Bernard Butler is in his West Hampstead flat, demoing material for Suede’s eagerly anticipated follow-up to their eponymous first album, the Mercury Music-award-winning, fastest-selling debut since Frankie. Music is pouring out of him at an alarming rate. On the demos, guitar lines are flying everywhere on endless reams of odd, distorted music, music with an almost violent creative streak, music that roars with the joy of creation, music that sobs with real loss and loneliness. All these compositions have one common purpose; to tear up the blueprint that has proved to be such a winning formula for Suede. In the words of future friend and collaborator Edwyn Collins, he wants to “rip it up and start again”.

Aiding him in this are not just his guitars but a drum machine, a piano and a Roland SH-1000 Monophonic synthesiser. His tastes are as catholic as his upbringing, records of imperial audacity like old favourites Joy Division’s Closer and The Smiths’ Queen Is Dead rub shoulders with acts of pop star self-sabotage like Marc & The Mambas’ Torment And Toreros, and buzzkill song cycle Berlin by Lou Reed. Berlin has a closing four-track passage where the most mellifluous arrangements couch the starkest realities. A reaction to the Bowie-assisted success of Transformer, like Butler’s other recent discovery Neil Young, Berlin is avowedly anti-glam. Records like The Righteous Brothers’ ‘You’ve Lost That Loving Feeling’ exert an increasing influence over the virtuoso musician; pop catharsis, titanic orchestrations and a lament for the absence of tenderness in a partnership all wrapped up in a Phil Spector production. Walls of sound are building in Butler’s head as vast as those that have sprung up between him and his bandmates…

The demo tapes are delivered to his co-writer Brett Anderson on the other side of Hampstead Heath in Highgate. A couple of years ago, the two would pen off-the-cuff classics like ‘My Insatiable One’ face-to-face, making use of rehearsal rooms that the rhythm section are too ill to get to. Now they are worlds apart. Nevertheless, there is a fire burning in the pair, to create something extraordinary, strange and beautiful, something sprawling and tortured. They are still determined to impress one another, to usurp one another. Having previously concocted songs which lend themselves to a theatrical sense of performance, they are now devising an album that flows like one huge composition, the majestic movement of an intentional masterpiece.

Anderson’s new residence, a garden flat, 16 Shepherd’s Hill, is partly chosen out of superstition (16 being a lucky number for the singer) and partly to flee the rise of Britpop, a movement to a great extent spearheaded by his band’s meteoric rise. His chronicling of twisted English lives has mutated into something Suede want no part of. Theirs is a lonely world, splintered from within due to internal strife, utterly at odds with the zeitgeist. But while holed up in Highgate, Anderson strives to match his co-writer’s mad ambition via a diet of psychotropic drugs, old movies and a wide array of reading material, ranging from Romantic visionary poets like Blake to prophets of dystopian doom like Orwell and JG Ballard. On the stereo are Pink Floyd’s Dark Side Of The Moon, Kate Bush’s Hounds Of Love and a whole host of crooners and chanteuses, one of them being the baritone voice of Scott Walker, a new musical love he shares with Butler. His worldview widens, his imagination soars, his personal relationships dissolve. But in dreams he’s in the passenger seat of James Dean’s Porsche, encouraging him to go a little faster at the junction of California State Routes 41 and 46. Other Anderson reading material delves into Hollywood and witchcraft. Somehow he thinks the result of all this will be a pop record…

That record will be called Dog Man Star. It’s a title that reshuffles the name for Stan Brakhage’s short films, Dog Star Man. The alteration is important. Dog Man Star rolls off the tongue with ease, suggesting a trick, a spell, the wave of a wand. It has the upward sweep of Anderson’s ascent, dragging himself from council home to stage. It will be a record about ambition. But it will be a record all about falling apart too.

Above Anderson, hymns seep through the floorboards, sung by the Mennonites, a Christian sect that rejects the modern world just as his band have rejected recent musical developments. A stone’s throw away to his right is the local library where he acquires all his current reading material. Further right, across the road and up the hill is Waterlow Park, where he penned the lyrics to ‘Sleeping Pills’ before he was famous. Highgate Cemetery contains Karl Marx, the corpse of revolution in this leafy, affluent North London enclave. But living, breathing anarchy bides its time down the hill in Archway, a sharp dose of urban reality, threatening to trample over Highgate’s ‘Village Green Preservation Society’ idyll at any point. Or at least that’s what Anderson thinks. Who knows? He’s finding it hard to leave the house these days.

Much closer to the centre of the city, producer Ed Buller is having lunch with Flood at Joe Allen’s on Covent Garden’s Exeter Street. It’s the favoured eating destination for the district’s theatre goers, with its subterranean dining room, its exposed brick walls adorned with pictures of Liza Minnelli et al and its elegant crisp white tablecloths. Buller is confiding in his colleague about the friction that has come to characterise the mood within Suede’s camp. He senses that the record he is about to produce will be the last one, at least from this current line-up. Ever the optimist, Flood predicts that, in all likelihood, the record will be amazing. They are both right.

From the moment Brett Anderson and Bernard Butler started to hone their songcraft, the seeds of Suede’s second album, Dog Man Star were being sown. “It was always an album we knew we could make,” say Anderson now. Early compositions like ‘Pantomime Horse’ and ‘The Drowners’ B-side ‘To The Birds’ are supremely confident structures, swelling to operatic climaxes, shifting gears like mini-symphonies. On ‘Where The Pigs Don’t Fly’, the stop-start intro has an almost regal sense of presence. This was music with poise and purpose, music that demanded to be heard by a band that demanded to be seen. Onstage and in song, the pair had forged an almost telepathic, brotherly bond. According to Butler’s recollections in John Harris’ The Last Party, they smoked the same cigarettes, dressed identically, the concerned Butler would accompany Anderson home on the tube.

In July 1993, four months after the release of their debut album, Suede teamed up with Derek Jarman for an AIDS benefit at the Clapham Grand. The show was their most lavish spectacle yet, augmented by cellists, piano and guest singers Chrissie Hynde and Siouxsie Sioux. Behind the band, the director’s Super 8 images flickered. Jarman had made visuals for Suede’s forebears, The Smiths and the Pet Shop Boys (both of them included, along with The Commotions on the Melody Maker ad Butler originally responded to). This wasn’t a gig. It was an event, the gesture a band entering an imperial phase would make. Their next release would be an eight-and-a-half-minute stand-alone single, ‘Stay Together’, that came wrapped in a gatefold sleeve. But just as Suede were ascending to that rarefied realm where commercial success keeps the company of ‘high art’, they started to fall apart…

Brett Anderson is hedonistically lapping up the shirt-shredding adoration that Suede are receiving in Britain and beyond. Like bassist Mat Osman and drummer Simon Gilbert, he is enjoying success. Anderson has gone from taking the occasional E and smoking the odd spliff to being quite a serious user. Crucially he sees a link between drugs and his songwriting. Bernard Butler, on the other hand, is panic-stricken, fearful of fame, irritated by the music biz treadmill and the clichéd rock star excesses his bandmates are indulging in. He’s also increasingly confused by the Brett Anderson character he reads about in Suede’s press.

As Suede tour the world, Anderson and Butler’s ideas for the band get bigger, just like the gap between them. Anderson hears Buddhist monks chanting in a Kyoto temple and decides he wants to summon a similar hypnotic sound to raise the curtain on Suede’s second album. Butler road tests new material at soundchecks, the booming sound of the riff and the drums fills empty halls. It’s a brutal beefy thud that he wants to recreate on the next Suede album. A visceral thump to the punch-bag of Suede’s public image, a fatal blow delivered to the debut’s top-heavy sound. It’s a raw, live noise that will tear through quiet songs and overdub-rich textures. Outside of the studio, those empty halls are the only places that will hear Butler play Suede’s new song.

As Suede embark on a second US tour in September 1993, tragedy strikes. Butler’s father passes away. He flies home for the funeral and then swiftly, insanely, returns to New York on a tour that, all will later agree, should be cancelled. Grief-stricken and missing the domestic anchor of his girlfriend, he moves further away from his bandmates. Too young, too drug-addled and too English, Anderson fears that trying to console Butler will only further damage their fragile relationship. Haunted by his own recent loss of his mother, he looks away. Butler travels with the road crew, gets stoned and composes continuously. Unbeknown to him, Anderson is writing furiously too, and onstage, Anderson and Butler are increasingly competitive. In New York, their last US gig is such a ferocious display of one-upmanship that only one record company representative dares approach them backstage.

Meanwhile back in London, Britpop has been gathering momentum since Anderson appeared on that Select cover superimposed onto a Union Jack with a not-so-graceful ‘Yanks Go Home’ headline. Suede’s touring has opened them up to broader vistas, from Kyoto’s chanting monks to Tinseltown’s casting couch atrocities. When their arch rivals Blur tour America, it concentrates their focus on a ‘British image’ (the mid-60s US blacklisting of heroes The Kinks triggered a similar Anglo-centric shift). Former Suede member Justine Frischmann has formed a new band, Elastica. ‘Car Song’ drives home the difference between her new music and that of her old band. An angular, perky two-and-a-half-minute backseat romp, it contrasts starkly with ‘She’s Not Dead’s languid foreplay, it’s motor tragedy romance.

Further north, in Sheffield, Pulp’s Mike Leigh vignettes meet the steel city’s synth heritage in increasingly poppier forms. In Manchester two brothers are fronting a band called Oasis. Noel Gallagher hears ‘Animal Nitrate’ on the radio and is galvanised to pen ‘Some Might Say’, a future number one. Oasis’ logo is the swirl of the Union Flag; the Roses’ abstract expressionism simplified to embody a new national pride. By the end of 1993, Anderson stares out from the cover of the NME accompanied by the quote/headline: ‘England Drives Me Nuts’. There are no Union Flags behind him, and there will be no songs about chip shops on Dog Man Star

In September 1993, while Butler’s father was dying, the band recorded ‘Stay Together’. The first half was a radio-ready serenade, an ode to lovers embracing in the shadow of apocalypse. A disco-falsetto chorus and Butler’s relentlessly chugging guitar pierced the hazy dreamscape sonics, replete with saxophone and rising notes on a Moog. The second half was an extended outro, in Butler’s words, “a tunnel going deeper and deeper”, a grandiose next step after ‘He’s Dead’s climactic carnage, a multi-tracked outpouring of grief.

In many ways ‘Stay Together’ was Butler’s baby. He channelled all his pain into its recording, spending hours in the studio. Amid the turmoil of the American tours, Butler had discovered Neil Young, via a copy of After The Goldrush. The peripatetic Canadian represented everything Suede’s public image stood in stark contrast to, and Young’s overdriven guitars, ample use of vibrato, his careening between brutal noise and fragile prettiness mirrored his own contrary creative impulses. Young also had a habit of exiting bands.

If the pair were in Anderson’s words, “like two Siamese cats, fighting, two halves of the same whole” then the guitarist had the upper hand in this power struggle, the music took over. This posed something of a problem to the band’s internal dynamic, according to Buller. “When the singer isn’t singing, how do you justify the music? It all comes down to a band disagreeing about whether the singing should stop,” he says now.

Despite Anderson’s misgivings, the single sailed to number three, their biggest hit thus far. True to form, ‘Stay Together’s flipsides were triumphs, both the elegant acoustic form and junkie lyrical content of The Living Dead’ and the radiant hymnal ‘My Dark Star’ emboldened Anderson and Butler. “We could make a beautiful, heartfelt album of songs like these, rather than one full of ‘Metal Mickeys’,” says Anderson.

By the time of its Valentine’s Day 1994 release, ‘Stay Together’ was an old record, and writing was already well underway for Dog Man Star. Anderson talked about “the recording artist as lunatic”, the insane, inventive immersion in studio craft that had expanded rock’s vocabulary. Close to Butler’s heart was Martin Hannett, whose Joy Division productions weren’t live documents but clinical studio separations of sound – literally. He subjected Stephen Morris to playing each constituent part of his drum kit in isolation. Butler would work out the emotional force of a song with drummer Simon Gilbert for endless rehearsals – terse exchanges and thrown drumsticks eventually ensued.

Part of Butler’s impatience stemmed from his eagerness to get a constant stream of ideas onto tape (“I’ve got music going through my head all the time” he said at the time) before they were forgotten. Moving onto synths he was exasperated by the time-consuming programming of the Buller Moog and instead purchased a Roland SH-1000. “He put it through pedals and got great sounds out of it right away. He was so inventive that way,” says Buller. “He had two ideas going through his head, the song and the soundtrack.”

Behind the closed doors of 16 Shepherd Hill, things get curiouser and curiouser. Brett Anderson is re-reading Through The Looking Glass by Lewis Carroll, the author of metamorphic fairy tales, the writer of drug-dream fantasies. Proto-psychedelic, Carroll’s writing would heavily influence much of the 60s’ most hallucinogenic music, The Beatles’ ‘Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds’, Pink Floyd’s ‘Julia Dream’ and Jefferson Airplane’s ‘White Rabbit’, all music Anderson is fond of. Much of Anderson’s new songs, like ‘Asphalt World’ and ‘Black Or Blue’, send autobiography down the rabbit hole of Carroll’s beguiling narratives. The grit of twisted E-fuelled love triangles, failed romance and racial tension get an otherworldly spin that perfectly blends with the more sensual music coming through the post box. Suede’s new album will open with a very Carroll-esque flourish: “Dog Man Star took a suck on a pill/ And stabbed a cerebellum with a curious quill”. The couplet also suggests a Crowleyan invocation. Crowley’s diabolical charisma predicts “the magus-like power of the rock star”, something Anderson already partly possesses. But he hankers for more.

On another new song, ‘Daddy’s Speeding’, he takes Carroll from Alice In Wonderland to James Dean in Hollywood Babylon. Carroll’s drug-dream collides in a car with Ballard’s Crash, Anderson’s “green fields” and “death machines” evoke Ballard’s modern, barren landscape. There’s also a bit of Kenneth Anger’s infernal expose on Tinseltown thrown in too. Unsurprisingly, Brett has added acid to his usual diet of drugs – the heaven and hell drug, the opener of perceptual doors, the most un-Britpop of narcotics.

He’s also dipping into Blake, the Romantic poet-seer whose ‘visions’ of a divided self, of a divided nation inform his writing. Blake’s lines like, “With Sorrow fraught, My notes are driven; They strike the ear of night/ Make weep the eyes of day,” are echoed by ‘Daddy’s Speeding”s “Sorrow turns his eyes to mine/ Sorrow breaks the silent day”. And The Tyger‘s “water’d heaven with their tears” runs through Brett’s “the tears of suburbia drowned the land”.

On a more general level, Blake’s Songs Of Experience tapped into England’s blighted underclass as Anderson’s new writing frequently does. Throughout Dog Man Star, there’s a feeling of an impending riot, of centennial destruction, of the disenfranchised rising up. ‘Introducing The Band’s “let the century die to violent hands!”, the next song ‘We Are The Pigs’ goes into the “eye of the storm”, a blazing snapshot of a world aflame, of “waking up with a gun in your mouth”, of “police cars on fire”. To Brett, the future is a brutal place, the Orwellian vision “of a boot stamping on a human face forever”. For ‘We Are The Pigs’, Anderson borrows some of the bestial imagery in Orwell’s Animal Farm.

The terror that is around the corner in Anderson’s new writing could be the vivid undercurrent of violence that sweeps a nation still rife with inequality after years of Tory rule. Or it could dwell inside the mind of a man afraid to leave the house, afraid of who’s knocking at the door. For some time, the singer has been living in a house of cards, a place of decadent excess that he uneasily senses could crumble at any point. There’s the instability of his psyche, of Suede’s success, of his relationship with his co-writer. On ‘This Hollywood Life’, the narrator asks to be rescued from the rock star life of hollow decadence. Anderson didn’t have to travel as far as California to witness such depravity, it was happening all around him.

Anderson identifies more closely with figures in movies than those in the real world. A star onstage, his dissolving relationships offstage spin him into an alienated orbit. He turns to the silver screen for company, like the hormonal teenager who can only connect with pornographic images in his new song, ‘Heroine’ which rides in on a line from Byron. Anderson watches Performance on a daily basis, transfixed by the collision between the reclusive rock star, Turner (played by a real life one, Mick Jagger) and runaway gangster, Chas.

Dog Man Star will be the most cinematic of records, peopled with James Dean, titles borrowed from Brando flicks, it even uses Marilyn as a Venus/Aphrodite archetype on ‘Heroine’. Butler’s music will be his most visual yet, “a song and a soundtrack”, as Buller observed. Hollywood will worm its way into the album in the most random way. Both Anderson and Butler play movies in the studio, a constant backdrop, and a chance switching of a TV channel at the end of ‘The Asphalt World’ reveals the voice of Lauren Bacall in Woman’s World, a 1954 Technicolor drama.

Such heartstring tugs, such grand gestures reflect a band unafraid to think big. As weird as Anderson’s lyrical ideas are getting there’s also the desire, the ambition to write an American number one, to pen that evergreen anthem that sweeps the airwaves of daytime radio, a big broad stroke of genius that buries itself deep into the hearts of the kind of people he writes about. A song for lovers to marry to, a song to transport the housewife away from the drudgery of the everyday. It’s a song he always tries to write. One day he succeeds. After he writes the top line and lyric to ‘The Wild Ones’ he walks around Highgate in a gleeful daze. The only problem is that Butler wants to drag it from the realm of the morning show and into the outer limits with an extended outro that sticks Anderson through a Leslie cabinet.

Anderson’s new writing is rife with contradiction, just as Butler’s music zig-zags between euphoria and woe. The push of his acid-expanding imagination and of seeing new continents merges with the pull of old Suede themes and Anderson’s past, of suburban graves and housewives waiting by windows. No matter how far through America and Europe ‘Introducing The Band’ travels or how “far over Africa” and “endless Asia” ‘The Power’ glides, there is that inescapable impact of the suburbs on the English psyche. “Don’t take me back to the past,” Anderson had begged at the end of ‘Stay Together’s rant, but it is forever present on Dog Man Star.

In order to incorporate these paradoxes, Brett’s lyrical viewpoint becomes increasingly fractured, often echoing the cut-up techniques devised by Brion Gysin/William Burroughs and adopted by Bowie on much of his post-Ziggy work. Anderson’s own cut-and-paste style, most notable on ‘Introducing The Band’ and ‘Killing Of A Flashboy’, processes the overabundance of cultural, chemical and geographic stimuli he has absorbed since Suede’s rise. It’s the only way to spew out his chaotic world, which he does with free association lyric sketches on Suede’s new demos. It’s an approach that uses words for their phonetic, rhythmic potential and to paint images, rather than generating specific meaning. His subconscious takes over. Dog Man Star‘s dramatic shifts, between ultraviolence and tenderness, high romance and isolation, evolution and disintegration, ambition and implosion make it feel like one giant cut-up of human emotions. All somehow flowing like one giant song.

Rehearsals for Dog Man Star took place at Jumbo. The music represented a huge leap from the debut, scaling new heights of musical and emotional expression. There were problems. The driving Pretenders/Blondie rhythm of ‘New Generation’ wasn’t as good a time to make as it sounded on record, indicative of worsening relations between Butler and Gilbert. Even more contentious was ‘The Asphalt World’, conceived at least initially, as an Echoes-style side stealer, Butler’s furthest flight yet from the pop three-minute discipline, an odyssey into different musical time zones. Allegedly it boasted an 18-minute instrumental passage. Butler now contests this, claiming he always intended to make edits.

By the time the band entered Master Rock Studios in Kilburn on March 22, Butler was operating on a completely different time shift to the more nocturnal Anderson, coming into the studio from 9-5. In order to ensure Butler was comfortable and able to lay down his constant flow of ideas to tape quickly, a room with two couches, lamp, TV and carpet was created, an informal set-up predictive of the set-up in the musician’s own studio later on.

Both Anderson and Butler had immersed themselves in Scott Walker’s largely Wally Stott-orchestrated Scott 1 – 4, records which moved further and further away from the top of the hit parade and deeper into an existential, self–penned loneliness. Walker’s people sang silent songs and dreamt all day just like those in Anderson’s. One album of Walker’s was a particular Anderson favourite, his third, which included not only ‘Big Louise’ (“guaranteed goosebumps,” says Anderson), but more interpretations of Jacques Brel songs, one of which, ‘If You Go Away’, would directly influence ‘The Wild Ones’.

Dissatisfied with the sound of his voice, Anderson delved into the crooners and chanteuses who “had the musical and emotional range to turn a song into a drama”: Walker, Sinatra, Piaf. His vocals already hinted at an inner torch singer. Now, these, the most ‘singerly’ of singers would trigger a move away from strangulated cockney, what producer Buller calls his ‘Tommy Steele’ voice, to honing a more deep and rich tone. Listen to the booming intro of ‘The Wild Ones’ and you get the same goosebumps Anderson got from hearing ‘Big Louise’, a vocalist in total command of their instrument.

Most startling was the voluptuous, stuttering falsetto of ‘Black Or Blue’, the album’s hidden highlight. Buller recollects his first listen to the vocal as a definite peak in his production career, “From hearing Bernard’s chords, in no way did you expect that. What was it? It wasn’t pop music, it was more ambitious. It was like Ravel, that vocal melody”. Few singers of his generation, certainly none from the indie background were taking such risks with their vocal chords. And certainly none had the chops to rise above a 40-plus orchestra as Anderson does on ‘Still Life’. Butler lays down a backing track that’s 60’s floaty baroque, all mellotron and dulcimer cascades (Andrew Cronshaw) , a faux-orchestral descendant of Nitzsche’s Buffalo Springfield/Young’s arrangements, Walker’s Montagu Terrace. In Anderson’s hands ‘Black Or Blue’ becomes a little more fruity, partly Brel chanson but perhaps most akin to Prince’s ‘Condition Of The Heart’, a song that like ‘The 2 Of Us’ talks of how “money buys you everything and nothing”. Combined ‘The Power’ and ‘New Generation’ showed a titular Prince influence. On ‘Black Or Blue’s punch-drunk cabaret it goes deeper, a pirouette in the face of NME-reading, Britpop beery orthodoxy (the line “I don’t care for the UK tonight” made that clear). This was Broadway–bound; Romeo & Juliet-esque tragi-romance, not Reading Festival fodder.

These performances showed a total commitment to singing, to experimenting and matching his musical partner’s, his co-star’s audacity. In the studio Anderson would get in character, spending hours perfecting the intonation of the title in ‘Daddy’s Speeding’ until the second word sounded like a “silver car accelerating”. Even the singing was trying to be seen.

Separate their lives may be but Anderson and Butler are still having conversations with one another through song. Anderson hears Bernard playing a sad piece of music at the piano. It’s the sound of someone working their way through loss as their fingers navigate their way around the keys. It’s beautiful, moving, daunting. Somehow Anderson has to grace the music with words that can do it justice.

It becomes ‘The 2 Of Us’, one of those ‘lonely at the top’ lack-of-love songs. For the singer it is set in the world of high finance/lost romance, a song sung from the point of view of the “lonely wives of the business class”. It’s about the divide that opens up between people once their dreams come true. It’s the worm in the bud of Dog Man Star‘s ambition, the rot of personal relationships in the face of success, of being “alone, but loaded”.

As ‘The 2 Of Us’ builds, its elegant mask slips. The song-inside-the-song gets louder, piano and drums nag like a memory. The narrator calls out to her estranged partner in vain, “through the rain”, singing a silent song. In the “prison of a house…the illness comes again”. She could be the housewife in ‘Sleeping Pills’ in a grander house, she could be Brett Anderson in 16 Shepherd’s Hill. It’s the most communicative of songs about the inability of humans to communicate, made by people who are barely talking to each other. It swells to a show-stopping finale, sobbing into its pillow as grandly as Lou Reed’s ‘Caroline Says II’. Once again, Brett rises to the challenge of the music, penning a song where the middle of the road meets the ditch of despair, like Radio 2 uneasy listening. The Carpenters’ ‘Rainy Days And Mondays’, Don Mclean’s ‘Vincent’ and Nilsson’s ‘Without You’, but with the chill of The Smiths’ ‘Asleep’ blowing through it.

And ‘In each line lies another line’: a song within a song, a subtext within a subtext. The record the narrator hears in ‘The 2 Of Us’ is The Beatles’ song of the same name on their last release, Let It Be. It is seemingly a song about lovers ‘on their way home’, the bridge looking back reflectively at the characters’ shared experiences. McCartney’s recollections of happier times with his estranged partner Lennon come to the surface. A fond farewell to a dissolving musical partnership, it’s veiled in the safety net of a love song. On the demo for Suede’s own ‘2 Of Us’, guitars go backwards, Revolver-style. Elsewhere on that ’66 album, ‘For No One’ speaks of a “love that should have lasted years”…

A glance at the tableaux on Sgt. Pepper’s cover reveals figures that crop up on Dog Man Star, directly or indirectly; Brando, Carroll, Marilyn, Crowley. Even Dog Man Star’s structure (the purpose-built prelude ‘Introducing The Band’) echoes Sgt. Pepper’s with its overture.

The concept of a studio band replicating a live show was also on Butler’s mind, a man who loved the stage just as much as he loathed touring (like The Beatles who similarly retreated into the studio). ‘Introducing The Band’ is a dank approximation of psychedelia. It opens with a throbbing revolving noise, the sound of the biggest record on earth spinning before the needle’s dropped, the sound of that monstrous piece of vinyl in The Human League’s ‘Black Hit Of Space’. A beatbox loop ceremoniously kicks in from Butler’s original demo, a bass line pulsates, ambient synth noises trickle. Then Bernard’s guitars enter, a monochromatic sharpening of McCartney’s sitar-like runs at the fade-out of Strawberry Fields Forever. It’s the sound of 1967 frozen over with European froideur; Pepperland meeting the solemn architecture of Joy Division’s Closer. Anderson begins his mantra in a voice that’s part Future Legend doom prophet, part Magical Mystery Tour MC. Dense, free association wordplay conjures images of sex, violence, drugs and the creative process , all wrapped up in a fanfare for a mutant band taking to an imaginary stage. Scenes from Performance flicker through the lyric; the chic thug, the whip-cracking, the blood, the gun. But as the tribal beat continues, and as Anderson’s chant imperiously asserts in the singer’s words, “the unstoppable force a band could become” a sampled loop rips through the fabric of of his perfect vision.

“I’m dying” it seems to say over and over again, like an utterance from the Tibetan Book Of The Dead. Even at the beginning, the end is nigh, as Anderson’s increasingly apocalyptic lyric acknowledges (he also references Winterland, the Pistols’ last stand, another band with combustible energy). It’s the perfect curtain-raiser to Dog Man Star’s ambition/disintegration; the sound of a band scaling new heights, clamouring for a world stage as they are imploding and getting odder than ever. It’s the terror of the sublime, the roar of modernity that slices the eyeball in Bunuel’s film, Un Chien Andalou, the mechanical beast stampeding Max Ernst’s painting, Celebes.

One song that didn’t make the final cut and should have was ‘Killing Of A Flashboy’, a ‘We Are The Pigs’ flipside that incorporated the band’s experiments into a rocker. It’s a red-leather-booted droog rocker, the metronomic thwack of a beat and a savage riff put the violence back into A Clockwork Orange that Ziggy took out. Later Anderson would court ridicule with his random rhymes and nonsense free association, but here he gets it right, all ‘heavy metal stutter’, ‘killing machines’ and fake tans in aerosol land; painting images of violence in lurid comic –book colours.

A live favourite, the studio version features a phased middle eighth, a transmission from “aerosol land” where “Athena loves your body” as invitations to murder and thoughts of the sea mingle. Amid the absurdity is a ‘straw dog’ view of celebrity. Taken with ‘Daddy’s Speeding”s James Dean’s death scene and ‘This Hollywood Life”s jaded fame-game, it complicates the notion that Brett was merely enjoying the ride. He was an instant icon in a country that either worships a show off or wants to throttle them. ‘Flashboy”s “shitter with the pout” could have well been the Anderson’s image in fame’s cracked mirror.

The album’s cornerstone was ‘The Asphalt World’. It’s the chief culprit for the album being retitled Prog Man Star, far less a swipe now than it was then. It wasn’t just Butler that was moving in this direction. Both Dark Side Of The Moon and the second side of Kate Bush’s Hounds Of Love had been Anderson favourites for some time; songs that segue into one another, English music that travels and seeks to bridge the communication gap between humans.

‘The Asphalt World’ was Anderson/Butler’s trajectory to the stars reaching its destination, a labyrinthine epic that takes Anderson’s real life love triangle on an interstellar musical flight. An organ trawls the red light district’s dirty streets, like The Doors sound-tracking Taxi Driver. Gilbert’s drums, a real standout, the result of a tense session with Butler, pound like footsteps descending into the underworld. Butler’s guitar prowls stealthily like a panther licking its paws before going in for the kill. It’s sad, slightly sleazy, slightly sinister. The title of John Huston’s 1950 noir The Asphalt Jungle, an early Monroe film, gets slightly altered. Adding to the b-movie mood is that Buller reverb, aurally replicating chiaroscuro.

Out of this fog-drenched mise en scène comes Anderson’s skeletal passengers riding in the backseat of a taxi to “the ends of a city”; pill-popping Londoners recast as hard-boiled vampires. By the second verse, his iceman delivery thaws and the plot thickens (“she’s got a friend / they share mascara / I pretend”). Butler’s storm-tossed guitars evoke memories of The Beatles’ last days, those arpeggios full of regret. By the time the characters have reached “the winter of the river”, the poetic words, the searing vocal and the relentless music achieve a kind of transcendence , all seem entwined, to quite dizzying effect. This was the fulfilment of Butler’s “elated, sad, sensual, poised” music ; the antithesis of Parklife‘s impeccable cynical sheen.

Both Anderson and Butler sailed to new height on ‘The Asphalt World’. Butler’s guitar work was his finest yet, multi-faceted but aware of its place within the song, knowing when to recede and when to attack. And Anderson’s lyric was a triumph, a storyteller’s grasp of detail and suggestion. His vocal was one of immense power, switching from iciness to full throttle heartache with ease. Singing for a song about sexual jealousy was committed to tape after hearing of a different kind of betrayal.

The song opens up into an instrumental passage. The astral sadness of Eddie Hazel’s 10 minute solo on Funkadelic’s ‘Maggot Brain’ comes to mind. It grows increasingly fraught, psychotic even. Butler’s wah wah gets volcanic, like Marr’s ‘The Queen Is Dead’ at full speed, Phil Manzanera’s bug-eyed Ladytron wig-out. Bernard wasn’t singing through his guitar anymore, he was screaming. Then the song explodes into another dimension, as transporting as that bullet entering the brain in Performance, or the Star Gate sequence in 2001. It’s the sound of the bon viveur being swallowed by the black hole, like the decaying elegance at the end of each side of Roxy’s For Your Pleasure. Anderson’s love triangle becomes the Dark Side of The Moon prism. It ends with explosive noise, changing tv channels; a postscript as avant-garde as The Beatles’ ‘Revolution 9’.

The pressure has been building inside of Butler throughout the recording of Dog Man Star. The pressure to get his musical ideas onto tape, the pressure to destroy Suede’s original vision and replace it with something mind-blowing, the pressure to replace that music Blur are making with something void of irony and full of beauty. Everything around him is a compromise; the producer keeps telling him what to do, his bandmates can’t make the sound he hears in his head. He almost resents anyone playing or singing on top of his symphonies. He feels like he is “on the edge of the cliff, knowing he is going to fall”. He doesn’t want to let go of Dog Man Star, he wants to make a grand exit.

Butler talks to Vox magazine about his dissatisfaction, it creates tremors in the Suede clan but it triggers an immense Anderson vocal for ‘The Asphalt World’ and breaks the silence with his partner. The interview might have even been a last ditch attempt to initiate a dialogue with his old friend. Anderson and Butler resolve things and agree to get back to conquering continents. Things break down again, he issues an ultimatum to Anderson that either Buller goes or he does. Buller has become another barrier to Butler’s musical goals. The more technically aware he has become , the more resentful he is of the producer’s work. Part of Buller’s role has been to mediate between Butler and his bandmates, to protect their interests. There’s talk of Chris Thomas mixing the record, whose CV includes The Beatles, Roxy Music,The Pistols and The Pretenders, all of them Suede signposts. Feeling cornered, Anderson calls his bluff. Buller is not Butler’s real problem, he senses, being in Suede is. Shortly after Bernard marries, he leaves Suede.

The wind howls. A door slams. Everything explodes into silence like the end of one of Dog Man Star‘s unfinished masterpieces. The remaining members of Suede breathe a collective sigh of relief and take the brass section through a rendition of ‘The Girl From Ipanema’.

Dog Man Star had to be finished without Butler. There were some overdubs he laid down at Konk, due to contractual obligations, although Buller now doubts that these were actually used. Parts of it benefitted, for sure. ‘The Wild Ones’ had its extended outro removed. Anderson and Buller made a loop of the singer’s plaintive chorus refrain, glued it together with piano overdubs and faded the song out. It poppified the tune and a similar Butler outro felt far less bolted on when ending ‘You Do’, his single with David McAlmont.

Unencumbered by the second half, ‘The Wild Ones’ is the best of Anderson and Butler, the former’s favourite Suede moment. His booming intro is accompanied by Bernard on a glistening dobro, recorded outside atop his dad’s old car. Singer and the song move centre-stage, delivering a ballad whose tuxedo strings and jet-setting lyric blows the cobwebs off the gothic grandeur elsewhere. It’s a luxurious yearning pop song (Roxy’s ‘Oh Yeah’, ABC’s ‘All Of My Heart’) with the dust of cosmic American music on its heels, even Dire Straits’ ‘Romeo & Juliet’. “It’s the one that got away,” says Buller now, feeling that the song should have been the album’s trailer.

They even experimented on their own, adding Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry dub dynamics to a future B-side, ‘Whipsnade’. But other songs suffered. One, provisionally titled ‘Banana Youth’, had only reached demo stage. The band played it in a circle, a unified entity once more. A session musician was called in to duplicate Butler’s parts. He replicated the notes proficiently but that intangible quality, Butler’s depth of touch was sorely lacking. It’s telling that ‘The Wild Ones’ and ‘The Power’, both seen as light shards shining through a dark record, were themselves more shadowy in Butler’s hands. And they both end with fade-outs where Butler’s songs shatter into silence (again a Buller/Butler difference, the former seeing it as a chance to do something impossible on a stage, the latter seeing it as a cop-out). Its also reflective of Butler’s skill that the demo actually sounds bigger than the album cut, despite a lavish string arrangement.

But it’s a lovely song, panoramic in scope, boundless in its generosity, taking in Asia, fields of Cathay and pebbledash graves, the wings of youth and the entrapped. Starting life as an ode to meritocracy, it’s the happy face of Dog Man Star‘s ambition, of coming from nothing and making something, and inspired by left wing politics. The second verse strikes a sadder note amid the jubilation, speaking of lives lived “for a screen kiss” the unattainable embrace sought by the truly lonely and that “English disease”, belonging to “a world that’s gone”. From an early ‘Pantomime Horse’ draft onwards, “gone” had become something of a favourite in the Anderson lexicon, conflating loss, narcotic oblivion and romantic surrender in one syllable.

This came as Britpop harked back to the glory days of 1966, of World Cup victories and Revolver, of a golden England that only really existed within the prism of culture. You can’t help but think this was all being covertly addressed. Here, however, the tone is wistful, gentle, not reproachful. Perhaps the vision of his father on his pilgrimages to Hungary to collect dust from the grave of composer Franz Liszt’s grave, raising the flag on Nelson’s birthday, softens the focus. In its own refined way, ‘The Power’ points the way forward to 90’s ‘everyman’ anthems, Oasis’ ‘The Masterplan’, The Verve’s ‘Bittersweet Symphony’.

‘New Generation’ on the other hand was, to Buller, a disaster. The stampeding cavalry of those Martin Chambers/Clem Burke drums, a multi-tiered pop attack all made ‘New Generation’ sound like a sure thing. But It was ruined by an abysmal mix, the “worst of my career,” confesses the producer. Later on ‘Trash’ was viewed as the corrective to this wasted opportunity. “The guitars on that track were amazing and they were lost in the song,” he admits. “The tapes should have been handed over to someone else, I was shot.”

The mixing of the album was hastily completed. Buller claims that what exists on the original masters is far superior to what actually emerged. What did emerge sounded subterranean, drenched in that Butler-baiting reverb. Over the years, such flaws become part of a record’s peculiar charm, even becoming the sonic glue that binds it together.

And sometimes it suited the songs. ‘Heroine’s muddy mix, suggesting something that was once luminous has grown slightly mouldy, suited a song about pornography, the gleaming images of perfect skin and lonely, grubby desire. Its lonely youth yearning for pin-ups exists on that continuum of impossible love songs, somewhere along the line of Kate Bush’s ‘Idealized Man With The Child In His Eyes’, The Who’s masturbatory ‘Pictures Of Lily’ and the virtual sex prophesy of Tubeway Army’s ‘Are Friends Electric?’

Butler was also absent for the orchestration of ‘Still Life’. A song that had been conceived during the final stages of the first album, Buller heard another potentially huge hit. In its original form, it was a spare acoustic ballad, a worthy sibling to The Bewlay Brothers and The Smiths’ ‘I Won’t Share You’, swapping Scott Walker ‘s “fire escape in the sky” on ‘Big Louise’ for a “glass house” and “an insect life”. But its tear-stained fortitude reached further than that. Shamelessly sentimental, unabashedly romantic, ‘Still Life’ sounded like an evergreen, a song about a housewife that could be a Housewife’s Choice; pre-Beatles heartbreak, the operatic build of Orbison’s ‘It’s Over’. It was pencilled in for release as a stop-gap single before ‘Stay Together’, closed their triumphant 1993 Glastonbury set, while Bowie waited in the wings. But nobody was quite sure how to arrange it yet. Those Scott Walker records offered some guidance and Walker’s late-period arranger Brian Gascoigne scored the song, conducting the Sinfonia of London’s at Wembley’s CTS Studios. Everybody was overawed by the experience, the sound of a 40-plus orchestra playing a Suede song. This was to be the album’s show-stopping finale, the parting shot to Suede’s widescreen ambition. The song would feature a majestic coda, a final bow, rolling like credits.

Without Butler’s supervision, all agree the orchestration lapsed into the realms of gaudy camp, the coda being the main offender, “filmic but in a clichéd way,” says Osman. “It was an ocean liner we couldn’t turn around,” he says now. Sat at the mixing desk, Buller, complimentary of Gascoigne’s work, nevertheless thought it was a Spinal Tap moment. The sound of an orchestra swamping a fine song and Butler’s guitars (there are loads of multi-tracked interesting noises, most of them barely audible); Sleeping Pills in reverse. Go back to the fleet-footed poignancy of just Anderson and Butler, the acoustic guitar taking flight with the singer’s rising frustration, and it’s hard not to think that something had been lost.

“It’s rarely the things you thought were a good idea that people remember you for,” says Osman now, aware that many love the final version. It is perhaps the only logical conclusion to Dog Man Star, the grand poobah of mid-90s rock. And it’s clichéd sentimentality sounds heart-warming in the context of the thorny company it keeps.

Asked about the prominence of housewives in his songs, Anderson responded that his mother had been one, that he identified closely with the feelings of entrapment and escape conventionally associated with the housewife’s suburban plight. Sandra Anderson, with her strong artistic disposition, may well be the root of Suede’s rich, romantic interior lives confined in drab external circumstances. You can’t help but feel she’s there on ‘Still Life’. But then on that final version so is Peter Anderson, his classical music finally winning the loudness wars with his son’s anarcho-punk blaring upstairs. The final version of ‘Still Life’ took Anderson and Butler right back to the big, sad music of their childhoods.

Some of that anarchic punk spirit resurfaced on Dog Man Star‘s first single, ‘We Are The Pigs’ (the label wanted ‘New Generation’). For someone who later bemoaned the fact that he provided music for a song called ‘We Are The Pigs’, Butler’s pyrotechnic display is the perfect soundtrack to Brett’s riot, with a lightning flash solo tearing through blaring Peter Gunn-style horns, the fanfare of man reduced to animal. The early singles are de-glammed into a tribal stomp, the nihilistic joy of taking a lit match to a cruel world complicated by hymnal sadness.

Like ‘Gimme Shelter’, it’s the rock song-as-tempest, a song that stares at ‘a centre that is not holding’. It combusts with the sound of a playground chant; inner city pressure as a folk horror story, conjuring up images of The Wicker Man, Lord Of The Flies, a ‘dance around the bonfire’. It reached number 18, an underwhelming performance in the ‘top ten or flop’ climate that Suede had partly created.

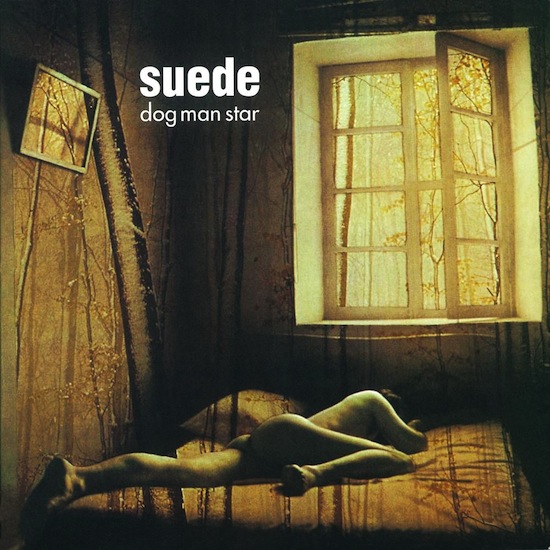

The album appeared in October ’94. It’s sleeve made clear how ‘beautifully out of step’ with the times Dog Man Star was. An original design had been a still from Pasolini’s Salo, a bestial-sexual shocker that was deemed too risqué (‘Animal Nitrate’s sleeve could have been from the same director’s Pigsty). Dog Man Star‘s final images were ‘Sad Dream On Cold Mornings’ and ‘Lost Dreams’ on the front and back respectively, Joanne Leonard’s 1971 photographs.

A nude lies face down on a bed, that place of refuge from the world, of recovery from the last night’s excess, the site of sex and dreams. The bedroom scene’s “mildewy, saturated beauty” (Brett), is both interior and infinite with possibility, like Turner’s house of mirrors in Performance. The world outside is just an open window away, vein-like tree branches bleed into the scenario like a movie dissolve, a deity hovering outside promises miracles. There’s even a diaphanous veil, like the one around Turner’s bed. It’s a fascinating image, not only neatly summing up Dog Man Star‘s sad, sexual vaguely occult-ish world but Suede’s fluctuations between suicidal despair and wide-eyed optimism, the dank squalor and rich romance that co-exists in their songs. The cover’s queasily hallucinogenic, sickly green hues stand in stark contrast to Britpop’s Pop Art redux, sticking out as much as Suede’s early single designs did a few years before (see also the Manics’ Jenny Saville portraits used on The Holy Bible). It looked like Hipgnosis making over Jim French’s ‘Hand In Glove’ cover.

It received largely rave notices, five-star reviews, proclamations of something close to genius, that the hype of Savidge and Best’s PR machine had been justified. Only occasionally did the reception try and shoehorn the record back into the Britpop agenda; “too many songs about James Dean and not enough about James Bolam,” half-quipped Stuart Maconie also drawing a misplaced analogy between The Beatles/Beach Boys transatlantic symbiosis with Suede/Blur’s petty rivalry.

Dog Man Star sold considerably less than the debut and future singles failed to improve on ‘We Are The Pigs” disappointing position. Digs were made about its frequent appearance in second hand record shops, that there was no place for Suede in the playground. But Dog Man Star wasn’t going to the Britpop party anyway. It was staying home and being grandiose, gathering dust, like Miss Haversham condemned to exile when it should have been celebrated, sequestered in its murky mix, a ghost of a band that didn’t exist anymore.

A new band took its place, and Suede, with a 17-year-old guitarist named Richard Oakes, threw themselves into herculean performances, evidencing that Anderson was made of far sturdier stuff than his foppish public image suggested. Promoting the album, Anderson noted how music was not about competition, winning wars or nations, it was about art. He immediately back-tracked. “No it’s about three-and-a-half minutes of feeling great”. The change of heart struck at the tension at Suede’s core.

Suede’s next record, Coming Up, was all about feeling great. What unites the neon-pop ‘Trash’ and McAlmont and Butler’s ‘Yes’ is their collective flight from Dog Man Star‘s gloom and into the top ten. Suede enjoyed their biggest success with Coming Up, a party album with five top ten hits, retrieving some of the razzmatazz and wit of those first two singles but perhaps losing the poetic weirdness that Butler’s “odd, nerdy” music inspired.

Even at the height of Coming Up‘s success, Anderson repeatedly used one word to describe what had gone before: “Untouchable”. And as the years went by Butler made digs that barely concealed the trauma he felt from never taking Dog Man Star to completion. It was the pain of never celebrating music that had been made with a fire that would never quite return, despite his far-reaching achievements, despite making records he was happier with.

But the ending to the story is a happy one. Anderson and Butler became friends again, and worked together as The Tears. Listen to it without the stifling burden of expectation and Here Come The Tears is a tentative step towards brilliance. ‘The Ghost Of You’, ‘Apollo 13’, ‘Autograph’, ‘A Love As Strong As Death’ and b-side ‘Low-life’, were all worthy additions to the Anderson/Butler songbook. Suede, meanwhile, have returned with Bloodsports, their most focused effort since Coming Up, arguably their finest since Dog Man Star.

Almost immediately Dog Man Star starts working its dark powers. In 1995, Britpop’s annus mirabilis, echoes of it appear in the oddest places. Blur’s The Great Escape has songs about loneliness in cars, a Bacharachian piece of orch-pop called ‘The Universal’ with a questionable coda. Pulp’s Different Class has snatches of its Walker-inflected melodrama. ‘Misfits’, ‘I Spy’ and ‘Live Bed Show’ all recall Suede’s world of division outside and lonely beds indoors. “Why Live in the world when you can live your heard?” asks Jarvis Cocker on ‘Monday Morning’, going back further to ‘He’s Dead”s mantra of possibility and limitation “What you do in your head, you do in your head”.

As the Britpop party crashes, Dog Man Star‘s bark gets louder. Fame singes those that were hungry for it, the drugs stop working and people start staying indoors with dirty minds and broken hearts. Imaginations expand. Pulp’s This Is Hardcore, Spiritualized’s Ladies & Gentleman We Are Floating In Space, The Verve’s Urban Hymns are all records with visions Dog Man Star foresaw in its crystal ball. Radiohead’s songs get longer, proggier. ‘Paranoid Android’ notes how “ambition makes you look pretty ugly”, ‘No Surprises’ acknowledges how lonely it can make you too, just like ‘The 2 of Us’. Later on ‘Motion Picture Soundtrack’ will “see you in the next life” while a harmonium wheezes away, the cine-sound of ‘High Rising’ muffled by the mumbles.

And it goes on. The next decade bands form because of the record’s existence (Bloc Party), make studio masterpieces about ‘Still Lives’ (The Horrors) and retain an English identity that travels beyond borders (British Sea Power). Finally it has its revenge on the bigger sellers that bookend it. When reissued in 2011, it sells more than any other Suede remaster, proof of its enduring worth. It sounds better than ever, beefier and brighter without losing its shadowy character, suggesting those at the controls of Portland’s Gateway Mastering had a lot to do with that problematic sound.

When most bands can’t fathom how to rock any differently to Johnny, Joey and Dee Dee, or tug at the heart strings without sounding like they are selling insurance, Dog Man Star is a record Anderson is right to be proud of. It’s a flawed, awkward masterpiece about how flawed humanity is that gets less flawed and less awkward with each passing year. It exists in the universe that favours The Dreaming over Hounds Of Love, Diamond Dogs over Ziggy, Berlin over Transformer, Tusk over Rumours, Strangeways over The Queen Is Dead. Records that never, unlike their better selling or better received brethren, got stale or quaint from success’ over-exposure, that continue to yield treasures. When thinking about some of those records Bernard Butler spoke of their immersive joy. His words apply equally to his own creation, with its outré rockers, its tear-soaked torch songs and darkly glittering epics. So “dive inside, close your eyes, there’s a whole world in there”.