Any collection of poems published in 2014, or the past seven years, give or take, with a title like You Can Make Anything Sad will have to contend with a desire amongst critics to instinctively lump it in with all the other Alt Lit being made that month. What Alt Lit is, however, is far less interesting than how it manifests itself in the culture and what it tells us about the writers who claim to be a part of it and those who don’t. If you’re not familiar with Alt Lit, I suggest you Google it and waste some time mired in some of the most futile and boring internet disputes imaginable.

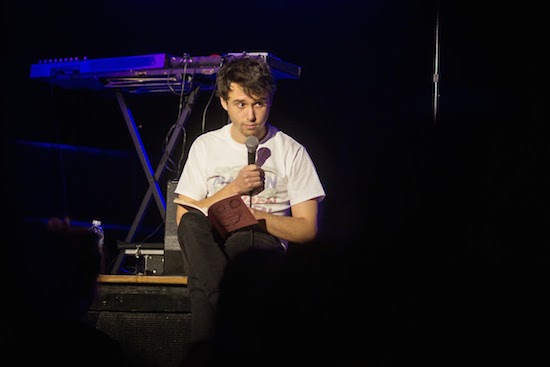

Spencer Madsen is a young Brooklyn-based poet who also runs his own press, Sorry House, while holding down a “proper” job at a bike shop. His first book of poems, A Million Bears, published by his own hand in 2011, was something of an internet sensation, one excerpt accumulating over 100,000 notes on tumblr alone, fuelling a surge in requests for the book which Sorry House struggled to satisfy. His most recent book – the aforementioned You Can Make Anything Sad – came out in April via Publishing Genius, based in Baltimore.

Just where Madsen’s work fits in, in relation to the Alt Lit milieu is reasonably easy to figure out: Sorry House publishes <a href=” http://thequietus.com/articles/13277-two-poems-mira-gonzalez” target=”new”>Mira Gonzalez, an interesting poet working in and outside of what is commonly considered Alt Lit. Among other notable writers, Madsen is friends with Tao Lin, <a href=” http://www.thefader.com/2014/03/07/interview-spencer-madsen-writes-real-life-poetry-for-real-life-attention-spans/ “ target=”new”>telling The Fader, back in March, “I feel like a part of a friend group that borders on family, and could be called a community.” Where Madsen’s work fits in, in relation to poetry, generally, is a more interesting line of inquiry. But Vice’s quoted description, at least, of Alt Lit as “a kind of pointedly botched poetry whose writers cultivate bad spelling, weird punctuation, sincere statements of the obvious and a spontaneous expressivity evocative of erratic pubescent passions” doesn’t seem to correlate with what Madsen is offering.

You Can Make Anything Sad opens with a bravura appeal to connect with the reader, an at once humorous and seemingly-sincere attempt to welcome you into the world Madsen’s presents on the page:

Whenever I have an uncomfortable interaction with someone I want to say, “Look I’m a lot like you. We have a lot in common. We’re both going to die.”

Then poke them in the stomach to make them giggle.

It’s a strange tone for an Alt Lit title to announce at its outset. It suggests that Madsen is not con-tent to singularly operate in the accepted register of irony, detachment, boredom.

The principle grounds upon which Alt Lit attracts scorn are ancient ones: many people profess to have a problem with it based on its apparent narcissistic tendencies, its propensity for assuming the presence of profundity in every utterance. But, the major problem these readers have with Alt Lit, like all Minimalism, is the balls it takes to present seemingly next-to-nothing as art. The phrase, ‘my five year old could have done that’ is never far away from any Jackson Pollock, and the same is true, seemingly, for most works of Alt Lit. Of course, this doesn’t mean that Pollock and the Alt Lit crowd at large are the same, or that they necessarily warrant identical treatment.

One of the most interesting things about Alt Lit is how occasionally terrible even the best practitioners of the style can be: there are lines by Tao Lin, by Marie Calloway, by Crispin Best; lines by Mira Gonzalez and lines by Spencer Madsen, that are so artlessly constructed that one cannot believe they bore the effort of any kind of critical appraisal. But they did.

Madsen’s, You Can Make Anything Sad, makes frequent “mistakes”: lines such as, “A new new new new new something. /Never ever always once a person does a do and dies” are designed to illustrate the failure of language, but when contrasted with Madsen’s better lines, they only really show a failure of thought, a lack of care that is frustrating because Madsen frequently shows himself to be capable of better. The reader feels compelled to reach into the page and shake the poet free of the doubt he is experiencing.

The collection places itself on the Alt Lit side of the Romantic tradition, using the form of a blog-style diary in which observations bleed into emotional self-diagnosis, punctuated by the ultimate in Alt Lit calling cards — the non-sequitur-addled speculative list.

My second most ideal editor is a blind feral three-legged corgi.

Dick like gogurt

Alt Lit detractors consider this the type of writing to be executed by those writers who simply can-not do the “hard stuff”: these are the abstract painters who were never taught to “do” Realism. Who never learned technique. Yet, perhaps we should consider the work on its own merit. Is there ac-tually anything wrong with this? Is this necessarily a Bad Thing?

Madsen and some of the Alt Lit writers are still showing us interesting things, but peppered amidst their work are multiple errors. Mistakes, oversights, apparent short-falls, that serve to make the work more human. More relatable. More accessible. This is a huge concern for Madsen, as he mentioned in an interview earlier this year, “When you get that moment when you have something interesting enough to say that you could ignore that text message, then you’re onto something that’s going to be interesting for the reader.” It almost lays the constructive process of this writing more open, Madsen doesn’t want you to have to work to get the work, he wants the work to grab you and draw you in, away from your phone. This work is unpolished, but not unambitious: the lines that land well indicate that Madsen has a talent, not unlike anything else, but a self-taught ear for a strong image.

My desk is more a place for my hair to fall and nails to yellow

than for my brain to think or hands to move. If you

look close enough at the wood-grain lacquer you will find

curly thin hairs that were once a part of me. Dying calmly in

fractions of a billion, my desk holy.

These lines land because of the mindset of a writer who is not afraid of failure where almost every writer is afraid of failure, but Madsen’s poetry seems to accept failure as a necessary component, a defining feature of its own identity. It’s a hard literary trick to pull off: glaring omissions in punctuation, inconstancies over line breaks and careless editing are the trademark of the amateur. Yet, Madsen sells his books for money.

Madsen is generally better at talking about other people than he is at talking about himself and his own work. I found this out first hand when I attempted to interview him for this piece. Asked whether he considered his poetry ‘romantic’, he responded, “Jesus.” If charm has any literary merit, Spencer Madsen has found it. The ‘Spencer Madsen’ narrator in You Can Make Anything Sad is a rare instance in literature of a depressed and alluring voice. Madsen presents himself as the poète audit, who can also make a joke about his cock’s similarity to a tube of yoghurt. Is humour a defence mechanism in his poetry? “Humor underscores sadness, sadness underscores humor. Have you read any other interview I’ve done?”

You Can Make Anything Sad seems to encapsulate everything Spencer Madsen wants to say about poetry. The collection itself seems to explain why he is so reluctant to talk about poetry, per se: Madsen isn’t concerned with the world of poetry in the slightest. He seems to consider the job of the poet as singularly defined from the job of the critic, whose prerogative it is to have an immediate sympathetic familiarity with wider world of poetry. You talk about it, I’ll do it, he seems to suggest.

I ask him anyway: who does he read? “Are we done?” Does he have any kind of reader in mind when he writes? “We’re done.”

You Can Make Anything Sad is out now, published by Publishing Genius