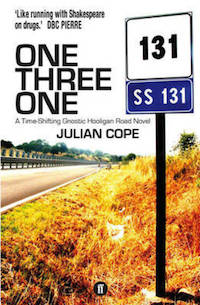

Photograph courtesy of Antronhy

When asked about the complexity of his first novel, V, Thomas Pynchon famously replied ‘Why should things be easy to understand?’ Julian Cope, it seems, has adopted this motto at maximum volume for his own fiction debut. In the midst of all the drug taking, time travel, and revenge plots, perhaps most confusing is Cope’s choice of subject matter: while we all know that in appreciating a work of fiction, it’s a mistake to look for too much of the real life behind an author’s characters, as if the novelist has simply transposed himself into a parallel universe, on the other hand, every writer worth their salt should be aware of the folly in dismissing the notion that there’s much of oneself in one’s own work. But to have the Archdrude come blazing out with a Football Hooligan Road Novel from the Rave Days? “Baffling” barely begins to describe it. Main character Rock Section flinging himself between 2006 and 10,000 years in the past via megalithic psychic Doorways makes more sense than this.

You’re going to have to trust Cope. Whatever it was that brought this book into your hands – whether you’re a fan of his music, writing, or both – believe that he will carry you through. Not without many-a-challenge and digression. Not without spending the opening 72 pages scratching your head, asking ‘what the fuck is going on here?’ and ‘why the fuck is Julian Cope writing this?’ But transport you he will, hell, transport is one of the main themes of the novel. No mistake, it’s a full-throttle trip from the get-go. But for that first sixth of the way, you’re being driven blind on a joyride gone berserk.

It couldn’t be any other way, really. Ageing rockstar Rock Section is the one telling the story, his qualifications ratified on the very first page as he literally shits his leather trousers in an airplane lavatory, off his face on a ‘smorgasbord of illegal, psychiatric, and over-the-counter drugs’. But this is a road novel after all and, as Rock stretches medicinal ingestion to the point of multiple millennial hopping, Transcendence rolls into play. Rock lays out the majority of the facts – his reasons for returning to Sardinia – from the beginning: he’s here to sort out the events of sixteen years previous, when – along with his friend Mick Goodby and his two young nephews – Rock was kidnapped and tortured at the hands of Dutch fanatic Judge Barry Hertzog during the 1990 Italia World Cup. But it’s only much later, as each episode is further and further elaborated upon, that we begin to grasp what’s happening; the monumental importance of Section’s self-proclaimed death mission.

Rock’s been gobbling pseudoephedrine Sudafed since he’s landed but once he stumbles upon his first Doorway and his ‘face suddenly a clockwise propeller’ forces him through to 10,000 years ago (yep), he’s in for a much purer fix. Confused yet? Well he’s about to sort that all out. For in his new but past but simultaneous incarnation, Prince Bjond of Ashop, he presides over a kingdom whose vast fields are full of ephedra. All the subjects live on it, devouring ephedra paste and patties as often as possible, food itself considered suspect. This is speed pure and simple, of the type beloved by students staying up all night cramming for exams. Rock’s not gonna sleep much his three days on Sardinia. But it’s due to this first amped-up archaic excursion that the tale becomes much clearer, this initial megahit greatly focusing his mind. And the narrative gains more and more coherency as Rock repeatedly rejuvenates through further Doorways, even as this brings Prince Bjond’s own cryptic story into play.

With this greater clarity also comes greater fun. Cope doesn’t let up with the amusing names, in fact, it’s downright impressive how much he’s put into the humour. There’s puns aplenty per page. The posh Leander Pitt-Rivers Baring-Gould joins the Kit Kat Rappers under the alias Full English Breakfast, there’s the mobile dance club Slag Van Blowdriver (luckily explained in the text to be a play on an obscure Boer battle), and the ‘Australian Morrissey’ is christened Bruce Easily, to name but a few. What turns the key in the ignition for everything back in 1990 is Mick Goodby, ‘The Bard’, forming Brits Abroad and finding himself with the chart-topping hits ‘Last Tango In Paris’ (based on his fizzy drinks addiction) and ‘100 Watt The Funk’. And then – at the turning point where one really starts to be swept away by the novel – there’s the hilarious scene at The Decoffinated Café, a funeral-parlour-cum-bistro run by the Czywczynsky sisters, Memorial and Buriel. This is very funny stuff, though just part of the author’s arsenal. As one would expect from Cope, more serious issues ride alongside.

One Three One is a novel of great social importance told through the eyes of an ephedra’d-out rock star on a deathtrip, but of course sometimes this is exactly the vehicle such a message arrives in the world through. Vehicles too play a significant role in the narrative: Rock, who as you can guess is never in a fit state to drive, is chauffeured around the island by the captivating Anna in a variety of symbolic cars – a 60s Buick convertible and Facel Vega HK500 with links to Jayne Mansfield and Albert Camus respectively, a hearse as we approach the denouement… all carrying us to Judge Barry Hertzog, leader of the right wing Party Orange (an organisation heavily steeped in C.S. Lewis’ Mere Christianity), and all the bad shit his misguided followers still perpetrate. Hertzog has been imprisoned since 1995 for his heinous crimes and Rock’s first objective is to visit the Judge in his Sardinian jail. We will hear again and again about that fateful day of the kidnappings when Hertzog was perched ‘on top of the RAI-TV tower, playing bagpipes in Rave-orange face paint whilst marshalling his insane Party Orange members far below with a loudhailer’. The British contingent of the Italia ’90 attendees have just lived through Hillsborough and it is a particularly moving section of the book that places these so-called hooligans right in the midst of that whole disaster. Rock Section himself, hailing from Nottingham, observing from the Forest stands, whilst Stu and Gary Have-a-laugh are right in the crush. Cope does mood very well, showing up the utter ridiculous of nearly everyone’s own egoistic trips, but also gives full weight to how a different type of ridiculousness – that of those in power who fail in their one given duty to be concerned with the welfare and protection of their public – deeply affects everyone.

And so we get to the crux of the novel – social responsibility – wonderfully echoed in Section’s prehistoric incarnation, Bjond. The wordplay continues apace in these distant times as the great prince sets out to discover more of the world around him and learns the ways of the Far Reigners. And in doing so begins to see for the first time the problems within his own kingdom. How his own father, Old Tüpp (the King), has been ‘depleting needlessly Ashop’s homegrown forces, its powers, its riches’. But of course with this knowledge comes a grave responsibility, and the same goes for Rock with all the insight acquired during his mission. Sacrifice becomes necessary and it is no accident that Cope points to, by means of the Armenian Reverend Jim Featherian, Christianity’s similarities with one of its near antedecents, Mithraism. Bjond, Mithra, Christ, Rock Section – is this Eternal Recurrence here? Does redemption always require immolation at the height of one’s powers, the truest form of sacrifice? And will the world just return again to sorrier states as doctrine distorts down the years?

There is much talk (given as dialogue) of religion in One Three One, most of all showing up Party Orange’s hypocritical hardline Christianity. Judge Barry Hertzog’s militant followers commit all sorts of ‘uncompassionate and unchristian’ acts without any concern as to whether such heinousness adheres to their beliefs. Two lines from Anna sum up a lot of what’s wrong with organised religion in general: speaking of Hertzog, she asks his disciples, ‘Why are you so determined to attribute to this football maniac all of your own individualistic ideas? Why do you use him to hide behind your own thoughts?’ Duplicity runs rampant, as it does throughout the modern world, and perhaps has throughout all time. Once great ideas have been perverted though continue to permeate without any meaning. Through his characters, Rock and Bjond, Cope seems to be saying that it might not even be important to remember, but what they stood for was once noble. A further nod to this comes by Rock and Anna eagerly tuning in to right-on Sardinian DJ extraordinaire, Jesu Crussu, on their journeys. Crussu’s disembodied voice even brings their hearse radio back to life for a few moments to deliver the pair’s favourite road movie soundtrack, just when it’s needed most

And let’s not forget about Anna. By two-thirds of the way through, ‘Blessèd’ is appearing in front of her name more often than not (with more words accented thusly throughout – ‘smashèd, ‘wrongèd’, ètc. – showing the grandeur of the quest as it is in Rock’s mind). Cope wonderfully portrays what it’s like to be enchanted by an earthly goddess, complete with cosmic sex scene towards the finale, Anna at the height of her powers summoning the elements to do her bidding. It wouldn’t be a road novel without some magic and Cope conjures it deftly (see also the Pynchon-esque fun of Jim Feather, twin brother to the Reverend above, and his fantastical cloak).

When the end comes, we’ve been given the components all along, but that makes it no less enthralling while it happens. Any befuddlement hanging over from the beginning has long since been left in the dust as we race towards the finish line, not without a certain air of sadness at having to part company with this Righteous Tale. Cope himself is very fond of capitalising words of Importance, and One Three One is a Triumph. Of Words, of Feeling, of Meaning. And don’t forget the Laughs.

One Three One is out now, published by Faber & Faber