Cyclobe 2014 portrait by Karsten Wolniak

To commune with the music of Cyclobe is to enter not just a strange world, but strange constellations – interdimensional, atemporal zones of carefully cultivated auras bordering wild, unstable forces. Their music parades these deftly contrasting dualities with mysterious, devotional qualities evoked by acoustic folk instrumentation woven through wayward electronic spectra to describe worlds both ancient and embryonic, to explore modes at once elegant and ecstatic.

The last time we caught up with Stephen Thrower and Ossian Brown they were preparing for their first UK show as part of the Meltdown Festival curated by friend and collaborator Antony Hegarty. Their magical, hallucinatory performance saw them expand from a duo into a six-piece to fill London’s Queen Elizabeth Hall with their visionary vibrations. Since then, Cyclobe have performed just twice more: at Norway’s Punkt Festival at the invitation of Brian Eno in 2012 and, more recently, in Berlin as part of the CTM Festival alongside fellow hypnotist Robert Lowe (AKA Lichens).

Following the recent release of their latest album, Sulphur-Tarot-Garden, a new, spellbinding soundtrack to three short films by Derek Jarman, and on the eve of their fifth performance at Poland’s Unsound Festival, they take us ‘behind-the-scenes’ to extensively reveal what constitutes and contributes to their many strange, but always beautiful, worlds.

Hurdy-gurdies

Photo by Karsten Wolniak. (left to right:David J. Smith, Cliff Stapleton, Ossian Brown)

Ossian Brown: Since I first heard the hurdy-gurdy, many years ago now, I’ve been in awe of the instrument. Hearing it performed in recordings of early Baroque music, and becoming excited by a lot of traditional folk, mostly provincial music from central France, I eventually found a marvellous and extremely beautiful Vielle à roue made by Pajot in the mid 1800s. I felt strongly drawn to Eastern Europe, especially Hungarian and Ukrainian folk music, played mostly by peasants, labourers or travelling street musicians. I found the way they played, taking a raw and less ornamental approach, very exciting. I believe the first time I came across the Hurdy-Gurdy was looking at Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden Of Earthly Delights and another early encounter would’ve been M.R. James’s Lost Hearts watching the old 70s BBC adaptation, which has a fantastically chilling scene of a strange blue ghost child playing hurdy-gurdy at the foot of a young boy’s bed … It’s funny that although it’s a lute-backed hurdy-gurdy, the sound they use most certainly isn’t! But despite that, the scene still had an effect on me. As well as being immensely haunting, it sparked my curiosity further.

There’s something mesmeric and certainly very magical about the instrument’s drones, and the motion and physicality of playing it: the way it vibrates and almost heats up against your body; the notion of curling around it, cradling the instrument; hearing it, playing it, has a very emotional and transportive effect. There’s a rich, majestic, and ancient, quite pagan quality in the sound. After many years working with synthesisers, having the immediate and very physical experience of playing such an intuitive acoustic instrument was a revelation. Bringing that more intensely into Cyclobe’s sound has been very interesting for us. Cliff Stapleton’s been a great inspiration with this of course, a marvellous guide with the instrument; I loved his recordings with Nigel Eaton.

Stephen Thrower: It is a versatile instrument, there’s such a wide variety of sound you can draw from it. There’s the characteristic dense drone with the melody overlay, there’s a fine, keening high tone for solo melody lines, and then there are all sorts of opportunities for ‘extended playing’, distorting or distressing the sound. Many times I’ll be working in my office downstairs at home and hear the most extraordinary noises emanating from our studio upstairs, and often it turns out to be Ossian coaxing some new sounds from the instrument. It also lends itself very well to processing, because you have the option of both harmonically dense sounds and pure tones.

Sulphur-Tarot-Garden (2014) – Cyclobe’s recent soundtrack to three of Derek Jarman’s short films

Derek Jarman, photograph by Ray Dean

TAROT by Derek Jarman

OB: We chose the films together with James Mackay, Derek’s producer and close friend for many years. I was always very drawn to Derek’s Super-8 films, much more so than his longer films, and it was always an ambition to be able to make music to accompany them. Of course we dearly wish we could’ve shared the music with Derek whilst he was alive.

ST: Many of Derek’s short films have yet to be released commercially, so for a lot of people they’re impossible to see. I’m fortunate in that I knew Derek and I was able to watch them with him, back in the 1980s. As we made plans for our Meltdown gig at the QEH the idea came up to work with films as part of the event. It just so happened that James was in the process of creating high definition masters for the Super-8s, so the stars aligned perfectly. We watched quite a few and chose the ones which we felt had a quality that chimed with our musical style. Watching them I was struck by Derek’s love of arcane ceremony, timelessness, and the depth of detail and mystery you get with superimposition, and of course with Super-8 it’s very much about the texture as well, all of which maps onto our approach very well.

Derek himself used to put records on when he played you the films; there was no fixed soundtrack. Too much synch for films of this nature would be grotesque as they’re more impressionistic; in Sulphur, for instance, allowing two pieces of film to pass through the projector on top of one another involves a deliberate refusal of second by second decision-making; you allow the material to generate its own internal drama, having set the spools in motion. The process results in chance combinations of texture and image, so to attempt mimesis with the music would feel too contrived. It becomes a matter of playing with chance, you allow it to enter the recordings but you don’t let go of a vision for the outcome. On Tarot we took a different approach; we identified the mood we felt the most strongly, and summoned it with as much clarity as we could muster. Garden Of Luxor is structured more like sleep, shallow sleep to REM, a gentle slope leading to an abyss as you enter a fully realised dream world.

Wounded Galaxies Tap At The Window (2011)

Cyclobe – Wounded Galaxies Tap at the Window from Phantomcode on Vimeo.

OB: Some of the instruments on Wounded Galaxies… are presented in their pure state, as opposed to the more invasive synthesis on The Visitors for instance. Still there’s a great deal of adaptation on the album, mingling and fusing numerous elements together, melting them into one another. It wasn’t a deliberate move to change our sound; we just worked with what we felt each piece demanded. But as always, whether we’re working with heavily synthesised or purely acoustic sounds, we want them to transcend their source, to liberate them from the feeling of having been ‘performed’, to feel that they are born to your ears, alive and independent. I wish I could bury a piece in the garden after recording it, in the foot of a hill: feed it to the worms, let spiders lay their eggs in it, have it devoured by slugs or impregnated with fungal spores, covered in lichens! Then dig it up and listen to what it sounds like!

ST: I’ve always felt drawn to trying new instruments – the excitement of having a new tonality and texture to play with. I remember listening to the first Lemon Kittens album in my late teens and thinking wow, they start each track from first principles, the instrumental line-up and musical approach is different on virtually every track. I loved that, and could never understand how bands could tie themselves to guitar, bass and drums. We bought a big old xylophone and really fell in love with the richness of it, which made a big impact on ‘The Woods Are Alive With the Smell of His Coming’.

OB: There are narratives that run through the album, very much so, and some of the titles have personal significance for us. You could look at them as words to ‘change your state of mind’, to alter the atmosphere before you enter a new environment. They’re emotional triggers, opening channels. I’d feel reluctant to cement our personal narratives on the work too firmly though, on something that’s for the listener is very fluid and free. These pieces are mostly wordless, but not without intent.

ST: Listeners quite naturally have questions about what they hear, and titles are just about the only lingual element in our work. We don’t use lyrics, and if there are voices in the sound they are non-verbal or indecipherable. As such the titles are the only linguistically comprehensible utterances we make! This then puts a lot of weight on them, because, for better or worse, our culture is heavily word dominated. A fifteen minute instrumental in which a voice spoke a single word would immediately be seen as a statement and the music would take a back seat to the meaning imputed to that word. The associations that accrue to the titles, we feel, should remain in the control of the listener, to go further would be to turn the listener’s journey into a problem-solving exercise – how to make the sounds tie in with the band’s preferred narrative. ‘How Acla Disappeared from Earth’, being the first track, sets a journey in motion, and ‘Wounded Galaxies Tap at the Window’ compresses the cosmic and the intimate into one image, but beyond that the connections and echoes and ideas that spring up between them is sacrosanct to the listener.

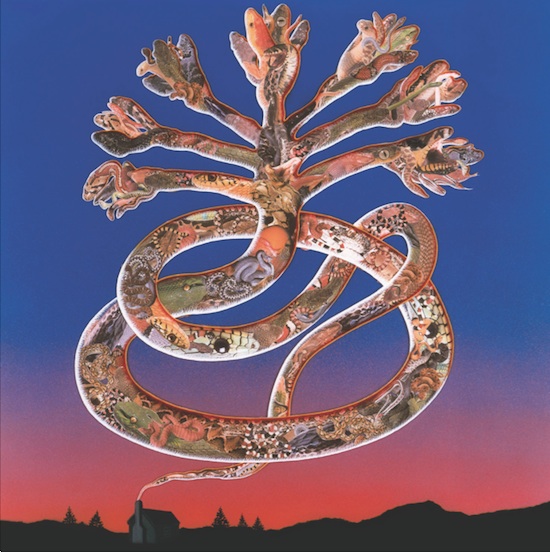

Fred Tomaselli (US-based visual artist whose painting appears on the cover of Cyclobe’s Wounded Galaxies… )

Wounded Galaxies artwork by Fred Tomaselli

OB: I first came across Fred Tomaselli’s work at his White Cube exhibition back in 2001. I went to it with Jhonn Balance and we both became great admirers. Ectoplasmic Event Over New Jerusalem is phenomenal. Fred’s Fungi And Flowers, Expecting To Fly and Doppleganger Effect, a picture we’ve worked with now in Cyclobe… these are enormous, transcendental works, full of great beauty and absolutely engulfing, you can almost feel your molecules begin to dissolve into them. They’re an absolute vortex. I feel that in Cyclobe we explore very similar terrain. Before we’d even begun to piece together the components that would become Wounded Galaxies…, his picture Generator was there informing us. I knew, back in 2001, that I must make contact with Fred, so to connect with him was just great.

ST: I see a similarity between our approach and Fred’s. There’s an obsessiveness and a love of detailed texture in his work that I feel an affinity with. He has an interest in many altered states of consciousness but in a beautifully elaborate and organic way – there’s nothing cheesy about his psychedelia! Something I hope is true of our work too. My chemical explorations are in the past now, but it left a deep impression in my thinking; there are contours and pathways embedded in my brain that will never diminish, and doors that flew open long ago. These things affect me when I’m working on music today, even though the strongest mind-altering substance in my life is Bolivian coffee.

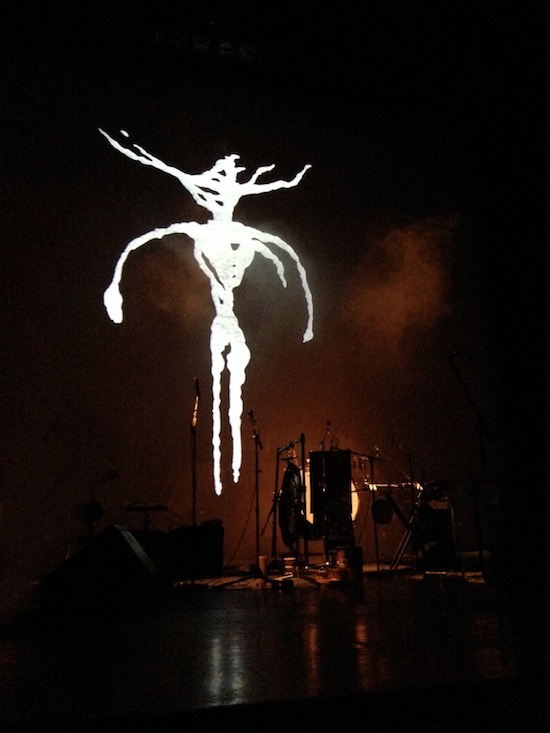

Cyclobe, Queen Elizabeth Hall, London, 4th August 2012

Cyclobe live at QEH by Olivier Naudin

OB: In many ways the QEH performance felt as though it were our ‘first’ concert, in terms of it being close to what I hoped it should be. Six years prior to that, when we played in Krems, we were really just testing the ground, and although it went well I came away feeling very distressed and frayed by the experience. On reflection I don’t feel we went deep enough. Afterwards I just wanted to vanish and return to recording, I had no desire to perform live again. I feel now that the stars weren’t in their correct alignment for us to realise the kind of sounds and atmospheres that were essential to re-imagining our work in this way. To generate the feelings of transcendence we wanted. It was all very different after we released Wounded Galaxies…; after those recordings we felt much closer to many of the people we’d been working with. The QEH event was very important for us. Personally, at that stage, I wouldn’t have agreed to do it for anyone else other than Antony. It was a gargantuan step for me, but I can see now it was the right time.

ST: Preparing for our show is difficult as our band members are pretty spread out, geographically, and it requires a lot of effort to pull us all together. The experience of performing the music live makes it worthwhile though. I’ve played live many times with my improvisation cohorts in The Amal Gamal Ensemble, and with Dave Knight in UnicaZürn, so my stage-fright is fairly manageable. Once all the technical challenges have been overcome the actual performances are very satisfying and fulfilling, not least because people have responded so positively; I suppose I might feel different if we were booed off!

Paraparaparallelogrammatica (Cyclobe’s 2003 release, based on source material by Nurse With Wound)

Paraparaparallelogrammatica artwork by Babs Santini

OB: When Steve Stapleton initially sent us the recordings, having asked us if we’d like to work on them, at that point we really weren’t sure whether we should. We’re not really very keen on the ‘remix’ idea. In a few instances it can be interesting but … we’d really rather concentrate on new recordings without those kinds of restrictions. When we first heard Steve’s LP it was already sounding incredible. Why on earth would we want to alter it? Anything we might add would feel superfluous, just minor decorations to something that already sounded quite unique and accomplished. It was hard to know how to approach the idea, so we decided the only way to work with his material was to be incredibly invasive, using it really as a spring board to take us somewhere quite different and to feel completely free. The ambition was to create something with only faint shadows or ghostly outlines of what it once was, with the original raw material occasionally revealing itself, as if by palimpsest. Steve seemed very happy and incredibly open to that approach.

ST: It’s a pretty full-on record… I felt very energised making it because hearing NWW for the first time in 1982 transformed my understanding of music. I just couldn’t get enough of those first six or seven albums, they brought such a torrent of new ideas into my head. I really admired his approach and it freed up my attitude to other music too. For instance, I’d been listening to Stockhausen at the time, which I was struggling with initially, but when I heard the Nurse albums a kind of synaptic flash happened; I could hear Stockhausen better after hearing NWW, I could really feel the adventurousness of it, whereas before I’d been tripped up by the anxiety that there was probably some grand design that I wasn’t getting. I found my own way to relate to Stockhausen through NWW, tapping into the mad vitality and cosmic energy of his music. It was really the beginning of my attraction towards abstract sound collage and music without a repetitive or dominant rhythmic element, leading ultimately to the electro-acoustic masters, Bernard Parmegiani, François Bayle, Guy Riebel, and maverick sound artists like Tod Dockstader.

The Visitors (2001, re-released 2014)

The Visitors cover artwork by Alex Rose

OB: Time feels so dishonest, to me it feels about six years since we first released The Visitors, or even less! At the time, aside from the obvious connections with our other projects, the music we were making felt out on a limb … we felt quite isolated. I don’t think it’s ever sat comfortably within a particular genre, that’s never been an aim of ours. We have always hoped to make a music that operated ‘out of time’ and perhaps because we’ve never been particularly ‘technology’ driven, and with our interest in such a wide variety of instruments dating from many periods, our music in turn has perhaps become harder to date, its location in history more slippery.

ST: For me the initial impetus for re-releasing The Visitors was a desire for our older records to come out on vinyl, as they were never released in that format at the time. Thirteen years sounds like a long time in a band’s career, but the record still has a lot of freshness and vitality to it, and I’m proud to say I don’t think it sounds dated. We’ve always instinctively avoided using certain kinds of sounds, beats or cultural markers, which might fix a sound to a particular time. I guess my feeling is that there’s a strata of music that hasn’t dated because the implications and possibilities have not been exhausted, and also they’ve not been taken up by ‘trend-setters’ from outside, which would tend to date things.

Perception of time seems affected by the amount of time you’ve been self-aware, so when you’re twenty you’ve only been conscious of yourself for maybe ten or twelve years; a year seems such a long time in that context, a tenth of your conscious life! If somebody says "let’s do that next year," it sounds like a brush-off, just nonsense. By the time you’re forty or fifty a year seems to flash by in no time, and saying to someone "let’s do it next year" feels as sane and simple as "see you next week"! So you don’t quite comprehend, as you’re living it, how time changes in your head. Until one day you look back and see that an album that still feels quite recent to you was actually made over a decade ago…

OB: ‘Son of Sons of Light’ [a newly recorded track for the re-released version of The Visitors] came from our working more intensively with Michael J. York whilst preparing for our first London concert. We always felt that the final section of ‘Sentinels’ [the album’s opening track] never really ended [and] developed very naturally into ‘Son of Sons of Light’…. It is has an aeonic quality, it just recedes temporarily into the aether. For it to re-manifest now as ‘Son of Sons of Light’ feels entirely appropriate. We wanted to share something of the present with the release of The Visitors, a feeling of continuation and of folding time, but without interfering with the album as it was initially intended to be.

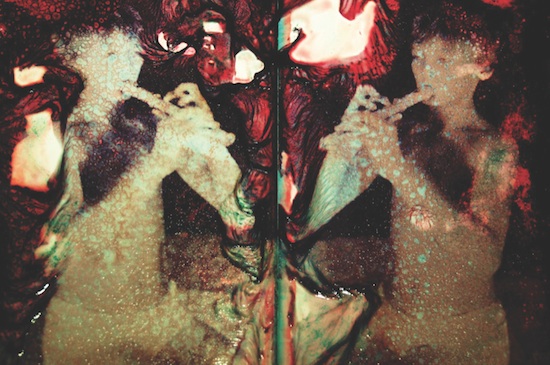

Alex Rose (Irish visual artist whose work adorns all of Cyclobe’s releases to date)

Artwork by Alex Rose

OB: Alex’s work for The Visitors is astounding, and so beautiful – a phantasmagorical picture, with a feeling of great cosmic majesty, but laced with a feeling of melancholia also. For me it conjures visually, in concentrate, the essence of those recordings. It has me recalling Strindberg’s celestiographs, his experimental photographs from the 1890s. This great body of stars, birthing galaxies. It works so intensely and magically for me with Fred Tomaselli’s Black Acid. I find Fred’s piece riddled with hallucinatory cyphers, it has a very compelling and magical effect. Before, I could have only dreamed of something so appropriate. For me the picture is utterly alive, a captured moment of something eternal and shifting. I find it incredibly moving. Alex reached out to us, initially, and very quickly we became close friends.

ST: I love Alex’s pictures, they have such a rich and varied texture and there’s so much detail and mystery and clashing registers of feeling in them. They’re bursting with information and ambiguity. Sometimes there’s a sort of sickness in them, like something distressing seen in a fever, sometimes it’s cosmic and open and flying away. He’s so good with texture, there’s a complex array of mutation and decay in the emulsion. I think there are similarities in his working method to our approach with sound, there’s a fascination with change, mutability, organic processes and rendition to primal ooze. Whatever The Visitors may be, one thing it isn’t is clean! People often tell me our sound oozes into their ears, and I think that tactile sensuousness, on the threshold between arousing and distressing, is there in Alex’s work too.

Luminous Darkness (Cyclobe’s first album, released in 1999)

Cyclobe Luminous Darkness – Artwork by Ossian Brown

OB: It was an incredibly insular time for us, recording Luminous Darkness. It was the beginning, so we really wanted to keep other people’s involvement to an absolute minimum, we were very much focussed on each other and learning this new way to communicate and be together. We were still very curious about what might come of it, and it wasn’t a given that we’d be able to find a shared language. We had so much we wanted to communicate with that album, maybe too much. We wanted to achieve something of what Arthur Machen said when he wrote, "to the ear what slime is to the touch"! An ectoplasmic sound. We were very excited by the techniques used by electro-acoustic artists, the way they manipulated and mutated raw sound, to make it move and envelop you, how they played with perspective and distance. But for me personally, a lot of it lacked strong emotional content or spiritual depth. It could feel quite gratuitous; a marvellous demonstration with astonishing sounds but they didn’t move me, and I always want music to move me.

ST: The electro-acoustic approach was very important to our early recordings and I love the freedom of that pure abstraction, whether cold and detached or rich and emotionally resonant. It’s true that Luminous Darkness is much harder, it’s a lot more angular. There is harshness there but it comes from the sheer blast of energy we felt working together. Emotionally I was in a darker place in the late 1990s, some heavy personal problems, the tail-end of my drug use, so that fed into the music as well. The shorter pieces are examples of the excitement we felt at having begun working; there was an explosion of ideas and a desire to get as many of them down on record as possible. Some of it is quite primitive, inasmuch as we still had a lot to learn about studio technique. Other tracks sound like pointers towards our later sound (‘You’re Not Alone, You’re Dreaming’ for instance) or would develop into more elaborate and monstrous forms on Paraparaparallelogrammatica, so for me it doesn’t feel completely disconnected from the other records. I still like a lot of it and we will certainly re-release the album as we did with …Visitors.

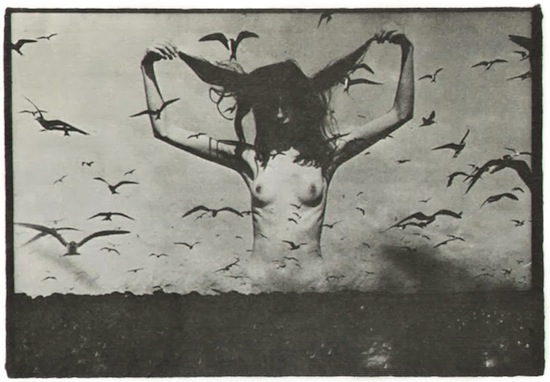

David Larcher

By David Larcher

ST: I first became aware of David’s work thanks to a screening of his Video/Void on late night Channel 4 back in 1994. It’s an incredible piece that uses video drop-out, tape damage, signal glitches and colour burn-out to create amazing abstract forms that take on the appearance of landscapes, gradually mixed with film material until you can’t discern the difference between digital abstraction and the representational image. I met David 10 years ago, after a screening of his film Mare’s Tail at Tate Modern. We got on well so I sent him copies of our albums and went to visit him. He showed me some extracts from work in progress, all of it fascinating. I think there are some striking similarities between the way he works with images and the way we work with sound. We are fascinated by the grain of sound, the texture and associational richness of it, and we play with it in an obsessional way that I can see in David’s deeply layered and textured visual approach. He grabs a hold of technology and pushes at its boundaries to create intensely lysergic visions, and that’s not unlike our approach to music. His work has an intellectual dimension (and a prominent linguistic element) but it’s far from arid: Mare’s Tail, parts of which we’re privileged to be able to use in our live show, takes the viewer on a cosmic journey from nothingness through birth and on to death. There’s a wonderfully free and dauntless attitude in his work which I find very inspiring.

‘The Woods Are Alive With The Smell Of His Coming’

ST: Blood, sweat and tears went into that one! The challenge was dreaming up something with a rhythmic drive that nevertheless stays just as receptive to deviation and digression as any of our more ‘electro-acoustic’ pieces. The rhythm became a forest trail around which all sorts of visions and voices could press themselves, sometimes so tightly that you feel you’re being swallowed. Narratively, it’s the most detailed and ‘storylike’ piece we’ve done, to my mind its antecedents are progressive rock pieces like ‘Close To The Edge’ by Yes, or Van Der Graaf Generator’s ‘A Plague of Lighthouse Keepers’. Structurally it came into being after we did something quite nuts and pressed two very complex multi-track pieces into one. We ended up with something like an eighty-track master, but from that deep dark tangle we managed to find a form that sustained us through the whole eighteen minutes. It’s one of the pieces I’m most proud of, first of all artistically with the result, and also in the commitment to finishing it despite wanting to scream and jump out of the window many times!

OB: You could say that it is concerned with the manifestation of nature that you can’t suppress; a nature inside as well as outside, PAN as the instinctual soul. Being lost in the intoxication of wild and dark woods. It was completed to coincide with the exhibition The Dark Monarch (Magic and Modernity in Modern Art) at the Tate St Ives. We’d been working on the piece for at least four years, in a fragmented way, but The Dark Monarch really spurred us on to complete it and gave us the energy to finish. When I think of fantastic English artists like Graham Sutherland with his wild and abstract nightmare landscapes, or Paul Nash, or Samuel Palmer’s Shepherds Under A Full Moon or The Lonely Tower which was shown at the …Magic And Modernity… exhibition, the connection feels very strong and inspiring. It was gratifying to have our work played in that company. I wonder what England must have been like before the Enclosure Acts in the 1800s, before landowners were allowed to fence off the fields, to enclose the wild woodland, the common land and wastelands, changing our ancient landscape forever. Suddenly you have a countryside composed of giant square fields and man-made borders, severing us physically and psychically from nature. We became trespassers. Nature is there, around us, but how can you really freely step into it? Our relationship to the countryside and nature I think changed radically because of this. There’s a wonderful quote from Jean-Jacques Rousseau: "You are undone if you once forget that the fruits of the earth belong to us all, and the earth itself to nobody."

Cyclobe perform at the Unsound Festival, on 18 October 2014, more information here. The vinyl re-releases of The Visitors and Sulphur-Tarot-Garden are available from Cyclobe.com