Photos by Sidd Khajuria

The curtain rises, and from Row M in the Barbican Theatre it’s hard to tell which of the figures is the inimitable Welshman. Faded are the pink highlights that until recently dominated his shock of white hair; present is a slight pot-belly that becomes visible in the backstage interview that takes place an hour after the show. Co-responsible for some of the landmarks of post-war Western culture, John Cale refuses to amble peacefully into the "elder statesman" fold, these days preferring to experiment boldly and preach the perfection of Snoop and Pharrell’s ‘Drop It Like It’s Hot’, which he holds as equal to anything Brian Wilson did in the 1960s. On stage now, Cale suddenly stops fiddling with his guitar and strolls over to the keyboard, behind which he executes small, discordant, multi-note fillips until his vocals begin.

This is no ordinary concert, even by Cale’s standards. In collaboration with "speculative architect" Liam Young and a group of dedicated and talented technicians and artists, he’s attempting to radically recontextualise his music, aesthetically and conceptually. His main method for doing this is by pioneering the use of drones in music. "But he’s always done that!" you cry. Well, here, rather than simply letting notes and themes drift on ad infinitum, he’s using actual mechanical aerial drones. Drones that hover beautifully, romantically and sometimes ominously above the audience as the latter gives up trying to track both music and visuals, and surrenders itself to atmosphere.

Cale only discovered Young under a year ago; the pair and their team have worked fast. He was first exposed to Young’s work through his website, Tomorrow Starts Today. "There were a couple of things on there that were really extraordinary," enthuses Cale after the concert. "One was this piece in Holland where he put some drones in the air that flew over the rooftops into a central square, and established a WiFi signal. And I thought that was really subversive. So good."

I ask Cale how he thinks the concert went. "I couldn’t tell," he says honestly. "If you’re doing something new, you can’t always depend on being able to see whatever it is that’s going on, or understand the audience’s point of view. I just look for the core strengths of the piece." He repeatedly refers to this notion of "core strengths", whose only objective characteristic is, ironically, that they are totally subjective. "The core strengths really allow you a lot of freedom. Because you’re feeding morsels of imagination to [the audience]. You’re giving them vehicles for their imagination and it’s endless. You can do anything you want in that context. And as long as everybody is happy to [partake in this], they can contextualise it themselves. It’s a great canvas to work on." With this bent towards subjectivity, you could argue that he’s come a long way from the blunt, unequivocal Cale that gave us that gem of an opening nearly forty years ago: "The bugger in the short sleeves fucked my wife".

Then again, suggestibility has often been inherent in his music. Tonight’s set-list is full of reinterpretations of his work, revealing an almost childlike openness to his lyricism. Lines like "Mustn’t be late for the caravan/Mustn’t be late for the garbage van" can pretty much be delivered any which way. Most of tonight’s set is deadpanned; one exception is the opener, ‘Mercenaries (Ready For War)’, whose lyrics are rendered incomprehensible by the throatiness of his warbling vocals. The falsetto delivery is a refreshing change from the original, and the ‘Looking for work’ refrain seems like a deliberate irony considering Cale is one of the most industrious studio musicians of his generation.

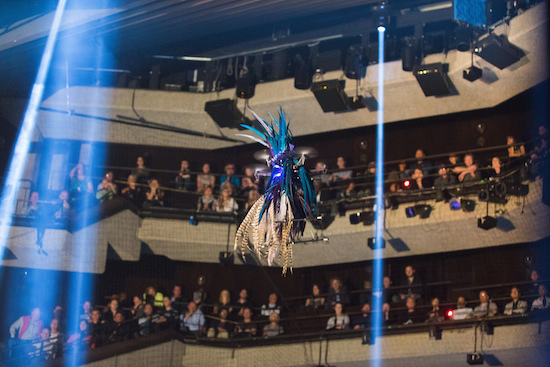

Like his old friend Brian Eno (whom he hasn’t seen for many years – "We’re into different things at present"), he’s consistently innovative. More on the flying drones: we see the first one before the music begins proper, rising slowly, majestically – a thing of globular beauty, a nexus of tubes and tentacles. It’s unhuman rather than inhuman, and, accompanied by the droning instruments and the eerie blue light, brings to mind the final set-piece of Spielberg’s Close Encounters. It twirls happily through an invisible gridded catwalk before descending to be replaced by two decidedly less opulent drones that hover about aimlessly. Naturally, health and safety requirements inhibit any real physical interaction with the audience: the drones dance jerkily high overhead, fanning luckier audience members with the gusts of air generated by their levitation. The creatures’ function seems at first to be primarily visual; but after the second track, one humming drone rises like a mesmerising mosquito, showering onlookers with glittery confetti.

Cale has, in the past, been famed for his audience interaction, which has been known to involve violence towards poultry. Tonight not a single word is spoken. Presumably, this is a function of the new "core strengths" of his music and its new visual component; indeed, the effect is hypnotic. This is due in no small part to the Dan Terry-designed lighting, which is phenomenal. Later I ask Cale about the lighting. "It takes a bit of work to shake off the rock-show blues, when everything’s flashing all the time," he says. "What I was trying to get [the lighting] to do was to mesmerise people. That’s what [lights] do, and what my music does as well, to a certain degree."

I tell him that the lighting reminds me of one of the installations at the Barbican’s Digital Revolution exhibition, specifically one "zero-player game" comprising two random path algorithms running along a fine grid. One algorithm, as it randomly travels across the grid, causes the small squares to light up, while the other one goes on deleting lit-up squares. Endlessly fascinating, mutually destructive patterns emerge, and within those patterns, sub-patterns can be discerned. "It’s all allegory," opines Cale, though he doesn’t get much more specific, quietly sticking to his "subjectivity of art" line. ‘It all represents something or other. People will attach emotions to movement, to proximity, to just the way things look.’ He expands on it by talking about how the drones in his concert were set up. "The [team] built a virtual grid, so that whatever pathway the character drones went, they wouldn’t fly into a wall. Up until the afternoon of the last day, they were still crashing. And that poses all sorts of problems. I mean, there’s nothing you can do about it, but it’s like, ‘Oh dear. There’s this dead [drone] body right there.’ And you have to stare at this dead body."

The concert is now approaching maximum quirk. "I’d shake you by the knees/Blow hot air in both your ears/If you were still around," mourns Cale, while his arms swing loosely, hands lolloping trancelike from knee to knee. The drones continue to soar, trying to lend hope and optimism to the music; one drone in particular, with the blue hair of a ’70s punk and the lower half of a cuttlefish, is beautifully rendered. Meanwhile, the vertical shafts of light hang iridescent in the air. As ‘December Rains’ crawls into earshot, the light show steps up another notch: diagonal blue beams of light vanish quickly and slowly reappear, like a luminous photon forest. The beams seem to be enjoying their Heisenbergian intangibility: you think you’ve located a beam, when it disappears from view, only to slowly reappear while you rub your eyes, befuddled. Cale’s lyrics, meanwhile, want to be grasped: "I’m not afraid now of the dark anymore. People always bored me anyway." The drones, naïve, like electronic enfants sauvages, carry on.

Cale claims that the drones were more-or-less autonomous, but the booklet to accompany the concert lists several "pilots" – and indeed, there do seem to be some people underneath the stage, visible to the audience, staring so intently at the aerial beasts that they seemed telekinetic. Mystical though it seemed, one would assume they were flying the drones by hand-held remote control.

The musician is particularly animated when talking about jazz. "There was this one concert I went to in Munich. I was playing at a festival there. And the day before I was due to play, they had Ornette [Coleman], and the Moroccan drummers, together. And the drummers, in their fezzes, with this gong and these big drums – what a noise! It was tremendous. And then Ornette comes on, in a gold lamé suit. And he takes the microphone, sticks it in the barrel of his baritone, and then just blasts. And I mean, he is loud. I mean, I knew about mixed media, and about cross-cultural blends, but I thought: there’s not much thought at all going into this." He continues somewhat confusingly: "There are abstractions that don’t come from personalities, but come from a system. The abstraction you’ve got [with Ornette] is the abstraction of a system."

It’s hard to tell exactly what he’s getting at here, but profess my profound love for Miles Davis’ angry electric ’70s output, and draw a parallel with Cale in that Cale plays his viola with his back to the audience. It turns out that he plays like this for the same simple reason that Miles did. "You go where you can hear. And with all the stuff that’s around, like drones with speakers, you strain to hear what you’re doing – you don’t want to be that loud, because you don’t want to orient people near the front of the stage. You want to be in this sort of bowl." Occam strikes again: it may look cool to pay no heed to the audience, but the practical reasons for this outweigh the aesthetic ones. The aesthetic ones are more fun; but hey, I guess that’s rock & roll mythology.

"Take me with you, take me away," sings Cale on stage, partway through Black Acetate’s ‘Gravel Drive’. He’s moved from keyboard to viola, and is facing away from a large drone whose top half is shaped like the head of an Architeuthis. It dawns on me that tonight’s concert is far more beautiful, compelling, and strange than it is galvanising; sometimes the arrangements don’t quite work. ‘Letter From Abroad’ is transformed from a powerful, chaotic mini-masterpiece into a portentous dirge whose refrain sounds like the work of a sardonic Adrian Mole. Naturally though, he makes lines about hyenas and lions come alive. I wonder if he knew that female hyenas give birth through their clitoris. Then I realise that if he did, he’d have used it in song by now.

It’s hard not to love Cale’s Welsh Sprechgesang, and Cale seems fairly proud of the Welsh aspect of his identity; ‘Child’s Christmas In Wales’ is one of his most famous songs, and he called his autobiography ‘What’s Welsh for Zen?’. I ask why he never actually sings in a Welsh accent. "I’ve lost track of my accent," he replies. "I mean, in ’63 I arrived in New York… about two years later, my friends told me that for a long time, there was a lot of smiling and nodding going on because nobody understood what I was saying…. It was a strange position to be in. I would go back to Wales to visit my parents, and I’d get treated like a snob."

Why does he spend most of his time in L.A.? "It’s kind of in my bones. I can go to the gym very regularly, I can go swimming. I can keep myself in better shape, and make sure I eat properly. I’m not a vegetarian," he admits, "But I’m close." It is at this point that I notice his pot-belly. I want to tell him that none of these reasons are reasons to prize Los Angeles above just about any developed city in the entire world, but I decide against it. To be honest, I’m not sure he’s being serious. You never can tell with this gnarled, gnomic enigma. His list of things that disturb him include ‘kids and choirs’, ‘predatory behaviour’, ‘ignorance’ – and ‘happiness’.

He talks openly about rehearsing ‘If You Were Still Around’, synchronising the drones’ behaviour with the music. "You suddenly saw these two drones wandering around the room. And bingo – there was this relationship that was created. And I hadn’t created this relationship; or maybe I did, unconsciously… but you listen to the song, and then you see this – and all of a sudden, it’s illustrative. I didn’t want to do that; as soon as you want to do something, you get stuck. And you have to follow through with a plot. That’s not really what I saw this as being about. This was much more generous to the thought-processes of individuals than just my pinning it with this, that and the other."

These are the "core strengths" to which he keeps referring – every performance is different. "Which I love! I mean, I hate doing the same nonsense, performing the same songs." It’s clear what he means, although tonight’s setlist is the same as last night’s. The concept he’s unleashed at the Barbican is invigorating, inspiring, and new.

The concert technically ends with an encore, ‘Strange Times In Casablanca’; but really, it ends with a surprise rendition of ‘Sister Ray’, which no-one was really expecting. At first it’s impossible to recognise, but a repeated one-note keyboard riff and the band’s vehement aural attack give us an idea. Any doubt is dispelled when the words ‘Duck And Sally Inside’ – as momentous an opening as ‘Stately, plump Buck Mulligan came from the stairhead’ – leave Cale’s lips, to a roar of approval from the audience. This new version bears more resemblance to Joy Division’s famed April 1980 live version than to the Velvets’ original, though Cale appears to be mimicking Lou Reed’s style of delivery.

Whether this is conscious or not is unclear. What is clear is that in interviews of late, Cale does not seem too forthcoming about the late Lou. I ask him about Songs For Drella: whether he listens to it often, or thinks about the sessions. "Too much baggage," he mutters. "I avoid it. It was sort of a depressing idea. I mean, Andy’s not around, there are a whole bunch of people who aren’t around. And I don’t want to think about that." He laughs somewhat ominously when I ask him if he ever listens to any of Lou’s solo albums, and I take this as a cue to move on hastily. I ask him about the recent re-release of Le Bataclan, Paris, Jan 29 ’72, his live album with Lou Reed and Nico, but this is the first he’s heard of it. "I had no idea," he professes. "I don’t follow that stuff. I know it’s been shifted and shunted all over the place; the ownership was never clear. So what everybody did was try to take copies and spruce them up. They all sounded like shit." One thing he does remember: "Nico dominated the stage. Her timing was uncanny–"

Speaking of uncanny timing, we’re interrupted by his agent, and the conversation thread ends there. Needing to wrap things up, I ask him if any of his ’60s and ’70s contemporaries continue to surprise, excite and please him musically. "Beck keeps producing a lot of good stuff," he says briefly. Cale loves Beck. I remind him that he [Cale] has been responsible for writing and/or producing some of the most memorable opening lines in music history, such as the aforesaid one about the adulterous short-sleeved bugger, and the eternal ‘Jesus died for somebody’s sins, but not mine’, and I ask him what songs’ opening lines have most grabbed him. His three answers are Beck’s ‘Loser’, Curtis Mayfield’s ‘Pusherman’, and Leonard Cohen’s ‘Hallelujah’ – which Cale covered to memorable effect back in 1991.

But any Cale fan knows that he likes to keep up to date with new developments, and he wastes no time in plugging his latest find. "A little hip-hop group from southeast Georgia called Ca$h Out. They’re really interesting. I don’t know if there’s one guy or two guys singing, but one of the guys sounds like an old man. And it’s fascinating. They mix digital drums with analogue drums, and it’s beautiful. It was only a matter of time before somebody put that together."

The devil’s disco continues as halfway through ‘Sister Ray’ Cale takes to the viola, his sawing growing increasingly febrile. Four drones are in the air now, hovering menacingly; these are militaristic looking things, not the large, playful, luminous "character drones" of the previous songs. He soon returns to the keyboard, and begins to repeat the ‘ding-dong’ part with childlike, devilish brio. His delivery and intonation shift the theme from fellatio to straightforward trolling; he’s revelling in his role as the septuagenarian belting out "She’s busy sucking on my ding-dong", his voice still in fine, fiery fettle.

He laughs heartily when I tell him later that he "went a little crazy on the ding-dongs". He finally, and perhaps inadvertently, acknowledges an awareness of the power of his performance. "That was good," he relents. It certainly was.