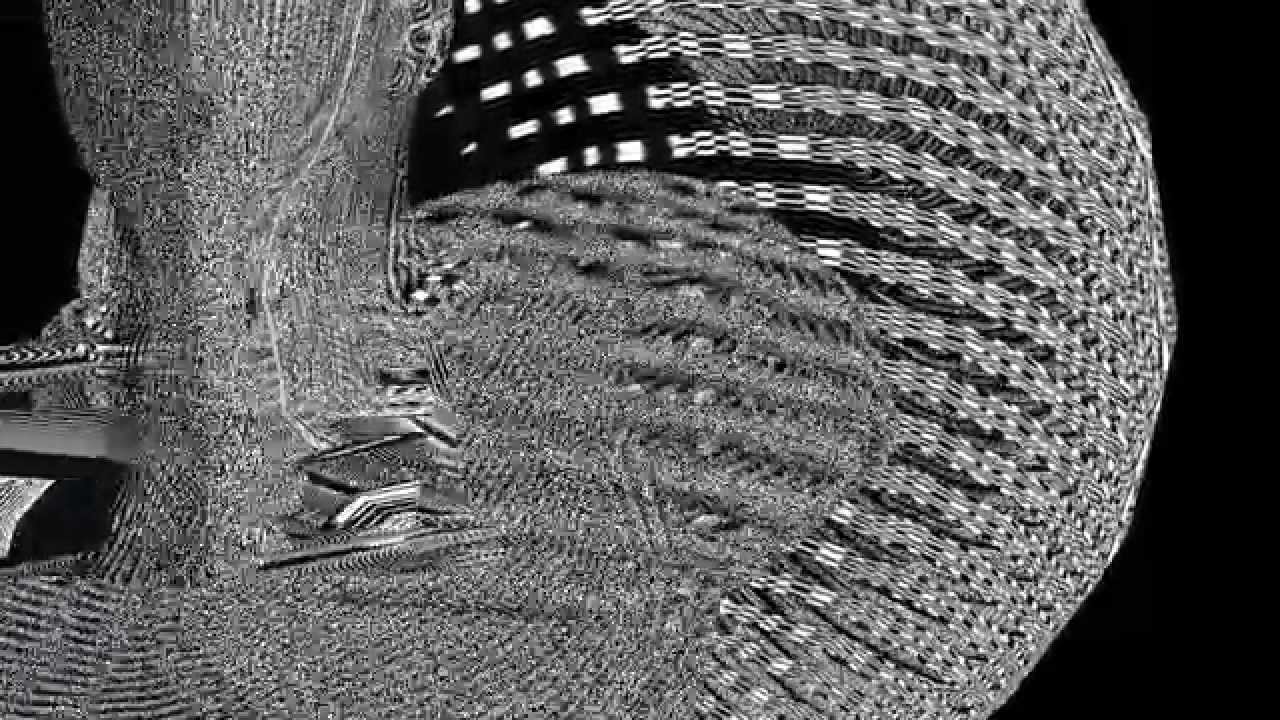

Moiré patterns are new, emergent visual effects that appear when two patterns are overlaid and overlap. Normally considered unwanted artefacts, they give rise to perceptual experiences that are more than the sum of their parts. As a visual effect they’re mostly of interest to graphic designers and artists, but such phenomena appear in music too, and should be familiar to anyone that has ever been taken aback by the bizarre and beguiling interactions that can occur between a handful of elements in a house or techno track. In one musician’s hands, a kick drum, snare, and hi-hat will sound like just those three things placed alongside each other; in another’s they will sound like a unified whole, and something brand new.

With a background in architecture and design, London-based producer Moiré’s attunement to patterns and their effects carries over into music: he’s able to see the wood for the trees, to obsess over the minutiae of individual drum and melody lines while keeping sight of the bigger picture. His immersive, unpredictable takes on house and techno make him a clear ally to fellow Londoner Darren Cunningham, aka Actress, through whose Werkdiscs label he is releasing his debut album Shelter this month.

While he covers similar territory and shares the same eye for detail as his label boss, and admits that restrained and broken dancefloor tunes are nothing new – citing artists such as Theo Parrish and Pepe Bradock as his forerunners – on Shelter his own singular vision of escapist electronic music for the head and body shines through. Speaking to the Quietus ahead of the album’s release, Moiré discusses London, life, and the roots of his nebulous and ruptured take on dance music.

Your first release, the Never Sleep EP, came out on Werkdiscs, quite an impressive label for a debut release. Had you been making music for a while or were the tracks on the EP some of the first you made?

Moiré: I made it probably about half a year before it was sent to Actress, so I had it for a while. Originally that track with Heidi [‘Lose It’] was a different track, that me my friend Lessons were working on. Then we didn’t have time, and nothing was happening. But then I had more time and started making more music, and I finished that – a totally different version of it. We then got together again and finished it, and I did other tracks. My friend, who knew Actress, passed it to him, and he liked it, and that’s basically how it happened. I was always a big fan of Darren and what he was doing, since Hazyville.

I’d been doing music for a long time and never wanted to release; it happened that I was quite lucky, my friend had a little studio that I could use, so I started exploring music and ideas I had which were inspired by other things. It was pretty standard the way it happened, there was no crazy meeting or anything. I just sent a track and Actress liked it, and that was it. Maybe it sounds very easy for me, and maybe it was. The process of releasing is very long – some people say it takes ten years from where you begin to the point where you are ready to release you first track. The principle of exercising yourself, your brain, ears, and ideas, is the most important part of any musical process. That’s my attitude to it at least. I’m not into just turning on some machine and just recording it, I like to actually spend some time working on the composition and the arrangements and everything. I’m sure it was quite a painful process but it seems so simple now.

b>Although broadly speaking the music you make is techno, it’s still quite introspective. Do you have a particular listener in mind when you make the music? Are you thinking about it as music for the club, music for someone at home, or both?

M: There’s a certain spirit that I’m searching for, a certain depth. Some tracks depend on the context and the situation, and why I’ve made it. Some of them will be for the dancefloor, some of them will be for listening to at home. Or maybe people should be listening to them all the time! I don’t know, I never actually think about it, it just happens. Obviously this particular type of music, this particular sound, it has its place in the club, it comes from the club, but a lot of it is actually driving music I’d say. I spend quite a lot of time travelling around, seeing places, visiting people, meeting people, experiencing different types of things, girls or wine or whatever, a good party, after party. A few times I’ll come home after a few days of partying and I’ll make a track out of that. It wouldn’t be about it – just about the feeling, the certain attitude, certain moments, a certain situation. It’s quite complex I guess.

I’ve read elsewhere that you’ve described your music as ‘London techno’; how much has London’s musical landscape influenced you? Is there something distinctive about the way club music from London sounds?

‘London techno’ is my personal term for the way I feel. I’m not trying develop a genre, it’s more about life than actual music. I live in London and that’s what inspires me to make these particular records. London always had that urban landscape, which was quite inspiring. And for some reason a lot of things came from England and from Britain that were important for music globally. I read somewhere that drum & bass was, after punk, the second biggest export from this country. Unfortunately it changed into something else that I’m not into, but when it first came out it was pretty far out. It was kind of another version of techno, twisted – at least for me, some of the sounds and the motifs and the sonics were very deep, and that was something I always loved. When I moved to London I started hanging out with different people and going to d&b nights and listening to this music, [and] although I never wanted to make drum and bass , I like that it was raw and deep, it was like going out to discover a darker side of the city, and rave all night.

I read that you’re not from London. Was there much an underground music culture or clubbing culture where you came from?

M: I never want to talk about it, because actually I never saw it as an important part of my musical life. All of it has been London, Hamburg or Berlin. I have family in Poland and Germany, Italy – one of my granddads came originally from Brazil, although I never met him. But for me it’s not relevant, because I was not doing music when I was there, and the reason I came to England was because of music. Obviously I’m not English – anyone who is English is going to know because of the accent. It’s being here and hanging out with people, some of whom I’m still working with today in London, different labels, meeting different people and working with different artists, that has really inspired me.

Moiré patterns are seen as an unwanted effect, something that comes up unexpectedly, but how much do you embrace that unpredictability? Do you like that you get something you might not have expected to get, or is it something you just try to harness for a particular effect?

M: Both, actually. I can sit down and start composing a track that will be a really stripped concept that I plan from the start; or it will be through experimentation, finding something interesting about the way two or more lines interact, it kind of makes sense. I come from architecture, and the lines are always very important for me, I see them in any type of work. In design work you always use lines, but in music it’s still the same. The score writing, or using automation on a computer, or even just certain EQs – it’s all just lines. For me, the moiré best describes the process I’m going for. One side of it is actually describing the process, and the other one is mentioning that unwanted error which can actually turn into something that you want. So I think that is something important to and characteristic of what I do.

One person I was going to mention is Shackleton, because I know he’s said that he places each individual drum hit or element individually, so things aren’t set totally to a rigid grid, and that becomes a way of creating thick atmospheres that you wouldn’t get if things were perfectly quantised and transparent. Making things off-kilter can create something uniquely enveloping.

M: Yeah that’s the other thing, I always loved jazz music, and back home the first people I was hanging out with at home were actually jazz producers. For me jazz was always quite important – the idea of really loose forms that still hold together because the musicians are incredible and can talk to each other, and I really like that. And with the moiré, yeah, it’s an unwanted effect, but actually there’s a method to it. It can be crazy and doesn’t need to be to a grid as long as it goes back to the head, as happens in jazz, and that’s how everything happens.

I’m not the first person to do that – a lot of people do it, Theo Parrish, Moodymann, Pepe Bradock, Kyle Hall. It’s very uneven and kind of chopped up and fucked up. I really like that it’s a dance track and it’s fucked up, and that the moments that you really want only appear a few times and not all the time. It’s not giving away too much, keeping the feeling and the building of the feeling, and I always loved that. The kind of loose structures I love appear in a lot of African music, and the rhythms are often really weird and not on a grid at all. I hardly have snap on at all, if I go to the final arrangement on Logic or whatever, the snap is off. There was a good example of this – the guy from the label who was sending a track to someone from the album as a promo, he said "No one can find where the ‘one’ is in your tracks", and I’m like "What do you mean? I don’t care, so what." A lot of dance music is very straight – and I don’t mind it, and it’s easier to mix, but that’s not the point. It’s bizarre, I’d rather have people train wrecking and playing crazy tracks that evolve to be dance tracks. The DJ question is a different thing.

Was the album always something you’d planned to do, or was it something Actress asked you to do?

The idea came from me. I didn’t want to just keep releasing 12”s or EPs.I went to Actress and said that I wanted to do an album, and he was up for it. And also I thought it would be perfect for me to have it on Werkdiscs. Because of the connection and because of our relationship, it made sense.

It suits the aesthetic and visual style of the label. There’s quite a consistent visual style with your releases and also with Werkdiscs, none of which seems accidental or like an afterthought.

M: The visual stuff is being developed by me and my mate Disguise. I guess it’s just one of those things where you meet people, like with Werkdiscs, and you just click in terms of what you like stylistically. I think with Darren, we communicate on a visual level but we also like different things. The minimalistic approach of Werkdiscs works with mine, which is a little bit more full-on, and I’m a little bit more into colour I guess. Even though a lot of stuff is black and white there’s some stuff that’s going to be in colour. I guess I’m a bit less minimal than they are, but we are both into certain design aesthetics.

Are there any particular visual influences that come through into the music? There are elements on the album that sound like they could be from a film soundtrack.

I do watch a lot of films. I’m massive on French Nouvelle Vague and actually there is a film, a quite obscure film by Henri-Georges Clouzot called La Prisonnière, and it’s a very weird film about a kinetic artist who does a lot of strange kinetic art and a moiré effect machine appears in one of the scenes. I think Dali was designing the shots in some of the scenes; it’s insane, the colours and the weirdness of it, and I always liked that. All the Nouvelle Vague, such as Godard and Louis Malle, although I’m not massive on Truffaut. I also really like the way the soundtracks were made and who was involved, the way they were recording it. I’m a massive film head; I love documentaries, anything by Herzog. I love also weird German cinema and Polish cinema, there’s some good black and white jazz films from the 60s. [Album track] ‘Rings’ is inspired by soundtrack composed by François de Roubaix, from another French film Le Samouraï, by Jean-Pierre Melville.

The name of the album and some of the track titles suggest an escapist place you can take refuge in.

M: The world is a pretty fucked up place, especially today, and I’m quite aware of what’s going on. I’m into politics, in the sense that I know what’s going on, I’m not totally ignorant. For me, making music, I want people to be able to hide sometimes from this media news nonsense that we are blasted with every day, anywhere you go. It doesn’t even need to be news; at work, anywhere. Generally the world is not what it seems to be, some people live in the dream, but really the reality is very different – you kind of wake up. So for me the kind of idea of escaping from the world is not just escapism, but is about listening for a certain sound, searching for personal answers, allowing you to just switch off from normality. I guess most of the music has that.

Tangentially, one thing I would say about the music is that it’s quite psychedelic. Is it self-consciously quite trippy music? You even have a track called ‘Drugs’…

Yeah in general I do like drugs, I like partying, I like drinking, I like tripping, and I think it’s a good thing. It’s obviously a controversy in today’s society, but everyone can probably relate to it and we all do it. If the experiences are great, they are inspiring. Also the other thing about moiré, and the idea with the effect, is that if you stare at it a little, it kind of fucks you up, it fucks with your eyes and makes you wonder what’s going on there. I really like that about music; I want to be able to go to the club and trip musically. Not just because of drugs and alcohol, but because of the music, because there is something about it that is not only allowing you to dance but has another experience to it, another depth. Like with the moiré effect, all of a sudden you are like, ‘What’s that about?’

A good indicator of how bizarre that experience can be is when you leave a club and are on your way home, and how jarring being in an everyday situation can be.

M: Yeah, it’s very weird because you’re leaving the musical space, the actual shelter, and then you are in an environment where everyone is normal but you. Also, I think there is nothing worse than a dry night – I think having trippy, fucked up parties is the best thing you can have when you go out, the stuff you want to talk with your friends about for days. That’s what I always like, the good times, and I think good times are trippy. There is always something to remember for the rest of your life.

Moire’s Shelter is out next week via Werkdiscs