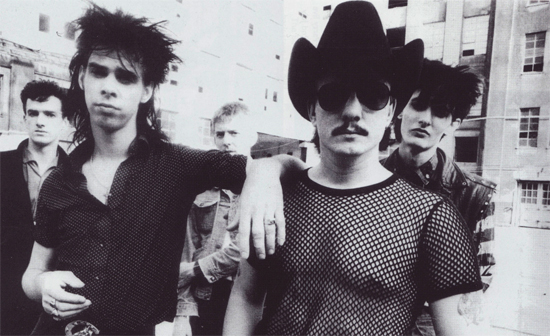

Birthday Party portrait by kind permission of Tom Sheehan

During their brief and often revelatory existence, The Birthday Party consisted of Nick Cave, Mick Harvey, Tracy Pew, Rowland S. Howard and Phill Calvert (until 1982). While only active for five years, only three of which were outside of their home of Melbourne, Australia, the impact the band had during that time was seismic. The most common expression when speaking to those who saw the group live, and even from those who were in the group themselves, is a deep, windy intake of breath as they relate – with a flurry of adjectives and nonpareil comparisons – their memories. Even Mick Harvey still can’t quite put his finger on the magic of the group today. "When we had a good night it was like nothing else. Like an experience, it went beyond the sum of what was happening," he recalls. "It seemed to have this ability to become this weird crossover cathartic art event or something… for a lot of people it was an important experience. Seeing the Birthday Party was a bit of a game changer."

One consistent memory among all I speak to who bore witness to the anarchic mania of The Birthday Party is of the unpredictable nature of their performances; a universal feeling, an atmosphere cloaked in a terrifying sense of the unknown. "It was on the edge all the time, there was a real nervous energy at the shows," says Harvey. "There was potential for anything to happen. Sometimes it felt like it was on the edge of some kind of violent explosion." Bad Seeds producer Flood recalls the "anarchy", continuing that "there was always an energy that was completely unpredictable, a bit like going to the circus – is the guy going to have his head bitten off by the lion? Or is the person going to fall from the high-wire?" Jim Thirlwell, aka Foetus, who would work briefly with Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds, tells me that "It would have the fervour of a Southern Baptist prayer meeting, it seemed very cathartic for all involved." This unpredictability created a situation in which the group seemed capable of imploding at almost any point. As a result, by the time they’d released their second and last album, Junkyard, they would be over as a band only a year later.

It may have been during the recording of Junkyard when the cracks began to appear. Squalid and miserable living conditions in their newly adopted home of England, which they loathed – "Rowland seemed to take London personally," Cave recalled in the 2011 Rowland S. Howard documentary Autoluminescent – alongside spiralling drug use and intra-band tensions contributed to the beginning of the end. To some this period was their peak, but it also charted their personal descent. Barry Adamson, of Magazine and later the Bad Seeds, played on a couple of tracks from Junkyard. He did so because bassist Tracy Pew was in jail in Australia for repeat drink driving offences. He recalls it as being "chaotic… lots of drugs, lot of madness".

One of the producers of the session and long-time Bad Seeds producer Nick Launey, who was brought in by 4AD because of his work on PiL’s Flowers Of Romance, remembers the sessions with brilliant detail. "My first experience working with someone on heroin was with Keith Levene. I couldn’t work out why he kept disappearing to the bathroom and sometimes didn’t come back, [and] when he did come back he’d either be inspired and prolific or very tired and just wanted to sleep … I first met them [The Birthday Party] when they turned up at the Townhouse Studio. I had managed to get cheap studio time in Studio Two, after midnight only, which suited them perfectly. They arrived with their gear at about eleven and I remember the receptionist calling me and saying ‘I think your band has arrived – at least, they look like one of your bands. Can you get them out of reception? They are scaring the other clients’. I think Queen were in the other studio. The daytime session in Studio Two was Phil Collins, who had finished and gone home by now. They walked in looking like they hadn’t slept in days, all smartly dressed in black like they had just come from church but maybe the church was a ruin with rats, and they hadn’t washed in weeks. Being Australian they were actually very polite, but impatient to start – a trait that Cave has never lost. The term goth did not exist at that time, certainly not in the way we would use it these days, but I will say that recording a song called ‘Release The Bats’ with people who looked like vampires was pretty fucking exciting!

"We recorded two songs, ‘Release The Bats’ and ‘Blast Off’, in one night. About halfway through I recognised the disappearing to the bathroom thing, but I’m glad to say it only added to the fuel and edginess of the night. There were some notable arguments that broke out; some were, I thought, unfairly aimed at Phill. My feeling was that he was the one that didn’t fit in, he was kind of nice, and I think not on drugs. Whatever was going on there was not to do with that night, it was a difference of opinion that had built up over time, and not for me to know.

"You may be surprised to hear that the other target of abuse was Nick," Launey remembers. "Mick and Rowland were definitely driving the session, they were the opinionated ones. I remember when Nick was out in the studio singing the vocal to ‘Blast Off’, they insisted that he redo the "Blaaaaaaaaaaaast off" bit in the middle section of the song many, many times. Poor Nick was completely out of breath and almost collapsing, giving it his all. Meanwhile Rowland and Mick were pissing themselves laughing, they said "get him to do it again, get him to do it again [laughs]"! After a while I made a decision that the first take was actually the best and played it to them with the best of a serious frown a twenty-year old can make. They came to their senses and agreed the joke was getting old, time to pick on Phill again!

"Generally I did feel that Mick and Rowland were kind of evil, but in a cool way. They were all very driven and had a strong sense of direction. At one point Rowland and Mick wanted their guitars to sound like a bee sting feels, so I EQ’d them with a huge amount of mid range – this wasn’t enough. So I put the guitars through two more graphic equalisers, cut out all the low end and boosted everything around 3K – which is the frequency that hurts. I did it sort of as an "I’ll show you’, because I was a bit pissed off at how they treated Nick doing vocals, [and] they loved it! So that became the whole approach to mixing – distort and make everything as abrasive and painful as possible."

The party line regarding Calvert’s departure after these sessions was that he was unable to play certain drum parts, although it was clear that personality clashes were just as great a catalyst. Howard would tell Offense Newsletter in 1983 that "Phill became increasingly unable to think of drumbeats as the songs became less predictable. So Mick and other people used to write the drumbeats and sometimes Phill couldn’t play them because he was far too conventional a rock drummer … He is a good drummer for that type of thing, but he just has very limited personal vision. There was a time in 1981 when he suggested that we should do a cover of a Beatles song. This was his contribution to the group, so obviously he had a very different idea of what the group was about."

As the Birthday Party became more popular their relationship to their audience had changed too, contributing further to their impending demise. The surprise component of the group’s feral attack was being replaced with a sense of expectancy. "The whole situation needed an audience and it needed an original response from the audience," says Harvey. "Crowds and groups of people by their very nature tend to start behaving like a mob, so that changed over time, especially once their was an expectation of how wild or exciting the show was going to be. When there was an element of surprise involved it worked best, when people would just come along and then be presented with this pretty wild show, not expecting it to be that confronting."

This would then go on to start shaping the new material and altering the way the group performed, as Harvey continues: "By 83 we were just starting to play slower and slower songs to kind of offset that expectation, because that wasn’t really what we were after. We didn’t just want people going nuts the second we started playing. We wanted them to be involved in what was going on properly instead of just having a pack response to it. We didn’t want an ordinary response."

The role of the audience had always played a pivotal role in igniting the onstage catherine wheel that was the Birthday Party. Chris Bohn, then the NME writer who wrote the group’s 1983 cover feature, and now editor of The Wire, says that "Cave had a really sardonic way of talking to the audience that created a tension and antagonism." This had seemingly reached the level of pure hatred by the band’s final days. "I don’t know of another group who are playing music that is attempting in some way to be innovative that draws a more moronic audience than The Birthday Party," said Cave in 1983. "This is not everybody of course, just people I see from stage, there’s always ten rows of the most cretinous sector of the community."

The group had discovered Berlin and felt briefly rejuvenated by it, finding it to be the antithesis of London. It was there that they’d spend some of their final days, recording their final releases: The Bad Seed and some of Mutiny! "I think the whole thing of going to Berlin did give us a little shot in the arm," Harvey recalls. New tensions between Cave and Howard were, however, starting to become more profoundly felt. "Nick and Rowland had started to disagree about writing credits, Rowland was obviously wanting to do other things and sing as well, so there were difficulties there. We were playing with that energy, the thing we had live. It was a very perilous existence, you needed everything else on the outside to be fairly normal because everything else was pretty chaotic, drug-taking and drinking and the way the live tours were, it was all pretty crazy… We were on tour and Nick was playing the guitar and writing these songs for what would become the Bad Seed EP, and I said, ‘Why don’t you write something with Rowland?’ and he said, ‘I’m not writing with Rowland any more’ and I thought, ‘Well, there you go. We’re in trouble now.’ If the two main writers in the band are not seeing eye-to-eye then it’s not going to end well."

The band’s final record Mutiny!, was half-recorded in Berlin and then finished in London. Tensions had now further escalated between Howard and Cave, with the latter not wanting to write songs with Howard at all, or to sing songs the latter had written individually. Chris Bohn spent some time interviewing them around this period. "Their ideas diverged a little bit and they could no longer be resolved as easily," he says. "Rowland wasn’t prepared to swallow that Nick wasn’t going to sing his songs."

The sessions were tense, tired and fraught. Mick Harvey recalls them as painful. "From an outside perspective it wouldn’t have looked like our creative juices had dried up, but I can assure you they had! Getting those five or six songs that ended up on Mutiny! out of the writers was really like getting blood out of a stone." While the end results sound far from a band drying up and rotting – if anything they sound as explosive, progressive and menacing as ever – you only have to watch Heiner Mühlenbrock’s short film (taken from a longer film that incorporated the Birthday Party in it, Die Stadt (The City)) to get a sense of the state of things. The film captures some of the Mutiny! Berlin sessions, primarily the recording of ‘Jennifer’s Veil’ and ‘Swampland’, and the black and white grain of the film adds to the overwhelming dank grey aura that the studio seems cloaked in. It’s not what is being said between band members that highlights clear difficulties, but what is not being said. Communication appears to have broken down and a strained silence plugs the gaps. Cave seems unwilling – and to an extent unable – to work with Rowland on nailing a take of ‘Jennifer’s Veil’, and a taut air of frustration is then added to the mix. The group are supposedly not fond of the end results, which is not entirely surprising given that it shows Cave nodding off from heroin use and struggling to complete takes.

Mühlenbrock’s twenty-five minute film (which ended up entitled Mutiny! – The Last Birthday Party) only ever got as far as an unofficial DVD-R, put on sale through a fan Birthday Party website, in 2008. However, it does contain a rare glimpse of the force and majesty of Cave in the studio, via an impassioned, guttural vocal performance of ‘Swampland’ in which he spews and expels with such venom and snarl that you half-expect something to climb out from his gut and escape from his throat. It ends with Cave fucking up, tossing his headphones away and exhaling deeply, his palpable degree of frustration and irritation somehow perfectly emblematic of the state of the group itself. Mühlenbrock recalls those sessions as being "intimate" but also recalls a difficult atmosphere due to "tensions within the band paired with drug use".

This session also involved Blixa Bargeld of Einstürzende Neubauten, a group The Birthday Party had befriended during their stint in Berlin, having found them to be – somewhat understandably – kindred spirits. Cave had seen them on a television performance, while on tour in Amsterdam in 1982. "He was the most beautiful man in the world. He stood there in a black leotard and black rubber pants, black rubber boots. Around his neck hung a thoroughly fucked guitar. His skin cleared to his bones, his skull was an utter disaster, scabbed and hacked". He would play on ‘Mutiny In Heaven’ (sadly not caught on film), which would mark a shift even further away from the Cave/Howard partnership, as Cave had not only gravitated towards writing with Mick Harvey more often, but now sought to include Bargeld’s guitar on the record too. In fact, Harvey said in 1984 that Blixa’s presence had helped keep these sessions on track. "He was at the controls while everyone else [was] in states of total depression. Blixa was keeping everything going."

Harvey now recalls Cave’s attitude from that period. "Nick was quoted near the end of the Birthday Party as saying he couldn’t really relate to the music of the Birthday Party, so you’ve got a … nail in the coffin right there." The quote in question is likely taken from an Australian Rolling Stone article from 83, in which Cave’s opinion of the group seemed to have soured enormously, and was a clear indication of his desire to leave the group and move on. "Honestly, I can’t conceive of this band doing this much longer," Cave said. "I’ve said it before that we’re going to break up, but I do believe that if we can put out one record that totally epitomises our group – and that it is the sort of record that you can’t play as background music but has so much presence and is the ultimate statement of the band – then it’s time to break up, and I think that this record will probably be it… I really don’t place that much importance on the Birthday Party. It’s only music, and I think our group is totally dispensable. The sort of music we play is trash music. It’s utter rubbish and for that reason we’re totally dispensable."

Mick Harvey decided to call time on the band. Everyone agreed, but then thoughts of money crept in, and a final tour of Australia was proposed. Harvey refused. "I just couldn’t see the point in going to Australia," he tells me. "There was no challenge to me by going to play there again. Of all the things that could challenge the band and get us playing well and positively and artistically, going to Australia was not going to be one of them. It was just an excuse to visit your mum. Whereas the last thing we did before that was a twenty date US tour, and that was fantastic because it was a real challenge, they were all seeing us fresh, most people for the first time – you could really get that surprise kind of energy going and get an original type of interaction out of them."

Henry Rollins, who had seen them on this US tour ("I stood in front of Rowland to get all that crazy guitar. I have a tape of the show, it was really strong, amazing really") and would go on to spend a lot of time with Cave in 1984, like many, sees this end period as the group’s ultimate, and a fitting – albeit imperfect – ending. "I think Bad Seed and Mutiny! are ultimate records. They are just incredible. I don’t see how you top them. I think the end of the Birthday Party was a good thing, as much as I liked the band, things have to move." Chris Bohn, too, saw this as the perfect material to end on. "I think those two EPs elevated the Birthday Party to a real, extreme point," he says.

The group returned to England and finished Mutiny! in the summer of 1983. Jessamy Calkin – whose friend Lydia Lunch had turned her onto the Birthday Party – had secured the group’s only article in UK style magazine The Face the year before, although she remembers the interview being a nightmare. "It was a painful experience. Nick was late and in a bad mood because he’d just been busted for drugs. It was my first interview for The Face, and my questions were a bit dumb." She would later, during this summer of ’83, become friends with the group. "I was in Brixton one day, where I lived, and I bumped into Anita [Lane, Cave’s then girlfriend] at a charity shop. She was buying a dress for an interview with a landlord; she was trying to rent a flat for her and Nick who was in Australia [on the final Birthday Party tour]. It was an extraordinary set up, that place, a flat in a mock Tudor mansion all built around a courtyard with a swimming pool. Nick used to lurch around the swimming pool in his leather trousers and vest, while all the other residents were barbecuing. I spent a lot of time with them that summer."

Of the final ever sessions the Birthday Party would record at Britannia Row studios, Calkin remembers "Nick leaving the studio mid-morning having been there all night saying ‘I’ve got to go home and feed Anita’ – she didn’t have a key or any money for food and transport, for some reason. There were a lot of drugs and Nick writing spidery lyrics all through the night … I remember Nick writing ‘Cabin Fever’ in Brixton, wriggly writing all over page after page, nodding off. His flat was claustrophobic and slightly menacing, which really suited the song."

Mutiny! would be finished by August, ending the Birthday Party once and for all. By September Nick was contacting people to be part of his new band, with the initial intention of putting out a solo EP on Mute entitled Man Or Myth. Around this period Cave would guest with friends and former tour mates Die Haut at a festival in Rotterdam. Calkin recalls being "all squashed into a cabin on the ferry. We smuggled amphetamines over in our socks."

By late September Cave had put together his band, made up of Cave himself, Mick Harvey, Jim Thirlwell, Barry Adamson and Blixa Bargeld. They entered The Garden Studios to record a few songs that Cave had written, and Flood was brought in to engineer the sessions, "My name had been passed on to Nick via Marc Almond [of Soft Cell, whom Flood had worked with] as somebody who liked that kind of music and is also an engineer at the same time. I got a phone call to go in and see Daniel Miller at Mute, I thought I was going in there to see him about doing Depeche Mode, so it was quite a shock when he said ‘Do you fancy working with Nick?’ and I said, ‘Great.’"

The session was a clear departure from the Birthday Party. The focal point of the first session was ‘Box For Black Paul’ a nine-minute piano-led number, crepuscular in tone and eerie and brooding in presence. The feral ferocity and intensity of the work had gone nowhere, but it had been refined and structured. Gone was the indistinguishable guitar screech of Rowland S. Howard, and in was the indistinguishable guitar hum of Blixa Bargeld. Using his unique methods – odd tunings and seeming dislike for his chosen instrument – he created sporadic winds and puffs of haunting atmosphere. If Rowland’s guitar presence was that of a frayed wire, swinging perilously above a pool of rusty water – instilling a spine-tingling sense of fear and anxiety – then Blixa’s became an icy, silent wind that creeps in through a broken window, whipping up your backbone in the black dead of night. Cave said of Blixa, in a 2014 New York Times interview, that "He’s always approached the guitar with reticence and loathing".

Flood recalls the session. "The Garden had an incredibly live but almost sort of distorted type of sound, so it always made cymbals and guitars sound very harsh when they were recorded. So that pushed everybody into a place that I wasn’t expecting to go." At this stage it was a session without too much direction. "The first Garden studios, it was just putting down a few tracks, I wasn’t sure where it was all going," remembers Adamson. They worked on a few songs from what would eventually become the album From Her To Eternity – ‘Saint Huck’, ‘Wings Off Flies’, ‘A Box For Black Paul’, and an early, hugely different, version of ‘From Her To Eternity’.

Jim Thirlwell’s time working with the group was fairly brief. "Nick and I wrote ‘Wings Off Flies’ together, we actually wrote it at Lydia [Lunch]’s place in London on her piano," he says. "She had the words and he’d worked on the words with this guy from Melbourne, Pierre Voltaire." He would contribute, as did the whole group, to From Her To Eternity, but he would soon depart. "I somehow dropped out of that [project], as I had signed with Some Bizarre and was in the middle of a big recording session, which turned into the album Hole, and all the 12"s I did around that period," he recalls. Mick Harvey, however, also remembers a clash in approach. "Jim’s method of working didn’t really match. He was so used to working by himself and organising things in a studio in a very particular way, and we were used to shambling through it, if you like, so the different methods didn’t really match up so much."

However, Jim and Nick would go on to work together very soon after these brief sessions. "Right around that time Lydia got an offer to play on Hallowe’en of 83 at the Danceteria in New York, and she came up with this proposal to Nick, myself and Marc Almond that we do this thing together as a revue," Thirlwell tells me. She came up with the name The Immaculate Consumptive, which we all liked, the money was good, we all liked the idea of going to New York and doing this thing, we were all friends, we all hung out and stuff."

The revue would last three shows before dissolving. Chris Bohn was present for NME again. "It was one of the greatest things I’ve ever seen," he recalls. "It was fantastic, but it couldn’t sustain. Maybe you could say that about the Birthday Party too."

Thirlwell recalls the set-up: "Nick did ‘In The Ghetto’, I think, and ‘Box For Black Paul’, which he just did with piano and vocals. I did this song that Nick and Barry played on, and at least one Foetus song. Then I think at the end we all did a track where we all played together. It was kind of a revue – we started with a couple of tracks with Lydia, and I played sax with those, and I think I played sax with Marc and then we did a duet or something… I think they were really good, from what I remember, and I think the energy was good, but I was frustrated each time with Nick because he never seemed to finish ‘Box For Black Paul’. He would play it – and it was a long song – for five minutes, and then he’d say ‘Oh, and then it goes on like that for another few verses’, and he’d just walk off. I think he’d never finished it and that always frustrated me. I don’t think we were ever a group; we were just a bunch of people who played some songs and performed on each other’s songs. It wasn’t like we all picked up an instrument and wrote songs together or anything like that."

Jessamy Calkin was present, and recalls it being a tough time. "I sort of tour managed that tour. It was very tricky. Chris Bohn and Anton Corbijn came on some of it too. Chris wrote an excellent article for NME about it; I remember a line that said ‘Nick playing good-natured mongoose to Lydia’s cobra…’ which just about summed up the tension between those two. By then Lydia was involved with Jim. I do remember the performances at Danceteria in New York. Jim’s performance was totally wild, and then Nick came on doing ‘Black Paul’ or ‘In The Ghetto’. There was quite a lot of competition between them, though neither would ever admit it. I can’t remember a lot about that tour; there were a lot of drugs involved. I had to be a go-between, because by then Lydia and Nick had really fallen out."

In December of 83 and January of 84, a new line-up was assembled to play in Australia. Hugo Race, then of Plays With Marionettes, was brought in on guitar (as Blixa was tied up with Neubaten), Barry Adamson moved on to second guitar, and Tracy Pew came back in on bass, with Mick Harvey on drums. Billed as the Man Or Myth tour, it was the first post-Birthday Party tour, and one which Hugo Race remembers fondly. "This was a very wild time. I remember Rowland teaching me the guitar part for ‘Swampland’, which was very tricky to get right because of the time signature. That solo tour was unforgettable. Big, rowdy audiences, and us playing a lot of Birthday Party songs yet not being the Birthday Party – being, in fact, very different in many ways. This drew a lot of derision, and Nick didn’t mind getting nasty with the crowd, but you could see how this was wearing him down. The last shows in Sydney were amazing, [by then] we’d finally intuited how to play together as a band. The band itself was led by Mick’s drumming; when I was getting something wrong he’d give me the death-ray stare. Actually, he’d give us that stare even if it was going right! These weren’t laid-back easy times. The energy was very unpredictable, and there seemed to me to be a vein of violence running through everything."

Tracy Pew subsequently left the group, which led to Adamson moving back onto bass as Bargeld returned as guitarist. The band would temporarily become known as The Cavemen. It would be this line-up that re-entered the studio, this time in Trident, to finish what would become From Her To Eternity. The sessions were long, gruelling and by all accounts madness-inducing. The intensity of this time still has an impact on Jessamy Calkin today. "Endless speed-filled nights with ‘In The Ghetto’ on a never-ending loop. I still can’t listen to that song. That’s where I took the polaroids for the album cover."

It was during these sessions that an album really started to take shape, its structure drawn together. Barry Adamson recalls: "[During] The Garden sessions I’d go there in the evening and then come home in the early hours, having done a few bits and bobs. But by the time we got to Trident you felt like you were in this sort of fully committed thing that was going on, so you’d go in there at two in the afternoon and leave at dawn."

Hugo Race remembers the mindset the group adopted for this new material. "The actual sessions were fairly chaotic; I remember what seemed like a period of days while Nick mastered the piano part for ‘Black Paul’. There was this idea in the air that nothing could be valid if it sounded like anything previously done, which was certainly Blixa’s point of view. The vibe was toward the avant garde – nothing acceptable that might be construed as ‘rock’ music. Blixa’s influence pushed this idea, and the first two Seeds records are really marked by him. I seem to recall singing vocals for ‘Cabin Fever’ inside a large metal box, and at another session working on a guitar part with a damaged jack input that kept giving off very high frequency noise shocks, which everyone thought was great but wasn’t what I’d intended. There was a feeling of attempting to visit new and uncharted territory. It couldn’t sound like the Birthday Party. We had to discover a whole new thing."

Mick Harvey similarly recalls these intentional shifts away from anything Birthday Party-related. "Starting as a band and recording as a band is what we had always done. With this stuff there were long narratives and the music was linear, so it was really quite different to what had been done before. I’ve always thought he [Nick] was trying to follow on from his statement about not being able to relate to the Birthday Party’s music. I think he was trying to find out what music he really was interested in making."

Narcotics were prevalent during the session but, by all accounts, in an unconventionally functional way. "There were always a lot of drugs around, mainly speed and heroin," says Calkin. "It had a lot of influence on their behaviour obviously, and there was a lot of paranoia. I’m sure it had a lot of influence in the studio. There were some very dark scenes, but their creativity was unstoppable and an incredible force. The music speaks for itself."

Flood, a non drug-user, remembers this aspect. "As an overview, the drug use was kept pretty under control. It was just that I’d never been in sessions, a) with that quantity, and b) those type of drugs. There were a couple of occasions where things got extremely hairy, but the way that they worked was that they sort of covered each other. If somebody was coming up with an idea but also coming down, somebody would then come in and sort of engage and finish the idea off. As with all things, if everybody is high as a kite the entire time during the session, then nothing will get done."

Harry Howard, Rowland S. Howard’s brother and formerly a temporary touring member of The Birthday Party (covering one of Pew’s absences), also saw a working functionality to their use. "The fact that their creations seemed to become more and more focused contradicts the idea of drugs fucking them up." In many ways, for some they were simply a means of staying awake, as Adamson tells me. "You found yourself in this situation where you were basically tied to the tracks, so you’d do whatever you could to get through those sessions – and they were long."

"The hours we kept were absolutely ridiculous," confirms Flood. "There was most definitely sleeping under the piano cover on quite a few occasions."

This fusion of new minds and ideas proved, as you might expect from looking at the personnel on board, to be incredibly creatively fruitful. Barry Adamson also credits this to Flood’s presence. "Flood was bringing this other thing to the table, he became this really stalwart bloke who was taking all kinds of shit, but could fucking cut a two-inch tape in half and glue it back together from multi-takes and then come up with something that was absolutely genius. He worked the desk in a way that brought out another element to what was going on, as well. I mean, don’t forget, this was trying to find stuff that had not been heard before, that was original. I remember him as a seventeen year-old making the tea at Trident when I was there with Magazine, but the boy had definitely become a man."

Recalling some of the moments that were sparked in the studio, Adamson continues that "I think in those situations, things go to another place that’s beyond definition. There are elements that are pulling and pushing and causing a sort of creativity within that. I think that’s what happened. I think if you put highly creative people in a room together like that, from very different backgrounds, it’s like, light the blue touch paper and then retire. All these sparks seem to fly, and be they fraught or harmonious, there’s great stuff happening."

Mick Harvey recalls the exploratory and experimental nature of the sessions with a rather wonderful anecdote. "I famously came back after a whole night’s sleep, and I came in and Blixa was there, still in the studio. He’d been in there all night and he was still doing the same guitar overdub. But in fact what he was actually doing, after eight hours, was tuning. He had been tuning his guitar all night. So, you can start to understand the condition we were in."

Flood recalls having to reel the group in at one stage. "One thing I am really glad never happened was that they were trying to get the sound of a piano being destroyed, I think it was on ‘Well of Misery’. Somebody had a saw and was trying to saw the piano strings, and I had to run down and just go ‘Guys, really, you could risk getting this wrapped around your neck and then death is possible.’"

The title song, ‘From Her To Eternity’, is a wonderfully wonky yet intensely climatic song with a strange, jilted rhythm running through it like a piano crashing down the stairs, with basslines that patter like a killer’s footsteps creeping up behind their victim, and with strange, nightmarish guitar tones that sound like mangled, buckling metal as frequently as they do buzzing insects crawling around in your ears – all cemented by an impassioned gargle-to-croon vocal from Cave. It’s an album standout, and in 2014 it’s still in the Bad Seeds’ live repertoire. It’s also the only song on From Her To Eternity to be credited to every member, yet specific memories of its recording are scattered at best from some, and entirely vacant from others. The recordings took place over both sessions and changed greatly in tone, pace and structure, making it something of a Frankenstein’s monster of a song. It is also, as a result of this, deeply symbolic of the group’s then-embryonic state, yet also of their growing and solidifying as a unit.

The entire session culminated with an immensely intense capturing and mixing of ‘Cabin Fever’, as Flood recalls, with almost equal glee and horror. "For many, many, many other reasons that I can’t go into, the sound of the stick clicks on ‘Cabin Fever’ – that is a really poignant overdub, and if there was ever a track that was more aptly named, then it’s ‘Cabin Fever’. I will say no more."

Mick Harvey reflects that "He [Flood] was stuck in there for huge chunks of time, not getting much sleep. He was on the edge of paranoia, too. We finally finished the mix for ‘Cabin Fever’ at seven in the morning, when the album was meant to be delivered that day, we worked through the night and finished the mix. We walked out of there at seven am completely insane, out of our heads, and that was it."

It was these sessions that laid the foundations for what would become Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds, although it was not for another month that they would go under that name. They played a few more shows as Nick Cave and the Cavemen, before, on April 21st 1984 in Amsterdam, they were billed as Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds. They would then revert briefly back to the Cavemen before becoming permanent Bad Seeds.

Henry Rollins was with the group around this time, and watched them in Bristol when Black Flag had a day off from their UK tour. He recalls the shift that had taken place. "I thought the mood was more brooding and revelatory, without the cynicism of the Birthday Party, without the onstage antagonistic brutality. It seemed to me that Nick and company were really trying to do something new. There was an earnest ambition that I think has become Nick’s story, ultimately." Rollins and Cave would become good pals, spending time together in LA later that year. Cave once recalled the experience to the Independent in 1997. "He used to come around the house and do push-ups on our living-room floor, much to our delight. I’d be banging up speedballs while he was doing press-ups in the same room."

The Birthday Party had been gone for less than a year, and many people expected the Bad Seeds to continue where they left off. Hugo Race remembers playing the album live for the first time. "The From Her To Eternity world tour drew crowds expecting the confrontationalism of the Birthday Party, so in fact we had the same audience expectation, yet we were a very different band with a very different repertoire – quite a lot of downbeat tracks, every concert started with ‘Black Paul’ as a kind of provocation, this very long, quiet song with people yelling and throwing stuff from the audience. Things were still very wild on every level, and I think we were all kind of sick of it. I remember blood on the monitors at the stage’s edge."

Jessamy Calkin would tour manage the band as they took the material on the road in the US. "I was totally disorganised, but I think they thought it was quite funny. I used to keep the money gaffer taped to my leg inside my cowboy boot, rather than in a briefcase. It was drug-fuelled, chaotic, bad-tempered, shambolic, intense, but some of the shows were extraordinary. The difficult part for me was the transition from being their friend to being their tour manager. Nick became a total asshole during the tour, and a couple of them were always trying to wheedle money out of me for drugs. Hugo used to pretend I hadn’t given him his per diem allowance, which was about $15 a day, in order to get more. Once Mick Harvey thumped him for me – that was enjoyable. There was a lot of bad stuff going down between Nick and Barry, drug-fuelled fights. At the end of the tour we all split the profit. I think the band made about $400 each. I had lost Nick’s air ticket and had to buy him a new one, so that ate up my share."

From this recollection you’d think that a Birthday Party-like inevitable implosion was lurking only moments away. Instead, this year marks the thirtieth anniversary of From Her To Eternity, a celebratory milestone of the one and only Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds.