbly and thick, and by the time we get to ‘Love Is The Drug’ Bryan Ferry is really Bryan Ferry, reproducing that dance routine with the fists-on-hips and the campy wiggling, and there’s nothing self-mocking or distant about it. It’s hard to see this near-septuagenarian doing his thing – and it is his thing – as anything less than wholly admirable, perfectly honourable, just as fine as anything else he might be doing on a wet October night.

It’s just entertainment, of course – something in the corner of a fairground. In that sense at least, Bryan Ferry has moved with the times. But I’m not here to judge. I’m here to listen. And I’m being entertained.

We reach ‘Editions Of You’, still torn in half by that atonal synthesizer break, and Bryan’s still doing the actions. "Look out sailor when you hear them croon," says Bryan Ferry, a flattened hand shielding his eyes, gazing out across the ocean which separates him from people like me… Bits of his own life swept back towards him by the tide, and other bits floating, floating away. "You’ll never be the same again/ The crazy music drives you insane."

Part false, part true, like anything.

Three days later a friend rings.

"Did you meet Bryan Ferry?"

No, I say. Not really. No.

Avonmore is released on Monday